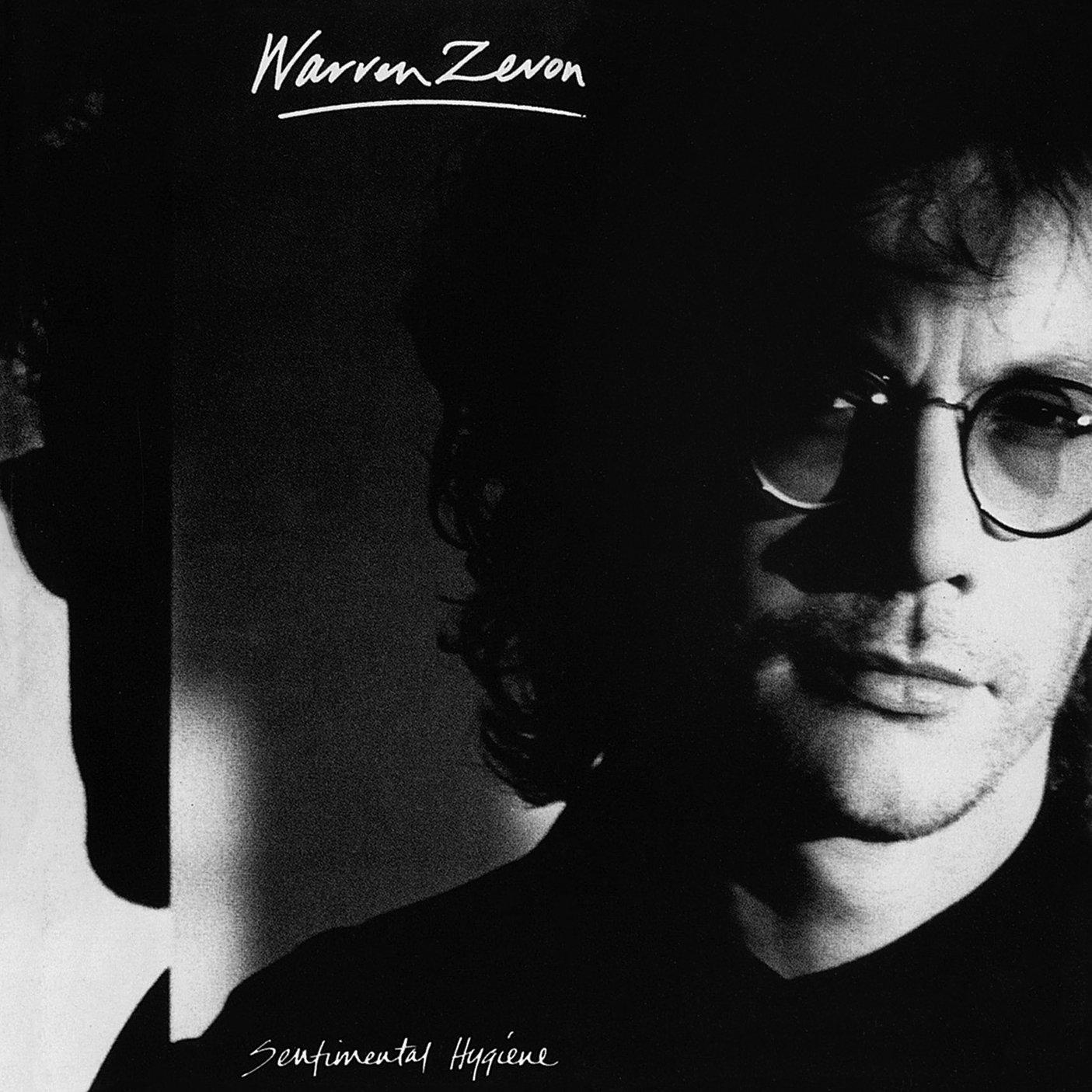

For Warren Zevon, Sentimental Hygiene signaled more than a bid for a career reset. His star had fallen far in the decade since his self-titled 1976 Asylum Records debut album and the commercial triumph for its sequel, Excitable Boy, and its hair-raising single hit, “Werewolves of London.” With Asylum’s first artist and poster boy Jackson Browne as champion and co-producer, those LPs projected Zevon as both ultimate L.A. insider and subversive rock enfant terrible, alternating sophisticated, literate songs with rampaging rockers, backed by a cast of blue-chip musical guests.

