[Editor: This story was written in late January 2016 following the deaths of David Bowie, Paul Kantner, Glenn Frey and others. It was only the tip of the proverbial iceberg for the rest of that year and in the years that followed.]

Rock ‘n’ roll laughs at death. Rock ‘n’ roll likes waving the skull and crossbones flag. Rock ‘n’ roll runs with the devil and shoots death the middle finger.

And yet, of late, the grim reaper keeps calling. A little more frequently and disturbingly for those of us who are boomers and fans of classic rock acts. We’ve been hearing this a lot recently: that 67 – or 69 or 70 – is the new 27, the latter being that fabled premature age for young sets of rock ‘n’ rollers to perish at, the so-called “27 Club” Amy Winehouse so wished to avoid….

You know the starting lineup: Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain and, of course, Winehouse.

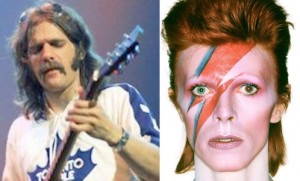

Within the past year we’ve lost Motörhead’s Lemmy Kilmister and Natalie Cole (just as the New Year beckoned), then David Bowie, the Eagles’ Glenn Frey, Jefferson Airplane’s Paul Kantner, Keith Emerson of Emerson, Lake & Palmer, and lesser-known guys like Mott the Hoople drummer Dale “Buffin” Griffin and Rainbow/Dio bassist Jimmy Bain. Plus Airplane’s Signe Toly Anderson, Earth, Wind & Fire’s Maurice White and Dan Hicks.)

Spring 2016 brought news that the multi-instrumentalist Pete Zorn had died. And Prince at just 57. Then more recently, Wayne Jackson of the Memphis Horns, keyboardist Bernie Worrell and Suicide’s Alan Vega, less well known but influential to many.

A wave of deaths of older rock legends. One that we can only expect to increase in frequency as the classic rock music generation matures.

Related: 2016 in Review… Saying farewell to so many

By now many of us have seen the Facebook posts that begin with: “They’re dropping like flies.” That’s flip black humor, but that’s what we sometimes resort to, a kneejerk reaction. Bowie’s longtime producer, Tony Visconti, spotting that comment, responded on Facebook by calling those people “nitwits” and rather thought the rockers were “dying like heroes.”

If you’re a new Best Classic Bands reader, we’d be grateful if you would Like our Facebook page and/or bookmark our Home page.

Social media death alerts spread like wildfire and as such we mourn Buffin. We learn that he suffered through a long battle with Alzheimer’s, even if we probably didn’t think about him much after Mott the Hoople folded. But there he was on Facebook’s death toll, so we RIP’d and snatched deep tracks of Mott from YouTube.

2015 was the first year that millennials out-numbered baby boomers in the general population. But I believe what’s gone down lately has given boomers a kick upside the head. Death surrounds us.

The rockers who died at 27 all died, in part, as the result of youthful misadventure. The rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle, if you will. Dice rolled, gamble lost.

The latest crop to exit Planet Earth? They’re in our demographic – or one generation up – and they’re dying if not young-ish than at least younger than we’d hoped. Because rock ’n’ roll did exude an implied promise of eternal youthfulness…

We knew that was bullsh*t, but hey like Fox Mulder, who’s back with us now on TV, we wanted to believe. Whether it was Bob Dylan, Neil Young or Sparks singing “Forever Young,” that’s what we hoped against hope for.

You can’t help but speculate that in some way years of substance abuse may have caught up with them. No overdoses, but perhaps slow internal damage. Bowie had been clean for years, but was once a huge cocaine abuser; same with Frey, who admitted as much and its effects on his long-term wellness when The Eagles were forced to postpone their 2015 Kennedy Center Honors ceremony. Lemmy only tamped down his intake of speed and booze slightly as the end neared… which is what we expected of him.

If you want to look back a bit, consider all four of the original Ramones: Joey dead at 49, Dee Dee dead at 50, Johnny dead at 55 and Tommy, the last to pass, dead at 65.

Whatever the ultimate cause of death, you have to figure these lives were lived to the max and not always with thoughts of longevity. The philosophy of live fast/die young and hope-I-die-before-I-get-old serves the id, the needs of the cocky, prideful youth. A kid can barely imagine life past 40, 50 or 60. Then, as you hit those marks – pick the one you’re staring up at – you start thinking, “This age thing, it ain’t so bad. What more is out there?”

Nineteen years ago, I was interviewing Bowie and he was talking about his time in drug hell, dealing with paranoia and crippling self-doubt. “I think I’m actually glad to be alive,” he said, adding that his present happiness may have to do with “surviving all that stuff and finding that actually getting older ain’t such a bad thing, that really, I would be left with an appetite for life.”

And when he was given the grim reality of his terminal cancer prognosis, Bowie the artist dove deep into the creative pool he knew and came up with the wrenching and achingly visceral Blackstar album. (Click here for BCB’s rave review.) And the play Lazarus. Album sales were goosed by Bowie’s death – see our story – just as Double Fantasy soared to the top after John Lennon was assassinated.

The topic of death may be anathema in today’s pop world. But many rockers have considered it for years in song.

“Death is a topic a lot of people talk about,” Iron Maiden guitarist Steve Harris told me about 25 years ago. “It’s just something lyrically, the imagery. You can write interesting things about it.”

