The Beatles filming “Revolution,” September 4, 1968 (Photo © Apple Corps Ltd.; used with permission)

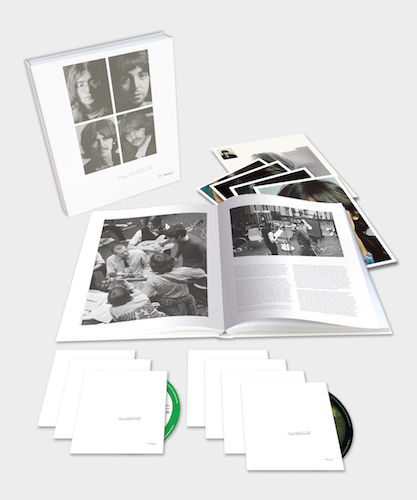

2018’s Super Deluxe 50th anniversary edition of The Beatles, a.k.a. The White Album, was a deep behind-the-scenes look at how that 30-song, double-album masterpiece came to be. It’s been a trope since the album’s U.K. release, on Nov. 22, 1968, that the White Album—so nicknamed because its cover was all-white, save for a stamped serial number on each LP produced in the early pressings—was the sound of The Beatles dissolving. That’s true to a great extent—many of its tracks are the work of a sole Beatle or partial-group performances.

But other tracks, and much of what we can now hear on the six-CD (plus Blu-ray) Super Deluxe commemorative edition, display a quartet that still enjoys making music together—and takes the group quite seriously (some songs required dozens of takes in the studio until the band was happy with one). At the same time they were maturing, they were preparing to leave behind the phenomenon that was the Beatles.

The history has been meticulously documented: the arrival of Yoko Ono into John Lennon’s world: the group’s time together at the Indian meditation compound of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, where several of the White Album’s songs were written; Ringo Starr’s decision (short-lived) to walk out on the group. It’s all spelled out in vivid detail in the comprehensive, lavishly illustrated hardcover book that houses the CDs that comprise the Super Deluxe.

Related: The Super Deluxe edition immediately topped the sales chart

The music on the original White Album is, like all of the Beatles’ output, the product of a very specific time; the new anniversary releases (also available in abbreviated standard and deluxe editions) aim to put it into context. In addition to the music of the original album, newly mixed by producer Giles Martin (the son of original Beatles producer George Martin) and Sam Okell in stereo and 5.1 surround sound, the Super Deluxe includes the 27 so-called Esher Demos: early, stripped-down working versions of songs that would appear on the album plus others that would find their way to other projects (including Abbey Road and solo albums). It also includes 50 session recordings of in-progress and outtakes galore. They are, to be sure, a revelation.

The Super Deluxe, like the similar treatment afforded Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely hearts Club Band in 2017, is nothing less than fascinating; even fans who have owned the bootleg releases containing much of this music will savor the enhanced audio and newly discovered tracks that populate the six discs. There are in-studio jams, rehearsals, instrumental backing tracks, drastically different and unfinished lyrics and so much more.

For all of the excitement and revelation generated by the expanded releases though, in the end there remains—to paraphrase from the landmark they released the previous year—the album we’ve known for all these years. We gave it a fresh listen and noted some of the more intriguing fragments of information regarding each track.

Back in the U.S.S.R.

One of many songs on the album written (this one by Paul) during the Beatles stay in Rishikesh, India, to study Transcendental Meditation with the Maharishi, the Beach Boys tribute/parody was recorded without Ringo, who had temporarily left the group due to what he said was criticism of his drumming. The song includes a mention of the Hoagy Carmichael composition “Georgia on My Mind,” included by Paul because the nation of Georgia was part of the Soviet Union at the time. Minutiae: The airplane sound effects are different on the mono and stereo versions.

Watch the lyric video for “Back in the U.S.S.R.”

Dear Prudence

Prudence Farrow, sister of actress Mia Farrow, was one of the Westerners meditating in India with the Maharishi the same time the Beatles were there. She was being reclusive, and John wrote the song to try to convince her to “come out and play.” The song was recorded sans Ringo, who was into his brief departure from the band. Sean Lennon later covered the track, as did Jerry Garcia, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Leslie West, Alanis Morissette and others.

Glass Onion

John refers to five other Beatles tunes in his lyrics: “I Am the Walrus,” “The Fool on the Hill,” “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “Fixing a Hole” and “Lady Madonna.” John later said that his line “The walrus was Paul” was a joke. Glass Onion was also a name suggested by Lennon for a new band originally called the Iveys that signed to the Beatles’ Apple label. They chose Badfinger instead.

Listen to an early studio take of “Glass Onion”

Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da

The title comes from an expression Paul heard spoken by Nigerian conga player Jimmy Scott-Emuakpor: “Ob-la-di, ob-la-da, life goes on, brah.” John reportedly hated the song and some fans must agree because it’s been named among the worst songs ever in several music polls. Nonetheless, the song, which took on a Jamaican ska-influenced rhythm after much studio experimentation with the tempo, was released as a single in some countries and topped the charts in Japan, Australia and a few others. That conga player, by the way, later tried to sue the Beatles for royalties—he did not prevail.

Wild Honey Pie

The recording lasts less than a minute and feels like something tossed off in the studio, which it basically was: Paul wrote it and is the only performer on the track, contributing all of the vocals and instruments. Most of what you hear in the background is a harpsichord.

