As 1972 came to a close, Eric Clapton had been musically inactive for nearly two years. The guitarist, singer and songwriter had enjoyed a burst of activity in 1969, a period during which he played live and in the studio with Blind Faith, John Lennon (documented on Live Peace in Toronto 1969) and Delaney & Bonnie and Friends (showcased on the duo’s On Tour with Eric Clapton). Near the end of that year, he took part in a one-off celebrity concert in London with Lennon, George Harrison and others to benefit UNICEF.

As 1972 came to a close, Eric Clapton had been musically inactive for nearly two years. The guitarist, singer and songwriter had enjoyed a burst of activity in 1969, a period during which he played live and in the studio with Blind Faith, John Lennon (documented on Live Peace in Toronto 1969) and Delaney & Bonnie and Friends (showcased on the duo’s On Tour with Eric Clapton). Near the end of that year, he took part in a one-off celebrity concert in London with Lennon, George Harrison and others to benefit UNICEF.

In 1970 Clapton played on sessions including Harrison’s All Things Must Pass triple-album. He continued his creative and productive streak with the landmark Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, crediting the release to Derek and the Dominos. That same year, the group, not including guest guitarist Duane Allman, toured and recorded a live album, In Concert; that double LP would eventually be released in 1973.

Clapton did surface briefly in the summer of 1971 in New York City to appear as a backing musician for George Harrison’s all-star benefit Concert for Bangladesh. But other than that admittedly high-profile project, Clapton was absent from the music scene for the better part of 1971 and 1972.

The primary reason for Clapton’s disappearance was his descent into the throes of heroin addiction. His condition was partly the result of (or exacerbated by) his unrequited love for Pattie Boyd Harrison, wife of his friend George.

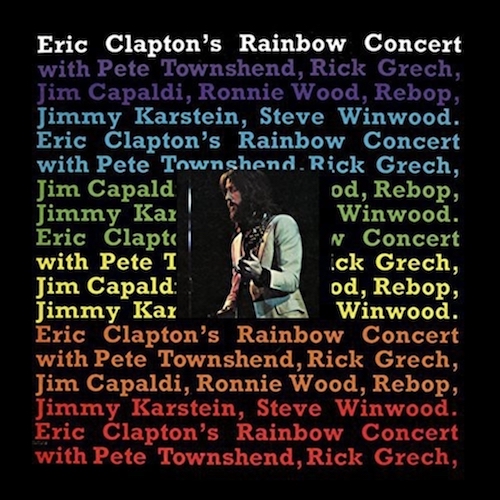

Another friend, Who guitarist Pete Townshend, knew of Clapton’s plight and urged him to return to active musical duty. To that end, Townshend organized a pair of concerts—a matinee and an evening performance—to be held January 13, 1973, at London’s Rainbow Theatre.

Townshend assembled an ad-hoc band to back Clapton for the two shows. Ronnie Wood of Faces (and later of the Rolling Stones) provided support on guitar and vocals, as did Townshend, with Clapton playing lead guitar and (mostly) singing lead.

Two recent associates of Clapton also came to his aid for the Rainbow Concert: singer and multi-instrumentalist Steve Winwood and bassist Ric Grech had only recently concluded their time as band mates with Clapton in Blind Faith. And Winwood brought along some of his Traffic band mates, drummer-vocalist Jim Capaldi and Ghanian percussionist Rebop Kwaku Baah (the latter is credited on the original Rainbow Concert LP simply as “Rebop”). Adding even more percussive foundation to the performances was Jimmy Karstein, late of Delaney & Bonnie and Friends as well as J.J. Cale’s 1972 album, Really.

Listen to “Little Wing” from the Rainbow Concert

Faces bassist Ronnie Lane didn’t participate directly in the concert, but he did provide the facilities of his pioneering 16-track Mobile Studio, built by American audio engineer (and eventual producer) Ron Nevison, to capture the performances on tape. Glyn Johns’ previous production work with the Beatles (Let it Be sessions), the Who (Who’s Next) and Faces (A Nod is As Good as a Wink…to a Blind Horse) made him the ideal person to produce the Rainbow Concert.

