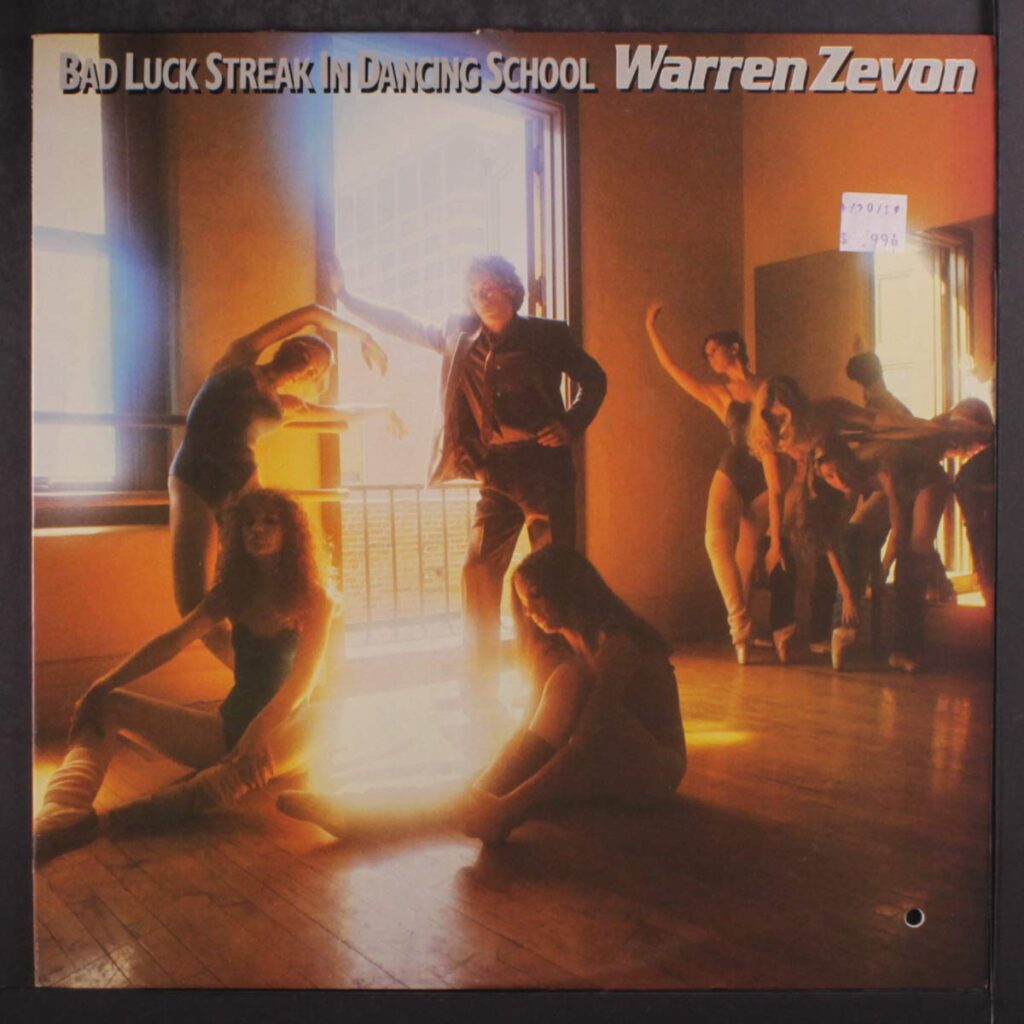

Warren Zevon Copes with Mortality in ‘Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School’

by Mark Leviton “I think everybody has their own way of coping with their mortality,” Warren Zevon told the British writer Sandy Robertson in 1981 while discussing his most recent album, Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School. “Mine is to make as broad a joke about it as I can, because it’s the best way I can balance the fear.”

“I think everybody has their own way of coping with their mortality,” Warren Zevon told the British writer Sandy Robertson in 1981 while discussing his most recent album, Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School. “Mine is to make as broad a joke about it as I can, because it’s the best way I can balance the fear.”

Newly sober after years of alcohol abuse and subsequent bad behavior, Zevon was forthcoming about his new outlook, writing his own promotional bio for the Asylum Records label: “From what I know about alcoholism, I’d say there’s nothing romantic, nothing grand, nothing heroic, nothing brave—nothing like that about drinking. It’s a real coward’s death.”

