Jefferson Airplane ‘Surrealistic Pillow’: The LP That Fed Your Head

by Mark Leviton Listening to the 1967 landmark Jefferson Airplane album Surrealistic Pillow can be a confusing experience. At times it seems to be music from a group put together by committee, one especially confused about how to achieve the proper band chemistry, stylistic coherence or commercial appeal. It ricochets from genre to genre, either a sign of eclectic inclusivity and virtuosity, or a lack of firm direction. It sounds like a sonic experiment, drenched in echo and reverb, with poetic lyrics that often flirt with the totally irrational. And yet it was recorded in a corporate recording studio and appeared on perhaps the un-hippest major American label of the period, RCA. Despite everything, Surrealistic Pillow is a masterpiece, one of the seminal LPs of the “Summer of Love” or any other period.

Listening to the 1967 landmark Jefferson Airplane album Surrealistic Pillow can be a confusing experience. At times it seems to be music from a group put together by committee, one especially confused about how to achieve the proper band chemistry, stylistic coherence or commercial appeal. It ricochets from genre to genre, either a sign of eclectic inclusivity and virtuosity, or a lack of firm direction. It sounds like a sonic experiment, drenched in echo and reverb, with poetic lyrics that often flirt with the totally irrational. And yet it was recorded in a corporate recording studio and appeared on perhaps the un-hippest major American label of the period, RCA. Despite everything, Surrealistic Pillow is a masterpiece, one of the seminal LPs of the “Summer of Love” or any other period.

Lead singer Marty Balin put the group together in 1965 in San Francisco, tweaking its personnel several times before sessions for their second album, Surrealistic Pillow, began on Halloween 1966 in RCA’s Los Angeles studios, under the supervision of staff producer Rick Jarrard and engineer Dave Hassinger. (The story of the band is brilliantly told by Best Classic Bands’ editor Jeff Tamarkin in his book Got A Revolution! The Turbulent Flight of Jefferson Airplane.) Balin was as comfortable sneering incomprehensible Dada-esque rock lyrics as he was crooning ballads that could fit into a mainstream Broadway show, and seemingly never met a change of tempo he didn’t like. Co-lead singer Grace Slick exuded sex appeal, injecting her operatic contralto with plenty of vibrato, enunciating every word with a biting precision, and suggesting somehow that the whole thing was a put-on, not to be taken too seriously. Ditching her previous band the Great Society and importing two songs she used to sing with them, “White Rabbit” and “Someone to Love” [sic], Slick replaced Jefferson Airplane’s original female singer Signe Anderson shortly before the new RCA sessions.

Watch the Airplane perform “Somebody to Love,” an outtake from the Monterey Pop documentary film, in 1967

Drummer Spencer Dryden—a jazz nut who could recreate solos by Gene Krupa and Baby Dodds hit-for-hit—was also new to the band, replacing the unstable genius Alexander “Skip” Spence, who went on to found Moby Grape before experiencing a psychic implosion. Guitarist Jorma Kaukonen was obsessed with recreating the acoustic fingerpicking of Reverend Gary Davis, but had also developed his own unique electric guitar style, which involved a lot of stabbing and sizzling notes and dense chords. He’d brought in his old buddy Jack Casady from Washington, D.C., a guitarist-turned-bass-player who worshipped James Brown’s mainstay Bernard Odum and Motown’s bass maestro James Jamerson. Also on board was Paul Kantner, a guitarist from the Bay Area folk scene who loved the Kingston Trio and science fiction novels, and could sing in a gruff baritone when required. “Our voices together were a tag team kind of thing,” Slick told Tamarkin. “Marty would be singing and I’d do something else off the top of that and Paul would be somewhere else underneath. It was a little sloppy, actually, it wasn’t precise, but it was fun because you could do anything you wanted to.”

Also added to the Surrealistic Pillow secret sauce: the contributions of “musical and spiritual advisor Jerry Garcia,” radical politics, hits of Owsley LSD, perpetual litigation with fired manager Matthew Katz, and a generalized dislike for Rick Jarrard and RCA (which had spent a lot of money signing a band they didn’t understand but from which they expected great financial rewards).

