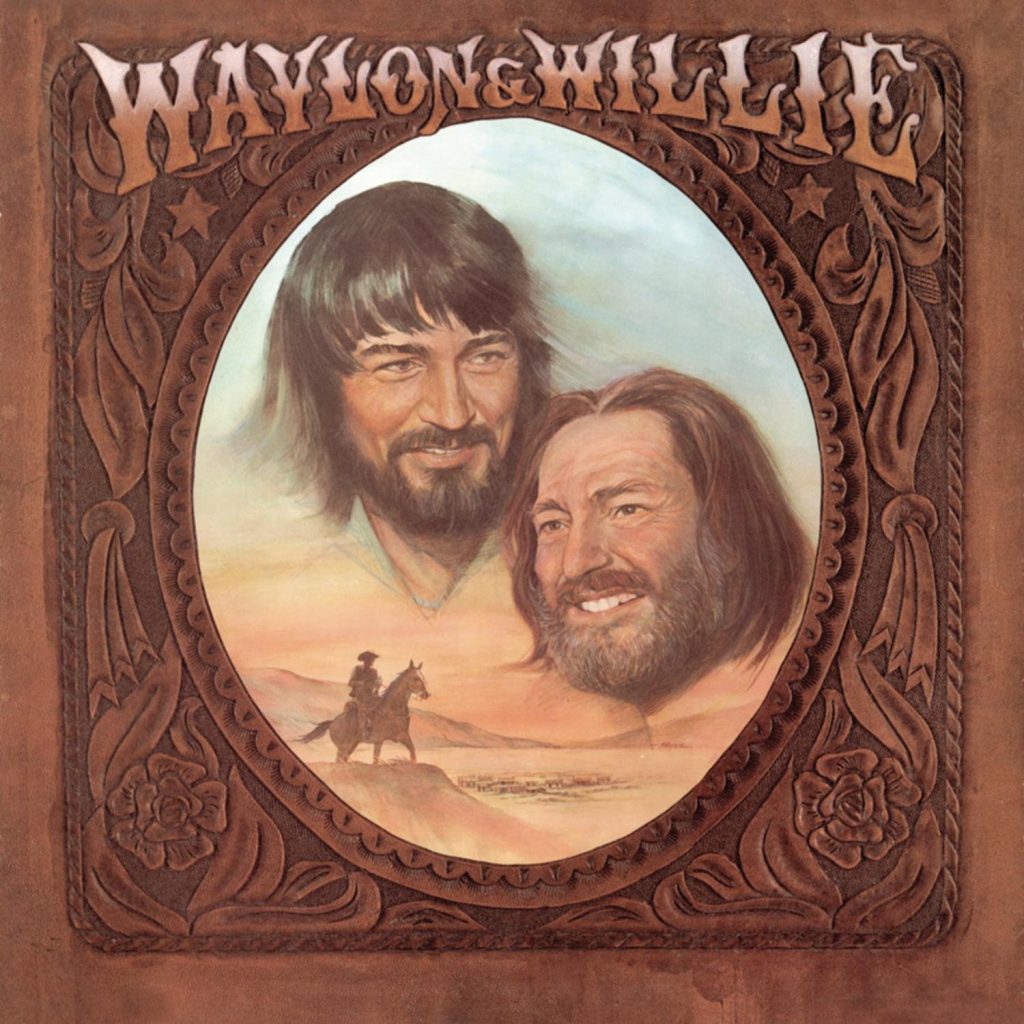

Waylon Jennings & Willie Nelson ‘Waylon & Willie’: Two of a Kind

by Mark Leviton Having achieved three #1 country albums in a row, Waylon Jennings went into 1978 with great musical confidence and (by his count) a $1,500-a-day cocaine habit. In August 1977 he’d been very publicly busted for possession and conspiracy to sell (the DEA raided the recording studio he was using in Nashville—the charges were eventually dropped). His most recent album, Ol’ Waylon, contained his biggest hit single yet, “Luckenback, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love).” He’d been riding the “Outlaw Country” movement for several years without losing his credibility, and America loved him as a consummate performer, songwriter and long-haired bad boy with sex appeal.

Having achieved three #1 country albums in a row, Waylon Jennings went into 1978 with great musical confidence and (by his count) a $1,500-a-day cocaine habit. In August 1977 he’d been very publicly busted for possession and conspiracy to sell (the DEA raided the recording studio he was using in Nashville—the charges were eventually dropped). His most recent album, Ol’ Waylon, contained his biggest hit single yet, “Luckenback, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love).” He’d been riding the “Outlaw Country” movement for several years without losing his credibility, and America loved him as a consummate performer, songwriter and long-haired bad boy with sex appeal.

Jennings’ label RCA was about to release a new collaboration with his buddy (and noted pothead) Willie Nelson titled Waylon & Willie, which was destined to be another #1 country album and stay on the Billboard charts for over two years, getting as high as #12 in the pop music album chart as well. Willie Nelson, after years as a primo songwriter and mediocre-selling recording artist, had finally achieved general country stardom with his Red Headed Stranger album in 1975. He had another LP (his 22nd) in the can, a collection of classic American pop songs called Stardust, which his label Columbia liked not a bit, but was forced to release in April 1978, whereupon it became one of the best-selling albums in history, in any genre.

