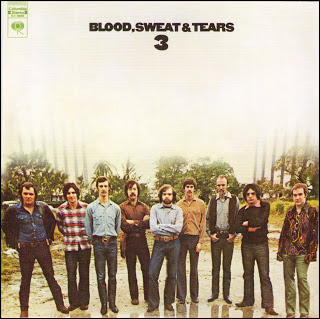

In the first part of our extensive 2019 interview with David Clayton-Thomas, the renowned vocalist took us from his Toronto roots to the streets of Greenwich Village and superstardom as the frontman of Blood, Sweat & Tears.

In the first part of our extensive 2019 interview with David Clayton-Thomas, the renowned vocalist took us from his Toronto roots to the streets of Greenwich Village and superstardom as the frontman of Blood, Sweat & Tears.

We begin the second and final part of our conversation talking about the biggest gig the band ever had—the biggest gig just about anyone could ever have—at the August 1969 Woodstock festival. The Canadian singer also talks about why he left—and then returned to—BS&T, his subsequent solo career and his strong opinion on the later years of the band he took to the top of the charts and finally left 15 years ago.

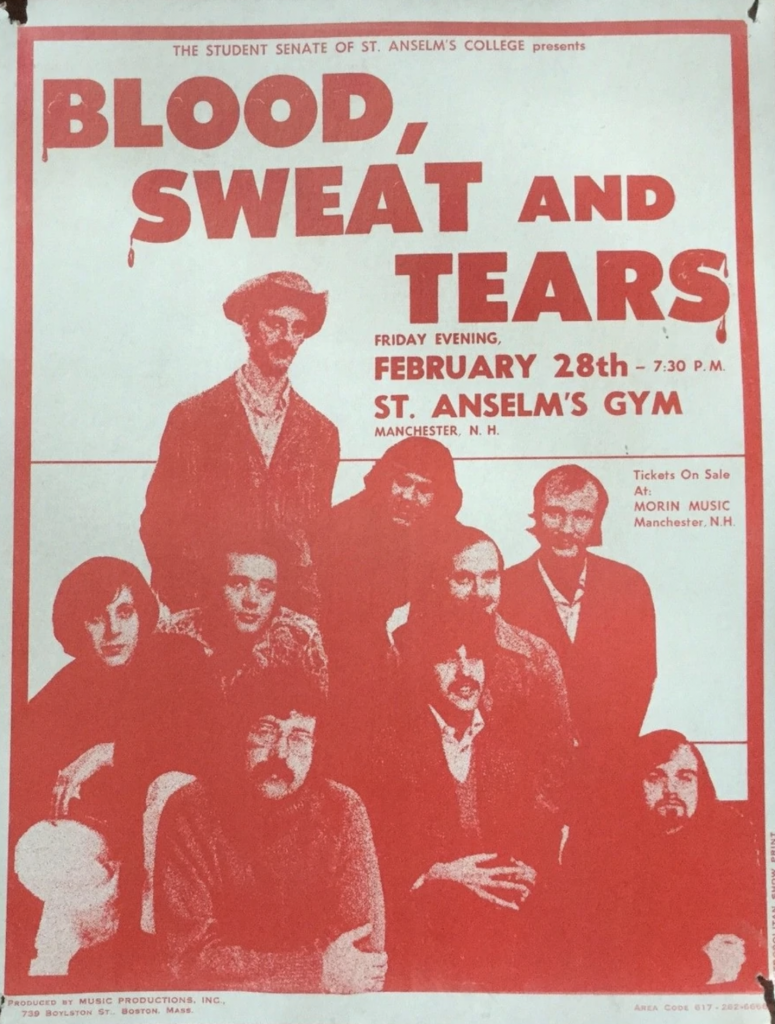

Best Classic Bands: Let’s talk about Woodstock. BS&T had been touring constantly and then you got a call to come play this festival in upstate New York. Did you have any sense in advance that it was going to be different?

David Clayton-Thomas: No, we didn’t much keep track of the itinerary or where we were going. If you’ve ever been on the road, you wake up in the morning and you look at the telephone book beside your bed to find out where you slept last night and ask the road manager where you’re going next. And of course on the road the most valuable thing is trying to get enough sleep. You go to bed at midnight after a show. You have a 3 o’clock wake-up call to get to the airport, so you get your sleep an hour or two at a time. So no, we didn’t really know where we were going; we just knew there was a gig in New York. We didn’t really understand what was happening until we landed at LaGuardia Airport. And the road manager said, “I don’t think the show tonight’s going to happen. All the traffic is jammed. Nothing is moving. There are 600,000 at this concert.” We stayed at LaGuardia all afternoon. A lot of the guys were worried because we were a hometown band and we had friends and family and wives and we’re stuck in this mess out on the highway. We couldn’t communicate so we were very worried about what we were going to do next, and by mid-afternoon the governor of New York State had declared the area a national disaster area and mobilized the National Guard. There were 600,000 people and maybe six cops and a couple of state troopers for the little local surrounding towns. How do you control 600,000 people with six cops? And if the artists didn’t show up, there might be a riot. So, we got about a third of the way there before the traffic completely stopped and we went to a little motel and they brought in a National Guard helicopter and flew us into the site.