Maiden, Metallica, Megadeth and virtually all heavy metal bands have at some point done so. As have Nick Cave, Alice Cooper, X, Jim Carroll, Richard Thompson, Neil Young, The Pogues, Lou Reed, Joy Division, The Clash, Warren Zevon, and, of course, Bowie and Motörhead.

Lemmy wrote dozens of songs that dealt with the topic – “Killed by Death,” being the best grim-humored one, and the World War I epic “1916” being the most poignant and heartbreaking. A few years back, he said to Classic Rock magazine, “Death is inevitability, isn’t it? You become more aware of that when you get to my age. I don’t worry about it. I’m ready for it. When I go, I want to go doing what I do best. If I died tomorrow, I couldn’t complain. It’s been good.”

In 1992, Lou Reed told me about his then-current album Magic and Loss: “I keep getting told, `This is too depressing. It’s about death and it’s depressing.’ You know, I must say if you look at it that way, Hamlet‘s synopsis would seem pretty down, too. Macbeth would seem pretty awful. I think of Magic and Loss as about love and friendship, and it’s a very up thing. It is very emotional, also. These are not bad things. And I don’t see why a contemporary work of music can’t contain all these things. But when they do contain these things, you’re thought of as being too cerebral, or too down.

“I remember reading this book by Saul Bellow where he was quoting Walt Whitman and he said, `Until Americans and American poetry can deal with death, this is a country that has not grown up.’ There might be something to be said about that.”

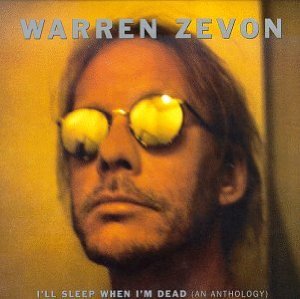

Zevon, who was 54 when he died, liked using a grinning skull with sunglasses and a cigarette image. He wrote a lot of death-related songs over the years, including one on his major-label debut album called ‘I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead.”

In “Play It All Night Long,” he sang about a damaged, dysfunctional family that was only content when they heard Lynryd Skynyrd. “’Sweet Home Alabama,’ play that dead band’s song,” sang Zevon, baritone bursting. “Turn that music up full blast, play it all night long.”

When, many years ago, I asked Zevon his intent. Is it funny? He said, “Well, it is funny, but it’s also not funny. Like it’s not intended as a ridicule of Lynyrd Skynyrd – I don’t think it’s funny that rock bands get killed in plane crashes – but then the grim, crazy stuff is funny and the overall effect is scary. It’s ambivalent.”

In 2000, when he was 53, Zevon played a short 1/2-hour radio-sponsored show in Boston. Afterwards, we talked about his then-current album “Life’ll Kill Ya.” Death is more a reality, he pointed out, “when you’re older. You start enjoying every minute or you remind yourself to. That’s what the album is for… The subjects might be darker, but the subtext might be shinier.” After his cancer diagnosis, when he was essentially given a death sentence, he was on his old pal and benefactor David Letterman’s show. Letterman gave him the whole hour for music and chat and that’s where, when Letterman asked him what he might now know that we didn’t, Zevon replied with his now famous, “Enjoy every sandwich.”

Most poignant was Zevon’s final album, The Wind, recorded as he was dying. The previous one had been called My Ride’s Here – an expression signaling the end of life’s journey. The Wind included a tear-inducing version of Bob Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” perhaps the most un-ironic song Zevon ever recorded.The resonance was obvious. And it had the gorgeous and sweet ballad “Keep Me in Your Heart.” Sang Zevon, “Shadows are falling and I’m running out of breath/Keep me in your heart for a while.” All any of us could hope for – not eternal fame or everlasting love. Just to linger for a while in someone’s heart after yours has stopped beating.

Dave Davies of The Kinks played Boston in fall 2015. We talked after the set and, of course, I had to ask about a potential Kinks reunion and the status of the ongoing love/hate relationship between the brothers. He said there was a “fair” possibility and he and Ray would meet over Christmas. Indeed, the two did play together. (See our item here.) Ray then joined Dave and his band for “You Really Got Me” on a London stage in December.

After I’d asked Dave about the chances of a reunion, I said, “Well, if you’re going to do it, you should do it soon. Because, you know, one day you won’t be able to.” He looked at me with his head cocked, a bit puzzled. I hemmed and said, “Well, I mean sooner or later, one of you will die and there goes the opportunity.”

Dave winced. But he’s a Monty Python fan as am I, and he laughed a bit ruefully, admitting the logic in it. His stroke in 2004 had nearly killed him. If one of the Davies brothers – Dave is 68, Ray 71 – was no longer with us, there would be no prospect of a Kinks reunion. Not even a remote one.

And then Dave and I had that little talk, the talk so many of us boomers often have. We remind each other to live in the moment because tomorrow is not guaranteed. We hug. We part ways.

Rock ‘n’ roll is forever young. But its players are not. Intrinsically we know that. But with the recent spate of deaths and sadly but surely more to come, we’re getting more and more accustomed to that reality.

Life is good. The end of life? It sucks.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationJohn, I reblogged your piece on my Jim Morrison Project website (http://www.jimmorrisonproject.com). If you have any objections with the reprint, please let me know, and I’ll take it down immediately. Your piece has been properly cited, and I have included a live link to this page.

Sadly, those of us “rockin on” in the 60’s … seeing the Beatles, attending the Monterey Pop Festival, the Haight in San Francisco, etc., We’ve known the time is coming as these classic rockers age and pass away…..it is a difficult pill to swallow….actually devastating for some of us…particularly Glenn Frey’s demise …. 🙁