Recalling the preparation for recording the third Faces album at Olympic Studios in the spring of 1971, drummer Kenney Jones told journalist David Fricke that the first priority was “to decide where to put the bar.”

Recalling the preparation for recording the third Faces album at Olympic Studios in the spring of 1971, drummer Kenney Jones told journalist David Fricke that the first priority was “to decide where to put the bar.”

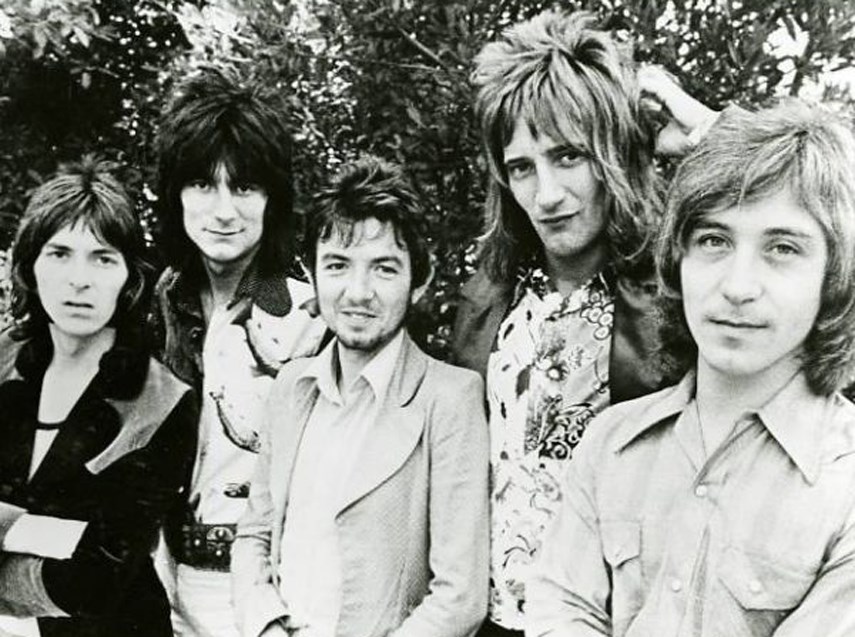

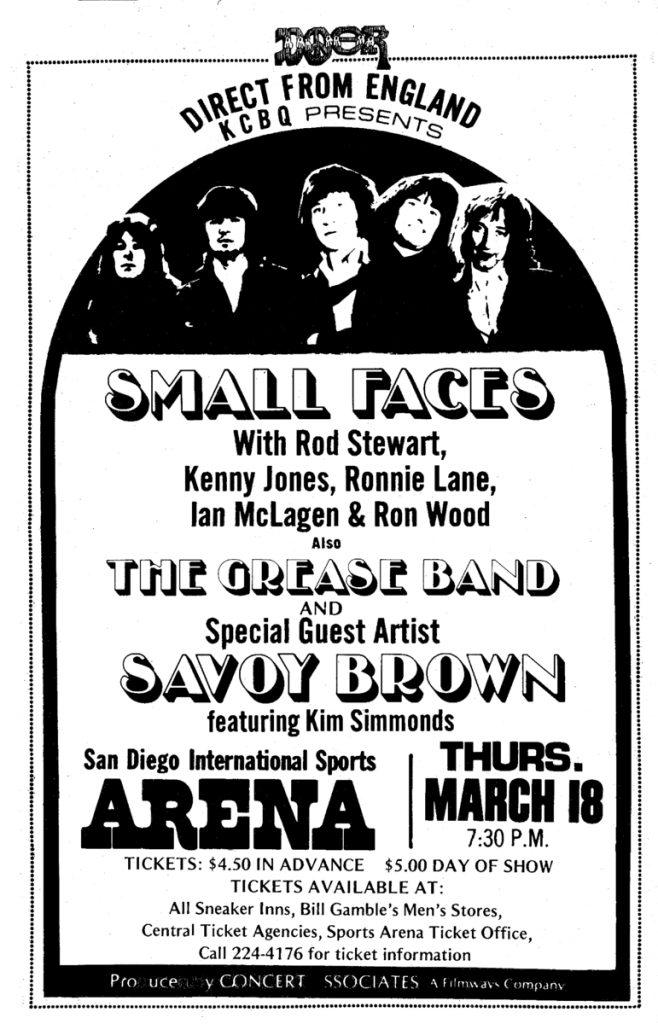

On tour, the group, which included vocalist Rod Stewart, Ian “Mac” McLagan on keyboards, guitarist Ron Wood and Ronnie “Plonk” Lane on bass, had set some kind of new standard for rowdy behavior. “We had a party everywhere we went,” explained Jones. “We’d have a party in the hotel bar, while we were waiting for the limo. We had a party in the limo on the way to the gig. We got backstage and had a party in the dressing room before we went on. We had a party onstage, came off and had another party—in the dressing room, in the car and back at the hotel.”

McLagan confirmed that after taking turns using their own rooms for after-show celebrations, each band member realized it was trashing everybody’s space, so they began booking an extra hotel room in each town, reserved for boozing and shenanigans. Regarding their numerous U.S. and British tours in the early ’70s, Stewart told Fricke, “I don’t remember too many gigs. Still, we were never so drunk we couldn’t play. It was an air of merriment. Under all the camaraderie and joviality, we took the music extremely seriously.”

