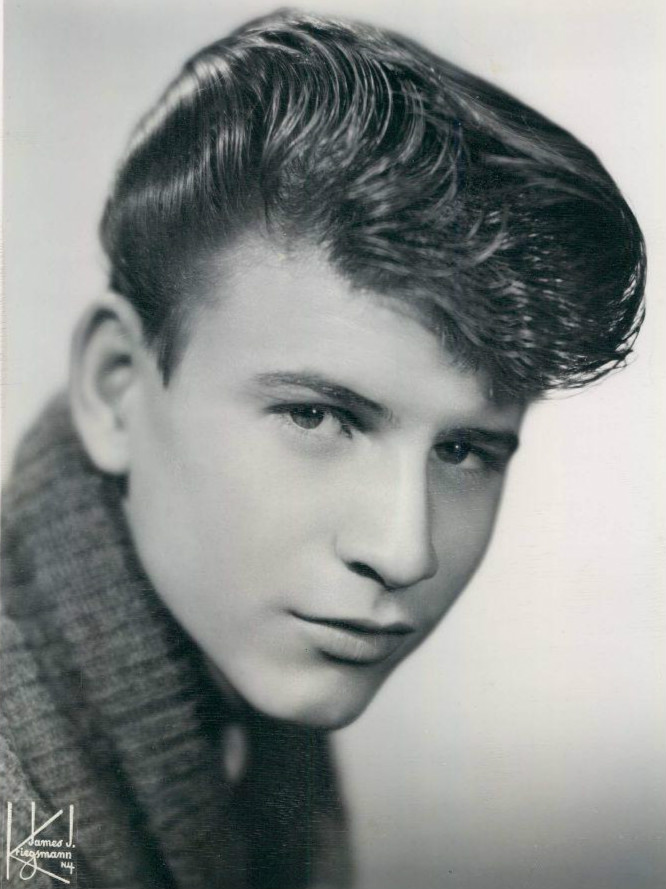

The death of singer/actor Bobby Rydell on April 5, 2022, at age 79 reminded the world of a golden age of entertainment, when a clean-cut kid from Philadelphia with a serious pompadour and even more serious talent could get a ton of exposure on television and soon find himself idolized by millions.

The death of singer/actor Bobby Rydell on April 5, 2022, at age 79 reminded the world of a golden age of entertainment, when a clean-cut kid from Philadelphia with a serious pompadour and even more serious talent could get a ton of exposure on television and soon find himself idolized by millions.

