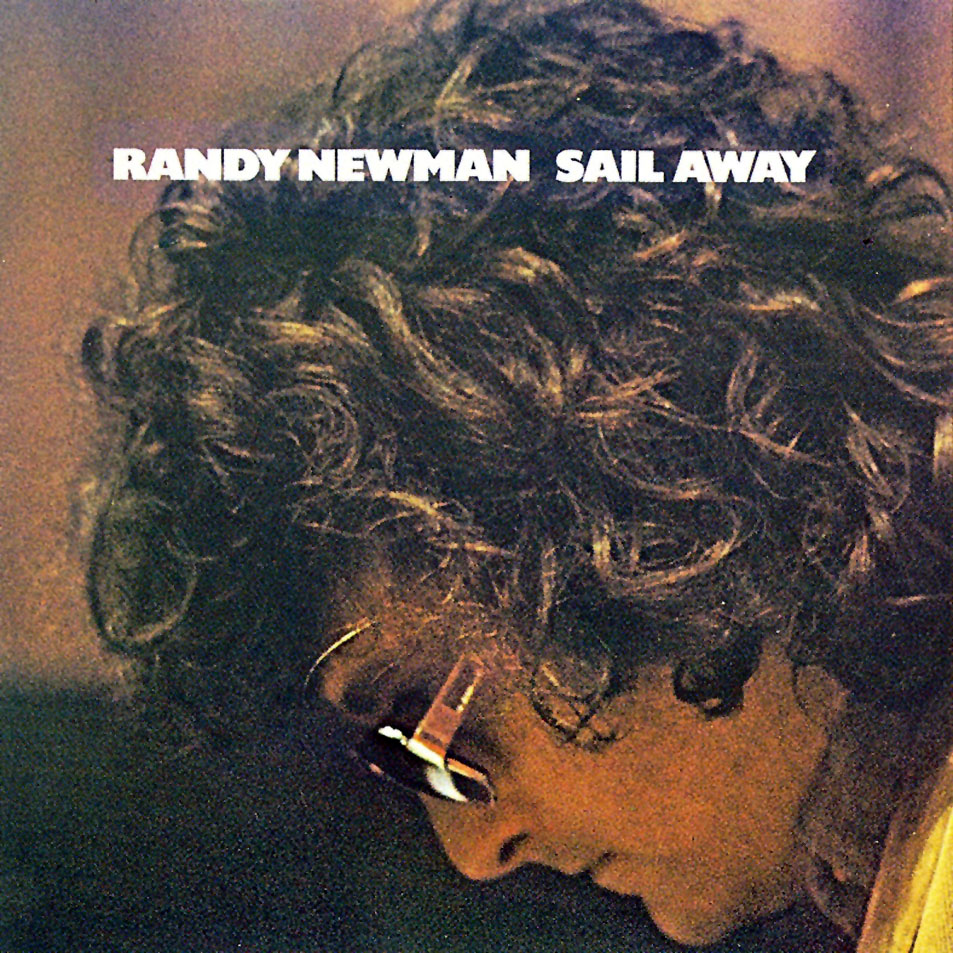

In late 1971, as Randy Newman and his producers Lenny Waronker and Russ Titelman contemplated recording his third studio album, eventually titled Sail Away, they were confronted with the reality that so far Newman’s tenure on Reprise Records had been commercially underwhelming. Born on Nov. 28, 1943, and a professional songwriter in his teens, he’d penned hits for a variety of performers, but his rather unusual voice, which some unkind critics likened to a frog’s croak, had limited his own recordings to publishing demos and a flop commercial single. Still, Reprise thought he had potential as a solo performer.

In late 1971, as Randy Newman and his producers Lenny Waronker and Russ Titelman contemplated recording his third studio album, eventually titled Sail Away, they were confronted with the reality that so far Newman’s tenure on Reprise Records had been commercially underwhelming. Born on Nov. 28, 1943, and a professional songwriter in his teens, he’d penned hits for a variety of performers, but his rather unusual voice, which some unkind critics likened to a frog’s croak, had limited his own recordings to publishing demos and a flop commercial single. Still, Reprise thought he had potential as a solo performer.