For his part, the veteran engineer-producer Glyn Johns knew he’d have to rein in the festivities, and get the volatile ego of Rod The Mod under control: “I found him almost impossible to work with, and I disliked him intensely,” he told writer John Tobler. “Although I tried not to let that affect what was going on in the studio.”

The original plan was to produce an album with ballads on one side and rockers on the other, but Faces’ penchant for abandoning a half-finished track and retiring to the pub or studio bar made such designs difficult to execute with the clock ticking before they had to go back on the road. McLagan credited Johns with being the glue that held it all together, and praised his fellow musicians for their extraordinary, often spontaneous musical abilities: “We had no arrangements. On the rockers we just knew what to do.”

Faces publicity photo circa 1971 (l. to r.:) Ian McLagan, Ron Wood, Ronnie Lane, Rod Stewart and Kenney Jones

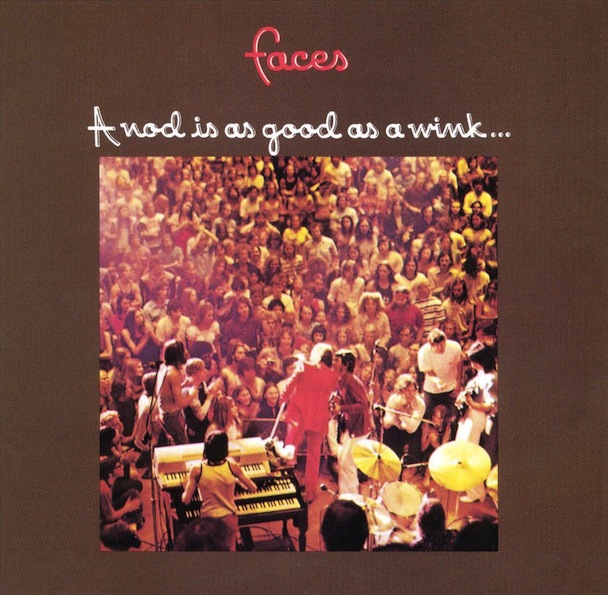

The Faces album eventually called A Nod Is As Good As a Wink. . .To a Blind Horse was a major hit when it was released at the end of November 1971 while Stewart was on tour in the U.S., reaching #6 on the Billboard Top 100 albums chart, and also threw off the perennial radio favorite “Stay With Me” as a single. Few Americans understood the LP title meant something like “a small hint is sufficient to convey meaning to those in the know”: the expression had been around England since the 16th century.