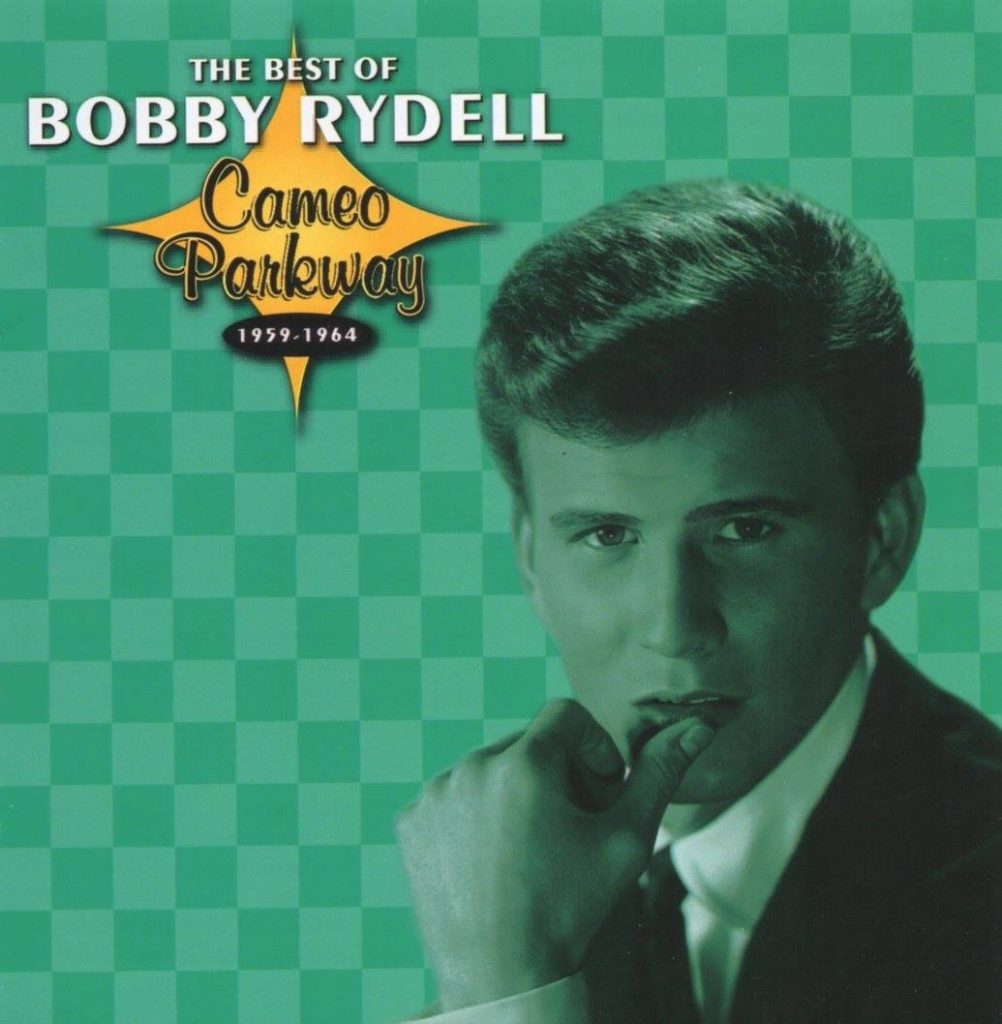

Rydell, who was born Robert Ridarelli, was a natural performer, singing and playing drums from the time he was a child. Beginning in 1959, he recorded a string of huge hit singles for the Cameo label that epitomized the often-maligned period between the initial burst of rock ’n’ roll that gave us the likes of Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly and Little Richard, and the arrival of the Beatles in 1964.

Rydell’s career as a hitmaker drew to a close around the time that the British invaded, and there were some lean years for the next couple of decades. Then, in 1985, he, along with fellow Philly ex-idols Frankie Avalon and Fabian [Forte], began touring together as the Golden Boys, reprising their hits for crowds of aging boomers who remembered those days fondly. The trio continued to find success with the package for decades.

In 2003, Rydell sat down at his home outside of Philadelphia with future Best Classic Bands editor Jeff Tamarkin. Most of the interview has never been published—until now.

Best Classic Bands: You were born on April 26, 1942, and raised in South Philadelphia. How would you describe your neighborhood?

Bobby Rydell: Very Italian. Matter of fact, Frankie Avalon was born half a block away from me.

Did you know him growing up?

I did not. It’s strange: In South Philadelphia, from one street corner to the next, it’s like a different hang, and you really don’t know the people from the next block. Fabian and I used to attend a place called the South Philadelphia Boys Club. I used to shoot pool, and he was more or less a jock. He played basketball, some boxing and stuff like that. And Avalon lived two blocks away from Fabe and me on 9th Street.

Watch Bobby Rydell sing his hit “We Got Love” as part of a Golden Boys concert. The group also featured Frankie Avalon and Fabian.

What do you remember most about your childhood?

I remember the neighborhood movies. At that time, you used to go to a movie at about nine, 10 o’clock in the morning, and not get out till about six o’clock in the evening. You’d watch all of the serials, 26 cartoons. And then of course there was the games that we used to play in South Philadelphia, like Buck-Buck, which I think in New York was called Johnny on the Pony. We’d have a game called Half-Ball, where we’d cut off a broomstick and cut the ball in half. Stick Ball—all of those of things are very, very fond memories.

Was anybody in your family in show business before you?

From what I can remember, my grandfather, my mom’s dad, was in Italian vaudeville.

How was that different from regular vaudeville?

I haven’t a clue (laughs). My grandfather used to dance and sing. My father was drafted and he would write my mom, and vice-versa, and my mother would say to my dad, “The baby’s always singing. Everywhere I go, he’s always singing.” And my father wrote back, saying, “Who knows, maybe one day we’ll have a star in the family.”