A brief 35-minute audio document of the concerts was released by RSO Records in September 1973, but more than two decades later, a remastered release provided a much fuller representation of the two Rainbow concerts, doubling the album’s length and featuring 14 songs that, drawing from both shows, re-created the experience of hearing a full set of music.

The set list as showcased on the 1995 remastered edition of Eric Clapton’s Rainbow Concert features songs from Derek & the Dominos, Blind Faith, Cream and Clapton’s self-titled 1970 solo album. The set also includes an early Traffic song, “Pearly Queen” with a lead vocal by Winwood. Some of the tracks on the 1995 reissue are longer than their original vinyl-release counterparts; others are shorter. But unlike many one-off all-star concerts that would follow in the decades to come, Eric Clapton’s Rainbow Concert is largely free of the aimless jamming that so often characterizes such events.

After an announcer introduces the assembled musicians as “Eric Clapton and the Palpitations,” Clapton fires off the memorable riff that opens “Layla.” Backed by the guitar firepower of Townshend and Wood, Clapton is able to deliver an impassioned, tight live reading that the one-guitarist Derek and the Dominos couldn’t ever pull off live (it’s worth noting that neither live Dominos album features a performance of “Layla”).

For the song’s elegiac, piano-led second half (credited to drummer Jim Gordon but based on a melody from Rita Coolidge), Winwood takes center stage. Ronnie Wood does a workmanlike job of re-creating Duane Allman’s memorable slide guitar solo, but his instrument is quieter in the mix than Clapton’s guitar.

Clapton had collaborated with George Harrison to write “Badge,” a song that originally appeared on Cream’s swan song, Goodbye. Though Harrison, who played on the studio version under the alias “L’Angelo Misterioso,” isn’t present here, the live version hews quite close to its supremely melodic studio counterpart.

Eric Clapton’s solo career would be characterized largely by mellow, laid-back songs; he’d earn commercial, if not always critical, success with songs like “Wonderful Tonight” and “Tears in Heaven.” But on his solo debut, he served up a midtempo rocker called “Blues Power.” Opening with the provocative line “Betcha didn’t think I knew how to rock ’n’ roll,” the guitarist nicknamed Slowhand proved that, indeed, he did. At the Rainbow Concert he tackles the song with a bit more boogie feel, and an impressive guitar solo, but otherwise follows the studio version, adding an extended vamp at its end.

Co-written with keyboardist Bobby Whitlock, Clapton’s “Roll it Over” first appeared on the Layla album. A deceptively straightforward blues, the song features a snaky lead guitar line and a shifting chord sequence that’s musically a cut above the rote blues purveyed by many acts of the era. Clapton and his ad-hoc backing band settle comfortably into the groove of “Roll it Over.”

Jimi Hendrix died in September 1970, and Clapton reportedly took the death of his fellow guitarist rather hard. A cover of “Little Wing” in tribute to Hendrix was a highlight of Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, and a live reading is featured in the Rainbow Concert. Clapton and the band take the tune at a measured pace, highlighting the pathos and majesty of the composition. The crosstalk of two lead guitars adds a pleasingly “busy” feel to the performance.

The relatively undistinguished “Bottle of Red Wine” is a standard if uptempo I-IV-V blues tune that appeared originally on the 1970 Eric Clapton album and as the B-side to the “Blues Power” single. The band has fun with the tune live onstage, and the arrangement does provide plenty of space for Clapton to solo over the top of the familiar chord changes.

The Rainbow Concert version of Clapton’s “After Midnight” (written by J.J. Cale) is remarkably different from its studio counterpart. The recording on Eric Clapton features a kinetic rhythm section full of shakers and other percussion that move the song along. The live version is technically taken at the same tempo, but the simpler arrangement loses the quality that helped make the song special. It’s worth noting that on his 1979 live album Just One Night, Clapton played the song with a lively arrangement much more faithful to his original studio version.