There’s nothing inscrutable about the Stewart-Wood song that opens the set. “Miss Judy’s Farm” starts with Wood’s grungy guitar vamp and Stewart howling like a wolf. Mac’s barrelhouse electric piano and the bashing Lane-Jones rhythm section set in as Stewart seems to pick a random moment to start singing. The pounding one-chord jam allows room for shouted lyrics that combine simple rhymes, poetic license and salacious intent: “Miss Judy, she was moody/Ran a sweaty farm in old Alabam’/I was just eighteen/Crude and mean/All I needed was to get my own way.” The sound is so compelling you barely register how unformed the song itself is; the second half of the track is “just” a series of rhythm changes and call-and-response instrumental tricks with Stewart’s interjections overlaid.

What “Miss Judy’s Farm” conveys is the feeling of absolute joy, of musicians enjoying a creative burst that doesn’t bring a lot of intellectual judgment with it. As an opening salvo, it strongly suggests the album’s theme will be “If it makes you feel good, do it!”

“You’re So Rude” continues in the same vein, this time from the Lane-McLagan writing duo, with Plonk singing lead. It’s a winning mix of Chuck Berry 2/4 time and Lane’s ability to sing a comedic story like he’s sitting in an armchair having a drink with the listener. In this case, it’s about a young man’s plan to seduce his sweetie while his parents are out, with plenty of small details and not much interest in rhyming: “It’s getting dark, we’ll miss the late night bus/It’s only eight but I’m not taking any chances/What’s that noise, why’d they come back so soon?/Straighten your dress, you’re really looking a mess/I’ll wet my socks, pretend we just got caught in the rain.”

According to McLagan, he played a few chords for Lane on a harmonium he had in the hallway of his house, and his mate wrote the rest of “You’re So Rude” in 20 minutes. The multiple keyboards banged so skillfully by McLagan, Wood’s harmonica and Jones’ steady beat sell it all without visible effort.

Wood told Penny Valentine in a 1972 Sounds interview that “there were difficulties” with “Love Lives Here.” “We had four sets of lyrics. Rod gave up and gave it to me to write and sing. I wrote a set of words we were all very pleased with but as we went on we thought, ‘They’re not really right, we’re just saying they are because we’re pressured into finishing the album.’”

As finally recorded with Stewart singing magnificently, the song’s a very poignant ballad that equates a building demolition to the lost relationship that once thrived in the home: “It’s hard to believe that this is the place/Where we were so happy all our lives/Now so empty inside/And feeling no pain/Waiting for a hammer and a big ball and chain.” The slow tempo and interplay of Wood’s guitars and McLagan’s keyboards create a background of considerable emotional ache for Stewart to amplify.

Lane’s “Last Orders Please” sounds heavily influenced by New Orleans’ Fats Domino, with the rhythm turned a little cockeyed and Lane singing it with a big dollop of English music hall bravado. The middle section with Wood’s slide guitar, McLagan’s upright piano and Jones’ explosive snare is just delightful. As with most other tracks on the album, it sounds like a first take, substantially made up on the spot. But maybe the loose feel is an illusion. Talking to Fricke, Stewart acknowledged Lane was the most organized composer in Faces: “Ronnie was the only genuine songwriter among us. He’d come in with a chord sequence and a complete set of words.” Imagine!

“Stay With Me” is built around a rousing chorus and a stereo mix that puts Wood’s slicing slide guitar in one ear and distorted rhythm guitar in the other. “I had the structure of the song,” Wood told Valentine, “but Rod knew where the breakdowns would be, how to shuffle the parts, verse here, the building chorus there, interlude, back to verse.” Wood identified the double-time ending “’til the song burst” as a go-to Faces effect, a barely controlled frenzy that during concerts had the audience truly dancing in the aisles every night.

