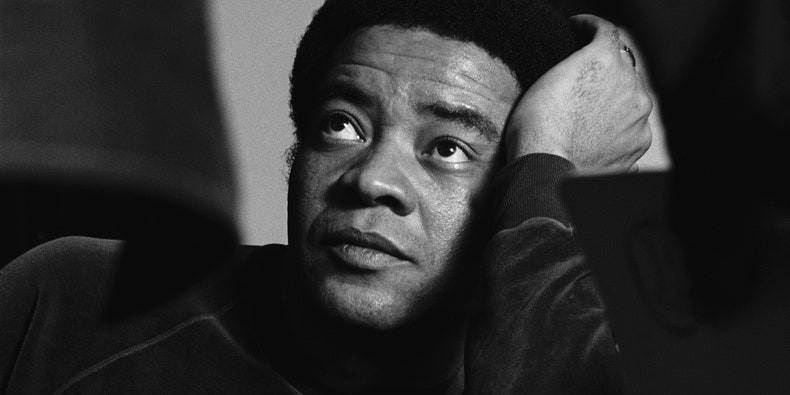

When the great singer-songwriter Bill Withers died of heart failure on March 30, 2020, he had been retired from what he called “the fame game” for 35 years. He was born in the tiny mining town of Slab Fork, West Virginia (pop. 200), on Independence Day 1938, the youngest of six kids. As a young adult he’d supported himself and his family with a series of blue-collar jobs and a nine-year stint in the Navy, stationed mostly in Southeast Asia. A professional music career wasn’t on his list of plans.

When the great singer-songwriter Bill Withers died of heart failure on March 30, 2020, he had been retired from what he called “the fame game” for 35 years. He was born in the tiny mining town of Slab Fork, West Virginia (pop. 200), on Independence Day 1938, the youngest of six kids. As a young adult he’d supported himself and his family with a series of blue-collar jobs and a nine-year stint in the Navy, stationed mostly in Southeast Asia. A professional music career wasn’t on his list of plans.

On the cover of his 1971 recording debut Just As I Am, for the indie Sussex label, he was photographed on break outside his employer, Weber Aircraft in Burbank, California, holding his lunchbox. Withers was still working there as an airline mechanic, mainly installing toilets, when a song from the album, “Ain’t No Sunshine,” became a pop hit and rightly elevated him to the company of Stevie Wonder, Al Green, Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield. “I’m not a virtuoso,” he said in his speech of induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2015, “but I was able to write songs that people could identify with.” Typically for such a humble man, that was a huge understatement.

Withers had always enjoyed the varied music he heard in church, on the radio and in nightclubs in West Virginia, whether country, folk, blues, pop, gospel or soul, and when he started messing around with his own songwriting in his 30s a blend of styles came naturally. As he told a PBS interviewer in 2007 when he was inducted into the West Virginia Music Hall of Fame, in highly segregated Slab Fork his household was one of the few Black families to live just barely on the “white side” of town, over the railroad tracks that divided the population along racial lines. He tried to downplay his experience of racism: “When you come out of the coalmine, everybody’s black,” he ruefully joked.