The first songs recorded on Oct. 31, 1966, were “She Has Funny Cars” (the title “surreal nonsense” according to Balin), words by Balin and music by Kaukonen, and Skip Spence’s “My Best Friend,” which was destined to be the first (failed) single from the album before RCA got hip to the two huge hits Grace Slick had in her pocket. Dryden kicks off “She Has Funny Cars” with a Bo Diddley-ish tom-tom beat, then bass and guitar state the infectious riff and Marty enters aggressively with “Every day I try so hard to know your mind/and find out what’s inside you/Time goes on and I don’t know just where you are/or how I’m going to find you.” Kantner and Slick double Balin’s last two lines. But that rhythm doesn’t hold, yielding to a sort of Lovin’ Spoonful swing; the three singers interweave and Slick swoops around, interjecting exclamations and sometimes leaving words behind entirely. Before a fade, Casady’s fuzz bass rises to prominence, Kaukonen wails some brittle notes and Jefferson Airplane have succeeded in announcing their psychedelic musical credo in just a bit over three minutes.

“Somebody to Love” (as it was re-named) is next, written by Slick’s brother-in-law Darby Slick, but sped up considerably from its Great Society version. It went as high as #5 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart when released as a single in spring 1967. Grace Slick’s vocal jumps out and grabs the listener from the start. The backing is flawless, while also maintaining an off-kilter and barely-in-control vibe. Loud/soft dynamics are expertly controlled (Jarrard/Hassinger, take a bow). During the bridge, listen to what Slick does with the word “his” in “Your eyes/I say your eyes may look like his/But in your head, baby/I’m afraid you don’t know where it is.” Her work is as authoritative and powerful as any of the greats: Aretha Franklin, Tina Turner, Janis Joplin, Judy Garland, Edith Piaf, you name ’em.

After the quite lovely, beautifully arranged “My Best Friend,” Marty Balin has his own song of transcendence to match what Slick does on “Somebody to Love.” “Today” was written by Balin with Kantner, and it’s full of delicate yearning, articulated by Balin with astounding vocal control on every phrase. The electric guitar fills, tambourine, timpani-like drums and backing vocals all reverberate increasingly as the track continues, eventually reaching a Phil Spectorian flourish.

Jarrard defended his use of mega-reverb to Tamarkin, saying it was only one of the tools used to approximate a visual texture. “You’re painting a picture. A lot of artists think, I just want my voice up there, raw. They forget that when you’re onstage, you’ve got a lot of visual things going for you, but when you’re creating a record you have to replace those visuals and embellish.”

“Today” is one of the tracks on which guitarist Garcia is credited, although Jarrard insists he never met Garcia and he isn’t present on any recordings. But he must have been hanging around at some point: everyone in the band agrees Garcia named the disc by remarking “That’s as surrealistic as a pillow!” after hearing one playback. In his autobiography Been So Long, Kaukonen called Jarrard “brilliant” and said Garcia “was a combination arranger, musician and sage counsel,” but concluded he did not “produce” any tracks.

To drop such an unabashedly romantic love song as “Today” into the LP is audacious enough, but to up the ante by following it with “Comin’ Back to Me,” another hyperemotional Balin feature, is something like inspired lunacy. Written by Balin under the influence of some spectacularly strong marijuana, “Comin’ Back to Me” combines poetry (“The summer had inhaled and held its breath too long/The winter looked the same as if it had never gone”) and a Gregorian classical feel, with Slick playing the recorder. Balin is on acoustic guitar and Casady on bass (not everyone was in the studio when Balin was suddenly inspired to lay down the tracks shortly after having written the tune).

“3/5 of a Mile in 10 Seconds,” another headlong Balin killer, leads off the second LP side. With a title from the sports pages and hippie-protest lyrics (“Do away with people blowing my mind/Do away with people wasting my precious time/Take me to a circus tent where I can easily pay my rent/And all the other freaks will share my cares”), the track rocks like hell, Dryden and Kaukonen to the fore. There’s more doubling of Balin’s lead by Kanter and Slick, an Airplane trademark. Kaukonen reveals the influence of B. B. King, Ravi Shankar and John Coltrane in his careering electric solo, and Kantner’s rhythm guitar goes full Weir/Garcia.

