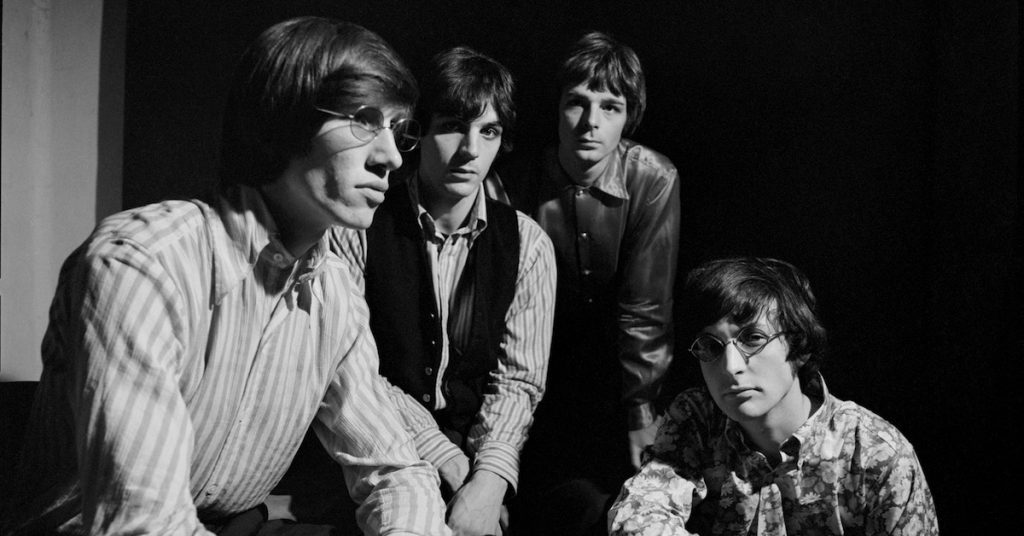

An early Pink Floyd promotional photo. L-R: Roger Waters, Syd Barrett, Richard Wright, Nick Mason (Photo: courtesy of Legacy Recordings)

Would people care about Syd Barrett—his star-crossed life, his music, his legacy—had Pink Floyd not gone on to become the mega-band it became without him?

Put another way: If there’d been no The Dark Side of the Moon, the album that broke the band in the U.S. in 1973, spending 741 weeks on Billboard’s top 200 from 1973-1988, would we be pondering Barrett still?

Of course not. (The band announced on April 6, 1968 that Barrett was no longer a member.)

Had the post-Barrett Floyd foundered, Barrett, born January 6, 1946, would have been seen as that mad, sad footnote of the psychedelic era in rock encyclopedias. Not the “crazy diamond,” the guy who “reached for the secret too soon,” the man “who cried for the moon,” the one Pink Floyd urged to “shine on” on 1975’s Wish You Were Here.

But Floyd hit the big time and we do care. There are copious amounts of pre-Dark Side music and video, some of it Barrett-related, or rooted, but much of it created after he’d been given the boot in 1968.

Barrett, who kept his English accent while singing (rare at the time), brought the band to dizzying heights in the U.K. with perverse topsy-turvy psychedelic English pop hits, “See Emily Play” and “Arnold Layne.” The latter song, Pink Floyd’s first single, concerns a crossdresser who likes to nick women’s undergarments off clotheslines and is admonished at the end with “Arnold Layne, don’t do it again!”

Watch the video for Pink Floyd’s first single, “See Emily Play”

The 21-year-old singer-songwriter-guitarist showed a flair for skewed genius, sometimes employing ominous nursery rhyme-lyrics with melodies that took unexpected twists and scrambled emotions.

“One of the great things in Barrett’s songs is that sense of potential,” singer-songwriter Robyn Hitchcock told Barrett biographer Rob Chapman. “It’s a sense of manic potential and by the end it’s a feeling of potential that’s gone … There’s a real feeling like an old man looking back with sadness. You know he’s resigned from life.”

Barrett had only one song, “Jugband Blues,” on the second album, one where Pink Floyd began exploring territory that became known as space-rock and prog-rock, with longer, less whimsical songs before ceding his turf. They sacked him for erratic behavior—Mental illness? Excessive drug use? Most likely a combination of both—barely one album into Floyd’s career, bringing in his friend David Gilmour to handle guitar and some vocals. Gilmour would share the writing with bassist-singer Roger Waters and, to a lesser extent, keyboardist Rick Wright and drummer Nick Mason.

Listen to Floyd’s “Jugband Blues”

I discovered Barrett, as I’m sure many of you did, post-Dark Side. It was really one of the primal joys of being a teenage rock fan in the ’70s, discovering a band “mid-career” or so and then working backwards. I bought A Nice Pair—the repackaging of Floyd’s debut The Piper at the Gates of Dawn and its follow-up A Saucerful of Secrets—a year or so after Dark Side and then the two Barrett solo imports, The Madcap Laughs and Barrett.

