Singer and multi-instrumentalist Steve Winwood was mere days short of his 19th birthday when he formed Traffic with guitarist Dave Mason, drummer Jim Capaldi and woodwinds player Chris Wood. Other than Winwood—who had enjoyed success as lead singer of the Spencer Davis Group, with hits including “I’m a Man” and “Gimme Some Lovin’”—none of the band members was especially well-known. Winwood had developed something of a reputation as a modern-day blues shouter, though the music he would make with Traffic explored far beyond the confines of blues.

Singer and multi-instrumentalist Steve Winwood was mere days short of his 19th birthday when he formed Traffic with guitarist Dave Mason, drummer Jim Capaldi and woodwinds player Chris Wood. Other than Winwood—who had enjoyed success as lead singer of the Spencer Davis Group, with hits including “I’m a Man” and “Gimme Some Lovin’”—none of the band members was especially well-known. Winwood had developed something of a reputation as a modern-day blues shouter, though the music he would make with Traffic explored far beyond the confines of blues.

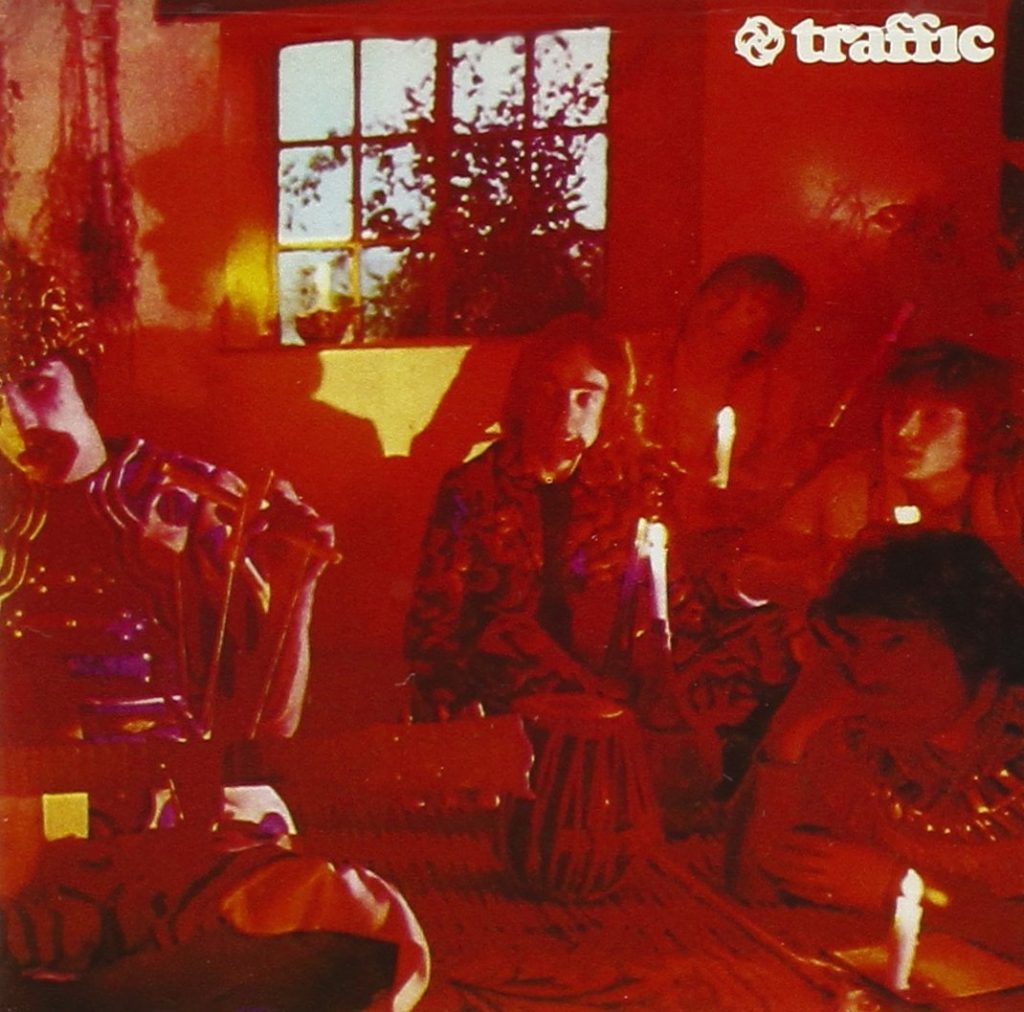

In the hands of a lesser group than Traffic, the various musical styles represented on Mr. Fantasy, released in the U.K. on Dec. 8, 1967, may well have been a mishmash; instead, they blend relatively seamlessly, and display the group’s intelligent, creative eclecticism. Unlike many of the group’s contemporaries, the original lineup of Traffic was a band featuring multiple multi-instrumentalists. That wide facility helps give the album its character: Winwood, Capaldi and Mason played keyboards; Winwood and Mason both played guitar; all four sang and provided percussion. And somewhat atypically for a drummer, Capaldi was an effective and prolific lyricist.

In retrospect, the instrumentation on Mr. Fantasy is pure 1967: the tape-based Mellotron keyboard is used often, harpsichord makes multiple appearances, and the requisite exotic Eastern instrumentation (sitar, tambura) is sprinkled across the songs. Wood’s saxophone and flute were still somewhat unusual in their use on a rock record by a group member; such duties were often ceded to session players.

The record opens with “Heaven is in Your Mind.” An insistent piano, bass and drum pattern is punctuated by Wood’s squawking saxophone and trilling flute; soon the song shifts into a different, funky tempo, with dual harmony lead vocal from Winwood and Mason. The brief chorus features yet a different tempo and feel, built around vocal and piano. In its first minute, “Heaven is in Your Mind” has showcased dazzling variety in the form of a pop song. The tune continues, spinning out three more brief verses and chorus; as the three-minute mark approaches, it dissolves into a kind of one-chord jam, highlighted by an extended electric guitar solo and supported by miscellaneous whoops and hollers.