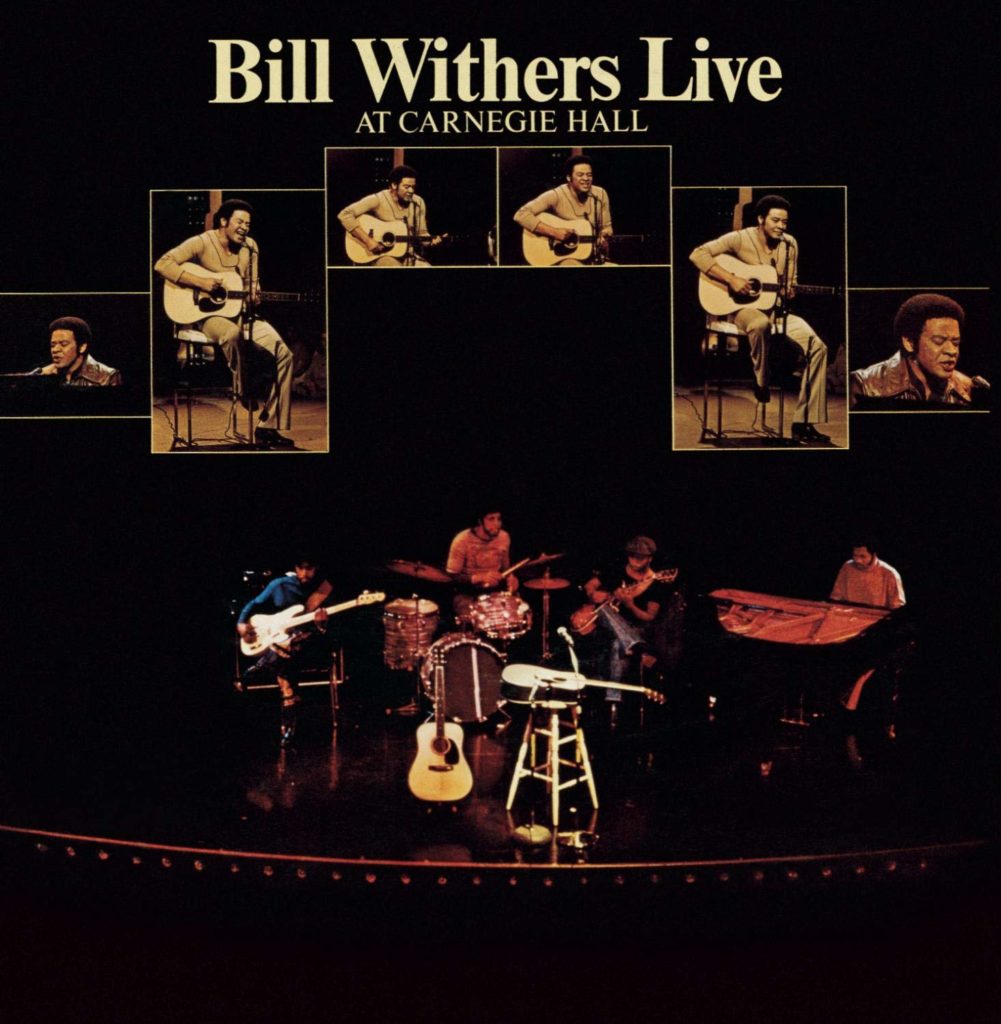

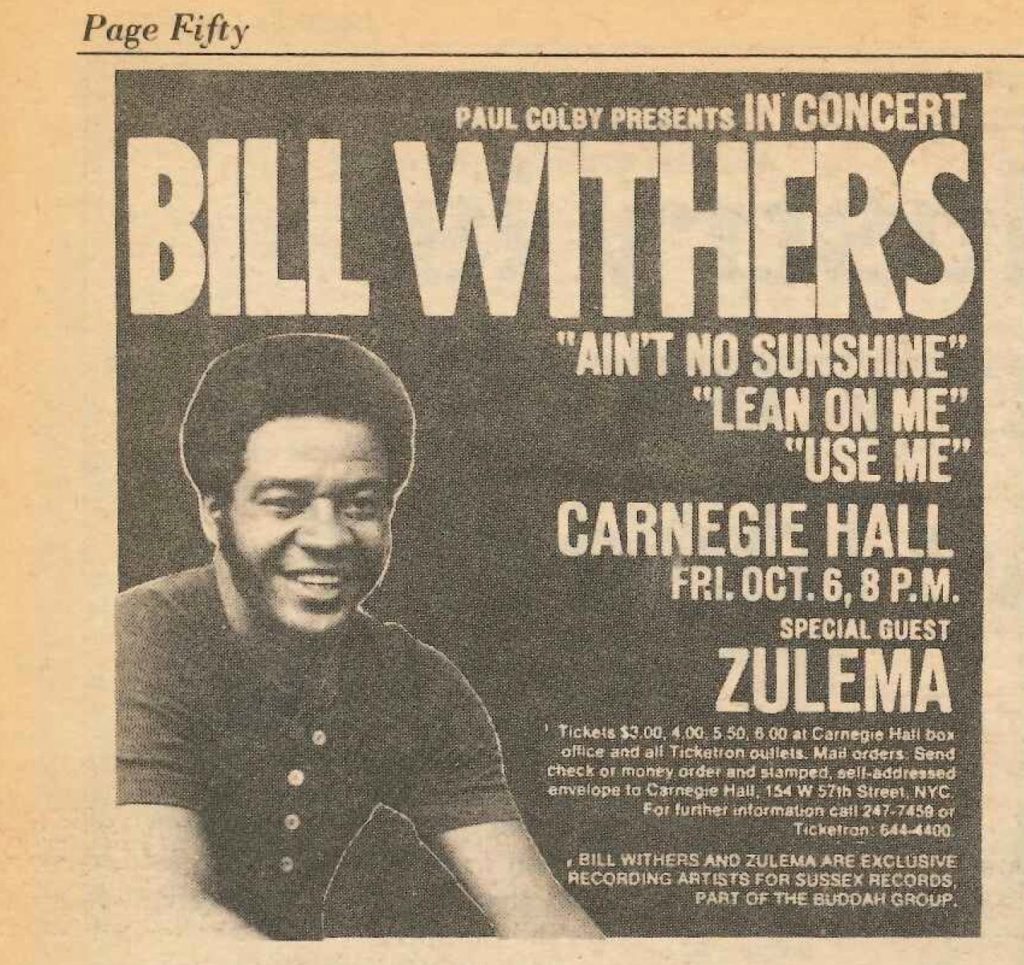

The passionate tribute “Grandma’s Hands” followed “Ain’t No Sunshine” up the pop charts, and he was nominated for several Grammy Awards, with “Ain’t No Sunshine” winning for Best Rhythm & Blues Song. The following year his second album, Still Bill, contained even bigger hits, “Lean on Me” and “Use Me,” bringing higher live performance fees and the chance to play prestigious venues; when he stepped on stage at Carnegie Hall Oct. 6, 1972, Sussex was recording the sold-out show for a live double-LP.

Withers played acoustic guitar with a subtle touch, and had developed a remarkable sympathy with his touring and recording band: keyboardist Ray Jackson, Bernorce Blackman on electric guitar, bassist Melvin Dunlap and drummer James Gadson (supplemented for the Carnegie Hall gig by well-known studio percussion ace Bobbye Hall). “I’ve never been so excited in all my life,” Withers wrote about that night in the liner notes to Live at Carnegie Hall, which was released on April 21, 1973. “In about an hour and a half that audience transformed us all from nervous, serious musicians into free and happy people.”

Related: When Bill Withers ‘punk’d’ the USC Trojans football team

The show begins with the high-energy groove of “Use Me,” driven by Jackson’s clavinet and Gadson’s super-funky rim-shot drumming. The audience is clapping along on the offbeat, Blackman wails on wah-wah, and Withers preaches, exhorting the crowd and the band. There’s