Seatrain: 1 Band, 2 Spellings, 5 Lineups, 4 LPs in 4 Years on 3 Labels, 1 Legendary Producer, 13 Questions

by Jeff TamarkinTalk about a convoluted history: Few bands went through as many changes in as brief a period. In just four years, 1969-73, there were five different lineups, with more than 15 musicians claiming membership at one point or another. They mashed up several different styles and released four albums on three different labels, one of which—under the guidance of one of the most highly regarded producers in rock history—is still considered in some quarters a bona fide classic. They evolved out of the remnants of a fairly well known New York group, relocated to Northern California and ended up in Massachusetts. One member in particular came out of an early progressive rock band, later spent some time in the best-selling bluegrass band of all-time, and went on to enjoy a sustained solo career playing both electric and, mostly, acoustic music.

They were called Seatrain, Or, as it was spelled on their debut LP, Sea Train.

Watch Seatrain perform their biggest single, “13 Questions,” live

To unravel this jumbled-up chronology, one must start with the Blues Project, the New York band that included, at its 1966-67 peak, the great Al Kooper on keyboards and lead vocals, and guitarists/vocalists Steve Katz and Danny Kalb. That band also included the bassist Andy Kulberg (who also played flute) and drummer Roy Blumenfeld. When the Blues Project split in 1967, with Kooper and Katz founding Blood, Sweat and Tears and recording the sublime Child Is Father to the Man, Kulberg and Blumenfeld went in a different direction, putting down stakes in Marin County, California, just north of San Francisco. There they teamed up, in 1968, with guitarist/vocalist John Gregory (formerly of the local band the Mystery Trend), saxophonist/bassist Don Kretmar and violinist Richard Greene. The latter was a particularly versatile player who had already made a splash outside of the rock world as a member of Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys, the outfit that, for all intents and purposes, had birthed the bluegrass genre back in the early 1940s. Greene had also spent time with the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, one of the most significant of the acoustic folk revival groups of the early ’60s.

With such a diverse background, the new quintet was bound to conjure up something original and that is precisely what they did. Heading into a Berkeley, California, recording studio, they cut 10 songs, both original compositions and a few covers (Jody Reynolds’ 1958 hit “Endless Sleep” and two soul nuggets, James Ray’s “If You Gotta Make a Fool of Somebody” and the obscure early Motown number “Mojo Hannah”). The new group called the album Planned Obsolescence and, as Blumenfeld and Kulberg owed Verve Records one more album, released it under the Blues Project name. Following that, the Blues Project carried on for another couple of years with mostly new personnel, but that went nowhere. The classic ’66-’67 lineup reunited in 1973 to release the live Reunion in Central Park album, but that was the end of that (until years later, but that’s another story).

Which meant that Kulberg and Blumenfeld and their new outfit were now free to pursue whatever sounds they wanted, and to find a new label and—this is where the twisted chronology really starts to knot up—to take on a new name. In 1969, the same five members signed with A&M Records and became, for a minute, Sea Train—two words. With eight songs, all written by various band members with lyrics provided by Jim Roberts (who’d also helped out on a couple of the Planned Obsolescence tunes), the newly christened quintet self-produced the recording and called upon A&M staff member Henry Lewy (who had once worked on the Chipmunks’ novelty hits, as well as the Mamas and the Papas, Leon Russell and others) to serve as engineer. (Lewy would later move on to more prestigious clients, including Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and Leonard Cohen.)

Self-titling the album Sea Train, the band made a point of demonstrating its versatility, seamlessly mixing a modified jazz fusion sound with elements of Greene’s bluegrass past and the rock that Kulberg, Blumenfeld and Gregory had worked with in their previous bands. Despite having some worthy moments, the album promptly tanked, however, not even coming close to the Billboard top 100, and before 1969 was out, the band had begun to splinter, with Blumenfeld leaving, along with co-founder Gregory. Greene, Kulberg and Kretmar stuck around, and three other players were brought in—vocalist Red Shepherd, guitarist Elliot Randall and drummer Billy Williams—but that aggregation didn’t even stay together long enough to make an album.

Listen to the self-titled opening track from the self-titled debut album

Which, it turned out, was probably the best thing to happen to Seatrain (now a single word). Survivors Greene and Kulberg were soon joined by three new recruits—keyboardist/vocalist Lloyd Baskin, a veteran of New Jersey, Boston and upstate New York soul-rock bands; drummer Larry Atamanuik; and guitarist/vocalist Peter Rowan—who were well-positioned to lift Seatrain up to a more prominent position. A&M Records let the group know that it was no longer interested, but Capitol was.

