When the multi-talented singer-songwriter-hellraiser Gram Parsons died on September 19, 1973, at the age of 26, Emmylou Harris had only known him a couple pf years, during which he turned her world around. At the insistence of Chris Hillman, his former bandmate in the Byrds and Flying Burrito Brothers, Parsons had checked out Harris, a struggling singer and divorced single mom going nowhere in the club scene around Washington, D.C. He was smitten, recognizing someone who could inhabit a song lyric as fully as his favorite country singers.

When the multi-talented singer-songwriter-hellraiser Gram Parsons died on September 19, 1973, at the age of 26, Emmylou Harris had only known him a couple pf years, during which he turned her world around. At the insistence of Chris Hillman, his former bandmate in the Byrds and Flying Burrito Brothers, Parsons had checked out Harris, a struggling singer and divorced single mom going nowhere in the club scene around Washington, D.C. He was smitten, recognizing someone who could inhabit a song lyric as fully as his favorite country singers.

As part of a tour with Parsons’ band Fallen Angels in February-March 1973 in support of Parsons’ debut solo album GP, Harris found a role as harmony singer and muse for the married Parsons, who played up their George Jones/Tammy Wynette energy even in the presence of his displeased wife Gretchen. The major Parsons-Harris collaboration Grievous Angel was released by Reprise Records four months after Parsons’ drug-and-alcohol-fueled demise, with Harris’ co-headlining credit moved to the back cover—with no photo—at Gretchen’s request.

Reprise stuck with Harris, releasing her Pieces of the Sky and Elite Hotel albums in 1975 to universal acclaim, chart success and more than respectable sales among both country and rock fans. Harris had no barriers in her choice of repertoire, combining country classics by the Louvin Brothers, Merle Haggard, Don Gibson, Hank Williams, Dolly Parton, Buck Owens, etc., with contemporary material by up-and-coming Nashville rebels like Rodney Crowell, Gram Parsons tunes and some reconfigured Beatles songs.

“I got a lot of inspiration and nourishment from traditional music,” she told writer Parke Puterbaugh, “but I never intended to do only that. Though it was a really important part of what was stoking my engine, I was going into other areas and coloring outside the lines.” Harris could be a joyful singer, but also resonated with dark, deeply sad lyrics that faced the complexity of life full-on. She was that rare singer who could elevate her own empathy into art.