You were a big jazz fan growing up.

I was always a big jazz fan. I was never really a rock ’n’ roll fan. We used to have a theater in Philadelphia called the Earl Theater. At that time, they used to bring in all the big bands, people like [Tommy] Dorsey and Tex Beneke and Artie Shaw. I remember seeing [drummer] Gene Krupa with the Benny Goodman band, and I said to my father, “I want to be him.” I started playing drums at about five years old.

Frank Sinatra was a particularly big influence on you.

Very big. The first time I met Sinatra was at the Copacabana in New York, back in the early ’60s. [Comic] Joe E. Lewis was working the Copa, and at the end of the show, Sinatra was escorted out and I went upstairs into the lounge to say goodnight to [club owner] Jules Podell. I said, “Jeez, Mr. Podell, all I wanted to do was shake his hand.” And from out of nowhere, Frank came in through the kitchen doors into the lounge. Jules said to me, “You want to meet Frank?” He gave [Sinatra] a bang on the shoulder and said, “Frank, I want you to meet the kid.” And he stood up, with those blue eyes, and he put his hand out and said, “How you doin’, Robert?” He always called me Robert. I said, “Fine, Mr. Sinatra, how are you?” He says, “I’m doing wonderful. Would you care to join us?” I said, “It would be my pleasure.” He said, “What do you drink?” I said, “Ca-ca-Coke.” I figured if I said scotch and water, he’d slap me in the face. But I’ve always been a big fan of Sinatra’s. Just the way he told stories and the way he sang, the way he phrased.

You were performing in clubs as young as seven.

Yeah, if I had any talent within me whatsoever, my dad was the first one to see it. My mother thought he was crazy. He said, “No, he has talent.” He used to take me around to clubs here in the Philadelphia area and ask the owners if it was OK if his son got up and did a few imitations and sang some songs. I enjoyed doing that, but I always had a knot in my stomach before I went on. I always used to get nervous as hell. But I must say I was pretty good. So, yeah, I started off very young.

When did Robert Ridarelli become Bobby Rydell?

Well, actually on the Paul Whiteman [TV] show. Whiteman couldn’t pronounce Ridarelli. My dad came up with Rydell.

You and Frankie Avalon had a band around 1956 called Rocco and the Saints, is that correct?

Frankie and I used to go around doing USO shows and veterans hospitals. Frankie had a band, and then later on he joined a band called Rocco and the Saints. I basically got up and did my impersonations and sang. Frank and I go back to the early ’50s.

You made a couple of records with small labels before signing with Cameo Records.

There were a couple of guys from Washington, D.C., whose names I do not remember, and they had a label called Veko. I recorded songs called “Dream Age” and “Fatty-Fatty.” They were absolutely terrible. That was my first time behind a microphone in a recording studio, in Washington, D.C. One of the first records I recorded for Cameo was a song called “Please Don’t Be Mad.” It was a doo-wop kind of a record.

How did you get signed to Cameo-Parkway?