A bit of studio chatter precedes the start of “Berkshire Poppies,” a novelty song in the English music hall tradition. The waltzing melody is played on a tack piano (an upright piano with metal thumbtacks inserted into the felt-covered hammers that strike the piano’s strings), and Winwood delivers an atypically pained, strained vocal performance. Various shouts and muttering in the mix give “Berkshire Poppies” a decidedly drunken, late-night beer hall feel.

Some odd sounds—a clock being wound, perhaps?—open Mason’s “House for Everyone.” Wood’s saxophone suggests the song is heading in one stylistic direction, but once Mason’s vocal starts, the tune reveals itself as psychedelic pop of the particularly twee British variety. Mason’s lyrics go so far as to mention treacle (the British term for the sticky-sweet substance Americans call molasses). Manically sawed violins accentuate the tune “popsike” character. The song breaks down near its end as the tempo, pushed forward by Mellotron, slows to a complete stop.

Related: BCB’s Dave Mason interview

The plaintive ballad “No Face, No Name, No Number” debuts a songwriting style Winwood would explore further in future efforts, most notably on some of the songs he’d write for supergroup Blind Faith. The relatively spare and haunting arrangement features Winwood’s voice along with Mellotron strings and harpsichord. Toward the song’s end, Wood adds a bit of flute.

With its signature “Hey Joe” (Hendrix version)-inspired riff, “Dear Mr. Fantasy” would become the most well-known track from Mr. Fantasy, and one of the few songs to survive into the set list of later-era Traffic. Steve Winwood’s faraway vocal – placed deep into the mix by producer Jimmy Miller – paradoxically calls attention to itself. The song’s “chorus” is little more than a catchy series of harmonized vocalizations with a snaky guitar figure. A stinging and lengthy guitar solo takes center stage mid-song while the three-chord melody repeats under it. Winwood’s harmonica fills add to the song’s bluesy character.

A vaguely flamenco-influenced acoustic guitar figure (presaging Yes’ “Roundabout” by a good few years) opens “Dealer.” The combined effect of the guitar, Chris Wood’s woodwinds and Mellotron create an ambience redolent of Northern Africa. Harmonized vocals led by Dave Mason carry the tune into its spirited chorus. There’s a hypnotic air of mystery and danger to the tune, and the Mellotron figure in the breaks is particularly memorable. Also of note is the unusually busy bass guitar line that snakes throughout the song’s second half. Perhaps not coincidentally, the central riff from the Beatles “Day Tripper” is played on acoustic guitar, buried in the mix near the song’s fadeout.

