From the start of his career in the late ’60s, everything about Leslie West was larger than life. A plus-sized fellow, he had a guitar sound that matched—loud, fiery, fast and overpowering—and a voice that didn’t know the meaning of soft. When the history of heavy rock is traced today, it invariably points to him as one of the origin points—it was no accident that he called his band Mountain.

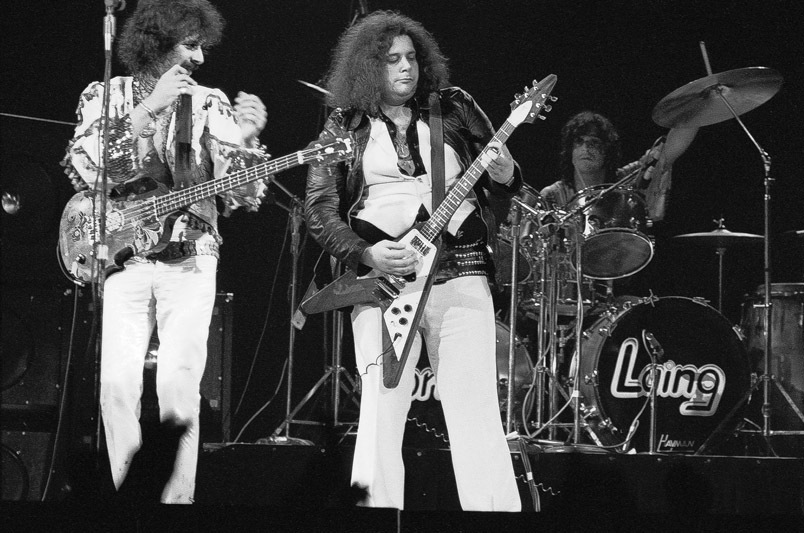

Born in New York City on October, 22, 1945, West grew up in New Jersey, Long Island and Queens and first gained local recognition in the NYC metro area with the Vagrants, who cut a version of Otis Redding’s “Respect” that failed to chart nationally (some woman named Aretha did a little better with it). From there, West teamed with Vagrants (and Cream) producer Felix Pappalardi to form Mountain, who managed to land a gig at the Woodstock Festival before most of the audience had a clue who they were. A series of classic albums and landmark gigs followed.

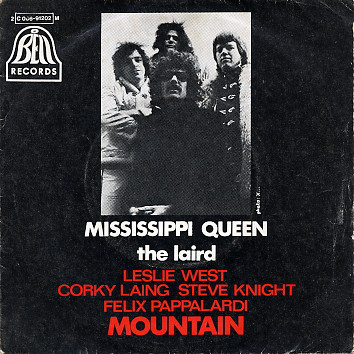

Above all else, they will always be remembered for “Mississippi Queen,” the blasting, cowbell-powered anthem—and #21 single—that was one of the highlights of their 1970 debut album, but to this day Mountain is revered by fans of primal heavy rock for their overall body of work.

Since the demise of Mountain, West maintained a steady solo career and also re-formed variations of the band. The hard rock guitar hero died in 2020 at age 75. We spoke with him about his career back in 2011 and 2013. The vast majority of these interviews (combined here into one) had never before been published.

The Vagrants were the house band at a joint on Long Island called the Action House. Do you remember it?

Leslie West: That was the only place that we could work regularly! I remember Billy Joel was with the Hassles, and there was a group called the Illusion, another called the Rich Kids. There weren’t that many groups.

True, but they all had the same blue-eyed soul style, including your band.

They were all trying to be like the Rascals, with the Hammond B-3 organ. That’s what we were trying to do. In those days, there weren’t that many places to play. When people say, “I remember the good old days,” if you really think back, maybe there were one or two days that were really great and the rest of them were like sh*t. How many days were really great? I was just learning how to play then—we were making rules up as we went along.

Listen to the Vagrants’ version of “Respect”

How did the Vagrants come to record Otis Redding’s “Respect”?