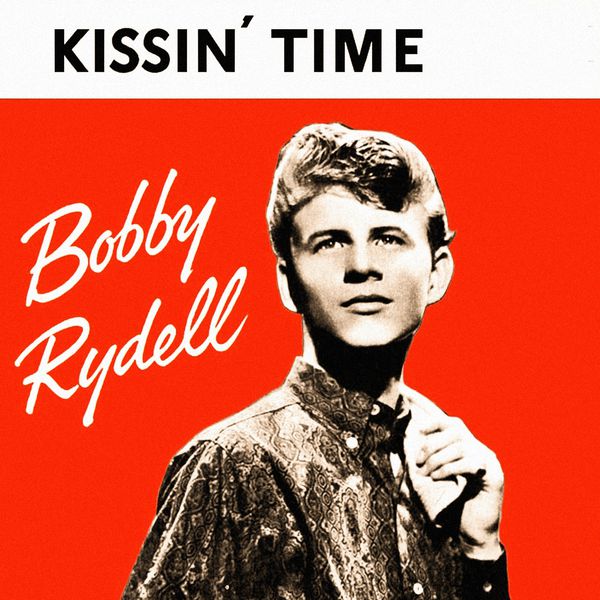

Well, it was a local label, just Cameo at that time. We had exhausted [trying to sign with] the major labels. I auditioned for [Cameo co-owner] Bernie Lowe, who was the piano player for Paul Whiteman. And he put me together with a kid, and we did a record—I think it was called “Buddies.” It went, “Buddies, buddies, the best friends in the world. But two friends can’t be buddies in love with the same little girl.” Something like that. I recorded three tunes, and they all bombed. I said, “The recording business is not for me.” What I loved to do was play drums. And then all of a sudden, Bernie Lowe and Kal Mann [the other co-founder of Cameo] wrote a song called “Kissin’ Time.” It was at their old studios on 1405 Locust Street. Two-track, recorded it with a group called Georgie Young and the Rockin’ Bocs. And lo and behold, that became the first hit record, in the summer of ’59.

How did the record break and find its way to the top 20?

How did the record break and find its way to the top 20?

Bernie Lowe used to take the songs up to Dick Clark, the three prior recordings, and Dick would just say, “It’s not in the groove.” Then when they took the fourth record, which was “Kissin’ Time,” and Dick played it in his little office in the WFIL studios, he said, “This is a hit.” Well, it named every city in the United States practically. The opening lyric was, “They’re kissin’ in Cleveland …” and I think that’s where the record took off.

Did you have any input at all in the songwriting of your records?

Did you have any input at all in the songwriting of your records?

Nothing whatsoever. No. I would sit either with Bernie Lowe or Kal or [arranger] Dave Appell. Dave played guitar, and he’d teach me the song, the chordal structure. Here’s the lyric, here’s how it goes. This is the melody, so on and so forth. Almost everything you saw on Cameo-Parkway was Lowe, Mann and Appell. Kal did most of the lyrics. Dave did all of the arrangements. And Bernie was the boss.

Was there any sense of building a career for an artist at that time, or did they just expect you to fade away when the kids moved on to someone else?

At that time, building a career for the artist was getting to do the cabaret circuit. You weren’t just an artist who went on a Dick Clark show to lip-sync your record. You wanted to nurture your career and show as much talent as you possibly could. I think it was ’60 or ’61 when I first worked the Copa, and we recorded the album Rydell at the Copa.

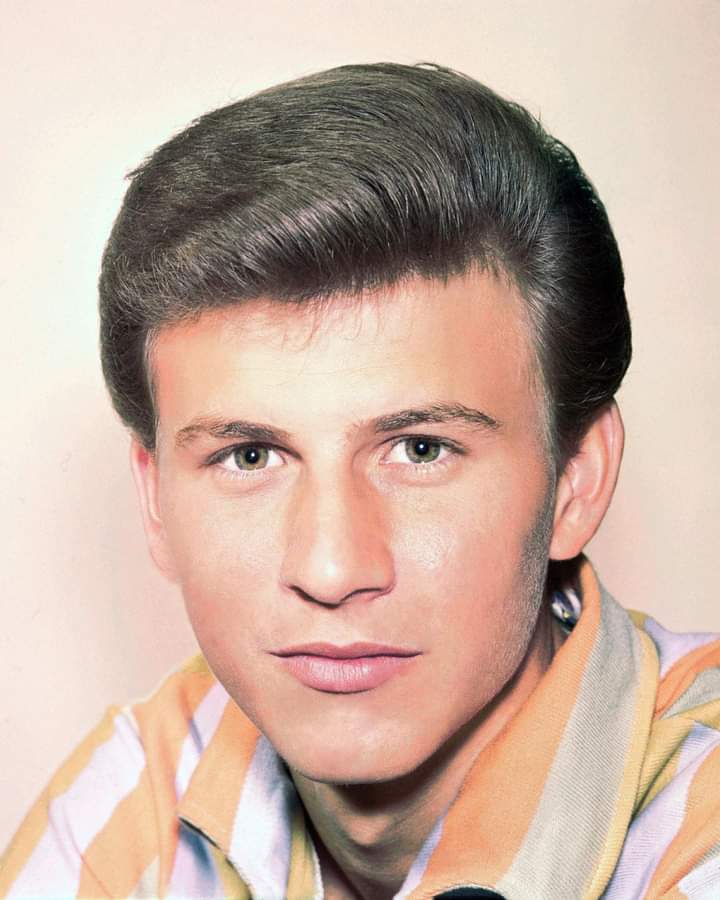

Another important factor in being a success at that time was image. I was reading an old article and I think it was your manager who was asked, “How did you shape Bobby’s image?” And he said, “What image? This was him.”