And Capitol, it seemed, had ties to a producer that the label felt might be able to bring out the best in the reconstituted band. This fellow, an Englishman, had done well with his last clients, but it seems that they had recently gone their separate ways. This producer was looking for something else to sink his professional teeth into, and so it was that Seatrain, despite having no track record to speak of, headed over to London’s AIR Studios, where co-owner George Martin got to work on his first post-Beatles project. It would become Seatrain’s most lauded—and most successful—album.

Calling it, simply, Seatrain, the second proper album by the band consisted of 11 songs, mostly originals, although the opening track and the last three were covers. That opener went a long way toward convincing listeners that there was something there. Written by Lowell George, a recent alumnus of Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention and the co-leader of the new, Southern California-based band Little Feat, “Willin’” was the song that caused Zappa to suggest to George that he’d be better off forming his own group. It appeared on the 1971 Little Feat debut as a slowish ballad, but Seatrain (which retitled the song “I’m Willin’”) sped up the tempo and went wild with it, allowing Rowan—who split lead vocal duties with Baskin throughout most of the album—to exercise the vocal calisthenics he had displayed as the lead vocalist in Bill Monroe’s group and in the 1967-69 Elektra Records art-rock band Earth Opera, which had also featured the whiz-kid mandolinist David Grisman. With Greene’s fiddle powering the backing track, Rowan and Seatrain turned George’s truck-driving saga of “weed, whites [speed–ed.] and wine” into a celebration and set the tone for the rest of the album, which maintained that high quality throughout.

Seatrain was an album filled with highlights. Both “Song of Job,” which turned the biblical tale inside out, and “Broken Morning” were co-written by Kulberg and Roberts and given feisty, uptempo arrangements here, but again it fell to Rowan to take the music to a higher place. “Home to You” is a song he had written for Earth Opera (it opened their excellent second and final album, The Great American Eagle Tragedy). The Seatrain arrangement is dramatic and glorious, elevating the song of longing beyond the clichés that too often marred similar I-miss-you songs. “It’s tired and I’m getting late,” goes the attention-getting first line, already suggesting that this is something different, and by the time it gets to the chorus—“The truth, the lies and the alibis/Every sweet good day we do and die”—Rowan’s lyrical acuity, his careful word choices and the absence of fluff, have let us know that he is a songwriter of significance, something that will continue to be apparent for the next several decades as he moved on.

“Out Where the Hills,” another Kulberg/Roberts composition, had previously appeared on the Sea Train debut, where it too had exhibited a peculiar spelling: “Outwear…” The redone version here is much funkier, and Baskin’s lead vocal is superb, one of his best on the album. Rowan’s next showcase, “Waiting for Elijah,” would seem to mark a return to biblical imagery except that there isn’t any, despite the name of its focal character. Rowan’s vocal is both honeyed and bold, and the harmonies, as well as Baskin’s assured piano solo, turn the song into one of the album’s most memorable.

The next tune, however, is undoubtedly one of the best known Seatrain numbers of all: “13 Questions,” written by Kulberg and Roberts, gave the band its only brush with success on the singles charts, peaking at #49 in 1971. Despite that modest placement, the saga that begins with a visit (“Deep in the darkest hour of a very heavy week/Three Earthmen did confront me and I could hardly speak”) ultimately leaves the 13 questions (“each an endless hole,” the lyrics inform us) unanswered, but the song became a staple on FM rock radio at the time. The funky rocker makes one wonder why Baskin has largely been forgotten in the decades since his brief tenure with this band.

