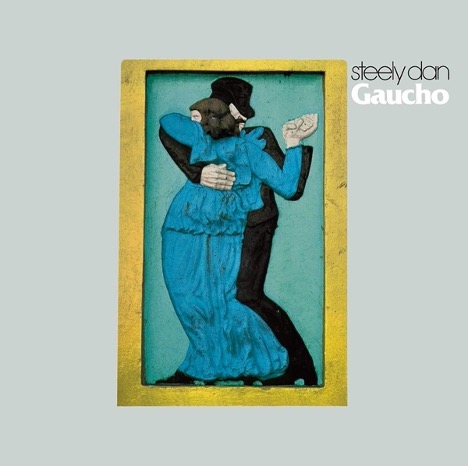

When Gaucho finally surfaced in 1980, any fears that Steely Dan might relax their exacting standards were silenced with the first needle drop. Perfectionist obsessions that had driven songwriters Walter Becker and Donald Fagen remained audible in the sheen of the set’s seven songs. If anything, the arrangements were even more meticulously groomed, their sonic finish smoother yet than on Aja, the acknowledged masterpiece that preceded it three years earlier.

When Gaucho finally surfaced in 1980, any fears that Steely Dan might relax their exacting standards were silenced with the first needle drop. Perfectionist obsessions that had driven songwriters Walter Becker and Donald Fagen remained audible in the sheen of the set’s seven songs. If anything, the arrangements were even more meticulously groomed, their sonic finish smoother yet than on Aja, the acknowledged masterpiece that preceded it three years earlier.

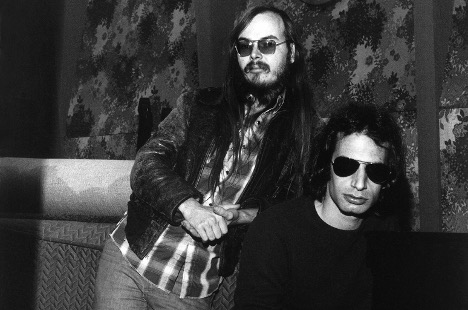

Before Aja elevated them to multi-platinum stature, Becker and Fagen had pushed each new LP further toward ambitious musical and technical goals. Since downsizing from working band to floating studio workshop, they cast an ever-widening net to recruit heavyweight musicians, earning a reputation as demanding taskmasters willing to burn through miles of multitrack tape in pursuit of the perfect take. From the outset they aspired to the state of the recording art, long before Aja became ubiquitous as a demo disc for high-end stereo salons.

Gaucho continued the mission that Becker, Fagen, producer Gary Katz and engineer Roger Nichols began with Steely Dan’s 1972 debut album, but completion required navigating a maze of technical, legal and personal obstacles after the songwriters moved back to New York following six years in Los Angeles. Lawsuits, false starts, lost master tapes, a debilitating injury and an overdose death stretched the interval between Aja and Gaucho to three years.

In all, they recorded a dozen songs during sessions at studios in New York, Los Angeles and Philadelphia, comparable to prior albums, drawing from a pool of 42 musicians. On the eve of its release, Becker and Fagen noted a greater reliance on layering tracks. One casualty of the overdubbing process resulted from an assistant engineer’s accidental erasure of nearly three weeks’ work on “The Second Arrangement,” an early contender for one of their most promising tracks.

Other technical hurdles included tests of the Soundstream system, one of the first digital audio recorders. Ultimately, they chose to stick with analog tape after deeming the sound “different but not necessarily better,” in Becker’s estimation.

Then there was Wendel, a costly adventure to mate the complexity and nuanced touch of world-class drummers with the mechanical precision of disco. Roger Nichols volunteered to tackle the challenge, drawing from his earlier career as a nuclear engineer. Six weeks and $150,000 later, Nichols delivered a 12-bit digital editor enabling them to manipulate and tame dozens of takes into a final rhythm track.

That quest for the perfect groove proved a key denominator across the album, which retreats from bolder shifts in meter to tilt toward steady R&B, Latin and, yes, even muted disco pulses.

The finished album dovetails seamlessly with Aja’s bespoke arrangements. That album had proven a tipping point in Becker and Fagen’s overall ensemble design, stepping further away from rock instrumentation to sculpt the material with keyboards, percussion and horns. Gaucho upholds that elegant restraint with “Babylon Sisters,” a laid-back ode to Cali decadence that kicks off the set with studied nonchalance.

“Drive west on Sunset to the sea,” Fagen directs his companions in anticipation of a three-way tryst set to a faintly anesthetized reggae pulse, undercutting the singer’s salacious come-on to the “sisters.” “This is no one-night stand, it’s a real occasion,” he insists, only to compare their rendezvous to “a weekend in TJ…it’s cheap but it’s not free” before female vocalists offer a soothing refrain that’s a thinly disguised warning: “Here come those Santa Ana winds again,” they coo, alluding to “devil winds” that blow west from the California deserts that Raymond Chandler and Joan Didion notoriously invoked as harbingers of chaos.

The track introduces an undercurrent of sexual anxiety that carries over to “Hey Nineteen,” which leavens its fear of aging into a farcical generation gap between a would-be Lothario and a rollerblading nymph. Ultimately, only sex and chemicals—“the Cuervo Gold, the fine Colombian”—afford common ground.

Southern California dominates Gaucho’s imagery more than on prior albums, its sunlit music contrasted by pitch-black themes of dissolution and decay. Becker and Fagen’s spin on Hollywood Babylon informs five of the seven tracks where prior albums ranged freely between the coasts and beyond, crossing oceans and even venturing off-world.