Exactly. There was a girl by the name of Connie DeNave, who was my publicist in New York City. She would say to [my manager] Frankie Day, “We got to get him involved in something, like a paternity suit.” And Frankie said, “Nope.” Frankie never would get involved with any of that stuff.

And they had to keep your relationship with your future wife Camille under wraps.

Yeah, because if you’re a, quote, teenage idol, whether it be me, Frankie Avalon, Paul Anka, Fabian, every girl out there thought at one point they had a chance to marry you. I dated Camille for 10 years before we got married. [We would say] “This is my cousin,” or “friend of the family.”

Was it a positive experience for you to be labeled a teen idol? Did it restrict you from doing certain things?

Was it a positive experience for you to be labeled a teen idol? Did it restrict you from doing certain things?

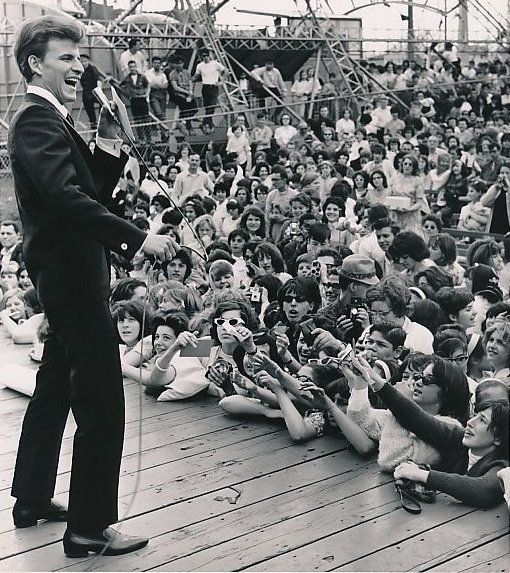

Back then, you had every girl in the world wanting you, screaming and hollering and crying.

Be honest now. Did that ever get old?

It did! (laughs) They wouldn’t pull the hair so much, but they would go for a tie or a cufflink. I remember one time, I guess it was the Dick Clark Saturday Night Show, and I was doing “Kissin’ Time.” You wanted to get a response from the audience. I was lit for the cameras but I stepped out of the spotlight, and whoever the director or the producer was, they were hollering, “Get back! Get back, you’re out of the light!” But, of course, you wanted to go down and have the kids screaming because it was network television.

It must have been exciting though.

It was. It was exciting and scary. You never knew what the heck was going to happen.

The next hit after “Kissin’ Time” was “We Got Love.” What do you remember about recording that one?

“We Got Love” was recorded at Bell Sound in New York. It took us three days to record “We Got Love.” Bernie Lowe would tell Dave Appell, “I can’t hear the bass, man. I can’t hear the bass. There’s something wrong with the bass. The bass ain’t right.” Then we went in the second day, and there was something else that wasn’t right. From what I can remember, I think the recording that came out was about the third recording on the first day, after all of that.

“Wild One” was the next big hit.

I remember Dave Appell, with a pipe in his mouth and a guitar, in the back seat of the limo, said, “When we get back to Philadelphia, this is going to be your next song.” Then he started on the guitar, doo-da-doo-da-doo-doo-da-da-doo-doo. “Oh, wild one…” And we went back home to record “Wild One.” The disc jockeys started playing the other side [of the single], “Little Bitty Girl,” at first, and then they flipped it over, and “Wild One” proved to be the very first million-seller.

The next big one was “Swingin’ School.”

Dick Clark had his first movie, titled Because They’re Young, and he needed a song for one of the parts in the movie. He approached Bernie and said, “I need you to write a song for Bobby for my first motion picture.” He set the scene for them: “The movie opens up, the kids are driving to school, listening to their favorite local radio station, their favorite local disc jockey.” That’s how “Swingin’ School” came about.