Related: Cream, Britain’s other early supergroup

Real Indian instruments were in vogue in 1967, thanks to their use by the Beatles, Donovan and others. “Utterly Simple” is essentially a waltz built atop a melody played by plucked sitar and droning tambura. Dave Mason’s lead vocal—first sung, then spoken—is so deep into the mix as to be nearly imperceptible. Chris Wood adds a lovely counter melody near the song’s close.

Winwood reaches into his pliant upper vocal register for “Coloured Rain,” backed by an overdubbed sax section courtesy of Chris Wood. Here Wood brings out his R&B side, sounding not unlike Graham Bond (Wood and Bond would team up in 1970, albeit briefly, in Ginger Baker’s Airforce). Winwood’s soulful Hammond B3 organ is a highlight of the track, one with lyrics that split the difference between love song and psychedelic outing. The instrumental breaks in “Coloured Rain” represent the “heaviest” musical moments on Mr. Fantasy, with Wood’s saxes blowing wildly while the rest of the group lays down a mesmerizing rhythm. Capaldi’s often overlooked drumming is deft and forceful; even his insistent use of cowbell works in this context.

Dave Mason’s “Hope I Never Find Me There” is another example of the guitarist’s predilection, in 1967, at least, for writing pop songs with a light classical feel. In places, the song seems to lift characteristics from other tunes on Mr. Fantasy. The production choice of employing a phase shifter results in a song that could have only come from the late 1960s pop music scene.

Traffic’s debut album closes with “Giving to You.” The opening 30 seconds of the track are a mess, filled with dizzying instrumental and vocal crosstalk. Once that hazy audio collage subsides, what emerges is a snare drum- and flute-led tune that feels a bit like what Brian Auger’s Trinity would do (with organ) in 1968 and beyond. The instrumental tune features some fiery lead guitar work, followed by a jazzy, overdriven organ solo. “Giving to You” is less a song than a jam, but it’s a glorious, exciting one, and an uptempo way in which to close the musical grab-bag that is Mr. Fantasy. The cacophony that characterizes the song’s opening returns for the fadeout, closing—perhaps unintentionally pointing the way for future Traffic releases—with the word “jazz.”

As an album, Mr. Fantasy has a convoluted release history. Standard music industry practice in 1967, in Great Britain, at least, held that an artist’s singles and albums did not overlap; previously released hit singles were rarely appended to subsequent LP releases. This helps explain why neither “Strawberry Fields Forever” nor “Penny Lane” would appear on the Beatles’ 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. But shortly after coming together, Traffic would record and release three singles. Only one of these, “Coloured Rain” (the B-side to “Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush”) was included on the British LP upon its December 8, 1967, issue. The album version of “Giving to You” is a different mix and edit than its earlier monaural B-side release.