We went up to Atco, Atlantic Records, in [New York City], with my manager at the time. We rented the studio and while we were fooling around, Tom Dowd, the famous producer, walked in and heard us. He said to my manager, “What label are you guys on?” My manager said, “We’re not on a label,” and he said, “What’s the matter with Atco?” We turned around and said, “Nothing.” So, he signed us. Then when I recorded “Respect,” one day I go up to Atlantic, which was on 60th Street and Broadway at the time. I get out of the elevator—I was going to pick up copies of the single. Right in front of me is Otis Redding. I started sh*tting a brick. There he is in a sharkskin suit and I said, “Mr. Redding, this is my group’s single, ‘Respect.”’ He looked at it and he signed it, “To Leslie with respect.” I wish I still had it. But Atco signed us by freak. We didn’t have a label. We marched around Broadway, to the Brill Building, knocking on every door trying to get a record deal. You had a demo that you did for $49. It was almost like one of those booths where you record your voice. But this is a real studio, and at the time there were groups going around recording themselves and hopefully they could get a deal out of it. We pounded the pavement and luckily, or unluckily…

How did you go from there to Mountain? That was really quite a leap.

Atlantic assigned a producer to [the Vagrants], and the producer was Felix Pappalardi. He hadn’t produced Cream yet and I see this guy coming in and he looks like Sonny Bono, with the mustache and the scarf, and I say, “Who’s this f**king guy?” But we hit it off and he did two singles with us. One of them was “Beside the Sea” and the other was “Sunny Summer Rain.” “Beside the Sea” I think we did at Woodstock. A few years down the road, I don’t know how it came to be, but my manager got in touch with Felix’s partner and manager, who says, “Why don’t you go in the studio and see if you can do something with the Vagrants?” So we went in the studio. We didn’t have any songs. I thought, this is gonna be great, Felix will sit there with me and I’ll write songs with him. He said he had to go to England to finish recording Jack Bruce’s Songs For a Tailor. He says to me, “If you get something together, give me a call.” So I said, “We might have to break up but maybe that’s not the worst thing in the world.” I put together this group called Mountain with a jazz drummer and a keyboard player. He came back and heard it and he said, “It’s not gonna work.” He threw me out of the studio. I got another guy and went in the studio again and Felix heard it and he says, “This isn’t gonna work either.” So his partner finally said, “Why don’t you grab the bass and play with him?” That’s how it started.

You had already developed a signature guitar style by then.

Not yet. Maybe the style was just beginning there. I didn’t play that fast. I only used the first and the third finger on the fingering hand. So, I had to learn what I could do best my way so I worked on my tone all the time. I wanted to have the greatest, biggest tone and I wanted vibrato, like somebody who plays violin in a hundred-piece orchestra. It took me a while to get to the point where I said, “Yeah, that’s the sound I want to get every night.” It wasn’t that easy, just plugging in and going.

When do you feel you actually got there?

We were recording at the Record Plant. We’d just finished [the debut Mountain album] Mountain Climbing!, and Hendrix was in the other studio, Studio B, with Band of Gypsys. I knew that he wanted to maybe have Felix produce something. So Felix says, “Go in the next studio and ask Jimi to come in.” I said,“You want me to do it? I’m just a fat kid from Queens!” So, I walked in and I said, “Mr. Hendrix, Felix Pappalardi is next door and he’d like you to come and listen to our album.” He comes in and he heard “Never in My Life.” He hears the riff and he turns to me and says, “That’s some riff, man.” When I heard that come out of his mouth, you couldn’t talk to me. The funny thing is, Rolling Stone did an issue on Jimi Hendrix. One of the guys at work at the Record Plant was one of the Ramones. In the article, he says, “Jimi Hendrix was very shy. I remember him asking me, ‘Am I better than Leslie West?’” I have it framed in my living room now.

You were one of the first guitarists to play what was called “heavy” guitar at the time. How did you develop that sound?