Your story wouldn’t have been the same without Dick Clark. Is it fair to say that he took you from being a local sensation to a national phenomenon?

No doubt about it. You got to figure that when the kids came home from school, 3:30 in the afternoon till five o’clock that evening, everybody tuned in to American Bandstand to see what was the latest dance, the latest craze, the way the kids were dressing, the way they combed their hair. And, of course he would play a record five days a week, so it got tremendous exposure. I always say that Dick was the grand-slam guy. He had that much power.

You also did the Caravan of Stars tours with Dick, with many of the day’s biggest artists all crammed into a bus going from town to town.

They were a lot of fun. I think I was 18 at the time, and I’m on the road with the Coasters, the Drifters, the Skyliners, Clyde McPhatter, Dion and the Belmonts, LaVern Baker, Paul Anka, Lloyd Price. A lot of camaraderie. And, of course, back then there were times when the black acts had to get off and go eat somewhere [different from where the white artists ate] and use a different bathroom. That’s the way it was back then. I didn’t care if someone was blue, black, green, yellow, purple. We were just recording artists, and we loved it. We never had any animosity between anybody.

Related: Our obituary of Bobby Rydell

The next big hit was something different for you, a cover of “Volare,” which had been a number one hit for Domenico Modugno.

We went into the studio in New York; I think it was the old RCA building. Bernie Lowe, Dave Appell and Kal Mann didn’t like the way the album turned out as a whole, but on that album, we recorded “Volare,” “Sway” and “Old Black Magic.” After “Swingin’ School,” we needed another record and they went back into the studio, and listened to “Volare,” and they added the girls [background singer]. They added “whoa-whoas” and “yeah-yeahs,” and so on and so forth. It was a good-sounding record.

Tell me about those background singers. They were a big part of your sound. Who were they?

There were three black women; I think they were grandmothers. They basically supplied the Bobby Rydell sound. Everything had a “whoa-whoa” or a “yeah-yeah,” every one of the records.

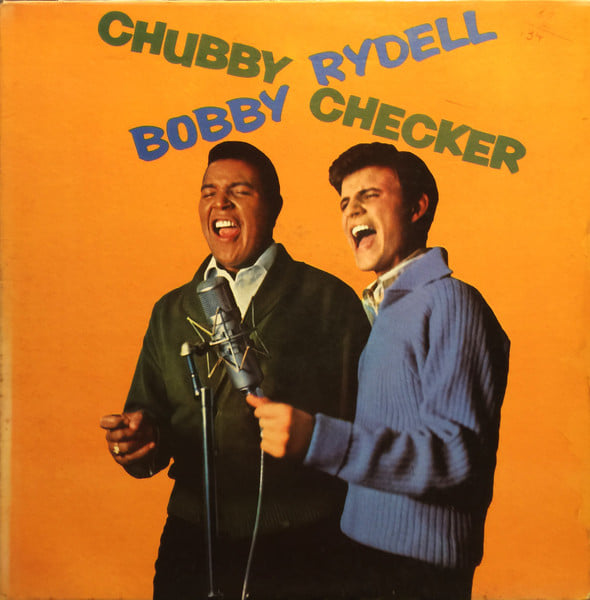

You had a hit duet with Chubby Checker on “Jingle Bell Rock.” What was he like?

You had a hit duet with Chubby Checker on “Jingle Bell Rock.” What was he like?

That came out of the album I did with Chubby. It wasn’t a seasonal album, but it just happened to come out during the holiday season. Chubby was a lot of fun.

The next hit was “The Cha-Cha-Cha.”

Yeah. Bernie Lowe was great for copying different things. He had a great ear for that. I think he copied it from the organist Dave “Baby” Cortez. It was a damned good record. He just came up with that heavy organ and said, “Let’s write a song.”