His first album, Randy Newman (1968), sometimes known under the aspirational title Randy Newman Creates Something New Under the Sun because of a headline on the original back cover artwork, featured complex orchestrations, inspired by “the family curse” of film scoring (uncles Alfred, Lionel and Emil were all familiar with Academy Award nominations and wins, as Randy himself would someday be). Randy Newman was full of pithy songs about family dysfunction, failed love affairs and depression (with a few queasy jokes thrown in). Reprise tried everything—including pleading advertisements which began, “Once you get used to it, his voice is really something”—but practically no one heard it beyond some dazzled music critics.

For the no more successful follow-up, 12 Songs, Newman used a band in place of orchestra, and as he later wrote, “Life in America went on.” A Reprise promotional disc sent to FM radio stations, Randy Newman Live, featuring just his voice and piano, became his third commercial release when it stirred some polite interest. “Then came Sail Away,” Newman wrote in the liner notes of a 2002 CD reissue, “in which I combined the three elements that made the earlier albums such failures.”

Newman’s constant tongue-in-cheek self-deprecation must somehow meet reality: Sail Away is a terrific album, and upon release on May 23, 1972, it proved a breakthrough for his career both in terms of quality and box-office appeal. And the songs—dealing with God, sex, death and a collection of shysters, deviants and fools—don’t compromise one iota with the marketplace. Instead, Newman audaciously expands what pop and rock music can deal with by committing 100 percent to his own dual cynical-romantic vision of history and modern life.

Related: The year 1972 in rock music

The title song, written in the magisterial key of Fmajor, was composed for a movie that was never made: Newman imagines a slave-trader laying out a line of disingenuous patter that is both humorous and creepy: “In America you’ll get food to eat/Won’t have to run through the jungle/And scuff up your feet/You’ll just sing about Jesus and drink wine all day/It’s great to be an American.” Newman has always acknowledged the song contains “all kinds of offensive things,” with the initial premise, that the slave trade was merely a matter of persuasion rather than criminality, being the most offensive. Satire this deep, especially with a rousing sing-along chorus of “Sail away, sail away/We will cross the mighty ocean into Charleston Bay,” should be impossible to pull off, but Newman manages it. We know which side he’s on, even when he’s singing in the voice of evil.

The orchestral arrangement of “Sail Away” is by Randy, but his uncle Emil conducts. Waronker, Titelman and their ace engineer Lee Herschberg place Newman’s unusual-but-expressive baritone in a beautiful sonic space, setting a tone for the entire album, whether recording a large orchestra or the stellar session musicians (guitarist Ry Cooder, drummers Earl Palmer and Jim Keltner, bassist Wilton Felder and Jimmy Bond, and percussionist Milt Holland among them).

“Lonely at the Top” was composed for Frank Sinatra, “if he had this sense of humor and if he actually was leaning against a lamppost, looking forlorn.” The song had debuted on Newman’s live album, recorded at the Bitter End in New York after midnight in front of a dozen nodding patrons—talk about irony in action! Newman seems to stifle a chuckle as he sings, “All the applause, all the parades/And all the money I have made/Oh, it’s lonely at the top/Listen all you fools out there/Go on and love me, I don’t care.” The clomping old-time-jazz arrangement is a wonder, revealing Newman’s love for both Fats Waller and Fats Domino.

“He Gives Us All His Love” is a deceptively simple gospel song, with the parody so deeply buried it might be mistaken for sincerity. (It was originally part of Newman’s score for the film Cold Turkey.) Does Newman really believe God “knows how hard we’re trying/He hears the babies crying/He sees the old folks dying/And he gives us all his love”? In “God’s Song,” which Newman places at the very end of the album, we meet a deity dismissive of people and their follies: “Man means nothing/He means less to me/Than the lowliest cactus flower. . ./How we laugh up here in heaven/At the prayers you offer me.” Part of the joke is that Newman sings as God, and the punchline comes with a rather sad depiction of love: “You all must be crazy to put your faith in me/That’s why I love mankind/You really need me.”