For Warren Zevon, Sentimental Hygiene signaled more than a bid for a career reset. His star had fallen far in the decade since his self-titled 1976 Asylum Records debut album and the commercial triumph for its sequel, Excitable Boy, and its hair-raising single hit, “Werewolves of London.” With Asylum’s first artist and poster boy Jackson Browne as champion and co-producer, those LPs projected Zevon as both ultimate L.A. insider and subversive rock enfant terrible, alternating sophisticated, literate songs with rampaging rockers, backed by a cast of blue-chip musical guests.

Performances by assorted Eagles, Beach Boys, Fleetwood Mac members and even an Everly Brother endorsed the Chicago-born Southern Californian as rock aristocrat while his songs veered from conventional pop tropes to spin noir-infused fables of violence, bruised relationships and comic pratfalls. Monsters, psychopaths, and mercenaries shared the grooves with self-absorbed hipsters and wasted libertines, contrasting cinematic vistas with gritty, urban squalor in a City of the Angels with no Tequila Sunrises but plenty of hangovers.

By the early ’80s, however, Zevon’s recording contract and marriage both unraveled. The hard-boiled persona that bragged of “drinking heartbreak motor oil and Bombay gin” was eclipsed by real-life alcoholism. A nightmare rather than dream come true, a published profile depicted the “Crack-Up and Resurrection” marked by an intervention and the first of Zevon’s multiple stays in rehab.

Resurrection was short-lived as his diminished career left Zevon relying on solo club dates and recasting songs as “heavy metal folk,” relying on only his piano or guitar. A new relationship and a move east to Philadelphia isolated him from L.A.’s fast lane, but his struggles with substance abuse continued even as a path back began with a seeming demotion in 1984. Still signed to Eagles manager Irving Azoff’s Front Line Management, Zevon was reassigned to a new manager recently promoted from a lower rung as publicist.

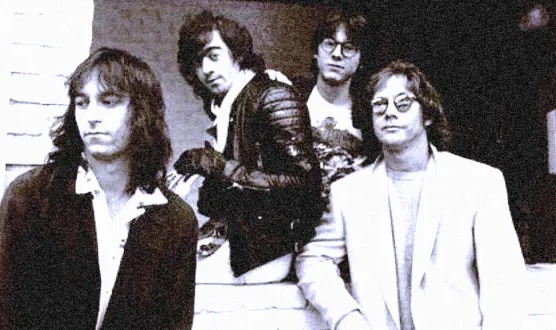

If he was initially skeptical of that recruit, manager Andrew Slater proved an ardent fan and savvy advocate who leveraged a college friendship with Peter Buck, now co-founder and guitarist with R.E.M., to revitalize Zevon. A clutch of club dates in R.E.M.’s Athens, Georgia, stomping grounds found Zevon backed by the rising alternative stars in pseudonymous guise as a band dubbed hindu love gods. The link was further strengthened when Buck, bassist Mike Mills and drummer Bill Berry backed Zevon on demos of new material to court a new contract.

Live dates with R.E.M. members masquerading as hindu love gods helped Zevon reboot his rock mojo. From L: Peter Buck, Bill Berry, Mike Mills and Zevon in a press shot for the 1990 release of tracks cut under that pseudonym during sessions for Zevon’s Sentimental Hygiene three years earlier

Moving back to California, Zevon’s fortunes brightened decisively in March 1986 when he achieved hard-won sobriety that would last for 17 years. Further validation came that autumn with the inclusion of “Werewolves of London” on the soundtrack to Martin Scorsese’s The Color of Money and the release of an Asylum compilation, both landing Zevon back on the album charts. His renewed visibility and strong new material clinched his manager’s pitch to the newly launched Virgin America label.

Watch the video for the title track

A sober and focused Warren Zevon entrusted Andrew Slater to join him in producing the Virgin debut alongside engineer and co-producer Niko Bolas. R.E.M.’s Buck, Mills and Berry served as rhythm section for most of the resulting tracks, with strategic guest appearances from other friends and familiars. The title track opens with a muscular attack in a grim existential anthem of survival that stalks meaning amid the slog of daily life, Zevon’s stoic baritone anchored by dense synthesizer voicings, with Neil Young providing an archetypal solo outlined in blistering single notes.