Recorded at the Sound Factory in Hollywood during 1979 and released on Feb. 15, 1980, Zevon’s fourth album reached #20 on Billboard’s Hot 100 LP chart, more than respectable even considering his previous album Excitable Boy reached #8 and spawned his signature 45 rpm hit, “Werewolves of London.” For Bad Luck Streak he included string arrangements and interludes as a homage to his teenage years hanging out with Igor Stravinsky and the composer’s right-hand man, Robert Craft.

“I can play passages from Stravinsky where I defy anyone to show me the difference between this clarinet part and this Jeff Beck lick,” he insisted to Robertson. “On Bad Luck Streak the strings are there for the same reason that I’d hire a bagpipe player; it just so happened that 12 strings playing certain notes was what I wanted in certain places more than ’Here’s a hint of classical music.’”

Zevon could also draw on the large group of friends who’d been supporting him by cutting his songs and playing with him for years, including Jackson Browne (who’d produced his first two Asylum albums), David Lindley, Linda Ronstadt, JD Souther and various Eagles. With the assistance of co-producer Greg Ladanyi, Zevon took the reins with new confidence, joking to Creem’s Toby Goldstein, “When you can walk across a room, it’s easier to consider the idea of larger and more ambitious endeavors. Greg works on the board; I just look at the colored lights and nod, shake my head, gesture, jump up and down.”

Related: Our Album Rewind of Excitable Boy

The title track leads off the LP, with Zevon on grinding electric guitar, Leland Sklar on bass, Rick Marotta drumming, Lindley playing lap steel guitar, and strings composed by Zevon but under the direction of concertmaster Sid Sharp. The lyrics are confessional, aimed at a girl the singer addresses: “Down on my knees in pain/Bad luck streak in dancing school/Swear to God I’ll change/Pauline, don’t make me beg.” (Pauline appears to be a stand-in for Zevon’s long-suffering wife, Crystal.)

Marotta does some wonderful stuff with snare rolls and woodblocks, and Lindley’s got his instrument crying. At one point, a .44 Magnum is fired into sand for punctuation. “Dancing school” is apparently 17th-century slang for a brothel; if that’s what Zevon had in mind, the album cover suggests he is being ignored by the ladies in the room, but then again Zevon isn’t exactly known for providing clear answers to his koan-like images.

Playfully gear-shifting a few decades, Zevon serves up his remake of Ernie K. Doe’s 1961 single for Minit, “A Certain Girl,” which was written by Allen Toussaint under his pseudonym Naomi Neville and is the only non-original on the LP. No less than three guitarists are employed (Waddy Wachtel, Don Felder and Jorge Calderon), with Browne and Marotta doing the wry backing vocals, and Zevon strutting and shouting with abandon. Released as one of three singles drawn from the album, it was the only song to chart, reaching #57 in Billboard.

“Jungle Work,” a Calderon-Zevon co-write, uses Joe Walsh as lead guitarist, the reliable Sklar/Marotta rhythm duo, and Zevon playing a string synthesizer. Continuing his fascination with mercenaries (see “Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner” on Excitable Boy), Zevon name-checks several military weapons as he inhabits the voice of someone who loves work where “the pay is good/And the risk is high.” The macho chest-beating in the lyrics is prime Zevon—is he celebrating or ridiculing? By the end of the track, Calderon, Marotta and Zevon are cackling background vocals behind Walsh’s high-on-the-guitar-neck wails.

Proving once again he can produce heartfelt ballads as well as ravers, Zevon plays piano and sings “Empty-Handed Heart” like his life depends on it: “Heart jinxed condition/Never sure how I feel/Trying to separate the real thing/From the wishful thinking/Sometimes I wonder/If I’ll make it without you.” Linda Ronstadt sings a poignant four-line descant while the protagonist repeatedly laments, “I’ve thrown down diamonds in the sand.” Zevon once said, “I find myself writing about violent subjects more than romantic subjects,” but it’s a measure of his genius that he does both so well.

“Play It All Night Long” has a shocking opening lyric (“Grandpa pissed his pants again/He don’t give a damn/Brother Billy has both guns drawn/He ain’t been right since Vietnam”), followed by a reference to “that dead band” Lynyrd Skynyrd and cranking up the stereo to blast “Sweet Home Alabama.” A reference to the bovine disease brucellosis and cancer continue to paint a picture of horrific “country living.” Zevon and Browne harmonize on the powerful choruses. As with the album’s title track, Marotta lays out a military snare pattern and Lindley runs the keening, emotional lap steel interludes.