Watch Willie & Waylon sing “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys” live at Farm Aid in 1986

Jennings and Nelson had already snagged a Grammy for their 1976 duet “Good Hearted Woman,” and reaped the rewards of participating in country’s first platinum album, Wanted! The Outlaws. Due to the pair’s continued notoriety, the new album could be titled Waylon & Willie, last names taken for granted. The January 1978 release was actually a strange hybrid, containing only five actual duets, plus three solo cuts from each singer; new recordings were mixed with previously released and partially re-recorded old tracks.

The original album didn’t list the key Nashville players who contributed, but later some of the couple dozen aces were revealed, including steel guitarists Buddy Emmons and Ralph Mooney, keyboardists Carter Robertson, Dee Moeller and Kyle Lehning, bassists Mike Leech and Sherman Hayes, with Gene Chrisman and Ritchie Albright drumming, and harmonica from Don Brooks. A whole lotta guitarists helped Nelson and Jennings on the strings, including Reggie Young, Larry Whitmore and Gordon Payne.

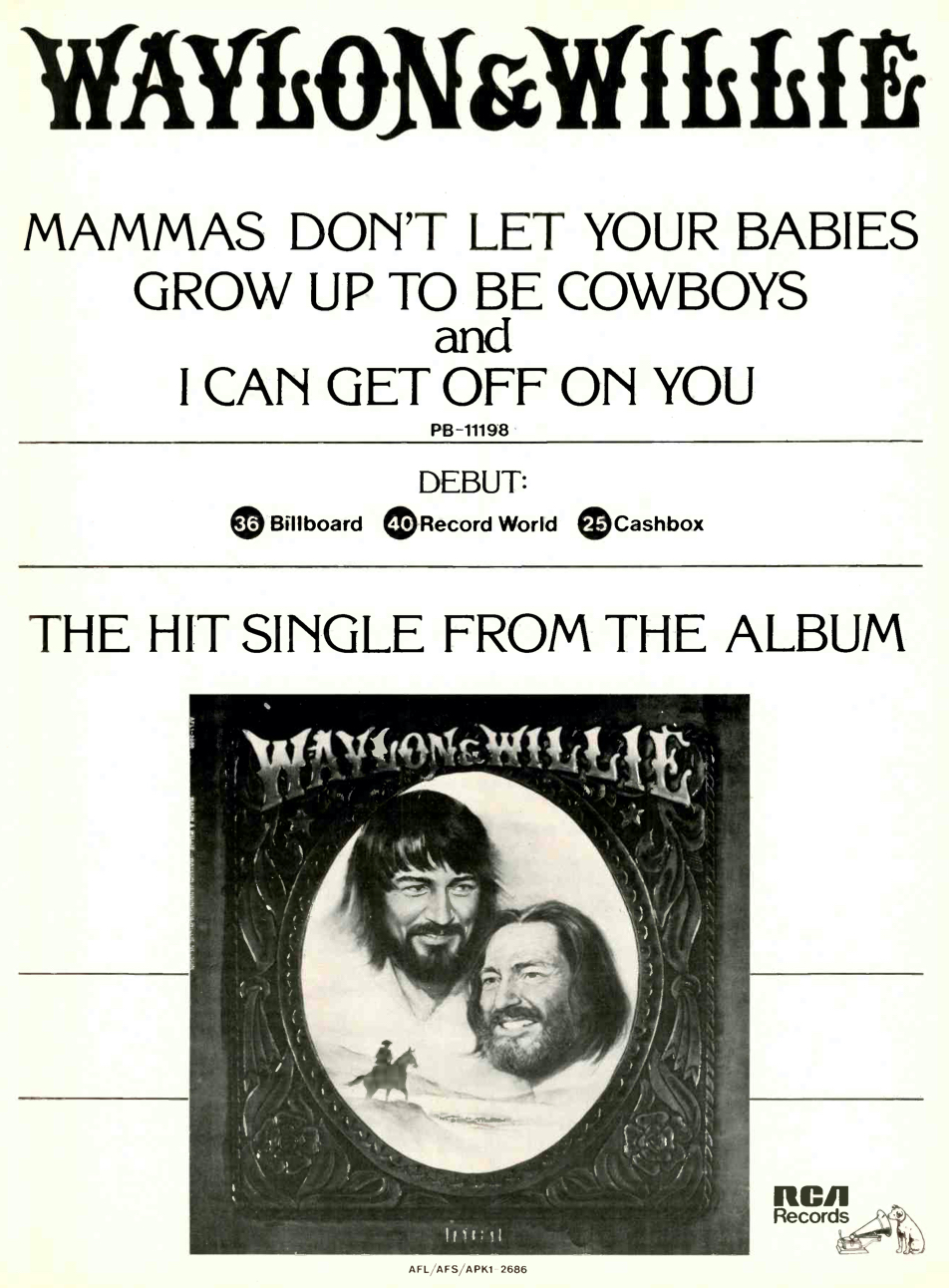

This ad appeared in the Jan. 21, 1978 issue of Record World

Another eventual Grammy winner opens Waylon & Willie, Ed and Patsy Bruce’s rousing and clever “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys”: “Don’t let ’em pick guitars or drive them old trucks/Let ’em be doctors and lawyers and such/Mammas don’t let your babies grow up to be cowboys/’Cause they’ll never stay home and they’re always alone/Even with someone they love.”

