The Blended Shane MacGowan: On the Death and Life of a Genius

by Colin Fleming The passing of Shane MacGowan at the age of 65—and at the start of the Christmas season, no less—is producing hosannas a’plenty on behalf of the Pogues’ 1987 anti-hero of a Christmas song, “Fairytale of New York.”

The passing of Shane MacGowan at the age of 65—and at the start of the Christmas season, no less—is producing hosannas a’plenty on behalf of the Pogues’ 1987 anti-hero of a Christmas song, “Fairytale of New York.”

It’s a Christmas carol borne of—and born in—the gutter, with MacGowan, and the late Kirsty MacColl, singing a duet that’s equal parts naughty and nice, but wholly loving in the end.

If there’s a popular tune of Yule in danger of being cancelled, it’s this one, with less than bonhomous lyrics about “an old slut on junk” and pronouncements of “You scumbag, you maggot/You cheap lousy faggot,” and yet it’s among the most beautiful works of art I know. It lays you out in the best possible way.

That was MacGowan’s art—the bringing together of the sacred and profane, the real guts of life at both ends—and we’d do well to infuse a portion of his lesson into our lives in an increasingly partisan world where boxes with tight lids are the norm.

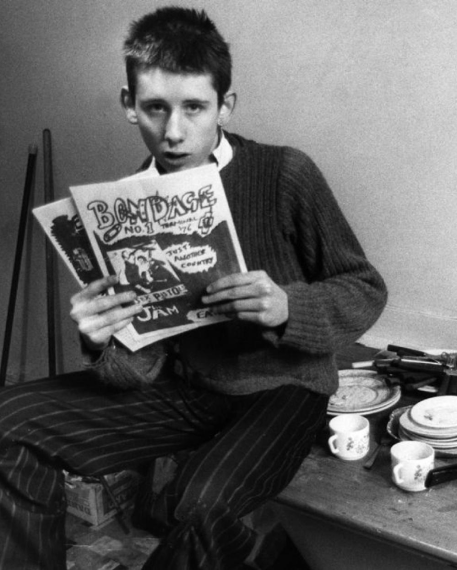

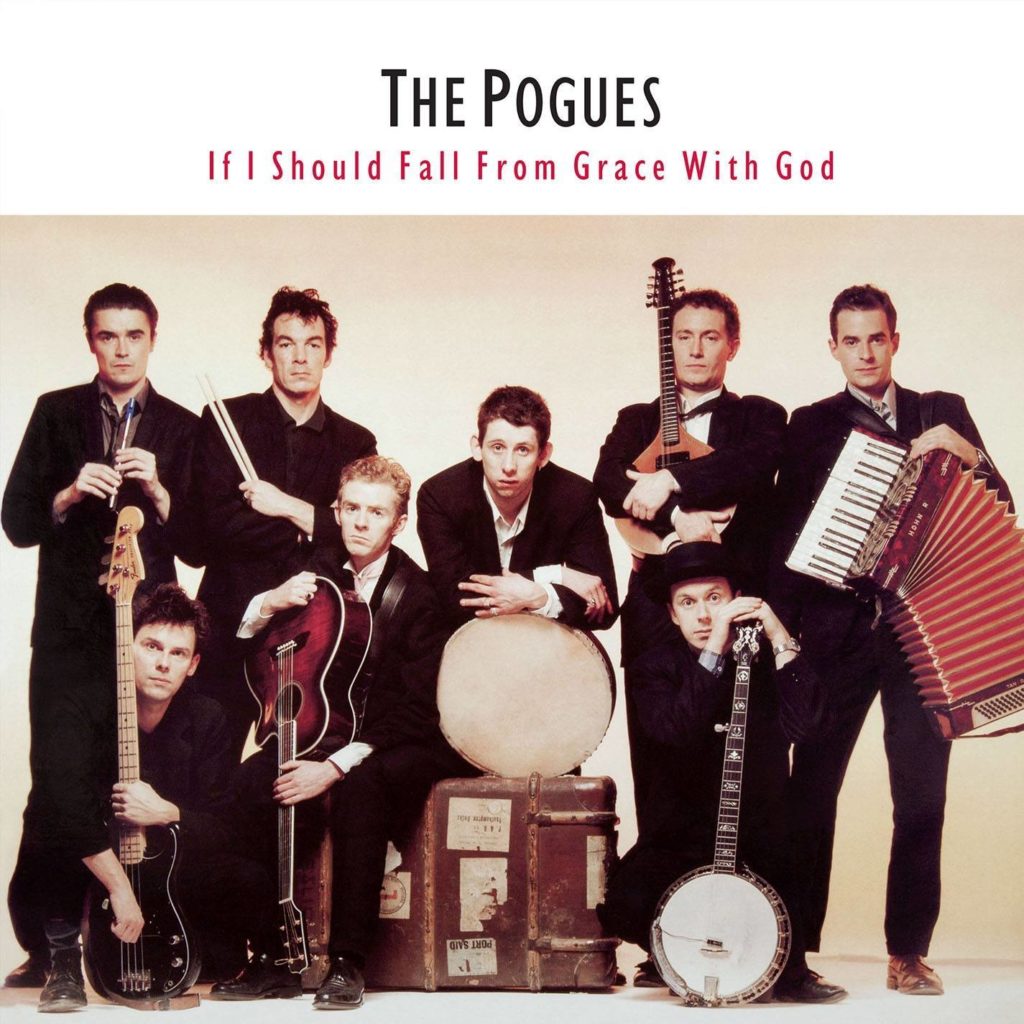

I fell hard for the Pogues as a teenager—into a form of grace, you might say—listening to albums like Red Roses for Me (1984), Rum, Sodomy and the Lash (1985) and If I Should Fall from Grace with God (1988) on a near daily basis, as if failing to do so would stop me from fully becoming myself.

Many of the lyrics were by MacGowan, a man who lived in such a self-destructive manner that there are now people giving thanks that he made it as far as he did.

I love art more than anything. It’s why I live. But for all of the artists and their works that I’ve loved, very few have altered me at the level of who I am. Shane MacGowan was one. During a crucial period, he all but doubled as a keynote speaker within my soul.