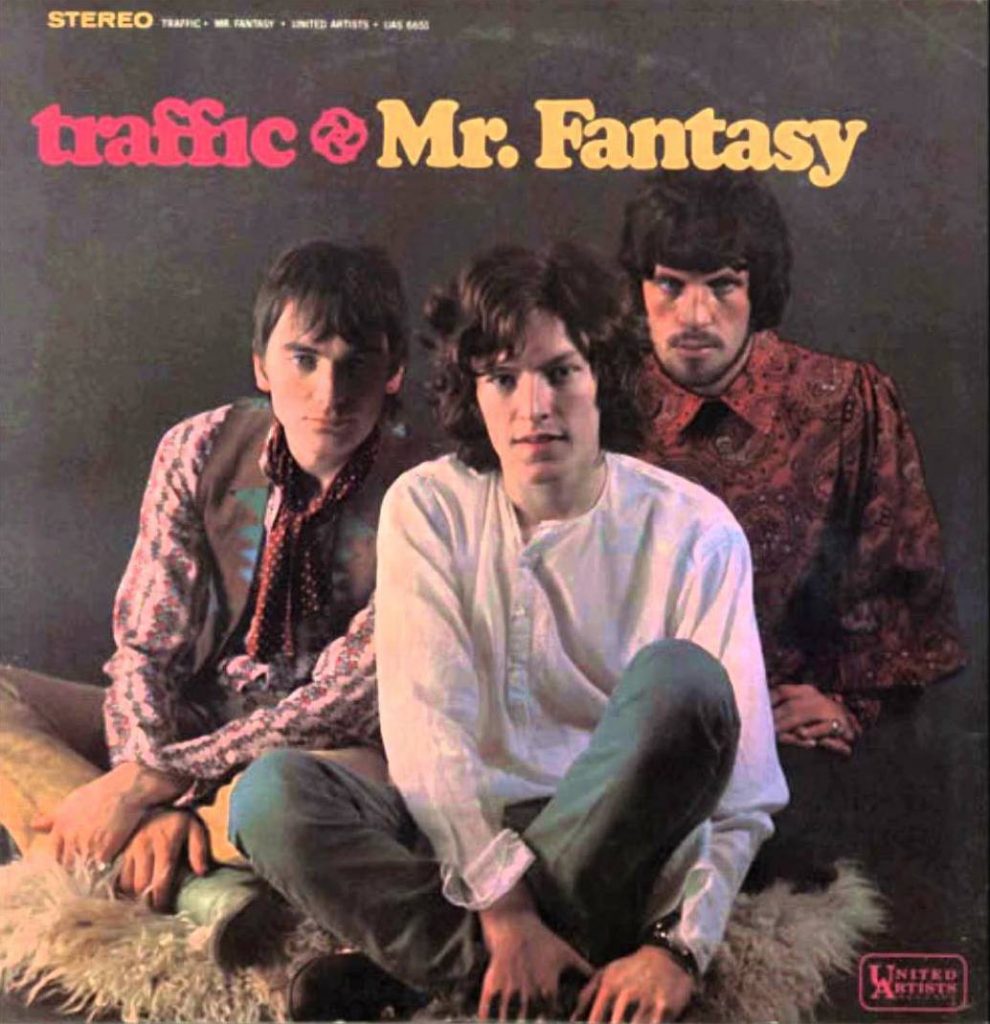

But by the time of the early January scheduled release of the album in the U.S., Mason had left the group (for the first of several times, perhaps unintentionally paving the way for keyboardist Rick Wakeman’s fractious relationship with Yes in the 1970s and beyond). United Artists dropped two of Mason’s solely composed songs and added three tracks previously only available as singles (“Paper Sun,” “Hole in My Shoe” and “Smiling Phases”).

Watch the “Paper Sun” video

That initial release was re-titled Heaven is in Your Mind, but it was quickly reissued as Mr. Fantasy, reaching #88 on the Billboard album chart (“Paper Sun” was the only single to chart in the U.S., peaking at #94). Both U.S. versions featured cover art that pointedly omitted Mason. Subsequent reissues in the CD era attempted to reconcile the differences and bring together non-album tracks from the period around the album’s original recording. In 1999 Mr. Fantasy was added to the Grammy Hall of Fame.

The album, and other Traffic classics, are available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Traffic perform the title track live in 1972

Related: Our Album Rewind of Traffic’s Low Spark of High Heeled Boys

Watch a mini-documentary about the album

6 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationFor those interested in this band, there is a biography of Chris Wood which also chronicles the story of Traffic in depth called ‘Tragic Magic, the Life of Traffic’s Chris Wood’. Available at the usual on-line outlets.

The duet vocal in “Heaven is in Your Mind” is Winwood/Capaldi, not Winwood/Mason and Jim Capaldi sings “Dealer” not Mason.

No mention of the UK mono release being vastly different from the UK stereo release , and both of those being different from the USA release? Really ? and a picky side note : I really doubt Rick Wakeman woke up one day saying to himself ” Oh thank dog Dave Mason has left Traffic several times . Im going to do that when I get into Yes ” .

LOL–that’s exactly what I thought when I read that reference to Rick Wakeman

Rather than being either “Hey Joe” inspired or trichordal, the underlying I-VIIb-IV-I chord progression of Mr. Fantasy is common to two iconic classics of 1968: “Sympathy for the Devil” and “Hey Jude.”

That mini-documentary utterly erases Dave Mason from the history of the band. There are hardly even any photos of him. The segment where Winwood looks at the gatefold photos (which include Mason) and remarks about “all” his friends being gone implies that Mason is dead too, definitely not the case (as of 2024).