a false ending, and several more minutes of hard funk. He speaks for every love-crazy man whose friends tell him he’s being “used” when he sings to his woman, “I wanna spread the news/That if it feels this good getting used/Oh, you just keep on using me/Until you use me up.”

Withers immediately changes pace with the lighter, previously unrecorded “Friend of Mine,” which is beefed up with strings and horns dubbed onto the master tapes later at the Record Plant in Los Angeles (most of the tracks have similar overdubs).

The crowd hushes for a solid “Ain’t No Sunshine” and laughs along with Withers’ joking but heartfelt introduction to “Grandma’s Hands.”

Another new song, “World Keeps Going Around,” is led by the acoustic and electric guitars intertwining. The lyrics tell a story through various characters, and contain, as many of Withers’ songs do, homespun philosophy: “Lookin’ at the pictures of the places/That he’d been, an old man told me what he’d found/Said it don’t make no difference whether you’re/Out or whether you’re in/The world keeps goin’ round and round.”

The love ballad “Let Me in Your Life” from Still Bill is given a sensual, easy interpretation (again, the overdubbed strings help set the bittersweet atmosphere). Withers’ vocal is quite extraordinary, a combination of Johnny Mathis and Al Green. He follows with the gritty “Better Off Dead” from his debut album, and his charisma is in full flower as the band absolutely cooks behind him (listen to how locked in the bass, guitar anddrums are).