The impassioned slow burn of “Bell Bottom Blues” is among the strongest tracks on Derek and the Dominos’ sole studio album; it’s a major highlight of Rainbow Concert as well, with the upper-register harmony vocals that characterize its chorus.

After a bit of seemingly ad-libbed commentary from Pete Townshend (a few words about how well rehearsals for the show had gone, and an aside about drummer Jim Capaldi having contracted an STD), he leads the band into “Presence of the Lord,” a meditative Blind Faith number with a lovely Steve Winwood lead vocal.

Listen to “Why Does Love Got to be So Sad” from the Rainbow Concert

Clapton takes the spotlight once again for the soulful “Tell the Truth,” another Clapton co-write that benefits from the involvement of Bobby Whitlock. Interesting chord changes enliven the shuffling, melodic song, and the live band serves up a faithful reading. Though he’s ultimately deep in the mix, well below even Pete Townshend’s rhythm guitar, Ronnie Wood plays some very tasty slide guitar. The live version does go on a bit long, but placed in the middle of the performance, it’s not an unwelcome occurrence.

Clapton introduces “Pearly Queen,” the second track on Eric Clapton’s Rainbow Concert to feature a Steve Winwood lead vocal. The performance is a bit loose-limbed, but holds fairly close to the original version as featured on Traffic’s second, self-titled album from 1968.

The first of two blues classic in the Rainbow Concert set list is Big Bill Broonzy’s “Key to the Highway.” Clapton had first recorded it in the form of an impromptu jam during the sessions for Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs. Even in edited form, that studio version ran in excess of nine minutes. For the Rainbow Concert, or at least in the version featured on the 1995 remastered release, Clapton and band wrap up the tune in less than six minutes. Again a bit low in the mix, Ronnie Wood turns in a superb slide guitar solo, one that effectively upstages Clapton’s more conventional solo that follows it.

One of Clapton’s first and most effective forays outside the blues idiom was his 1970 single “Let it Rain.” With a signature riff that spotlights the musical dialogue between lead guitar and bass, the song is one of the brightest spots in Clapton’s solo catalog. The Rainbow Concert band seems quite comfortable with the song’s simple, straightforward structure, and makes the most of it. Winwood, in particular, digs into the song and plays some deeply textured organ runs throughout. The song-proper is over in less than three minutes; from that point forward “Let it Rain” transforms into a free-for-all jam in the style of Derek and the Dominos (or the “Apple Jam” disc included in George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass). A full two minutes is taken over by a drum “solo” (featuring the band’s three percussionists); following that, the jam section returns for a final minute.

Clapton takes an opportunity to thank Townshend for putting the event together (“because I wouldn’t have done it if it hadn’t have been for him,” he admits), and then the assembled musicians close the set with “Crossroads,” the Robert Johnson blues classic that had been a centerpiece of Clapton’s live sets with Cream. With the ad-hoc band, Clapton takes the tune at a much less frenetic pace, and there’s a sense that the band, or at least Clapton, is getting tired by this point. But all involved do their best to deliver a spirited reading of the song, which stumbles to an end in under four minutes.

It’s widely believed that Pete Townshend’s successful efforts to bring Eric Clapton out of his self-imposed musical exile would mark a turning point of sorts. Soon after the pair of shows at the London venue, the guitarist put his heroin addiction behind him, and by April of the following year he was back in Miami, Florida’s Criteria Studios, where he had cut Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, recording his acclaimed 1974 album 461 Ocean Boulevard.

Clapton, born March 30, 1945, continues to tour. When he does, tickets are available here and here.

Clapton’s extensive recording catalog is available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

5 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationSo glad to see Rita Coolidge FINALLY getting credit!

“Roll It Over” wasn’t on the Layla LP. The studio version was the b-side to a single, and then a live performance appeared on the In Concert album.

To my recollection, “Roll It Over” is included on the extended edition og the Layla album.

Should be re issued in its entirety.

Had the album. Not a great one in the least. Sloppy a lot.