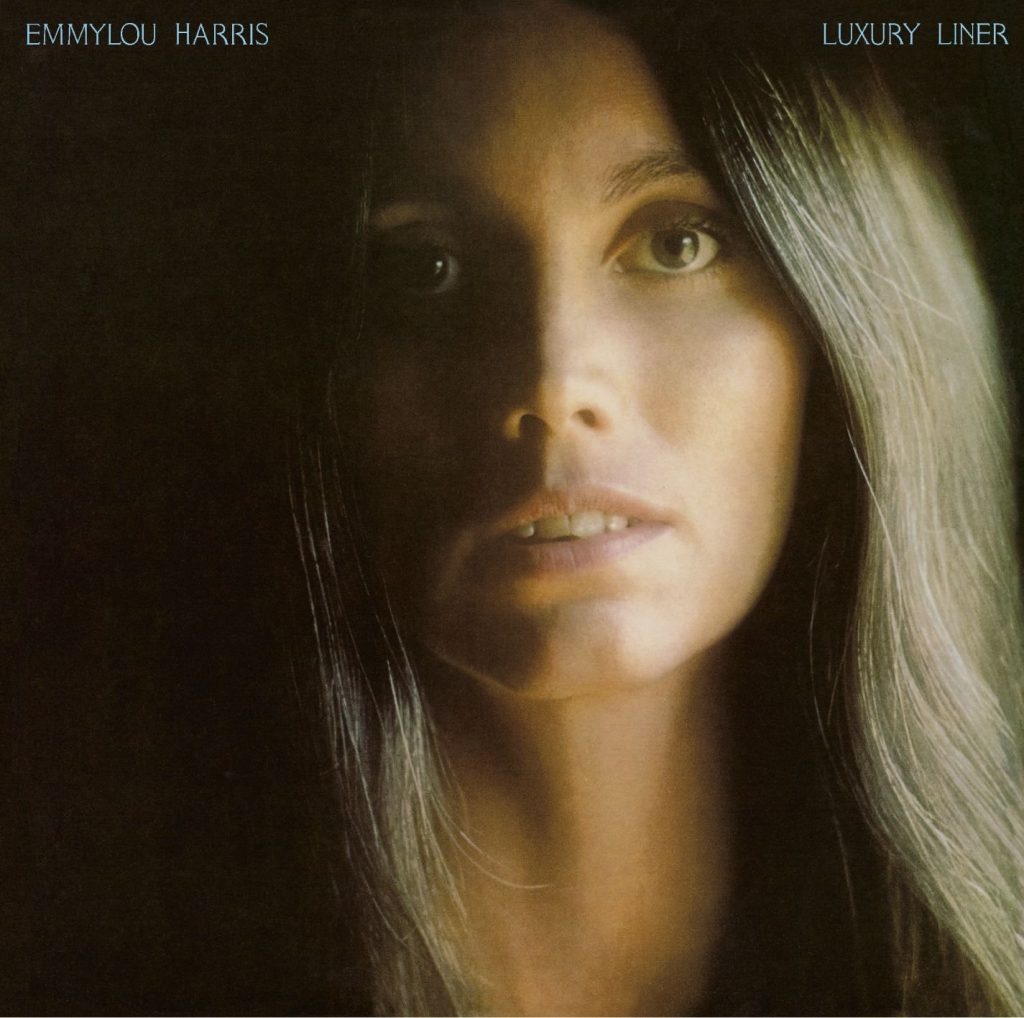

Her third album, Luxury Liner (released on Warner Bros.’ main label instead of the associated Reprise), became her second successive #1 Billboard country album, and didn’t mess too much with a winning formula. Under the steady guidance of producer-engineer Brian Ahern (whom she married a few weeks after the Luxury Liner album release in Dec. 1976), Harris meshes wonderfully with some of the best musicians on the traditional Nashville and “alt-country” scenes, including Elvis Presley’s crack guitarist James Burton, Ricky Skaggs on fiddle and mandolin, Emory Gordy Jr. on bass, Hank DeVito playing steel guitar, keyboardist Glen D. Hardin, and the incredibly versatile country-rock guitar-slinger Albert Lee. Several of the players, including Crowell, were also members of Harris’ tour unit the Hot Band.

Ahern says he used “an aggressive slap echo” on his guitar pickup to drive the opening track “Luxury Liner,” a Gram Parsons song originally done by Parsons’ short-lived International Submarine Band in 1968. With a typically downbeat Parsons lyric (“I’ve been a long lost soul/For a long, long time”), the track takes off like a rocket, with a Sun Records rockabilly feel, the howl of steel guitar and Albert Lee’s series of astonishing solos beginning at one minute in. John Ware’s drumming is key to the propulsion of the cut, and Harris pushes her forceful voice out without compromising her pitch-perfect clarity.

Demonstrating her versatility from the get-go, “Pancho and Lefty” follows. Townes Van Zandt was under the radar of most folk and country fans (and remained that way for much of his extraordinary, tragic career), but Harris had seen him perform in Greenwich Village in the late ’60s, when she was also trying to break into that scene. Harris responded to the harsh poetry in the song she called “the beating heart from which all things emanate” on Luxury Liner: “There was a real dark side to his music that I, of course, absolutely loved.” A detailed yet mysterious story-song, “Pancho and Lefty” has been recorded many times, with the 1983 Willie Nelson/Merle Haggard version being the most recognized. But having a woman as intuitive as Harris sing it brings a different kind of emotion to lines like “He wore his gun outside his pants/For all the honest world to feel.” Her voice, recorded with a light echo effect, breaks just a bit on the resigned “That’s the way it goes.” Ahern and Rick Cunha play acoustic guitars, John Ware is the very effective drummer, Mickey Raphael gets his harmonica to approximate an accordion, Crowell adds a perfect harmony vocal and Hardin’s piano break is instantly recognizable as his work.

Kitty Wells recorded a hit version of Jimmy Work’s ultra-sad “Making Believe” in 1955. Harris connects to the melancholy tale of a jilted lover whose “plans for the future will never come true,” as she/he is stuck in a cycle of fantasy where “I’ll always dream, but I’ll never own you/Making believe, it’s all I can do.” When Harris sings mid-tempo material, her natural vibrato is highlighted, and she seems even more able to connect emotionally to the words. Herb Pedersen, the often-used session backing singer who was once in bluegrass greats the Dillards, excels here, as does Ricky Skaggs on fiddle. Issued as a single, “Making Believe” became a top 10 hit on the country charts.

Rodney Crowell didn’t get around to recording “You’re Supposed to Be Feeling Good” himself until 2023’s Chicago Sessions album. Harris’ debut of his tune is fairly relaxed until the lyrics and chorus melody indicate the turmoil of a complicated love: “You’re supposed to be in your prime now/Not supposed to be wasting your time/Feeling like you’re down and out over someone like me.” The electric guitars are by Burton and Ahern, and DeVito’s steel and Raphael’s harmonica are given good room for punctuation.

Written by Susanna Clark, “I’ll Be Your San Antone Rose” was recorded for RCA by the little-known Texas singer Dottsy [Brodt] in 1975. Clark and her husband Guy were Lone Star songwriting royalty (Townes Van Zandt was best man at their wedding). Harris and company give it a lovely two-step rhythm that greatly improves on the Dottsy original, with all the instrumentalists gifted time to show off, especially Skaggs and DeVito. Crowell and Harris’ South Carolina friend Fayssoux Starling help her sing the choruses.