Having heard a song like “The Sick Bed of Cuchulainn,” this rush of punk, cowboy music and bastardized Irish balladeering, I thought, this is it, right here. This is how you do it—even as I wondered, “Wait…this is allowed?”

Some of the best musical art makes us ask that question, whether it’s Louis Armstrong’s “West End Blues,” Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come,” the Jesus and Mary Chain’s “Upside Down.” The very concept of what a person can do or create morphs for us within that moment of experience, and I’m confident that’s what it was like for a lot of people when they first heard the Pogues.

MacGowan’s genius—and the label fits—was in how he saw life as an amalgamation of extremes, this vast pooling together in which contrast produced clarity—and grace, if one is open to rising toward it.

Everything on one side of the street eventually comes to the other, whether we like it or not, and the sacred and the profane ride together. More than that, each is what it is in part because of the other. They are foes, foils and even companions. This is the sticky stuff of being alive and human, and MacGowan understood it better than most ever have.

We try so hard to impose these demands on life. We have rules, agendas, assorted strange gospels of this which shall never mix with that. We make friends former friends if they believe a given thing that we don’t, and we excel at isolation. Physical isolation, mental, emotional, psychological and spiritual.

God comes up a lot in MacGowan’s lyrics with the Pogues, but you may take God or leave him as you listen, the same as you can in life. God isn’t even necessarily God in a song like “The Broad Majestic Shannon,” in which people gamble and curse and flirt as the sounds of the rosary are heard from a distance. The real god is openness, wonder; an acceptance of the evinced blend.