It contains some characteristic background whooping and impromptu interjections from Stewart, which Johns shrewdly allowed to remain audible in the mix as extra color (“What’s your name again?”). “Stay With Me” has that infectious goodtime feel that flows from every pore in each Faces member. If you need convincing of Lane’s prowess on bass, here’s exhibit #1 that he’s got some serious Motown and Stax in his blood, and Mac is absolutely on fire. Peaking at #17 in Billboard at the time, every year since it sounds more like it should have topped the American charts.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Rod Stewart’s Every Picture Tells a Story

Lane leads off side two of the original vinyl release with one of his best songs, “Debris.” He’s playing the acoustic guitar and fretless bass. Referring to the flea markets that took place in the piles of rubble from the London Blitz that still littered London during Lane’s postwar childhood, “Debris” is directed toward Lane’s truck-driver dad (“There’s more trouble at the depot/With the general workers union”). Lane’s mother had Muscular Sclerosis, the same ailment that eventually struck Lane himself, and he appreciated how hard it was for his dad to raise kids under the circumstances. Two of the most beautiful moments in Faces’ discography come when Lane and Stewart sing the “you was my hero” and “I went there and back” sections together. Wood considers his solo starting at 2:20 to be one of the best he’s ever played.

A relaxed version of Chuck Berry’s “Memphis,” with Wood on pedal steel and electric guitar through a Leslie speaker, and Mac going full Jerry Lee Lewis, is the album’s longest cut. Listen especially to the variety of Jones’ playing and how he and the band keep goosing the tempo.

“Too Bad” was concocted by Stewart and Wood from some personal experiences thrown in a blender with another rowdy, catchy set of basic chords: “Too bad we was thrown downstairs/We never got a chance to sing.” The interlude with Plonk, Mac, Wood and Stewart chorusing is merry as they complain, “All we wanted to do was to socialize/Oh you know it’s a shame/How we always get the blame.”

In some ways, the group saves the best for last with Stewart and Wood’s “That’s All You Need.” Centered around Wood’s astonishingly agile slide guitar, which Johns captures across two subtly echoing channels, and Stewart’s all-out vocalizing, it contains the best lyrics on the record outside of “Debris.” The singer’s describing an odd relationship with his brother: “He went his way/I couldn’t discover mine/I didn’t worry if I ever saw him again/He’s made a profit/While I don’t even own a pocket/And the last I heard/He was sitting at the top of a tree.” When the steel drums by Harry Fowler come in at 4:00, the party jumps up another notch.

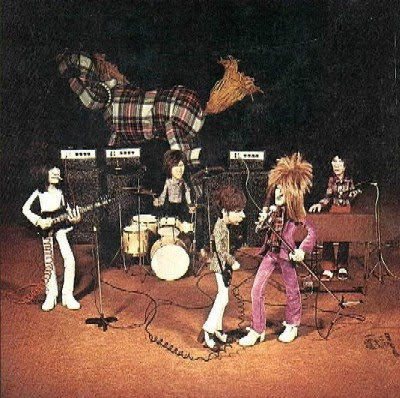

The album’s front cover photo was taken from the lighting rig catwalk high above the Houston Coliseum during a 1971 Faces show, and has been attributed to the band’s official photographer Tom Wright, although it seems it was actually taken by roadie “Chuch” Magee, who didn’t mind the heights when Wright got cold feet. Edwin Belchamber did the amusing Faces dolls shown on the back.

It’s amazing to realize that in 1971 Faces released both their sophomore album Long Player and its followup, while also doing sessions for Rod Stewart’s Every Picture Tells a Story solo record. Would they have created even more good work if they’d been more focused and sober? Don’t bet on it!

[A 9-disc set (8-CDs/1-Blu-ray), Faces At The BBC — Complete BBC Concert & Session Recordings 1970-1973, arrived September 6, 2024, via Rhino. It’s available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Watch Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood perform “Stay With Me” unplugged in 1993

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationStewart was his best in the Faces

good one, mark! i think memphis is THE best cover of chuck’s song. also, i’d like to thank you for adding so much color to one of my favorite albums, and my fave faces album!

There’s a line in the story that says they finished the album while Rod was on tour. Rod only toured with the Faces in those days so they were all on tour. A small point but it’s interesting how much they toured and worked together for a few years. I saw them in Boston with Humble Pie and Doobies who were just making a name for themselves. What a night!