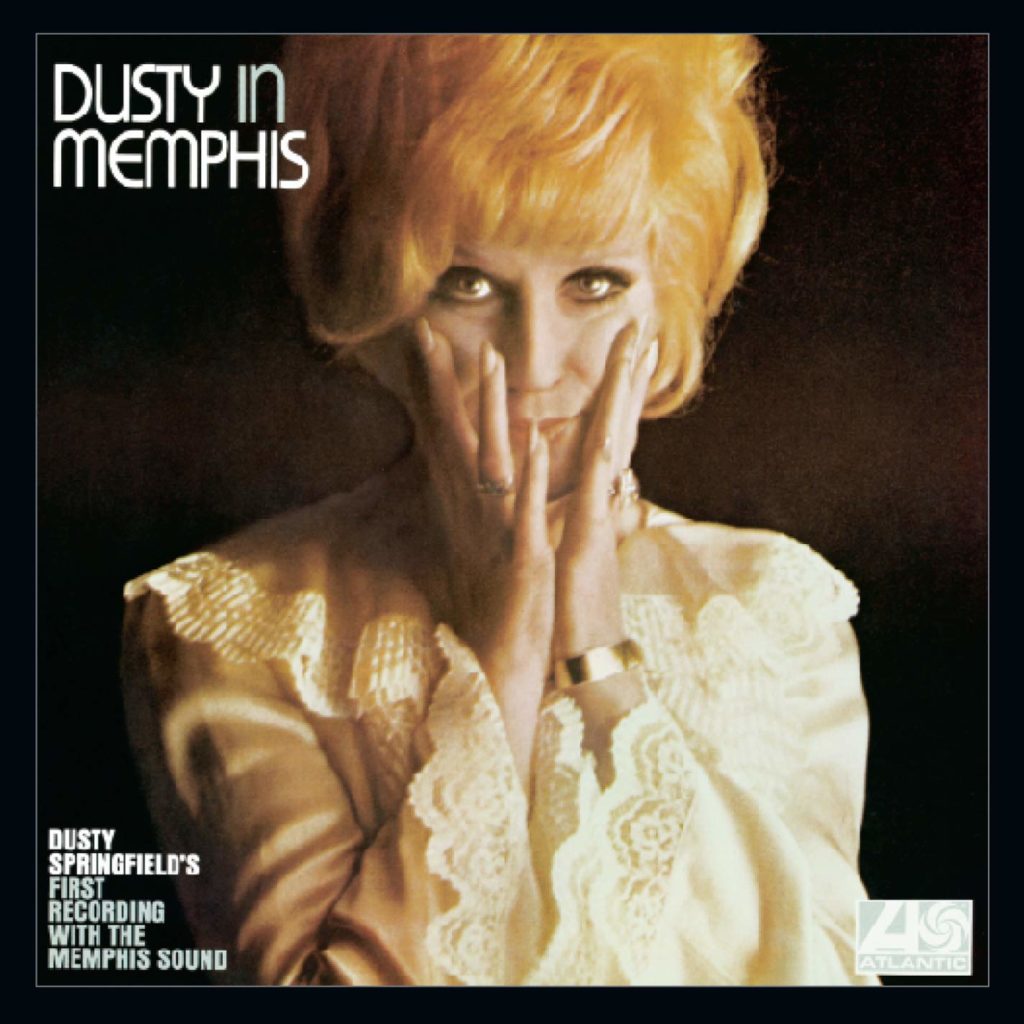

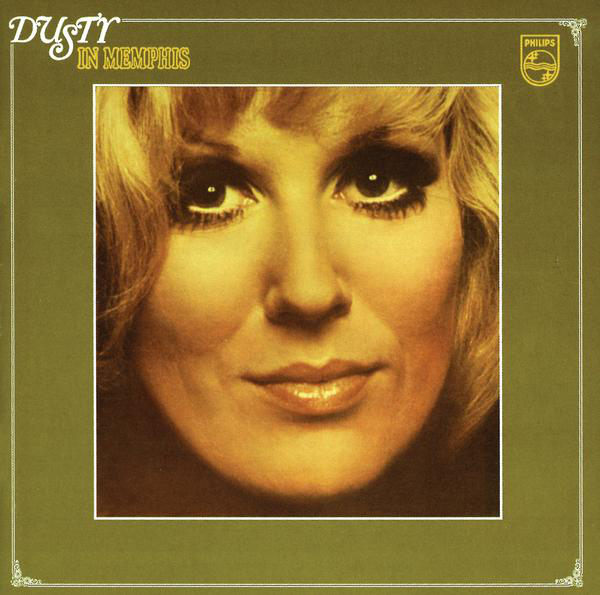

The Dusty Springfield Pop-Soul Pinnacle: ‘Dusty in Memphis’

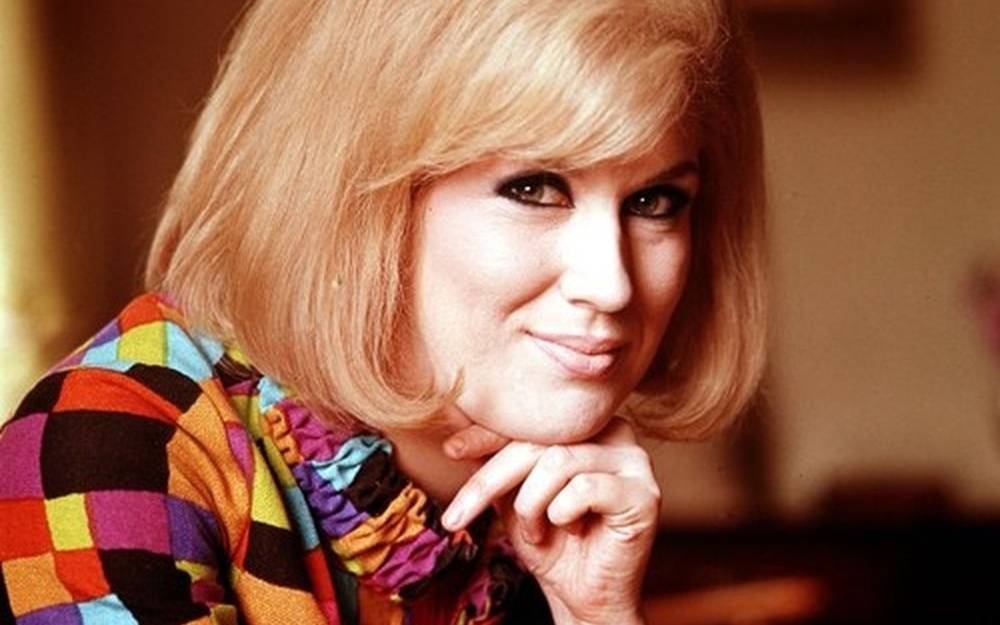

by Sam Sutherland When Atlantic Records began courting Dusty Springfield in 1968, the attraction was mutual. She was the decade’s pre-eminent British pop female vocalist, a Mod icon and TV star crowned the “Queen of White Soul” for a lush style steeped in American pop and R&B influences. For her, Atlantic was hallowed ground, home to a pantheon of R&B titans from Ray Charles, Ruth Brown and the Drifters to Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Booker T. and the MG’s, and the reigning “Queen of Soul,” Aretha Franklin.

When Atlantic Records began courting Dusty Springfield in 1968, the attraction was mutual. She was the decade’s pre-eminent British pop female vocalist, a Mod icon and TV star crowned the “Queen of White Soul” for a lush style steeped in American pop and R&B influences. For her, Atlantic was hallowed ground, home to a pantheon of R&B titans from Ray Charles, Ruth Brown and the Drifters to Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Booker T. and the MG’s, and the reigning “Queen of Soul,” Aretha Franklin.