“D.C.B.A-25” is a Kantner tune named after the number assigned to Albert Hoffman’s first LSD batch. It’s pretty standard folk-rock in the vein of Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, elevated mostly by Slick’s loose ’n’ groovy tandem vocal and Casady’s particularly active bass. Kantner sings better on the album’s only piece of outside material, Tom Mastin’s “How Do You Feel.” Both Jarrard and Kantner knew Mastin from their folkie days in the Bay Area Peninsula, and it’s a very The Mamas and the Papas-type performance, with choral vocals (including some “ba-ba-ba”s), half a dozen overdubbed acoustic and electric guitars, and Slick once again tooting on recorder.

Related: Remembering Marty Balin

Kaukonen’s two-minute instrumental “Embryonic Journey,” “the first song that I ever wrote,” sits comfortably at side two’s mid-point. Kaukonen had been messing around in the RCA studio on his Gibson J-50, fiddling with a tune he’d started in a guitar workshop in 1963, having cribbed the descending line from Pete Seeger’s “Bells of Rhymney.” Jarrard insisted they cut it without any additional Airplane members present. At first he thought the producer “had lost his mind. A folky, finger-style piece on a rock-and-roll record?” He loved the room echo Jarrard captured. “I’m really glad that he made me to it,” Kaukonen later said. “For me, it bridged the gap between rock and roll and folk.”

“White Rabbit” (another Top 10 Billboard hit as a single just as 1967’s “Summer of Love” blossomed) is next. The bolero snare drum rhythm, the snaking lead guitar and Slick’s uncanny, dramatic vocalizing of lyrics she based on Lewis Carroll have all achieved iconic status.

Recorded on November 3 (the entire album only took two weeks to record), the Airplane slowed down the Great Society version and added a funkified Casady bass part, but it was Slick’s commanding vocal, including the just-short-of-unhinged repeated bellowing of “Feed your head!” at the conclusion that captured lightning.

Related: 1967 in 50 classic rock albums

Balin’s “Plastic Fantastic Lover” completes the album. Cut on the second day of sessions, it’s strong enough to have kicked off either LP side; as a closer it practically mandates the listener turn the record over and enjoy another cycle. Balin’s incessant rant was reportedly inspired by the insipidity of American television and his visit to a plastics factory during a band trip to Chicago. The lyrics are vivid and puzzling simultaneously: “Super-sealed lady, chrome-color clothes/You wear ’cause you have no other/But I suppose no one knows/You’re my plastic fantastic lover.” The entire band is in high gear from the start, reaching a psychedelic peak before Balin even enters. What Kaukonen does on this track—the sound of unfettered joy and creative freedom—sets the template for wannabe psych-out guitarists forevermore.