I started listening to Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix and I said, “Whoa, I never heard anybody play the guitar like this.” A friend of mine, Waddy Wachtel, lived in the same building, in Forest Hills [Queens, New York]. He taught me how to play real guitar. I lived on one side of the building and he lived on the other. It was in Forest Hills Plaza, a brand-new high-rise. I’d hear a Beatles song come on the radio and I’d go down the elevator and run and take the elevator up to his house and by the time I got to his house, he already knew the song and he would teach it to me. He bought himself a George Harrison model Rickenbacker 12-string and he sold me his Les Paul Jr. That’s how I started playing that. He was the reason—we went to see the Beatles together and had some great times together.

Related: 10 seminal hard rock albums

Mountain was on Windfall Records. Who owned that?

That was [Mountain’s manager] Bud Prager and Felix Pappalardi’s label. Another screwing I took. Bud told me that when he met Felix he thought it was going to be a windfall for them. This was right before [Pappalardi] produced Cream. Whenever they used to tell me I was going to have a great year, I said, “If I’m having a great year you guys are having a ridiculous one.” Felix produced it, he was part manager and writer, a performer. He had it every which way you could go.

Mountain was still a brand-new band when you played Woodstock. Did the audience get what you were doing?

It was only our third or fourth show. I don’t know if they got what we were doing because to tell you the truth I was so nervous. You could see maybe 40 rows in front of you. We got to go on at a great time because Jimi Hendrix’s agent was our agent. Jimi was like the unofficial headliner of Woodstock. So, he must have said, “If you want Hendrix, you have to take this other group, Mountain.” They paid us $5,000 and we did get paid. What I remember the most, not from our set, was Sly and the Family Stone. We were on just before it got dark, after the Grateful Dead and Creedence came on, hit after hit after hit. I said, “How many freakin’ hits can a group have?” Then the Who came on and did Tommy and then Sly came on. That was the first time I saw people hold up a Bic lighter when they wanted you to come back for an encore. It was like candles. Now everybody says they were there. But if you ask them which night it rained they can’t remember. We called it Mudstock. We went on Saturday night but they lost our film so we weren’t in the movie.

Watch Mountain perform “Southbound Train” at Woodstock

I heard your manager wouldn’t sign off on the band appearing in the film.

That’s what I also heard. He probably didn’t get enough money—another stupid move we made. But [producer/engineer] Eddie Kramer called me and he found two tracks. They’re on the Woodstock boxed set [Woodstock: 40 Years On].

How did “Mississippi Queen” come about? You’d probably never seen the Mississippi River!

How did “Mississippi Queen” come about? You’d probably never seen the Mississippi River!

[Drummer] Corky Laing had this lyric and he came to my apartment in Manhattan. He says, “Look, I have this lyric, ‘Mississippi Queen.’” He said when he was in Nantucket and playing this bar and the power went out, he was just playing the drums and shouting the words “Mississippi Queen, do you know what I mean?” He’s watching this girl dance—this is what he says. So, I started fooling around with the guitar in the apartment and I came up with this riff and it’s three chords. We went really quickly into the studio and Felix told him to count it off and he counted it off with a cowbell. We left it in there. The only thing I don’t like is there’s a piano in there. I hated it. It was stupid for it to be in there. Needless to say, we don’t use a piano when we play it now.

The first time I heard Michael Jackson’s “Beat It,” I said this is the “Mississippi Queen” riff inverted.

It’s not, it’s “Never In My Life.” [Guitarist] Steve Lukather is the one who played that on “Beat It,” not Eddie Van Halen [who played the guitar solo]. I wanted to say something to Steve when he was in the studio that day.

Read part two of our interview with Leslie West here, featuring more about Mountain plus his solo career and some favorite live and studio jam sessions!

Watch Mountain perform “Mississippi Queen” live at Randall’s Island in New York City in 1970

Mountain’s recordings are available here.

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationGreat interview. I just posted it on The Leslie West & MOUNTAIN Fan Club Facebook Page. Check it out!

Thanks so much!

I got to interview Felix Pappalairdi twice and got a phone call from him as well. He was a musician’s musician. Lot of music know-how.

After hearing Leslie, I bought two Full Marshall Stacks and put them in my bedroom. Mom was not amused, go figure!