As a single, “(You Never Can Tell) C’est La Vie” was a slightly bigger hit than “Making Believe.” A jaunty and humorous tale with Cajun accents, it was written by Chuck Berry while he was in prison for violating the Mann Act. He included it on the LP St. Louis to Liverpool; on 45 rpm in 1964 it was his final chart hit of the decade. (It gained a whole new life when Quentin Tarantino featured it in Pulp Fiction 30 years later.) Having a rollicking good time, Harris’ singing partners are Dianne Brooks and Albert Lee, who also supplies part of the stack of guitars that Ahern orchestrates.

“When I Stop Dreaming” begins with the vocal trio of Harris, Starling and guest Dolly Parton, and contains the seeds of the eventual Harris/Parton/Ronstadt group the Trio, which debuted with a multi-platinum album in 1987. Written by Ira and Charlie Louvin, it was included on their seminal album Satan Is Real in 1955, and represented their first steps away from straight gospel. It’s a yearning secular song that Charlie once said illustrated his conviction that “Everybody knows what it’s like to dream. I believe the world is made by the dreamers.”

Harris reaches all the way back to 1938 for the Carter Family’s bouncy “Hello Stranger,” singing in tandem with Nicolette Larson in the style of Maybelle and Sarah Carter. The original bare-bones Carter arrangement is updated with apt fiddle-sawing from Skaggs and Lee’s delicate mandolin, not to mention the understated rhythm section of bassist Emory Gordy and drummer Ware. (A section with Raphael’s bass harmonica might remind some of Brian Wilson’s use of that unusual instrument as spice on Pet Sounds.) Halfway through, as Starling joins in, it all becomes country vocal heaven before yielding to a long instrumental coda.

Harris and Parsons absolutely loved Louvin harmonies, and included a raucous version of the Louvins’ “Cash on the Barrelhead” on Grievous Angel. “When I Stop Dreaming” might be Harris’ best Luxury Liner vocal, as she sings the verses with a virtual catch in her voice, but considering her take on Gram Parsons-Chris Ethridge’s “She” it might be a tie. Parsons wrung every ounce of pathos out of the lyric when he recorded it for GP, and Harris, closely following his arrangement, brings it home with perhaps even more sadness.

The album concludes with a Crowell-Harris co-write, “Tulsa Queen,” with Gordy’s thumping bass, three different acoustic guitar parts by Harris, Crowell and Ahern, James Burton on electric, and Pedersen and Starling backing Harris’ ethereal vocal. The long, gorgeous fade-out belongs to Raphael and DeVito.

Parsons gave his all to play what he called “Cosmic American Music,” and his spirit of exploration was surely taken up by Harris as she built her own musical personality, always acknowledging the debt she owed him. Ahern and Harris divorced in 1984, but he continued to produce her recordings off and on for decades more. The Enactron Truck, Ahern’s lead-lined 42-foot-long semi-truck mobile recording studio, was used for platinum albums by Johnny Cash, Dolly Parton, Black Sabbath, Bette Midler and many others, after it did superb work for Luxury Liner.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Trio, Harris’ first collaboration with Linda Ronstadt and Dolly Parton

Harris has won 13 Grammys out of her well-deserved 47 nominations, became a member of the Grand Old Opry in 1992, and participated in any number of important folk, country and bluegrass events and albums, including the O Brother, Where Art Thou? movie soundtrack, which revitalized country music in 2000. She was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2008 and received the Polar Music Prize in 2015, among other accolades. She’s considered such a sage, there are websites collating her pithiest quotes, including, “I’m just too busy living every day to spend a lot of time thinking ‘am I old?’ I’m this age. I am in this moment and in this life.”

Her albums are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Listen to “Me and Willie” and “Night Flyer,” a bonus tracks on the 2004 reissue of Luxury Liner

6 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThanks for this insightful overview of a period in time I’ll be never forget. Emmylou remains the Queen of real country music

LL is a great LP. But the next one, “Quarter Moon in a Ten Cent Town” (awesome lyric from my fave Emmylou song) is (for me) her absolute best. Is there a more heartbreaking/getting over it song? I think not.

Didn’t susanna clark write the song? i know she created the cover for the album… i agree, it’s a lovely album!

When I got Luxury Liner, I was 15. In the 70s. I sang all the songs, and Fell in Love with Poncho and Lefty. I later met Jeff Beck in California, and had him sit and listen to me singing it. It meant so much to me to share it with him. She is so real a person. A true Country girl. I should know, I grew up country, in the deep south, and in Nashville, Tennessee. Thanks for writing about this. I knew this was a great record. Joan Bryant – in Hollywood. Watching Willie Nelson on his 90th.

My first Emmylou Harris album purchase when I was 14 in 1977…and have been a believer and a fan ever since.

I wish I could interview Ms. Harris about “You’re Supposed To b Be Feeling Good” which is my favorite song of hers. Such a masterpiece. She reminds me of my mentor.