Woodstock ’69 Through the Lens of Photographer Henry Diltz

by Greg Brodsky

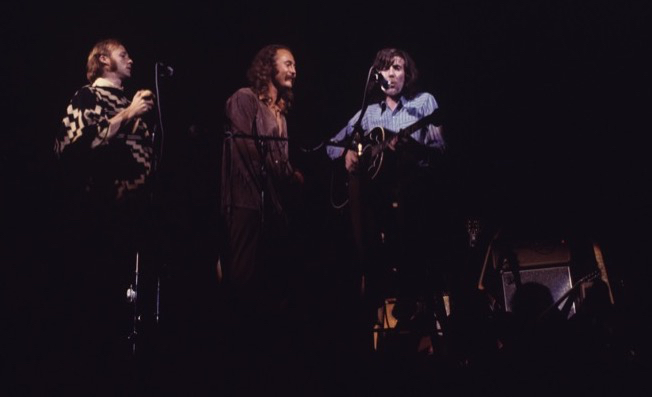

Crosby, Stills & Nash at Woodstock “I had the Golden Pass. I was working for the producer.” (Photo © Henry Diltz; used with permission)

As a touring musician himself and as a longtime denizen of the Los Angeles music scene, Henry Diltz’s friends were fellow musicians. In 1966, he acquired a camera and quickly discovered a new skill. “I just watched and waited and took photos as they happened.”

Soon, he became a much in-demand photographer for the area’s burgeoning music scene, thanks in part to his shared experience as a successful, working musician.

As the decade continued, Diltz shot memorable photographs of his friends and fellow musicians, including the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, the Mamas and the Papas, Crosby, Stills and Nash, Joni Mitchell, and many others, who lived in the Laurel Canyon area.

Related: Our conversation with Diltz on the region’s ’60s music legends

As the decade was in its final months, a new opportunity arose for an assignment at a gathering in upstate New York that August. “My phone rang one day and it was my old pal, Chip Monck,” he recalls. Monck was in charge of lighting for many of the big music festivals of the era, including Monterey Pop, and the two met in Daytona Beach, Fla., in 1963, where Diltz was performing at a folk concert.

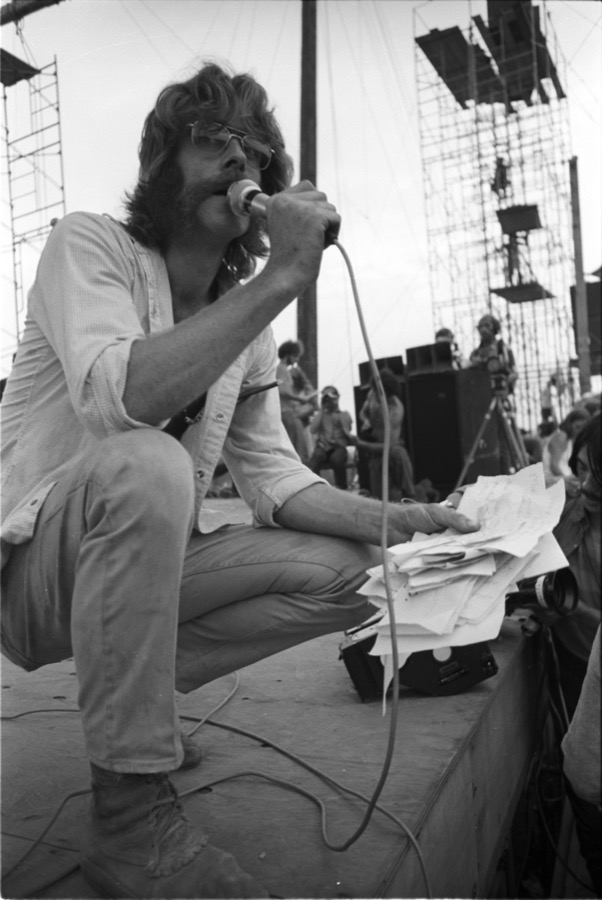

A self-portrait of Henry Diltz, on one of the Hog Farm buses at Woodstock (Photo © Henry Diltz; used with permission)

“Chip called me and said, ‘Henry, we’re gonna have a heck of a festival out here in a few weeks. You should come.’ His friend was speaking, of course, about the Woodstock Music and Arts Fair. “I said I had heard about it and would like to but I don’t know any of those people. He said he’d talk to the producer.

“The next day, Michael Lang called and said, ‘Chip says we need you. I’m sending you a roundtrip airline ticket and $500.’ I wasn’t married at the time; I was free as a bird. Have camera, will travel. So whoopee… new adventure!

“I zipped out there on TWA, two or three weeks before the festival. I got a rental station wagon, and they put me up in a little rooming house with some of the other people that were working on the grounds and on some of the artworks there.” Lang and his partners had just moved the festival west to Bethel, N.Y., from Wallkill, about an hour’s drive (without traffic!) where local officials had rejected the offer to host the festival.

All hands on deck, including Michael Lang (Photo © Henry Diltz; used with permission)

All hands were on deck.

“They were just beginning to build the stage,” says Diltz, “and the big metal lighting towers were going up and the sound towers. There were trucks and hippie carpenters on that big wooden platform, hammering and sawing with their shirts off and their long hair. Sun shining. The view from there was this hill, going up to the crest.”

They were, of course, invited by Max Yasgur, whose farm was the largest dairy operation in Sullivan County in the foothills of the Catskill Mountains. Yasgur offered the promoters his just-harvested alfalfa field for the festival site. The sloping land formed a perfect natural amphitheater.