For both label and artist, the timing was propitious. Deals with the Bee Gees and Cream signaled Atlantic’s ambitions to add British talent to its roster, while Springfield sought creative renewal as she battled the headwinds of the late ’60s rock, pop and soul innovation after rising to prominence.

At 29, she was a relative elder whose first American hit predated the British Invasion. “Silver Threads and Golden Needles,” transformed a 1956 Wanda Jackson recording into a banjo-flecked folk-pop lament for the Springfields, the trio that prompted London-born Mary Isobel Catherine Bernadette O’Brien and older brother Dionysus to become Dusty and Tom Springfield. That 1962 release was the first single by a British group to crack Billboard’s top 20, achieved two months before the Tornados scored a global instrumental hit with “Telstar” and 15 months before the Beatles’ U.S. debut.

As the Beatles erupted, Dusty Springfield was close behind with her debut solo single, “I Only Want to Be with You,” a major hit in the U.K., Australia and Canada that reached #12 in the U.S. in early 1964. Her debut left her earlier style behind, emulating the girl group hits she heard on a trip to Nashville, starting with the Exciters’ “Tell Him,” propelled by an unbridled lead vocal that galvanized the young British singer. Springfield’s maiden hit borrowed liberally from Phil Spector’s toolbox with strings, horns, choir and double-tracked vocals; subsequent singles and album tracks were sourced from Brill Building tunesmiths and Motown’s staff songwriters.

To produce her label debut, Dusty in Memphis, Atlantic senior exec and producer Jerry Wexler teamed with arranger Arif Mardin and engineer Tom Dowd, booking sessions at that city’s American Recording Studios. The rhythm section featured first-call Memphis players Reggie Young (guitar), Tommy Cogbill (bass), Gene Chrisman (drums) and keyboard players Bobby Emmons and Bobby Wood, with the goal of building spare arrangements that would keep Springfield’s honeyed voice in the foreground.

Wexler sought to emphasize the subtler attack Springfield had displayed on “The Look of Love,” the Burt Bacharach-Hal David ballad for 1967’s Casino Royale, in which her hushed vocal ached with a palpable erotic longing that left the girlish intonation of her early hits far behind.

Memphis R&B shaped the album’s arrangements, but the project didn’t abandon the songwriters that Springfield favored as she and Wexler battled over the material. Nine of the album’s 11 tracks came from Brill Building or Hollywood songsmiths, starting with the opener, “Just a Little Lovin’,” by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, featuring the bedroom languor Wexler sought. The song generates a sexual frisson in an early morning wake-up call that promises to “beat… a cup of coffee for starting up the day,” delivered by Springfield with a sleepy, feline sensuality.