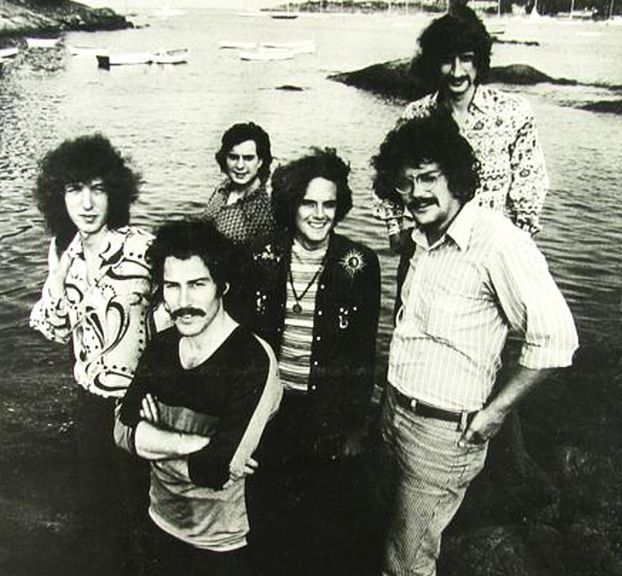

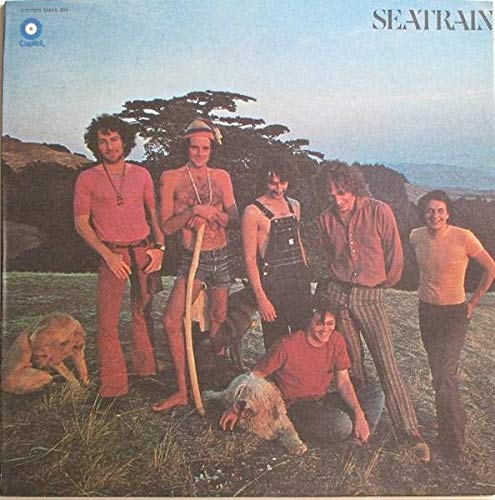

Seatrain, in an early ’70s band publicity photo (Peter Rowan in center with striped shirt, Richard Greene at far left, Andy Kulberg upper right)

Next up was Rowan’s “Oh My Love,” a good-time, uptempo, country-infused tune that hinted at where he would go musically during the just-dawning decade, and also drew upon his considerable yodeling skills, not exactly something that was heard in a lot of early ’70s rock.

Related: The year 1971 in rock music

Speaking of country, the traditional “Sally Goodin’” was a pure old-timey mountain fiddle tune and a dedicated showcase for the talents of Greene, who arranged it. The bluesy “Creepin’ Midnight,” one of the most obscure Gerry Goffin-Carole King compositions, occupied the penultimate position on the album, before Seatrain wrapped with yet another classic fiddle tune, “Orange Blossom Special,” taken here at a breakneck pace, one of the hardest rocking tunes on this close-to-perfect album.

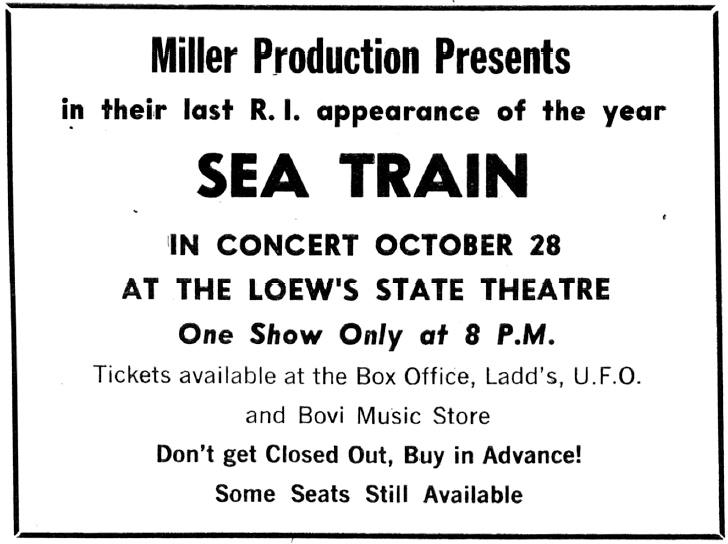

Seatrain didn’t exactly tear up the album charts, peaking at #48, but it did get enough radio and music press exposure that the band was able to perform at concert halls and festivals regularly. With the same quintet lineup, Seatrain went back into the studio in 1971, this time in Marblehead, Massachusetts, and cut a followup that basically maintained the same formula. They even rehired George Martin to produce, albeit not as successfully. Titling the album The Marblehead Messenger, the group stayed away from covers with this one, completing 10 songs written mostly by Kulberg-Roberts or Rowan, with one, the album finale, cleverly titled “Despair Tire,” bearing a Greene-Kulberg-Roberts authorship.

Although the album was solid, it lacked the originality and fire of its predecessor, and only one song, Rowan’s gorgeous “Mississippi Moon,” was a true standout. So much of one, in fact, that Jerry Garcia cut a version of it on his self-titled 1974 album and returned to it often throughout his musical ventures outside of the Grateful Dead.