In “Old Man,” the subject gets even darker, if that’s possible. The slow tempo is funereal, and the strings play a melody worthy of Copland or Ives. Newman sings with a catch in his voice. The narrator, evidently a son who’s arrived just in advance of his father’s death, lays it out with grim directness: “Won’t be no God to comfort you/You taught me not to believe that lie/You don’t need anybody/Nobody needs you/Don’t cry old man, don’t cry/Everybody dies.”

Newman explained to journalist David Wild, “While I don’t have any belief in religion—far from it—I am interested in it. It’s a gigantic idea. It’s the biggest hit in history, the invention of God, because you know you’re going to die That’s my very clinical assessment of it.”

Another filial scenario comes in “Memo to My Son,” in which an adult struggles to advise an infant: “Wait’ll you learn how to talk, baby/I’ll show you how smart I am.” Unfortunately, the dad’s wisdom consists entirely of clichés, which Newman sequesters in the song’s bridge section. At barely two minutes, this is the type of comic miniature Newman excels at, and continues to write to this day, in between his weightier material.

An infectious, rolling rhythm nails down “You Can Leave Your Hat On,” which ultimately became one of Newman’s most-recorded songs, especially after Joe Cocker’s take was featured in the film 9 ½ Weeks. This perverse little gem has only minimal melodic development, and rhythmically it simply takes a Professor Longhair-type piano line, moves the accents around a bit, and turns it into a grinding striptease. Ry Cooder’s slide guitar is ghostly, Keltner’s drumming is virtuosic, and Newman sings the words in a faux-erotic style that suggests the protagonist is mostly bluster. In 2013 he told NPR he viewed the narrator as “a fairly weak fellow. To me, I would’ve thought the girl could break him in half.”

Sail Away features three older items from the Randy Newman songbook: “Simon Smith and the Amazing Dancing Bear,” which had been a hit for the English ex-Animals keyboardist Alan Price in 1967; “Dayton, Ohio—1903,” already recorded by Billy J. Kramer and Harry Nilsson; and “Last Night I Had a Dream,” which Newman himself issued with a different arrangement as a non-LP single in 1968. “Last Night I Had a Dream” is notable for its ominous atmosphere, including more excellent slide guitar from Cooder, and a dramatic series of changes in volume, tempo and density that make it a mini-movie. Newman might be playing with the idea that it’s inherently boring to tell someone else what you dreamed, unless maybe it’s all about them: “I saw a vampire/I saw a ghost/Everybody scared me/But you scared me the most.”

Two other standouts begin the second side of the original LP: “Political Science” and “Burn On.” Finished in October 1971 and debuted at a concert at UCLA’s Royce Hall, “Political Science” explores the limits of social satire as thoroughly as Newman’s most controversial songs, “Rednecks” and “Short People,” which were yet to come. “Political Science” is a brilliant example of how to humorously peel a lyrical onion, revealing information a little at a time to the listener.

The song begins with a speaker whose lecture topic is known to him but not immediately to us: “No one likes us—I don’t know why/We may not be perfect, but heaven knows we try.” Sounds reasonable? By the end of the first two verses, we discover the narrator’s frustration is quite advanced, and only extreme action—obliterating our enemies with nuclear weapons—can soothe his wounded national pride: “We give them money, but are they grateful?. . ./They don’t respect us, so let’s surprise them/We’ll drop the big one and pulverize them.”

“Political Science” is clearly influenced by the great Tom Lehrer, another singer-with-piano satirist who treated nuclear annihilation as a sick joke in songs like “Wernher von Braun” and “We Will All Go Together When We Go.” Newman’s melody is jaunty, suitable for any cocktail lounge, as he sings his narrator’s wacky justification for destroying most of the planet: “Asia’s crowded and Europe’s too old/Africa is far too hot/And Canada’s too cold/And South America stole our name.” Newman has said the speaker is “obviously a loon” but admits audiences don’t always get the point, saying, “There have been little glimmers of seriousness out there, like ‘Yeah, that wouldn’t be bad.’”