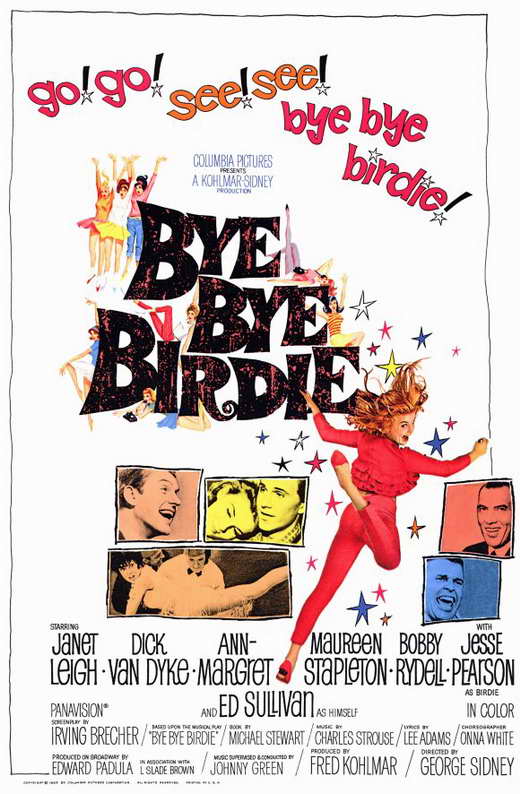

In 1963 you broke into the movies big time with Bye Bye Birdie. How did you get involved in that?

Well, I had a great director, George Sidney. He did a lot of great movies. I screen-tested with Ann-Margret. The screen test was basically they put you in front of a camera. They want to know about your personality, you sing a song, read some dialogue from the script, and then they say, “Thank you.” I went home and two weeks later, Frankie Day called me and he said, “You landed the part of Hugo Peabody.” Well, Hugo Peabody in the Broadway show was nothing. I don’t even know if he had a line; he never sang, he never danced. But, as the days went by making Bye-Bye Birdie, my script kept getting bigger and bigger and bigger and bigger. I think George Sidney saw some kind of magic between Ann-Margret and myself. We’re getting involved in the “A Lot of Livin’ to Do” number, and “One Boy,” and so on and so forth. I mean, movies are wonderful, but they can become a drag after a while because you can be in makeup at five, six o’clock in the morning, and they don’t use you all day. Plus, you’ve got to be around just in case they have to change something. I had two weeks off at one point, and he said, “Don’t anybody go into the sun.” Because then they would have to change your makeup. You’ve got two weeks off, we’re in California. What were we going to do, sit inside? We went out in the sun. You change the makeup. Color me the way I looked two weeks ago.

What was Ann-Margret like to work with? She was new herself at that point.

What was Ann-Margret like to work with? She was new herself at that point.

Yeah, I think that was her second picture. The first one was Pocketful of Miracles. [Author’s note: Bye Bye Birdie was actually her third. State Fair came in between.] She was a doll. We had a great time together.

After you made Bye Bye Birdie, you could have very easily changed your career path, moved to Los Angeles and concentrated on acting. But you decided to stay in Philly.

Yeah. I never liked L.A. Frankie Avalon said to me once, “Come on, Bobby, move out to L.A. Play golf every day.” I said, “Frank, by the time I move out to L.A., Nevada’s going to be oceanfront property.” I said, “You people are nuts out there with the mud slides, the rain, the earthquakes, the fires.” He said, “Yeah, Bob, but what about back home when it gets cold in the wintertime?” I said, “I could always turn up the heat.”

Your next big hit was 1963’s “Wildwood Days.” Why a song about a beach town in New Jersey?

Oh, it’s their national anthem in Wildwood! Are you kidding? I spent a lot of years down there. My grandmother had a boarding house there. She charged like $100 a week. Three meals a day. They would come off the beach at 12 o’clock in the afternoon, have lunch. And I’m talking lunch—spaghetti and meatballs—and then dinner. Room, food and board.

“Forget Him,” in late ’63, was the last of the major hits.

Good record. I was in London with Ann-Margret, and we were doing the command performance for the royal family when Bye-Bye Birdie had just come out. It was [recorded at] Pye Records in London. I’d met a gentleman, a songwriter and producer by the name of Tony Hatch. We went in to record an album for Pye, and one of the songs that came out of the album as a 45 single was “Forget Him.” Bernie Lowe, Kal Mann and Dave Appell didn’t want to release it because it wasn’t their publishing. But a disc jockey in Toronto, Canada, started playing the record and basically that’s how it started. It went from Canada down to Detroit and then they had to release it.

