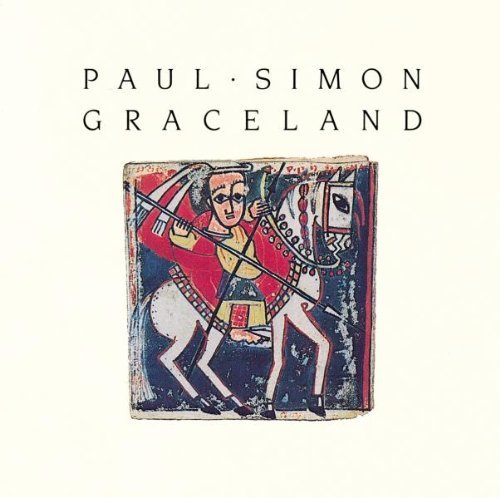

The genesis for Graceland, Paul Simon’s audacious 1986 comeback album, is the tale of a tape.

The genesis for Graceland, Paul Simon’s audacious 1986 comeback album, is the tale of a tape.

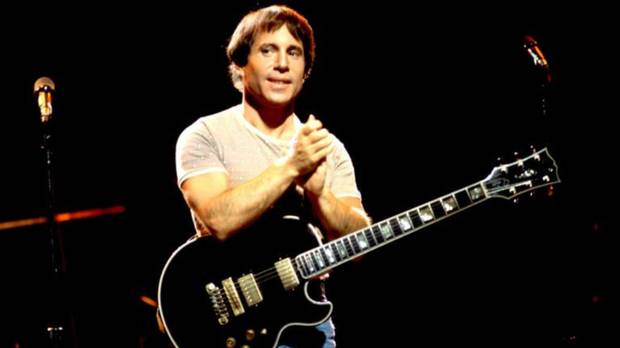

During the early months of 1984, Simon was nursing personal and professional wounds, his confidence battered by twin setbacks. Hearts and Bones, his second album since signing with Warner Bros. Records, had garnered the weakest sales and radio reception in 20 years despite some of his most ambitious and personal songs. His second marriage, to actress Carrie Fisher, had collapsed as he explored their volatile union in his music. A war baby older than his boomer fans, Simon was 42 and questioning his continued relevance, spending much of his time parked in his car smoking joints and listening to tapes as he watched workers build his new home in Montauk on Long Island’s eastern tip.

Turning to music as an escape, Simon found himself returning often to one cassette. Gumboots: Accordion Jive Hits Vol. II, a compilation of South African dance music, beguiled him with its distinctive synthesis of Western pop and jazz elements with African polyrhythms, its instrumentation of accordion, horns, guitars and percussion blurring musical borders, “sound[ing] vaguely like ’50s rock ’n’ roll out of the Atlantic Records school of simple three-chord pop hits,” as he would later observe in his Graceland liner notes. The cassette was a gift from Heidi Berg, a singer, songwriter and guitarist whom he had been mentoring, never guessing that the tape would instead push him into a new vector for his own music.

Until then, Simon’s music had evolved through early rock ’n’ roll, Brill Building pop and folk music as he explored literate lyrics and increasingly sophisticated harmonic and melodic instincts with selective detours, reggae, Latin, gospel and English and Andean folk music among them. His immersion into Gumboots’ gritty, exuberant mbaqanga “township jive” from the mean streets of Johannesburg’s Soweto district was broader, pulling him sharply toward rhythm as a key denominator. When he proposed exploring this new source with Warner Bros. chairman Mo Ostin and Lenny Waronker, they responded enthusiastically.

The two label execs recognized how world music influences were already reshaping Western pop and rock. Talking Heads had begun incorporating African rhythms at the end of the ’70s. Peter Gabriel challenged South Africa’s apartheid legacy on his solo albums. Reggae’s earlier inroads with rock fans opened a broader path to Africa’s musical diaspora, which had impacted Western pop periodically since mid-century when “Mbube” (Zulu for “lion”), a 1939 South African song written by Solomon Linda, mutated into “Wimoweh,” a surprising 1951 single hit for the Weavers that would resurface a decade later as “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” in the Tokens’ chart-topping doo-wop embellishment.

Related: Our Album Rewind of There Goes Rhymin’ Simon

The Gumboots tracks carried DNA from South African musicians inspired by American gospel and jazz in the ’50s and ’60s, led by Hugh Masekela, Abdullah Ibrahim (born Dollar Brand) and their peers excited by bebop. The early ’60s also brought international acclaim for Miriam Makeba, the South African singer, songwriter and lifelong activist canonized as “Mama Africa.”

Ostin and Waronker encouraged Simon’s deeper dive into world music and connected him to two crucial allies. Producer Hilton Rosenthal, who had helmed the Warner debut for Juluka, the integrated South African band, provided a vital resource in Johannesburg, while Roger Steffens had established an important showcase for Jamaican and African music on KCRW-FM, the influential Santa Monica college radio station. Between them, they would guide Simon to a broader array of West and South African music.