A positive outcome from Zevon’s ’80s exile to solo club gigs was a renewed focus on guitar, which shaped some of his toughest new material. “Boom Boom Mancini,” written while watching boxer Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini’s bout with Bobby Chacon on HBO, was one of the first songs he’d played with the three R.E.M. members as well as his second foray into lionizing professional athletes. For Zevon, a high school dropout whose high intelligence and autodidact’s curiosity attracted him to literary as well as musical heroes, finding tragic heroism in the ring followed in the footsteps of Norman Mailer as well as Bob Dylan, Miles Davis and Paul Simon, explored here in Mancini’s fate in the unintended death of an opponent in the ring.

Dylan himself appears on “The Factory,” a track that reflects a heightened empathy for working men and women also threaded through the album’s title song. Zevon’s admiration for Dylan would be reciprocated by the latter’s lively cameo on harmonica, continued in Dylan’s concert performances of Zevon’s songs over the years.

Related: Watch Zevon’s final appearance on David Letterman’s show

Among songs that had been road-tested in Zevon’s live gigs between the end of his Asylum career and …Hygiene, his seventh solo set, “Trouble Waiting to Happen” had elicited strong audience reactions among fans familiar with his offstage misadventures as well as the more flamboyant alter egos in his songs. The lyrics are wryly self-referential:

“The mailman brought me the Rolling Stone…

It said I was living at home alone…

I read things I didn’t know I’d done

It sounded like a lot of fun

I guess I’ve been bad or something…”

The song’s comic fatalism is remarkable given its genesis just days after learning he had been dropped by his label. Co-written with erstwhile label mate J.D. Souther, the track features another Asylum alumnus, Don Henley, on vocal harmonies while Stray Cats guitarist Brian Setzer guests on lead.

Zevon follows the shaggy dog complaint of “Trouble Waiting to Happen” with the first and best of the album’s two ballads, written as a confessional plea for reconciliation with his estranged wife, Crystal. All pretense of toughness is abandoned in a vulnerable oath of repentance and emotional devotion, set to one of Zevon’s loveliest melodies and a lissome arrangement featuring Henley’s harmonies, Mike Campbell and Waddy Wachtel on guitars, and Jai Winding and Zevon on keyboards. Pledging “I’ll never make you sad again, ’cause I swear I’ve changed since then,” he vows that “it’ll be alright if we disagree.”

Zevon’s plea was rejected, although his close friendship with his ex-wife and mother of daughter Ariel would endure to the end of his life.

Zevon often mingled memoir with myth to make himself a punchline, a tactic inspired here by an earlier remark by longtime friend Jorge Calderon, who dubbed a fashionable rehab retreat “Detox Mansion.” With his own struggles now public record, Zevon lampoons celebrity recovery on a walking tour set to a hard, syncopated attack by drummer Berry and David Lindley’s slashing lap steel as the singer brags of “rakin’ leaves with Liza, me and Liz clean up the yard.”

R.E.M.’s role is most explicit on “Bad Karma,” with Michael Stipe joining his bandmates as backing vocalist on a hard luck complaint decorated with sitar arabesques. Buck, Mills, and Berry share songwriting credits on “Even a Dog Can Shake Hands,” in which Zevon’s alter ego is a rock star besieged by hangers-on while he’s “trying to survive up on Mulholland Drive,” bombarded by “all the worms and the gnomes…having lunch at Le Dome,” then a Sunset Strip destination for the glitterati.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Zevon’s Excitable Boy

A penchant for stories set against 20th century geopolitics that yielded earlier Zevon originals returns on the album’s strangest track, “Leave My Monkey Alone,” alluding to the 1950s’ Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya. Swahili lyrics, a mix of funk and dance rhythms, and the involvement of P-Funk overlord George Clinton and Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist Flea range far beyond Zevon’s Tinseltown locales.

Released on August 29, 1987, Sentimental Hygiene was supported with a major campaign, with a music video, tour dates and the album budget all confirming his new label’s commitment. Critical reception greeted the set as his strongest since Excitable Boy, but the album reach just #63. Zevon would record subsequent albums for Giant and Artemis before passing away on September 7, 2003, after a struggle with mesothelioma.

Bonus Audio: Listen to hindu love gods perform “Vigilante Man”

The album, and other Zevon recordings, are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationSobriety is generally hard-won.

Yowza! Great article and dive into this somewhat underappreciated Zevon disc. The guest list tell you all you need to know.

Didn’t know that Warren had lived such a hard life. So sad!