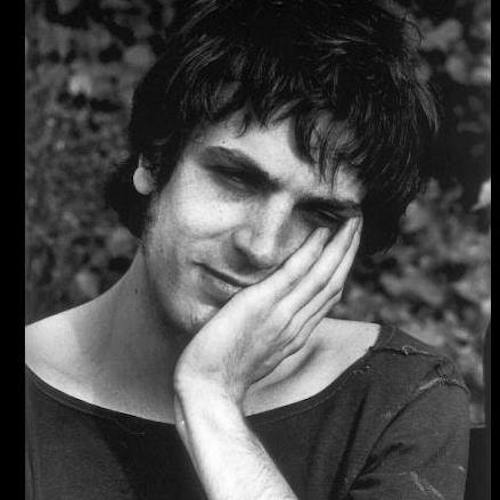

Syd Barrett (Photo from the Barrett Facebook page)

The surest path to legendary status in the pop music world is to create an extraordinary body of work in a short time and die young. Consider Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Nick Drake or Joy Division’s Ian Curtis. Their music had great impact, and it was posthumously heightened because they never grew old, faltered and faded away.

It was similar for Roger “Syd” Barrett—except he didn’t die young. A diabetic, he died at 60 on July 7, 2006, from pancreatic cancer, completely disconnected—and probably unaware—he’d been that handsome shining star of the psychedelic era, a fractured genius who was out of the business by age 25. He spent the next 35 years more or less in a downward spiral, as mental illness, likely exacerbated by youthful indulgence in LSD and Mandrax, took its toll.

Related: Pink Floyd postage stamps issued in the U.K.

Peter Jenner was the co-manager of Pink Floyd at the start of their career and when Barrett left he went with him. Jenner, who went on to manage the Clash and Billy Bragg (among others), told me this in 1990: “The pressures which hit him were the pressures from going from just being another guy on the block to being the spokesman of your generation. Especially during the psychedelic thing, there was a lot of heavy messiah-ism going around.

“People would come up and ask him the meaning of life. That put a young person who’d just written a song and played a bit of guitar under enormous pressure. On top of that, if you’re being given a lot of acid and there’s some sort of latent confusion inside you … Syd cracked of it. Acid is a very nasty, powerful drug, much underestimated. If you’re latently insecure and paranoid, it makes you very insecure and paranoid. It was a sad case. He was a very handsome, lovely person who became very violent, very fat, the opposite of everything he was.”

Jenner produced some of Barrett’s post-Floyd solo work in 1968. Jenner saw Barrett last in 1983 when Barrett was applying for a passport and needed someone to testify to the authorities that he was indeed “Syd Barrett.” Jenner saw him for just a few minutes, with no substantial communication.

On Dark Side, Waters assumed the role of primary lyricist. His intent was to deal with the stress we all experience—the futility of the rat race, unfulfilled dreams, class strife—and wrap it up with a look at madness. “Brain Damage” was interpreted by many as the band’s comment on what happened to Barrett. Key line: “And when the band you’re in starts playing different tunes/I’ll see you on the dark side of the moon.” Barrett would play incomprehensibly near the end of his Pink Floyd days. “Dark side of the moon” was a metaphor for madness.

In 1993 I spoke to Gilmour about the 20th anniversary of Dark Side. He told me, “I don’t see that much of it as being about Syd, really. ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’ [on Wish You Were Here] is specifically about Syd. Everything else has to do with Roger, his life, other people’s lives and Syd, obviously, would come into that. I think most people have blown that out of proportion or read things into it that aren’t there. But obviously, he’s within all our consciousness.

“Syd was a close personal friend of mine, who I loved dearly. I haven’t seen him, but I have got one or two friends who do see him and, uh, he’s the same; he’s mentally ill. You can’t talk to him. Really … He’ll talk back to you, but it won’t make any sense, really, what he says.

“Most people have an illusion about what they think he is. Unfortunately, they’re wrong. The romantic talk of the madcap Syd Barrett writing songs and making music quietly on his own is, I’m afraid, a sad myth. He’s not really a human being anymore.”

Watch the promotional film for “Arnold Layne”

I was speaking with Floyd keyboardist Rick Wright in 1997 and asked, of course, what he knew about Barrett’s current condition and mental capacity. “It’s the same since he left the band back in ’68. Very sad. Now he’s in hospital; he’s diabetic, sad to say, and possibly going blind slowly. There’s not much more I can say. We were asked by his doctors not to be in touch—it reminds him of who he was and puts him in deep depression. They say there’s nothing you can do and you should not speak to him or see him. We respect his doctors.”

There were royalties to keep him solvent; Gilmour made sure that was taken care of. “Word is that he’s comfortably off,” Wright said. “He’s not suffering financially or emotionally. He’s generally happy in his own little world.”

Everything you hear (or see) on Pink Floyd: The Early Years 1965-1972 is what led up to The Dark Side of the Moon. Songs well known and barely known, discoveries like the gorgeous live-in-Montreux take on the eerie, majestic epic “Atom Heart Mother,” rare concert footage, tracks from the obscure movie soundtracks More and Zabriskie Point, often bypassed when people consider Floyd albums.

Barrett’s music remains whimsical and gleefully fractured, as he married frolicking nursery rhyme-like couplets with darker, explosive psychedelia. Post-Barrett Pink Floyd wrote some compact songs, but they let loose the explorative beast with songs like “Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun,” “Astronomy Domine,” “Interstellar Overdrive” and “Echoes.”

While successful in Britain, they were in no way superstars, so what you hear here is the work of a band on the precipice of massive success, built on the framework of their damaged one-time leader.

Floyd’s Early Years collection is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here. Their extensive catalog, including many expanded editions, is available here.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationwonder if any modern drugs if they were available back then.Would have helped.A friend of mine took acid almost every day for about a year and got lost in his mind too ..Sad to see .

“Astronomy Domine” was indeed penned by Barrett, although I agree I actually prefer their post-Barrett version that the Floyd “let loose with” more than the original…