What was your first impression when you looked down and saw that mass of people?

It was awesome. I had never seen anything like it. That was the year of gigantic festivals. We had played Atlanta [International Pop Festival]. We played the Varsity festival [Toronto Pop Festival at Varsity Stadium] in Toronto, which was like 40,000-50,000 people. They [the large festivals] died very, very quickly. They were unmanageable; they were unprofitable. They just didn’t work. Woodstock was a financial catastrophe for the promoters.

Watch Blood, Sweat and Tears perform “I Love You More Than You’ll Ever Know” at Woodstock

How did your set go over with the audience?

Everybody there knew us. I would say 70 percent of the people in that audience were from New York, and we were a New York City band. That was our base. They’d seen us play in clubs and colleges around the New York area. We didn’t get too much of a Woodstock experience. We were literally dropped backstage maybe an hour before the show. I ran into Crosby, Stills and those guys backstage; I knew Stephen Stills from Toronto. And the Band was there; they were my old buddies. I was in that band at one point, [when they were] Ronnie Hawkins’ band. I was the second singer in that band. We had a chance to chat a little bit backstage and then it was onstage. We did our show, our one hour, got off and the people were going crazy and the promoter actually came out and said, “Go back on and give them an encore.” We came offstage and literally went right back onto the helicopter. We were out of there.

So when did you realize this was a very special event?

It dawned on us over a period of time. When you stand onstage and you’re playing to half a million people, it’s pretty hard to ignore the reality of that.

Why wasn’t BS&T in the Woodstock movie?

Backstage there was a lot of controversy going on. The managers were in a trailer with the promoters, going, “How does my band get paid?” They [the promoters] said, “They broke down the fences. We don’t have any money.” So some of the managers, in particular Albert Grossman, who managed Dylan, the Band and Janis [Joplin], said, “OK then, no pay, no filming.” The headliners, in their contracts, had a percentage of the film rights. Since there was no money to give them [the bands], they simply just edited us out of the film. I think they actually recorded only one song at Woodstock. But the quickest way to not pay the headliners is just edit them out of the film. I’ve got to live with that, with my daughter going, “Dad, I thought you were at Woodstock. I saw the movie and you weren’t in the movie.” The managers felt that was the only leverage they had to get their bands paid. And it’s not just greed. I mean, it was financial reality. We had airfares to pay, we had musicians to pay, we had road crew to pay and we weren’t going to get any money for this gig. Normally, if we we’re doing a concert and the promoter didn’t come up with the money you just don’t put the show on. It’s his problem. You can’t do that with a half a million people.

You left the band for a few years in the early ’70s, after the fourth album, and then returned. What was that about?

Well, the manager at the time, a gentleman named Larry Goldblatt, was very insistent that we were touring too much. Not only was the band getting overexposed but I was losing my voice. We didn’t have the sophisticated earbuds and monitoring systems we have today. I was out there in stadiums every night belting it out in front of this big loud horn band. The manager lobbied the band several times. He called meetings: “We’ve got to cut down on the touring. We’ve got to get off the road. David is burning out. His voice is literally going.” Eventually, he was fired. He was voted down and voted out, and when he went I realized that it was out of control. Nothing was going to happen. It was a gigantic money-making machine and it only made money if it stayed on the road. So if they weren’t going to give me a break I took it myself.

Listen to BS&T’s 1970 Top 20 single “Hi-De-Ho”

You started making solo albums around that time.

That’s why I moved out to L.A. I did a couple of solo albums. I had stayed in touch with [drummer and band manager] Bobby Colomby—he and I had been friends all the time. And he said, “How is it working for you?” And I said, “Not so good; people want the Blood, Sweat and Tears name. How’s it working for you?” And he said, “Not so good; people want David Clayton-Thomas.” So I said, “Let’s give it another shot.” So I flew into Milwaukee where they had a concert and at the end of the concert, I walked onstage and the place went wild, because that’s what people came to hear. They wanted to hear the voice that was on the record.

Watch Clayton-Thomas sing “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy” with the 1993 incarnation of BS&T

You stayed with them all the way to 2004, with another short break along the way, and they carried on with other singers.

There’s still a Blood, Sweat and Tears out there now, which is basically a tribute band. I don’t even know this band—this isn’t Blood, Sweat and Tears. They should maybe have the Integrity to call it a tribute band because it’s not Blood, Sweat and Tears. And anybody who saw Blood, Sweat and Tears in the glory years knows. There was tremendous improvisation and firepower on that stage. It’s not there anymore.