Jennings’ smoky baritone leads off, with Nelson’s high. lonesome tenor not far behind, trading back and forth; that’s probably Jennings’ wife Jessi Colter singing background vocal. Released as a single, it went to #1 on the Billboard country chart and peaked at #42 in the pop list.

“The Year 2003 Minus 25” is the first of two Kris Kristofferson songs on the disc. The lyrics are typically tongue-in-cheek (and in several verses definitely not P.C.): “Welcome to 2003 minus 25/Oh say can you smell her for the smoke/God’s still up there laughing so He’s gotta be alive/Who says he can’t take a dirty joke?” The arrangement is excellent, and the singers make it sound like a casual first take. Given what the top-rank Nashville Cats can whip up in the studio, it might have been.

The Nelson original “Pick Up the Tempo” had already appeared as a duet on Jennings’ This Time LP in 1974, but it’s so good it deserves a reprise. The frisky steel guitar by Mooney and thumping bass from Goff are prominent. Nelson sings Lee Clayton’s “If You Can Touch Her at All” in his effortless, heartful style, and over time the lyrics have earned classic status: “Funny a woman can come on so wild and free/Yet insist I don’t watch her undress or watch her watch me.”

The tempo kicks up as Jennings handles his “Lookin’ For a Feeling,” with a Johnny Cash-like vibe in the rhythm, and lyrics about the love that got away. Nelson’s ballad “It’s Not Supposed to Be That Way” ends the first LP side with a peerless performance. Nelson’s light touch is buffered with yearning harmonica lines, a crisp acoustic guitar and keening steel. This is the type of tune Nelson has spun out hundreds of times at this point, and somehow, he keeps them fresh, with undeniable emotional power.

The final two true duets begin side two, the Jennings-Nelson co-write “I Can Get Off on You” and Kristofferson’s “Don’t Cuss the Fiddle.” The first mentions pills, weed, whiskey and cocaine, suggesting they can all be thrown away because the singer can now “get off” on a good woman’s love. It’s a nice sentiment, but plays as wishful thinking rather than commitment. (Despite some rocky times resulting from Jennings’ substance abuse and addiction, Colter stuck with Jennings until his death in 2002, for which she deserves a lot of credit.)

Related: Our Album Rewind of Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger

“Don’t Cuss the Fiddle” is well done, but is certainly second-tier Kristofferson. The melody and rhythm are virtual clones of “Good Hearted Woman,” a similarity acknowledged when they break into it at the end after Kristofferson’s lyrics admit, “I just stole someone’s song.”

Jennings’ version of Stevie Nicks’ “Gold Dust Woman” is quite something. He sings the hell out of it, with some subtle vocal effects: pay attention to how he dips soulfully on “pray” and roughens up “lousy lover” near the beginning. Jennings had previously shown his ability to re-configure pop songs by Marshall Tucker, Neil Young and others, and handling Fleetwood Mac is another triumph. The arrangement is beautiful: listen especially for how the organ and piano parts interweave with electric and steel guitars.

“A Couple More Years” first appeared on Dr. Hook’s 1976 album A Little Bit More, and was the B-side of the title track when released as a single. Written by the group’s Dennis Locorriere and musician/writer/comedian Shel Silverstein, it’s a pleasant enough waltz, and Jennings sounds great doing backgrounds while Nelson handles the chorus, but the Nelson treatment is a bit too laid-back this time.

The disc ends with “The Wurlitzer Prize (I Don’t Want to Get Over You),” written by Buddy Emmons and Memphis legend Chips Moman and sung by Jennings. As a single, it went to #1 on the country chart for several reasons, including its enticing and sentimental retro feel, fantastic double-tracked Jennings vocal, and concise 2:11 length, catnip to AM country stations with tight playlists.

Waylon & Willie often shows up on lists recommending country albums to non-country music lovers; Rolling Stone ranked it #30 on their “50 Country Albums Every Rock Fan Should Own,” calling it a “consistently poignant, pleasingly loopy Number One country smash” and “a last call of circular barroom logic” for the way it moves from world-weary Nelson to “chilling” Jennings performances. The album is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

More triumphs followed for both men, but Jennings was hobbled by his dependence on stimulants and didn’t achieve all he could have in his lifetime. The musician, activist and entrepreneur Willie Nelson, still smoking cannabis every day, has survived drug busts, problems with the Internal Revenue Service and several divorces, and is at this writing still on the road even at the age of 90, now supported by his prodigiously talented children and long-time associates. He’s released just under 100 studio albums, and dozens of live sets, videos and compilations, but he probably stopped counting ages ago. Long may he wave.

Bonus Video: Watch Waylon and Willie perform “I Can Get Off on You” live at Farm Aid in 1986

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.