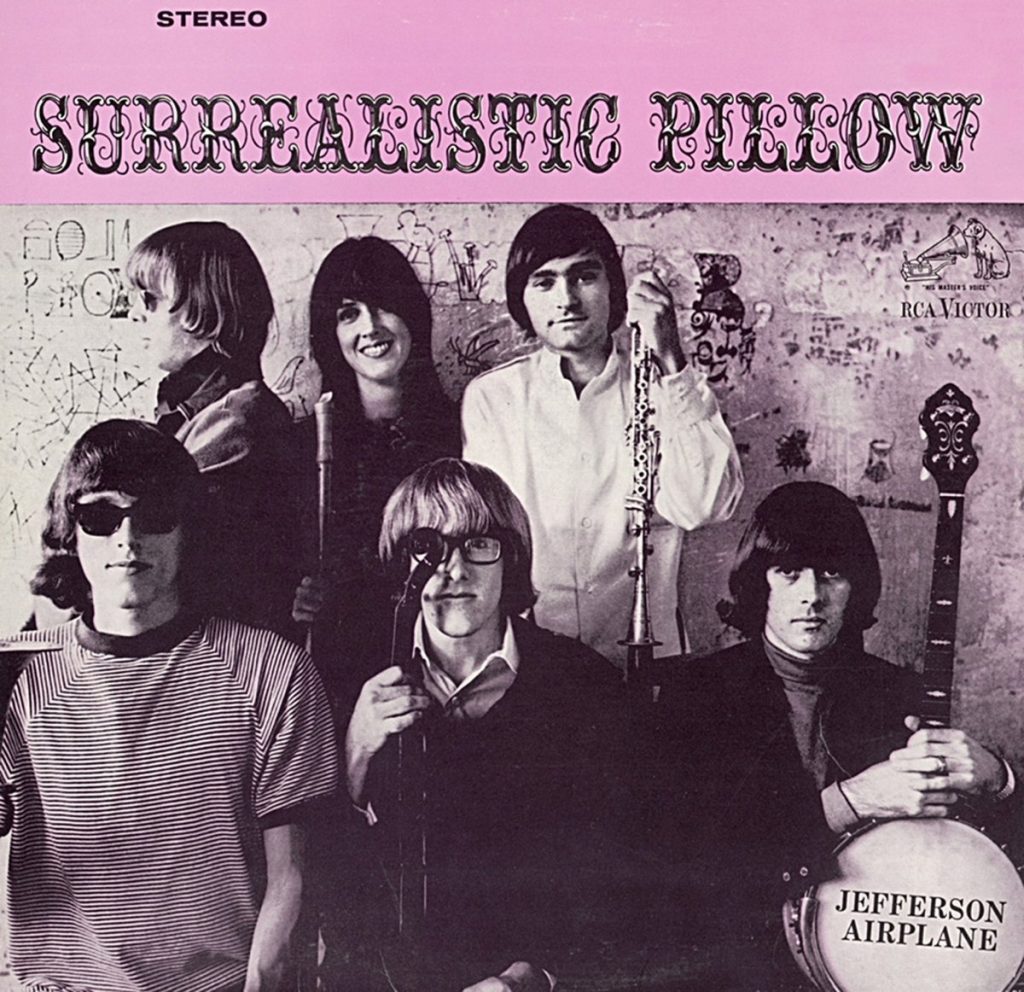

Wrapped in a Herb Greene photo of the band goofing around with various non-rock instruments (taken in front of Greene’s hieroglyphics-covered dining room wall), Surrealistic Pillow, released on Feb. 1, 1967, got to #3 on Billboard’s album chart and sold gazillions for the remainder of the ’60s and beyond. It’s been reissued on CD with several very interesting outtakes (including two Kaukonen vocals that look forward to the Airplane spin-off Hot Tuna). Some prefer the monaural version, which has less reverb in the mixes, but the stereo panning is also candy for your ears. Either way, the original vinyl is still the best way to hear it, whether high or straight.

Grace Slick, pleading an injury, was a no-show for the group’s 1996 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but the rest of the 1966 line-up played “Crown of Creation,” “Embryonic Journey” and “Volunteers,” having turned down the idea of letting Joan Osborne sing Slick’s parts for “White Rabbit” or “Somebody to Love.” Kantner told the assembled press corps, “People didn’t come to the Fillmore to see the bands. We were just some of the louder people on the scene. Grace always said she liked being in the band because it was the least crowded place at the party.”

Dryden died in 2005, Kantner in 2016 and Balin in 2018. Kaukonen and Casady are both still musically active in Hot Tuna and otherwise. Grace Slick retired from music in 1990, but spends her time in her eighties painting and giving the very occasional interview. Although she’s been sober over 20 years, she did admit to one journalist she’s still got some “feed your head” energy lurking inside her: “If Quaaludes came out again, I’d buy a big dark amber glass bottle and keep it in the refrigerator.”

Watch Jefferson Airplane mime “White Rabbit” and “Somebody to Love” on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand

Surrealistic Pillow, and other Jefferson Airplane recordings, are available here.

Related: When Jefferson Airplane auditioned for Phil Spector

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationAnd I always thought that line from “Somebody to Love” was “Your eyes may look like ears.”

So “D.C.B.A-25” is “named after the number assigned to Albert Hoffman’s first LSD batch,” is it? It also happens that D C B A is the chord progression throughout the song. Coincidence? Same thing is true of “Badge” … B-A-D-G-E are the five bass notes that underlie that song, supposedly named for a misreading of a written notation “Bridge?”.

I’m so glad I clicked on this story tonight. I needed to listen to this album more than I knew. Love it. Bought it when it was first released. Marty Balin’s voice insanely beautiful. I thought Today was my favorite song on the album until I was singing along with Comin’ Back to Me and felt like crying because it was so beautiful.

Mark, an overdue thank you for this article, for discussing every song in detail and putting them all up here for us to listen to.

Made my night.