“Glamour Profession” follows a coke dealer with “the L.A. concession,” connecting with well-heeled clients including an NBA star “outside the stadium” and a rich sybarite on his yacht en route to Barbados, later cutting a deal with a supplier, Jive Miguel, over “Szechuan dumplings at Mr. Chow’s” in Beverly Hills. The track canters at an appropriately accelerated pace, decorated with creamy background vocals and the tenor saxophones of Tom Scott and Michael Brecker.

At the album’s midpoint, the title song downshifts to a gospel-tinged strut framed by acoustic and electric keyboards, bass and Tom Scott’s soulful tenor as the narrator chides a gay friend over his embarrassing crush. The lyrics’ second person focus obscures as much as it reveals, with the chorus wrapping camp imagery in a rhapsodic melody, asking, “Who is the gaucho, amigo? Why is he standing in your spangled yellow poncho and your elevator shoes?”

What might have been misconstrued as a gag line before the AIDS epidemic a year away outs the singer, not the friend or his “bodacious cowboy,” for the narrator’s homophobic scorn.

The song may indict its narrator, but virtuoso composer and pianist Keith Jarrett indicted Becker and Fagen over its resemblance to his 1974 piece, “Long as You Know You’re Living Yours,” a piece the songwriters acknowledged they knew and loved. Following Jarrett’s lawsuit, he was added to the songwriting credits and received a share of the publishing royalties.

Where “Glamour Profession” offered false romance to the cocaine trade, “Time Out of Mind” talks smack, cloaked by a cover promise of “perfection and grace” in lyrics that tease mystical transformations on the way to a fix “tonight when I chase the dragon.” Likewise, the arrangement rides a buoyant groove punctuated by a taut horn section featuring David Sanborn, Ronnie Cuber and the Brecker brothers, with equally bold-faced backing vocals from Michael McDonald, Patti Austin and Valerie Simpson. Mark Knopfler’s sinuous Stratocaster solos are whittled down to 40 seconds of playing time.

Tucked within its breezy delivery is one of the album’s darkest jokes, conflating religious ecstasy with narcotic oblivion and sheathing the proposition in false exuberance. Far from the first time the duo alluded to hard drugs, “Time Out of Mind” was conceived as Walter Becker’s own struggle with addiction was compounded in January 1980 by the death of his longtime partner, Karen Stanley, from an overdose in their apartment.

Related: Looking back at Walter Becker’s final concert

Even as he reeled from that tragedy, Becker was struck by a taxi while crossing a Manhattan street, shattering his right leg in multiple places. Legal and medical crises would largely sideline him from the mixing and mastering phases of Gaucho’s production, which handicapped the completion of the project. Becker, Fagen, producer Katz and engineer Nichols all had keen ears, but Becker had been an alpha audiophile whose input was vital. His absence weighed heavily on Fagen during mixdown and Katz during mastering.

Becker and Fagen’s fondness for oblique lyrics and fractured narratives is on display for the album’s closer, “Third World Man,” a minor-keyed lament for a surreal protagonist in his “bunker made of sand,” who may or may not be a psychopath, given flickering images of fireworks and screaming neighbors. In tone and pace, the arrangement is a lush dirge explored by another all-star ensemble, this time including Joe Sample and Rob Mounsey on keyboards, Larry Carlton and Steve Khan on guitars, and a redoubtable rhythm section in bassist Chuck Rainey and drummer Steve Gadd.

During the long march to complete the album, legal turmoil surfaced, pinning Steely Dan between Warner Bros. Records, to which they had signed while recording Aja, and MCA Records, which had absorbed ABC. Team Dan sought to void any remaining obligation under an exit clause in their old deal, but MCA prevailed. During the interval since Aja, the pop landscape had shifted with the mainstreaming of disco and the insurgency of punk and new wave, with Steely Dan’s mega-budget studio confections prone to a critical side-eye from rock pundits suspicious of studio polish in an age of DIY “authenticity.”

Related: Our Album Rewind of Aja

Commercially, Gaucho, released on Nov. 21, 1980, would reap platinum and crack the top 10 on the album charts, even if it fell short of the preceding album’s impact, earning three Grammy nominations, winning for best-engineered pop recordings as Aja had three years earlier. By then, Walter Becker and Donald Fagen had quietly dissolved Steely Dan, with Becker retreating to Maui where he would focus on recovery while Fagen began working on his solo debut album, The Nightfly, which would appear in 1982.

If their formal partnership was retired, the friendship remained. Gary Katz hosted a casual reunion when they both played on a session for singer Rosie Vela in 1986, prefiguring the welcome surprise of Steely Dan’s resurrection for a live tour in 1993. That year saw Becker producing Fagen’s second solo album, Kamakiriad, with Fagen returning the favor a year later as co-producer of Becker’s first solo set, 11 Tracks of Whack.

Bonus Track: Gaucho’s lost contender, “The Second Arrangement” (demo)

Three weeks of work disappeared when an assistant engineer accidentally erased most of the tracks on Steely Dan’s multitrack master for this lost Gaucho track. The song has been periodically performed live on Steely Dan’s tours when devoting an evening’s set list to “Rarities.” This demo version, rescued from a cassette copy, survives in various edits online.

Bonus Video: Keith Jarrett’s “Gaucho” influence

Recorded for his 1974 album, Belonging, this Keith Jarrett piece performed with his European quartet was a favorite of Walter Becker and Donald Fagen—and later became the topic of Jarrett’s successful lawsuit, earning co-writing credit and publishing royalties on “Gaucho,” the title track for Steely Dan’s seventh album. Here Jarrett performs the piece that year, with tenor saxophonist Jan Garbarek featured.

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationNo mention of My Rival!