For all the sonic bile with which MacGowan regularly spat the words of his songs, a gentleness is often in evidence at the center of their narratives, the wisdom of one who is both observer and participant. The individual who sees, learns, incorporates as they go along, so that they may go better.

Related: Other musicians that have died in 2023

The Pogues at their finest were as fierce as the young Clash—it’s little wonder that Joe Strummer thought so much of them—but they were also long on tolerance thanks to MacGowan’s story-songs with their stabilizing roots of self. Watch, listen, learn, they instruct us—even if you’re out behind the pub and someone’s about to kick you in the balls.

Unfortunately, the Pogues, at least Stateside, are mostly known for “Fairytale of New York,” and thus only come ’round once a year. The song lifts its title from a 1973 novel by J.P. Donleavy about a neophyte undertaker who has lost his wife and wants to die himself. It’s a comical, uplifting book, and if you’ve read it, the nod from the song is plain: reality is always a composite.

There is nothing any of us can do about that save accept it and try and live the best we can in following. This requires a broad mind, and less of an agenda or a need to declare, “That’s bad! I’m out!” Or “How dare you! Time to make you go away!”

We tend to be emotionally partisan and hyper-insistent with our feelings. How often do we encounter someone saying that they’re living their best life in an attempt to run roughshod over reality? But we know that they drink too much, they’re lonely, angry. We may be this person—chances aren’t exactly unfavorable, are they?

This is why I think MacGowan’s music can do so much good right now. We may insist on whatever we want, but reality is going to realtiy.

In following, you’d be hard-pressed to find a Christmas song more real than “A Fairytale of New York.” I love it, but how real is Nat King Cole’s “The Christmas Song”? I’d wager that no one within eyeshot of this piece will be roasting any chestnuts this year.

But our own personal hardships? Family stuff? Relationship issues? Things we’ll say and text—and think—that we’d hate for the world to hear and see so we pretend like we’d never do anything like that? Our pain? Fears?

How often have we had grand plans that failed to come close to materializing, which saddened us to a degree that we missed out on a lesser return which could have made for something awesome itself, only we never found out?

What has our insistence on ideological or political stances of “my way or the highway!” cost us?

What are we less capable of feeling than at times previously? What do we miss? Whom do we miss? What do we forfeit from inside ourselves?

The music of MacGowan and the Pogues is some of the most urgent you’ll ever experience. That immediacy is stunning whether it’s the first time you’re hearing “Boys from the County Hell” or the thousandth, all while being simultaneously laced with the quality of acceptance—which isn’t resignation.

Acceptance is more like that which allows us to get started. We feel like we are both moving and about to be in motion when we listen to the Pogues.

MacGowan’s “Body of an American” is a veritable novel in the space of song, and it begins with one juxtaposition after another. Some poor kids are hotwiring a car outside of a place where a wake is taking place. It’s this scene of utter solemnity, but for contrasting reasons; the hooligans don’t want to get busted, and the people inside are grieving.

And then there is this turnaround—this sonic 180—unlike anything I have ever heard. Drinks are passed in the room where the dead man lies, lips loosen, a lyric of a song is suggested, someone sings a line, someone else adds another, and then this actual song is suddenly careening as if it had been all along.

There’s no listening experience like that moment, but so much of our lives are this way. Reality comes at us fast, and so did MacGowan and the Pogues.

The key, the latter seemed to say, was to get atop the wave and see what there was to be seen. Note what X revealed about Y and how Y might have had a bit of X in it all along. Life is messy because life holds beauty. Fittingly, Shane MacGowan himself was both a mess and beautiful.

Raise a glass for this gloriously flawed man this holiday season, and hear what this music has to tell us. Let it cascade over those walls we’re bent in putting in place. They’re artificial constructions anyway.

If anyone carps at you for saying as much, take a lesson from Shane MacGowan’s old band, and reply with your own version of Pogue Mahone. And perhaps give them a hearty embrace, too. It’s all about that blend.

Watch MacGowan and Kirsty MacColl sing “Fairytale of New York”

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.