In contrast, “Burn On” sounds like a work of imagination but turns out to be simple reportage—the dangerously polluted Cuyahoga River in Cleveland did famously catch fire on June 22, 1969. In fact, oil slicks on the river had been burning with some regularity for years. But Newman’s eyewitness would like to turn this disaster into a celebration of “Cleveland, city of light, city of magic,” leading a rousing chorus of “Burn on, big river, burn on!” At least he pins the pollution on local officials, admitting to his beloved waterway, “The Lord can make you tumble/And the Lord can make you turn/And the Lord can make you overflow/But the Lord can’t make you burn.” Newman supplies the tale with a tinkling piano theme, overlaid with another spectacular orchestral part that one of his uncles might have fit into a John Ford western. Emil Newman again does the honors conducting “Burn On.”

Sail Away got no higher than #163 on the Billboard album chart, but it did help bump up Newman’s appearances from clubs to auditoriums, and often appears on “best albums of all time” lists. Newman himself downplayed its quality to Wild, saying, “Nothing I’ve ever done was intended to be art for art’s sake. I always thought lots of people could like what I was doing if they heard it. I always wanted to sell records.”

Singers of many genres competed to record its tunes, with “Sail Away” getting versions by Ray Charles, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Linda Ronstadt, Frankie Miller, Etta James and Dave Matthews, who tried it on live in 2008. The expanded CD version of the album on Rhino includes several interesting alternate versions, and two songs that didn’t make the cut, “Let It Shine,” written as a “happy and optimistic” tune for a TV pilot, and the rejected studio version of the very short sex farce “Maybe I’m Doing It Wrong,” previously heard on Randy Newman Live.

Randy Newman’s commercial breakthrough had to wait for his follow-up masterpieces Good Old Boys and Little Criminals. Although he still issues solo albums, for decades he’s concentrated on film scoring (two wins out of 22 Academy Award nominations for Best Original Score or Best Original Song, and still counting). He’s received seven Grammys and three Emmys, and millions of children throughout the globe probably know him only as the composer of “You’ve Got a Friend In Me” and other ditties from the Toy Story films. When they’re ready for Sail Away, it’ll be waiting for them.

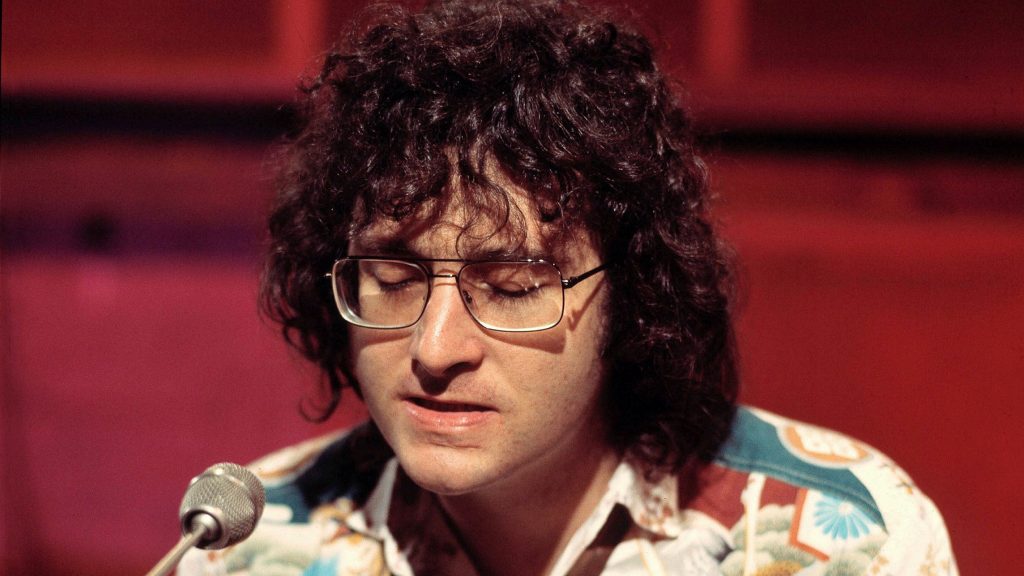

Watch Randy Newman perform “Political Science” live on the BBC’s The Old Grey Whistle Test in 1972

When Newman performs, tickets are available here and here. His recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationRandy’s appearance on SNL to do “Short People” was classic.

Nary a mention about the soundtrack for the motion picture “The Natural?”