Rosenthal would also provide entrée to South Africa’s musicians and studios after dissuading Simon from licensing Gumboots material for use as an instrumental bed, as he had for Simon and Garfunkel’s “El Condor Pasa” years before. Arguing that the technical quality of the master tapes was beneath Simon’s standards, Rosenthal persuaded him to come to Johannesburg, where he could work with the Boyoyo Boys, the ensemble behind the specific track in question. The producer led Simon and engineer Roy Halee to Ovation Studios for new sessions.

Watch Simon perform “You Can Call Me Al” live at the Concert in Hyde Park

Rosenthal laid groundwork for the sessions by evangelizing the project to local musicians and mollifying some potential participants uneasy at the prospect of working with a white pop carpetbagger from the States. When Simon and Halee arrived in February 1985, they were delighted that the facilities lived up to Rosenthal’s state-of-the-art claims. The duo began assembling tracks designed as sketches, rather than finished songs. “I was very conscious of not wanting to repeat the mistake of Hearts and Bones,” Simon later told biographer Robert Hilburn. “I didn’t want to end up liking the songs but not the tracks. So, I decided to make sure I had a track that I liked, then I could focus on the song.”

Graceland’s songs thus began as sonic collages, capturing the foundations for songs that would be bicycled later to other studios for additional instrumentation and vocals. The Ovation sessions produced the basics for five of the album’s 10 songs, completed at New York’s Hit Factory and Los Angeles’ Amigo Studios with London’s Abbey Road and Master-Trak Enterprises in Crowley, Louisiana, also utilized. Less obviously, the Johannesburg sessions brought Simon a core team of musical partners including guitarist Chikapa “Ray” Phiri, bassist Bakith Kumalo and drummers Isaac Mtshali and Vusi Kumalo, with whom he worked on subsequent sessions and onstage.

Simon’s layered approach heightened the material’s multicultural contrasts with its mixture of instrumental timbres and his impressionistic lyrics, exemplified in the album’s opening track and third single, “The Boy in the Bubble,” recorded with members of Tao Ea Matsekha (“Lion of Matsekha”), a group from Lesotho. A wheezing accordion and a crack of drum beats launch a bounding, bottom-heavy rhythm arrangement led by Bakith Kumalo’s electric bass, as Simon delivers a “long distance call” witnessing “the days of miracles and wonder” both awe-inspiring and ominous. Its verses offer glimpses of violence (“the bomb in the baby carriage was wired to the radio”), sci-fi futurism and deep space vistas in its view of Earth from “a distant constellation…dying in a corner of the sky,” as well as an eerily prescient vision of technological dystopia:

“These are the days of lasers in the jungle…

Staccato signals of constant information

A loose affiliation of millionaires

And billionaires…”

What might be heard today as digital prophecy was written nearly two decades before the rise of social media.

While sustaining forward momentum, the rhythm section’s polyrhythms are the album’s heartbeat, derived from the township jams that first drew Simon’s ear and dominate most of the arrangements, even when the producers have grafted strong contributions from Stateside musicians. Like “…Bubble,” “You Can Call Me Al” features Rob Mounsey’s synthesizer and Adrien Belew’s guitar synth, buttressed on the latter track by a crack New York rhythm section to provide a brassy energy that earned it pole position as the first single. Yet ultimately, it’s the core trio of Ray Phiri, Bakith Kumalo and Isaac Mtshali that brings the piece to jubilant life with a telepathic interplay.

How and where Simon heard parallels between the Third World sources he explored during pre-production and other idioms closer to home were key to the album’s evolution beyond mere emulation, with his lyric sensibility further fusing the finished songs. Such is the triumph of the title song, which unwraps the titular image through multiple meanings. Here, Phiri, Kumalo and drummer Vusi Kumalo are joined by Demola Adepoju from Nigerian singer-songwriter King Sunny Adé’s Afro-Beats on pedal steel guitar in a fleet arrangement that moves with liquid grace as Simon traces a journey, gradually transcending geography through his imagery:

“The Mississippi Delta was shining

Like a National guitar

I am following the river

Down the highway

Through the cradle of the Civil War

I’m going to Graceland…

In Memphis, Tennessee…”

Simon’s real-world coordinates elide into a spiritual equation framed by heartbreak, his traveling companion “nine years old…the child of my first marriage.” Lessons from love’s loss haunt the journey.