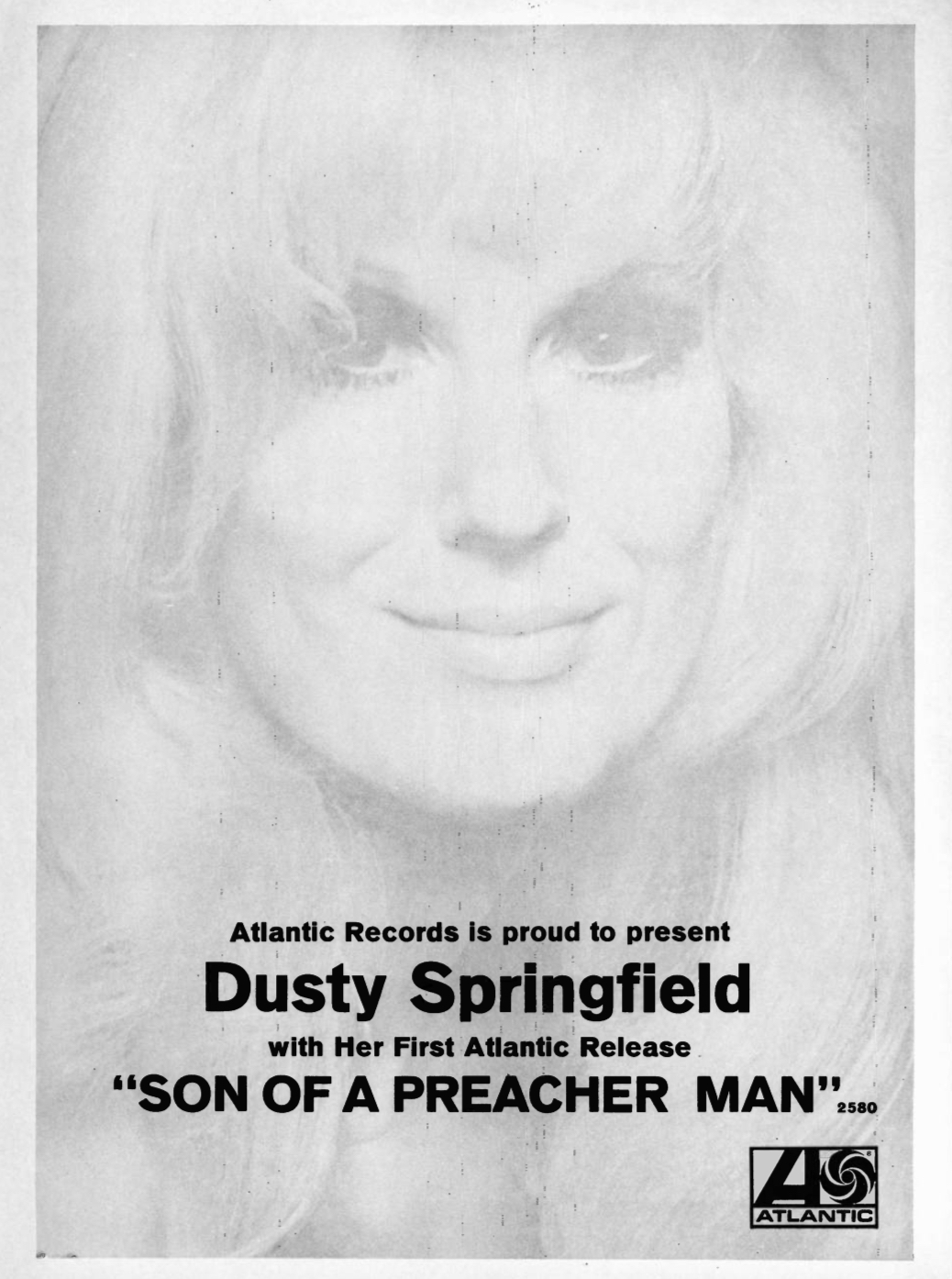

Erotic heat provides a common denominator for the two songs that did come from Southern writers, starting with “Son of a Preacher Man.” Aretha had passed on the John Hurley and Ronnie Wilkins composition, leaving Springfield to celebrate its worldly pleasures with a simmering performance that yielded a top 10 hit in the U.S., the U.K., and eight other countries.

An intimate, adult reverie finds the singer remembering the titular beau’s backyard seductions in a coy, then fevered whisper before a delicious moment of erotic discovery (“Lord knows, to my surprise!”) leads into a full-voiced, ecstatic chorus. The arrangement is classic Memphis R&B, its clipped pace buoyed by Cogbill’s nimble bassline and Young’s sinewy fills and punctuated with crisp horns and the call-and-response of the backing vocals.

This ad for the single ran on Nov. 16, 1968, two months before the LP’s release.

“Breakfast in Bed,” by Alabama session veterans Eddie Hinton and Donnie Fritts, puts a winking spin on her earlier hit, “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” inverting its stoic heartbreak into laissez faire passion. A secret tryst finds the singer consoling her lover over another relationship with an invitation to “dry the tears on my dress,” before offering “Breakfast in bed/and a kiss or three/you don’t have to say you love me.” If her lover feels pain, Springfield sounds frisky, thanks to the playful melody and sinuous arrangement, which would invite numerous R&B and reggae covers.