The second side of the original LP starts with a song that began in Bruce Springsteen’s brain and migrated to Zevon when he heard a demo of the uncompleted tune. The two eventually finished it together, with the female character changed from “Janey” to “Jeannie.” The song’s like a compact screenplay. The opening lyrics are certainly Springsteen’s: “I was born down by the river, where the dirty water flows/And the cold wind cut through me, it cut right through my clothes.”

It’s not long before Zevon’s literary sensibility expands the plot: Jeannie’s father is a homicidal lawman who threatens the young girl’s suitor for reasons unknown. Like a modern echo of Marty Robbins’ “El Paso,” it turns out the narrator is gunshot, lying in the dirt, singing about Jeannie needing “a shooter on her side.” Once again, Walsh is the feisty soloist, Marotta/Sklar hold it all together, and Zevon plays guitar and composes for strings.

Zevon wrote the short “Bill Lee” in tribute to the Boston Red Sox/Montreal Expos pitcher who was nicknamed “Spaceman” for his radical views and outspoken directness. Lee visited Zevon in rehab and heard a tape of the developing song. The album version is minimal, with just Zevon’s piano and harmonica and Glenn Frey’s harmony.

“Gorilla, You’re a Desperado” is a goofy song even by Zevon’s standards: “Big gorilla in the L.A. Zoo/Snatched the glasses right off my face/Took the keys to my BMW/Left me here to take his place…He built a house on an acre of land/He called it Villa Gorilla/Now I hear he’s getting divorced/Laying low at L’Hermitage, of course.” Poking fun at the Eagles, he makes Browne, Souther and Don Henley croon “Gorilla, you’re a desperado” at one point.

“Bed of Coals,” co-written with T-Bone Burnett, is the album’s longest cut, a country lament that has a fine pedal steel guitar by Ben Keith, Zevon playing both piano and organ, and Ronstadt/Souther holding down the backing vocals on the choruses. The tempo drags a bit too much, as the lyrics predictably have more to say about the Great Beyond: “I’ve been lying in a bed of stone/I’ve been dying all alone/I pray for the power to turn it around/I’m too old to die young and too young to die now.”

The album ends with the anthemic “Wild Age.” Zevon seems to be saying that once “the reckless years” end, some souls can’t make the adjustment and keep running “straight in their graves.” The last minute is taken up with Zevon, Frey and Henley repeating the refrain “wild age” like they don’t want to let it go. Is Zevon still ambivalent about sobriety? Although thematically it closes the album well, overall, it’s probably one of the weakest tunes on the set.

The album is dedicated to the novelist Ross Macdonald (using his real name, Ken Millar), another of Zevon’s supports getting sober. As Zevon told Rolling Stone’s Paul Nelson, “The scariest part about alcoholism—about any addiction, for that matter—is that you credit the booze for all your accomplishments. You could be dying from drink and unable to move anything but one finger, yet still be convinced that, without another shot, that finger was going to stop, too. Ken Millar made me realize that I wrote my songs despite the fact that I was a drunk, not because of it.”

Zevon had many highs and lows, professional and personal, before his death from lung cancer on Sept. 7, 2003, at the age of 56. His final appearance on The Late Show with David Letterman on Oct. 30, 2002, is an emotional hour with the man who admitted he’d “made a tactical error in not going to a physician for 20 years.” When Letterman asked Zevon if his terminal condition had taught him anything about life, Zevon responded “How much you’re supposed to enjoy every sandwich.” In 2004, a tribute album, Enjoy Every Sandwich: The Songs of Warren Zevon, included tracks by Bob Dylan, Jackson Browne and Bonnie Raitt, Steve Earle, David Lindley and Ry Cooder, Bruce Springsteen, Don Henley and many other appreciators of the great, eccentric work of an American original.

Watch Zevon perform the title track in 1982

Zevon’s recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI mean, Bed of Coals is outright torture just as the title implies, Wild Age seems ambitious but nothing but an airy chorus, A Certain Girl goes strangely slowly, Jeannie contains more machismo than one can bear – I could go on about such a flawed work but certain tracks are unforgettable, and none more than the stripped-down Bill Lee, painfully extracted from a rare moment of emotional directness.

Zevon is a severely overlooked musician, composer, and literary genius. He would have a place in the R&R HOF if only Jan Wenner would not have held childish grudges.