Was there ever a point while you were still involved when it stopped feeling like Blood, Sweat and Tears to you?

It was a gradually eroding process. It’s not like everybody left one day; you know, one guy would leave and be replaced. And if he’s being replaced by somebody like [jazz musicians] Mike Stern or Jaco Pastorius or Larry Willis, who would complain about that? But I think the final straw for me in 2003-2004, when I gave my notice, was they hadn’t been in a recording studio in 30 years. I’m a songwriter. I had a guitar case full of songs I was dying to record. And as long as I was in that band, they’d never get recorded because they had basically deteriorated into a tribute band. That happens to a lot of acts: you get that one big hit record and then all the promoters want you to do is play that record for the rest of your life. Creative people want to make new music. When I did finally leave in 2004 and moved to Toronto, I recorded three albums in the first two years. I had tons of material that I had to get out of my system, that I’d been writing for the past 20 years and never got the opportunity to record.

Some of your solo albums from the past decade, like Soul Ballads and Combo, are excellent. Are you working on a new one?

The new album is killer but you won’t hear it for several months. The Mobius album [2018] did very well so we went back in the studio and I wrote an album called Say Something. It’s a commentary on everything that’s going on in this wacky world, from climate change to politics to immigration—all the stuff that’s out there. I teamed up with a very good quartet of musicians.

Listen to the track “Downbound Train” from DC-T’s 1972 solo album Tequila Sunrise

Will you be going back out on the road?

I’m not touring so much anymore. I’ll do a half a dozen select concerts a year. A couple of years ago I headlined the Toronto Jazz Festival downtown. Great gig. I did two nights at Massey Hall with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. But to just be on the road to put gas in the bus, I can’t do that anymore.

How would you sum up Blood, Sweat and Tears’ contribution to music?

The press zeroed in on the fact that we were a horn band, that we brought horns into rock ’n’ roll, but that’s not true. Little Richard and Fats Domino and Chuck Berry had horns. Ray Charles was using horns. No, I think what we brought into it was that very unique New York City flavor. The influences were everything from Broadway shows to Duke Ellington to pure jazz in the Village, salsa being played in Spanish Harlem. Only New York has that kind of compressed melting pot. And that’s what we brought in: arrangements. I think that was the important thing, much more so than the fact that we had horns.

Listen to David Clayton-Thomas’ cover of Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come” from his 2010 solo album Soul Ballads

Blood, Sweat and Tears’ recordings are available in the U.S. here and in Canada here.

7 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationUnreal in both the tight musicianship, as well as the fidelity of the live recording. Woodstock may have had its chaos, but they sure got documenting the event right. I always felt that BS&T never really got their due for the amazingly accomplished band they were, that could cover so many different styles and genres at will in a very cinematic way. No offense meant to all the other horn bands, but I have to laugh when others are cited as great horn bands before BS&T. There was no group who was even close to their musicianship. I think whether you like them or really comes down to whether you like David Clayton Thomas, who is an undeniably talented singer. For myself, I liked their hits with him, and it’s hard to dispute the overall greatness of that second BS&T LP, (the first with Thomas). But for my money, I will always have a special place in my heart for the first BS&T album, with Al Kooper as their primary vocalist and songwriter. Kooper may not technically be nearly the singer that Thomas is, but his vulnerability gives the band a different flavor than Thomas’ blue-eyed soul does. And I personally think Kooper’s BS&T is much more of that “new York Sound” that Thomas speaks of, that Thomas’ version.

To continue with Da Mick’s fine comments about Al Kooper . . . check out Kooper’s version of “Hey Jude”.

Yup, I agree with DM 100%. I was bummed when Kooper got the boot. The 1st BS&T album was the one that really grabbed me. The others were too mor for my taste.

Being a “gigging” musician for 60 years, I’ve had to play the hits of other artists for years. That is what the civilians want. But if I never hear “What goes up, must come down” again, it will be too soon. It’s tied with “Color my world” for the “gag me with a spoon” award.

Two great songs but…

I’m a fan of DCT – even read his biography about three years ago – and love the second, third (to a lesser extent), and fourth albums, and also enjoyed bits and pieces of the albums after that, but that first album with Kooper had an edge and subversiveness to it that none of the others had.

Similarly, there was the absence of Creedence from the Woodstock movie, as well….and many people had no clue that they played it, either. Much like BST.

That guy is perhaps my favorite singer of all time. There’s just something about his voice that moves me whenever I hear it. It’s been that way since the sixties and it still grabs me whenever I hear DCT sing. What a sound he has! And no one–I mean NO ONE–sounds like him.