A few months after “Forget Him” was a hit, the Beatles arrived in America. What did that do to your career?

Well, we had a couple of records after “Forget Him” that really didn’t do too much of anything. So that was basically the end of the recording career, and that’s when I signed with Capitol Records. The first song I recorded was a rendition of Paul Anka’s “Diana.” It was absolutely a phenomenal record, but they had Wayne Newton on the label at the time, and he had “Red Roses For a Blue Lady.” That record was taking off, so they dropped the promotion on “Diana” and started promoting “Red Roses For a Blue Lady” and that was the end. I recorded quite a few songs for Capitol, but nothing of any consequence.

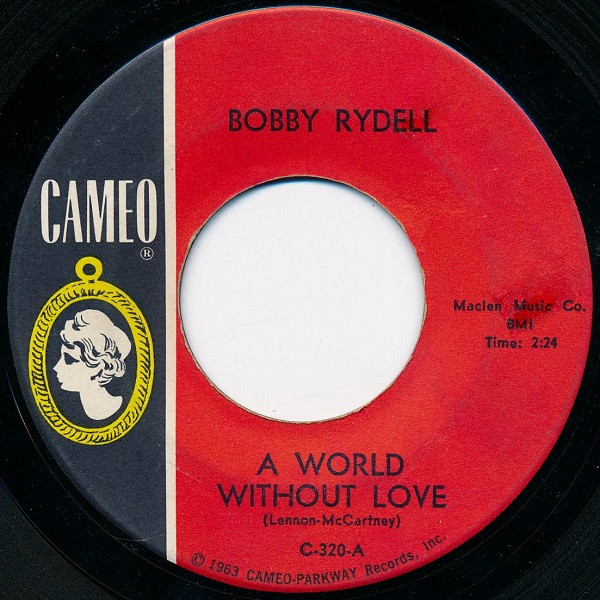

There was one last one on Cameo, your cover of the Lennon-McCartney song “A World Without Love.” Peter and Gordon of course had the number one hit with that, so yours didn’t get very far.

There was one last one on Cameo, your cover of the Lennon-McCartney song “A World Without Love.” Peter and Gordon of course had the number one hit with that, so yours didn’t get very far.

We had that in the can; that was already recorded. My manager and I were driving through New York one day, and we turned on the radio and we hear [Peter and Gordon singing], “I don’t care what they say, I won’t stay in a world without love.” We said, “What the hell is that?”

After the recordings started winding down, you basically stuck to your guns. You weren’t one of those guys that grew your hair long and started making psychedelic music.

No, I just did what I always did, working clubs, whatever was out there. I continued to work, work, work, work. There were peaks and valleys. Then in 1985 things started to turn around with [promoter] Dick Fox, who came up with the idea of three Italian kids from South Philadelphia [Rydell, Avalon and Fabian] touring together as the Golden Boys. We figured what the hell, we’ll give it a shot; how long is this going to last? And in 2003 we’re still doing it. It was that whole concept of three teenage idols, Italian, born and raised two and a half blocks away from one another. It was a great idea and we didn’t know what the hell was going to happen, but it was gangbusters. I think the first year we did 50-60 dates, then 80-90, then 100-plus. It was like the old Caravan of Stars again, going town to town on a bus. Full circle.

Bonus Video: Watch Bobby Rydell sing “Volare” on The Perry Como Show in 1960

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationReally enjoyable interview, Jeff. As usual, you asked very detailed questions that opened the interviewee up, and in this case gave us Rydell’s very human side.

While I was pretty young in his heyday, my parents had his records, so I’m very familiar with his recordings, and that voice. As evidenced by the fellow Philly crooners he’s toured with, pop stars were pretty much cut from the same cloth in that era. But Rydell has something special going for him in his voice, his moves, and, of course, that hair. I thought it was great that he acknowledged his background singers as the key to “The Rydell Sound,” but it did kind of sadden me that he didn’t even know their names. When I listen to these old recording again with fresh ears to songs I knew by heart when I was very young, the backups really were a key to the “sound” he created throughout a slew of records. Those records sound pretty damn good today, too.

Terrific article!