“They were just beginning to build the stage” (Photo © Henry Diltz; used with permission)

“This solid green alfalfa blowing in the wind,” recalls Diltz. “It was this feeling that it was like an aircraft carrier on this green sea. You go around through the grounds, through the woods, and that’s where the hog farmers were setting up all the camping places. And you’d go in another direction and there’d be a bunch of art people putting up structures for people to climb on, and painting signs.

“There was all this activity going on. Besides Chip, I also knew Mel Lawrence, who was in charge of the grounds. He had worked on the Miami Pop Festival and I knew him well. He was a guy I took acid with in the early ’60s in LA.”

“What the heck are those people sitting up there?” (Photo © Henry Diltz; used with permission)

In the weeks before the Woodstock festival began, Diltz would spend time walking around the grounds with Lawrence and his little dog, Otis. “And we’d walk and walk and it was like summer camp. Nobody told me what to do. I was just there to document. So whatever I saw, I took pictures of. And, wow, that was just wonderful!

One day, up on top of that green alfalfa hillside, there was a little knot of perhaps ten people sitting up there. Diltz remembers thinking, “What the heck are those people sitting up there? Because it had been two or three weeks of just nothing up there.

“The next day, there were a lot more people and then two days later there were 450,000 people and I could no longer drive my station wagon a mile down the country road to get to the rooming house. So I slept in it parked behind the stage.”

Chip Monck at Woodstock (Photo © Henry Diltz; used with permission)

[Once the festival started, Lang realized he needed someone to handle PA announcements for the enormous crowd and enlisted Monck, with his booming voice, to do double duty. As Monck notes in Lang’s terrific 2009 book, The Road to Woodstock, “You can actually see my knees knocking together! I was terrified!”]

Says Diltz, “And then I mostly just stayed on stage, doing what I knew how to do. All of the other photographers were down on the pit looking straight up at the performers. But I was on stage. I had the Golden Pass, you know? I was working for the producer. In fact, the film crew had a little plank walkway built just about three feet below the lip of the stage so that they could walk on that and put their elbows on the stage and film. And I would go out there at night, photographing, and some of the people would say, ‘You can’t be out here. This is just for the film crew.’ And, I’d say, ‘No, I’m working for Michael Lang. I have an all-access pass. I can be here.’ A little gentle shoving.”

Listen to Monck on the PA

“I was right there. The best seat in the house,” says Diltz. “A couple of feet away from Sly and the Family Stone, and Janis and The Who.

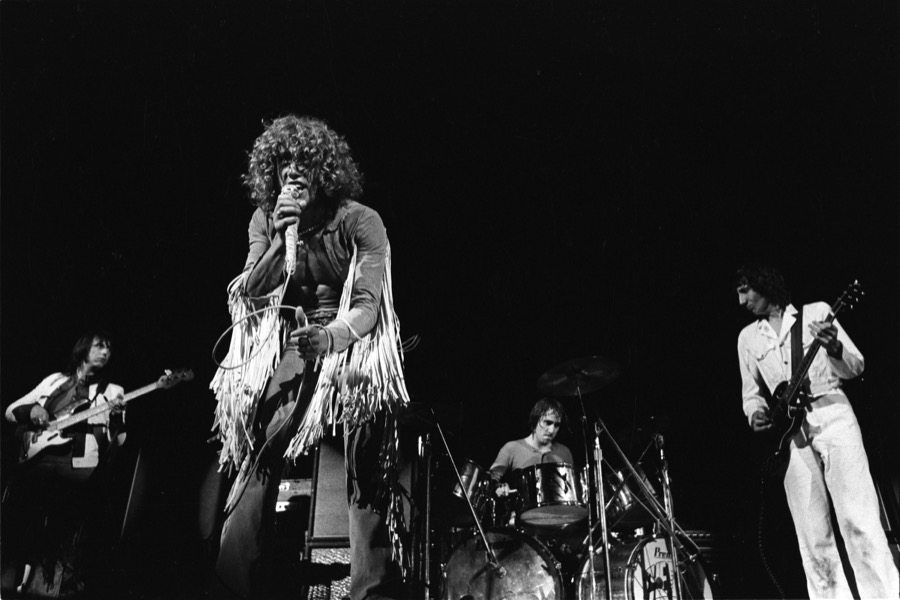

The Who at Woodstock (Photo © Henry Diltz; used with permission)

“When The Who played, I was so close, I couldn’t even get a group shot because with my widest angle lens they were still outside the frame. There was just one [instance] that I was able to get all four of them in one black-and-white shot.”

Related: Where are the Woodstock performers today?

Diltz, born September 6, 1938, was still just 30 years old when he shot the festival.

Après le deluge (Photo © Henry Diltz; used with permission)

Today, he reminisces about the camaraderie of those times. “I just felt at home on the stage as a musician. We were kind of a brotherhood. A club. Everybody knew each other. All I knew were musicians. That was my life. We lived a certain lifestyle. We’re up all night. We sleep late. We see each other at clubs. We hang out. We smoke pot. That was my whole group of friends: musicians, always.

“When I took the pictures, I didn’t try to be front-and-center. I wanted to observe what was going on without influencing it or changing it. That’s the essence of it.”

Diltz’s iconic works are available for purchase at the Morrison Hotel Gallery, which he co-founded.

Henry Diltz at a 55th anniversary exhibit of his photos at the Morrison Hotel Gallery in NY’s Soho neighborhood, Aug. 11, 2024 (Photo © Greg Brodsky)

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationI remember many nights going to see the Modern Folk Quartet in coffee houses in LA, from Stan White through Jerry Yester. Tad Diltz was always my favorite in the group. So glad to see him getting recognition on CNN and with this nice article.