Hall’s percussion is perfect in another new tune, “For My Friend,” which also features more silky wah-wah from Blackman and a typically direct and confident vocal from Withers. It closes out the first disc of the two-LP set.

“I Can’t Write Left-Handed,” a Withers-Jackson co-write, was never issued on any Withers studio album, although in his intro he makes mention of having recorded it. This is perhaps the most outstanding performance from Live at Carnegie Hall, recalling the power of Marvin Gaye’s contemporary What’s Going On disc. A brooding backing chorus lays down a gospel bed, Jackson provides the sanctified block chords and Blackman the tasty, restrained lead guitar. Withers intones the lyrics, about an amputee soldier, with controlled fire: “I can’t write left-handed/Would you please write a letter/Write a letter to my mother?/Tell her, tell her to tell the family lawyer/To try to get a deferment for my younger brother.”

The audience is clearly enthralled, and as Withers launches into “Lean on Me,” they clap along and shout encouragement. Listen for Hall’s tambourine accents during the first simply arranged verses, and the way the chorus explodes with epic emotion. Withers likes how the audience sings along so much, he asks them for an encore. (OK, no doubt Withers learned to build such “spontaneous” moments into his stage show, but even so it seems totally genuine.)

The choppy funk of “Lonely Town, Lonely Street” follows, with overdubbed horn parts that sound right out of Memphis’ Stax or Hi studios. Withers absolutely swings the vocal, roughing up his voice for a more Wilson Pickett-type sound. “Hope She’ll Be Happier” from his first album follows. It’s a tremendously sad lament, with a pain-filled vocal from Withers: “Maybe the darkness of the hour/Makes me seem lonelier than I am/But over the darkness I have no power/Hope she’ll be happier with him.” As Withers stretches out some notes and clips others, you can imagine Sinatra singing it.

Another song unavailable elsewhere, “Let Us Love,” has echoes of the Staple Singers and Sam Cooke. Blackman’s meat-and-potatoes solo fits right into the gospel vibe. In the last couple minutes, it kicks into double-time as a horn section cooks.

The album concludes with a 13-minute medley of “Harlem” (the lead-off track to Withers’ debut LP) and “Cold Baloney,” a Withers song previously recorded by the Isley Brothers. To start, Hall is on congas while Jackson lays down the ascending piano chords and Withers absolutely wails out his heart, his Southern accent delightfully bending “par-tay.” You can visualize him roaming the stage as he sings, “I’m home all by myself/Just five years old, and sho’ is cold/Mama cookin’ steak for someone else.” It all evolves into a call-and-response with the audience that’s pure joy.

Upon release, the album was favorably compared to such landmarks as Aretha Franklin’s Live at Fillmore West and James Brown’s Live at the Apollo. In 2015, Rolling Stone ranked it among the best 50 live albums of all time. Withers followed it with his last Sussex album, the ambitious +’Justments, before jumping to Columbia Records for big bucks, and finding he didn’t fit in there; he called their A&R department “antagonistic & redundant.” He only hit the top 20 one more time, as vocalist on Grover Washington Jr.’s “Just The Two of Us” in 1981.

Withers’ five Columbia albums failed to make any waves, and he felt more and more alienated from an industry that was too much business and too little music. He walked away in 1985, and even as hip-hop artists praised and sampled him, and his early back catalog continued to sell, he was never lured back. During his years away from the spotlight, several artists organized concerts honoring his legacy, and a documentary film, Still Bill, arrived in 2010. The singer José James’ issued an excellent tribute album, Lean on Me, in 2018. Withers participated in his Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction, but if he was recording anything new he didn’t share it, no matter how cordial he continued to be during interviews and non-performing events.

“One of the things I always tell my kids is that it’s OK to head out for wonderful, but on your way to wonderful, you’re gonna have to pass through all right,” Withers was fond of saying. “When you get to all right, take a good look around and get used to it, because that may be as far as you’re gonna go.”

The album is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Bonus Video: Bill Withers, Stevie Wonder and John Legend perform “Lean On Me” at Withers’ 2015 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationThe story before “Grandma’s Hands” always makes me laugh.