Among other songwriters featured, Gerry Goffin and Carole King supply four songs that tap rapture (“So Much Love”), resignation (“No Easy Way Out”), romantic surrender (“I Can’t Make It Alone”) and urgent passion on the set’s most exuberant, uptempo romp, “Don’t Forget About Me.” A towering vocal display is infused with some of Cogbill’s and Young’s most inspired playing, textbook examples of their skill at embroidering the arrangement while leaving an open lane for the singer’s voice.

The album’s other single hit was a stylistic outlier that Springfield resisted, “The Windmills of Your Mind,” composed by Michel Legrand with lyrics by Alan and Marilyn Bergman for The Thomas Crown Affair. The singer couldn’t relate to the song’s stream-of-consciousness lyrics, but her performance and Mardin’s most expansive orchestral arrangement reached the top 30.

Completing the album was another atmospheric Bacharach-David reverie, “The Land of Make Believe,” and two Randy Newman songs. “Just One Smile,” one of Newman’s most covered early songs, receives a superb reading that holds its own against Gene Pitney’s original single and numerous other covers (including Blood, Sweat and Tears’ early ’68 version), but Newman’s standout moment on Dusty in Memphis arrives during her version of “I Don’t Want to Hear it Anymore,” first cut by Jerry Butler in 1964.

Newman creates a gritty, urban tableau of heartbreak through conversations overheard by the singer through thin tenement walls. As neighbors gossip about “the boy in room one four nine,” she learns of his imminent desertion, her desolation rising through the singer’s wrenching performance. Originally planned as the album’s third single, “I Don’t Want to Hear it Anymore” was blocked by an Oscar nomination for “The Windmills of Your Mind,” with Atlantic pressing two separate runs of promo singles. Alternate “Windmill” A-sides were ready when the song won the award, with the label shipping those copies the next day.

For Springfield, the project was challenging if not unnerving. Having effectively self-produced her Philips tracks, the album marked her first with outside producers, as well as the first sessions in which she was working with the basic rhythm section prior to orchestral overdubs or individual fixes. She was also reportedly intimidated by working in a studio that was hallowed ground for soul and pop heroes. While the basics were completed at American Recording, Dusty would track her vocals in New York.

When Dusty in Memphis arrived on Jan. 18, 1969, it was a critical triumph but a commercial defeat, stalling at #99 on the album chart, yet its stature as a timeless pop work has only deepened, despite the turbulent arc of her subsequent career and her death at the age of 59 from breast cancer. Dusty Springfield’s influence on other singers has likewise outlived the disappointments of her post-Atlantic work, most strikingly among this century’s British female pop singers. Adele, Duffy, Amy Winehouse and Joss Stone are only the most obvious heiresses to Springfield’s white soul legacy, captured in its purest form on Dusty in Memphis.

Bonus Video: Watch Dusty Springfield and Tom Jones sing “I’m Gonna Make You Love Me”

Related: Springfield’s “The Look of Love” is one of our “Lost British Invasion Hits”

Her recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThanks for your review. As many may know, Aretha Franklin went on to record “Son of a Preacher Man”, for her 1970 “This Girl’s In Love With You” album. Of course, her version is gritty and fierce, complete with many shouts of “hallelujah!” after a simmering section that builds up to a big climax. It’s said that Dusty loved Aretha’s version so much that she started signing the song in concerts, using a style that showed Aretha’s influence. Thanks again!

Play it again Sam! Ditto on the great report!

Thanks for a DUSTY-Ing review….

Bought “Dusty In Memphis” CD at a church yard sale; remastered version yet, and in pristine condition.

Perhaps the previous owner had passed on, and it was donated with a box of other belongings, but suffice to say, it is the best dollar I ever spent.

Definitely in my personal collection’s top twenty list.