“…She said losing love

Is like a window in your heart

Everybody sees you’re blown apart

Everybody sees the wind blow…”

Grace itself becomes the destination for “poor boys and Pilgrims with families” and an object of faith that “we all will be received” illustrated in a fanciful aside—the “girl in New York City who calls herself the human trampoline,” whose “tumbling in turmoil” he interprets as “we’re bouncing into Graceland.” With heartbreak and hope in melancholy equilibrium, “Graceland” becomes a secular hymn highlighted by its chiming pedal steel and electric guitar motifs and evocative background vocals from the Everly Brothers, the boyhood idols he shared with Art Garfunkel.

Simon’s reliance on South African musicians rewired his own guitar playing with their nimble interplay, a feature he adopted for subsequent touring bands and studio work, while the South African vocal styles he encountered provided further musical color. On “I Know What I Know,” the backing cries of another Gumboots group, General M.D. Shirinda and the Gaza Sisters, add a half-mocking, half-mourning accent to a deadpan account of a flirtation.

More substantial and ultimately consequential for Simon and the album was Roger Steffens’ introduction to Ladysmith Black Mambazo, a choral group, rooted in South Africa’s isicathamiya and mbube Zulu a cappella styles, which they would export to wider audiences in the wake of Graceland’s success. In founder Joseph Shabalala, Simon found a deep musical connection. Shabalala, meanwhile, found an enduring champion in Simon, whose abiding love for doo-wop and gospel harmonizing made Ladysmith’s sound irresistible.

Related: Our review of Simon’s latest release, 2023’s Seven Psalms

Simon’s collaboration with the troupe on “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” was a late addition to the album that produced one of its most luminous moments. Ladysmith opens the song with a hushed a cappella intro sung in Zulu before Simon enters to recount the romance between the rich girl of the title and a poor boy “empty as a pocket.” With the second verse, the song shifts up tempo as Simon and the trio of Phiri, Kumalo and Mtshali launches a percolating groove decorated with horns and percussion.

Simon ‘s bond with Shabalala was immediate and lasting. The songwriter decided to create an a cappella piece that would spotlight Ladysmith’s elegant singing, inviting Shabalala to collaborate on both music and lyrics, with Simon reworking lyric imagery from an early draft of “The Boy in the Bubble” and Shabalala responding with additional lyrics in Zulu. The song’s opening line—“Homeless, homeless, moonlight sleeping on a midnight lake”—casts its own lingering image over the troupe’s tender, mournful performance.

The lyrics to “Homeless” typify how Simon’s songs for Graceland would resonate poetically with African politics and culture while eluding direct references. While leaving him open to sniping over his avoidance of apartheid as a concrete topic, Simon’s more oblique approach was consistent with his careful balancing act as a lyricist, projecting his liberal social values while sidestepping citations of specific events or actors.

“Under African Skies” thus serves as the album’s most explicit reference to the continent that so broadly shaped its music and unfolds as a gracious and grateful tribute to that influence and Africa itself. “This is the story of how we begin to remember,” Simon sings, invoking “the roots of rhythm,” while Linda Ronstadt adds her harmonies in a cameo that would draw protest over an earlier concert booking in Sun City, the South African resort targeted by anti-apartheid activists.

Watch Simon perform “Under African Skies” live at the African Concert with Miriam Makeba, 1987)

Given Simon’s thirst to find connections between the African styles that drew him into Graceland’s musical borderland and musical traditions closer to home, the album’s forays into Cajun zydeco and Tex-Mex idioms were comfortable extensions sharing accordion and horn accents as well as strong dance rhythms. On “That Was Your Mother,” Simon recruited Rockin’ Dopsie (accordionist Alton Rubin, Sr.) and the Twisters to power a frantic Cajun two-step as the set’s penultimate track.

On the album’s closer, “All Around the World or The Myth of Fingerprints,” Simon partnered with Los Lobos, whom Lenny Waronker had recommended for a collaboration that would leave lingering friction. The East L.A. roots rockers were nonplussed when they heard the finished version of the song, the album’s toughest rocker, and saw it credited solely to Simon after learning that he had shared songwriting credits with several of the South African musicians on other Graceland selections.

Released on August 25, 1986, Graceland would invite other subsequent controversies even as it went on to win two Grammys and sell over 14 million copies to become Paul Simon’s most successful solo release, despite roiling controversies over his defiance of an anti-apartheid boycott to record in South Africa. Debate over the fine line between appreciation, assimilation and appropriation would bubble around its adroit fusion of Western and world music elements, with naysaying American and British critics and musicians pitted against most of the South African musicians that played on the album and went on to tour with Simon, as well as next-gen indie musicians like Vampire Weekend that would absorb Simon’s African pop variants whole.

Graceland’s inventive synthesis of multicultural influences ultimately marked an inflection point in Simon’s approach that would lead him to explore Brazilian music on his next album, 1990’s The Rhythm of the Saints, and incorporate polyrhythms into intricate song structures as integral to his later solo work.

Watch Paul Simon sing “The Boy in the Bubble” live in 1987 at the African Concert

Simon’s extraordinary catalog is available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.