Rowan and Garcia would, in fact, soon find that they had a lot to say to one another. When The Marblehead Messenger failed to gain much traction, stalling at #91, both Rowan and Greene bailed from Seatrain, as did drummer Atamanuik. Rowan and Greene chose to re-explore their bluegrass roots in a short-lived acoustic supergroup called Muleskinner, which also included mandolinist Grisman, former Byrds guitarist Clarence White, banjoist Bill Keith and standup bassist John Kahn. Bassist Stuart Schulman and drummer John Guerin were also involved in that outfit’s sole, self-titled album, released in 1973. Muleskinner came to a quick demise with the untimely death of White—felled by a drunken driver—but Rowan, Grisman and Kahn would quickly regroup, this time with Garcia, who’d begun his musical career in the early ’60s playing folk and bluegrass music, on banjo, and the great fiddler Vassar Clements filling out the lineup. Calling themselves Old and in the Way, they, too, released only one album during their brief lifespan, which bumped into the charts at #99 in 1975 but maintained a position as everyone’s must-have bluegrass album, ultimately becoming the best-selling album of all-time in that genre.

As for Seatrain, the band wasn’t quite finished yet when Rowan and Greene departed. In 1973, one last-gasp LP, titled Watch, found Baskin, Kulberg (now the only original member still involved) and lyricist Roberts giving it one more try, accompanied by Bill Elliot (keyboards, accordion), Peter Walsh (guitar, bass, vocals) and Julio Coronado (drums), plus a slew of session musicians. Not a terrible record by any means, Watch—produced by jazz bassist/cellist Buell Neidlinger and released by Warner Bros. Records—bore little resemblance to Seatrain at their peak just a couple of years earlier, although the best things on it were the band’s cover of Bob Dylan’s “Watching the River Flow” and Kulberg’s speeded-up remake of the Al Kooper-penned “Flute Thing,” his star turn with the Blues Project several years earlier. Watch made no noticeable commercial impact, missing the Billboard chart completely, and Seatrain chugged away into the history books.

Of the core members, Kulberg went into TV and film scoring, and died in 2002 of lymphoma. Atamanuik contributed to albums by folks like Emmylou Harris, Tony Rice, Linda Ronstadt and John Prine. Baskin, surprisingly, didn’t have much of a presence on recordings post-Seatrain, turning up on albums by the band Orphan, comedian-musician Martin Mull and a handful of others. Greene remained prolific, releasing a number of solo albums and contributing to releases by the likes of James Taylor, Maria Muldaur, Loggins and Messina, Melanie, the Blasters and Rod Stewart, among many others.

But it was Peter Rowan who arguably became the group’s most prominent ex-member. Following the dissolution of Old and in the Way, Rowan hooked up with his siblings, Chris and Lorin Rowan, who were working as a duo cleverly named the Rowan Brothers, recording a debut album with that configuration for Columbia. The addition of Peter undeniably gave the act more robust vocal harmonies and better songs, and together they released a trio of fine albums for Elektra and Asylum in the mid-’70s. Peter then set out on his own, cutting duo projects with Rice, Greene and Flaco Jiménez, as well as numerous solo albums and further collaborative projects. While most fit snugly into bluegrass or related genres, he also flirted with reggae, country and other styles, mostly using acoustic instrumentation and always showcasing that soaring tenor that remains a marvel even in his 80s.

Seatrain, sad to say, has largely been forgotten by most of those who still celebrate the classic rock of the early ’70s, but they are a band well worth a revisit, especially the two George Martin-produced titles.

Why did Seatrain fail to catch on in a big way, despite the band’s massive, innate talent and penchant for diversity? Quite possibly those attributes are what kept them down. With so many different musicians coming and going, so many different styles incorporated and the moves from one label to another to another, it was nearly impossible for Seatrain to establish a band identity—and for them to be promoted properly. Even the involvement of one of the world’s most celebrated producers didn’t seem to elevate the band’s commercial prospects.

Why, why, why? There are so many unanswered questions and what-might-have-beens—each an endless hole. [Not surprisingly, only some of their recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Watch a complete half-hour Seatrain concert from Copenhagen, 1971

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationWe all have that album that shoulda coulda woulda, but never did. Mine was Jim Krueger’s album from the late 70s, “Sweet Salvation”. Not too far away from Beck’s Blow by Blow/Wired. Although Jim did sing some, being the composer for “We Just Disagree”. Great supporting cast as well.

Seatrain released Lowell George’s tune (as “I’m Willin'”) before Little Feat did.