Related: Our interview with Giles Martin on the White Album 50th anniversary releases

The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill

Another Lennon composition stemming from the Rishikesh visit, this one was inspired by John’s scorn for Richard Cooke III, a wealthy American college student who was present at the Maharishi’s ashram and went out on a tiger-hunting caravan. The little flamenco guitar line heard at the song’s start was actually played on a Mellotron by studio engineer Chris Thomas.

While My Guitar Gently Weeps

No big secret that the lead guitar, uncredited on the album, was played by George’s friend Eric Clapton. Harrison wrote the song after returning from India and recorded an acoustic demo. The other Beatles were not all that impressed with it at first, perhaps because the lyrics partially reflect the disharmony that was brewing with the group. Upon the album’s release, and ever since, the track—one of four by Harrison on the White Album—became one of the band’s most popular.

Listen to the Esher demo of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”

Happiness is a Warm Gun

Considering how we lost John, it’s chilling to think that he wrote this song after seeing the title on the cover of a gun magazine. (What might be even more stunning is that the gun magazine was playing off the Peanuts cartoon’s phrase, “Happiness is a Warm Puppy.”) The track is one of few on the album that features the traditional Beatles configuration of John and George on guitars, Paul on bass and Ringo on drums, without any additional instrumentation or outside help.

Martha My Dear

It was written by Paul for his Old English Sheepdog, Martha, although some accounts have McCartney’s ex-girlfriend Jane Asher being the real inspiration (the lyric “You have always been my inspiration” was said to be the giveaway). John and Ringo do not appear on the recording.

I’m So Tired

John missed Yoko Ono terribly while he was in India for the meditation retreat, and wrote this ballad while unable to sleep. The nonsensical mumbling at the beginning of the track is actually John saying, “”Monsieur, monsieur, how about another one?” Some fans, however, misheard it as a masked reference to Paul being dead, fueling a rumor that McCartney had died and been replaced by a look-alike/sound-alike.

The Beatles with George Martin during a recording session at Trident Studios. 1968. (Photo: Tony Bramwell / © Apple Corps Ltd.; used with permission)

Blackbird

Paul wrote and recorded this solo after hearing a blackbird while in India. But he has long said that it actually refers to the Civil Rights movement in America at the time. The recording consists entirely of Paul’s acoustic guitar, double-tracked vocal and foot-tapping, as well as the sound of a blackbird singing. McCartney has performed the song during every tour he’s done since going solo. Among the many cover versions is a beautiful harmony-rich take by Crosby, Stills and Nash.

Piggies

One of the four George Harrison-penned numbers on the album, “Piggies” was meant as social commentary—the word pig, at the time, referred to both a police officer and any “Establishment” type who was deemed to be greedy or ultra-conservative. Many found the song somewhat humorous, but one person who did not was Charles Manson, the California-based cult leader who believed the Beatles were speaking directly to him. Manson interpreted the song’s lyrics as a call for him to start a race war. When his followers committed their notorious murders, they wrote the word pig in their victims’ blood on the walls.

Rocky Raccoon

Paul’s attempt to write a cowboy song about a near-fatal love triangle began at the Rishikesh ashram. The piano on the recording was played by producer George Martin. Donovan, also present at the ashram, is said to have had some part in writing the song but was not credited.

Listen to one of McCartney’s early takes

Don’t Pass Me By

This was Ringo’s first solo composition for a Beatles album but it was not new when he cut it with the group in 1968. In fact, “Don’t Pass Me By” dates all the way back to 1962, to shortly after the time he joined the band. The lyrics certainly underwent some changes over the years though, and the bizarre line “I’m sorry that I doubted you, I was so unfair, you were in a car crash and you lost your hair” was later cited as another clue by the conspiracy theorists who spread the “Paul is Dead” rumor, as McCartney had supposedly died in a car crash. Ringo and Paul are the only Beatles on the track—the wild violin solo was contributed by Jack Fallon, a British jazz musician.

Why Don’t We Do It In the Road?

Less than two minutes long, it was written by Paul after he witnessed two monkeys having sex in the open in India. Other than Paul, Ringo is the only musician on the track.

I Will

There is no bass on this tune—Paul (who wrote it) supplies “vocal bass” instead. There is also no George Harrison on this all-acoustic song: Paul plays nearly everything except for some percussion from Ringo and John. Despite its simplicity, the Beatles did 67 takes of the song. During take 19, Paul improvised a bit that’s come to be known as “Can You Take Me Back?,” half a minute of which was later excised and included on the album between “Cry Baby Cry” and “Revolution 9.” (You can hear the full tune now on the Super Deluxe White Album.) “I Will” has been covered by everyone from Diana Ross to Phish to Art Garfunkel.

Julia

John is the only person who appears on the song, which was written about his late mother while the Beatles were in India. John employs a finger-picking acoustic guitar style he learned from singer Donovan. The phrase “ocean child” in the lyrics was, however, a nod to Yoko Ono, whose Japanese last name translates to Ocean Child. The opening line is taken directly from the poem “Sand and Foam” by Kahlil Gibran, which reads (in the original version), “Half of what I say is meaningless, but I say it so that the other half may reach you.”

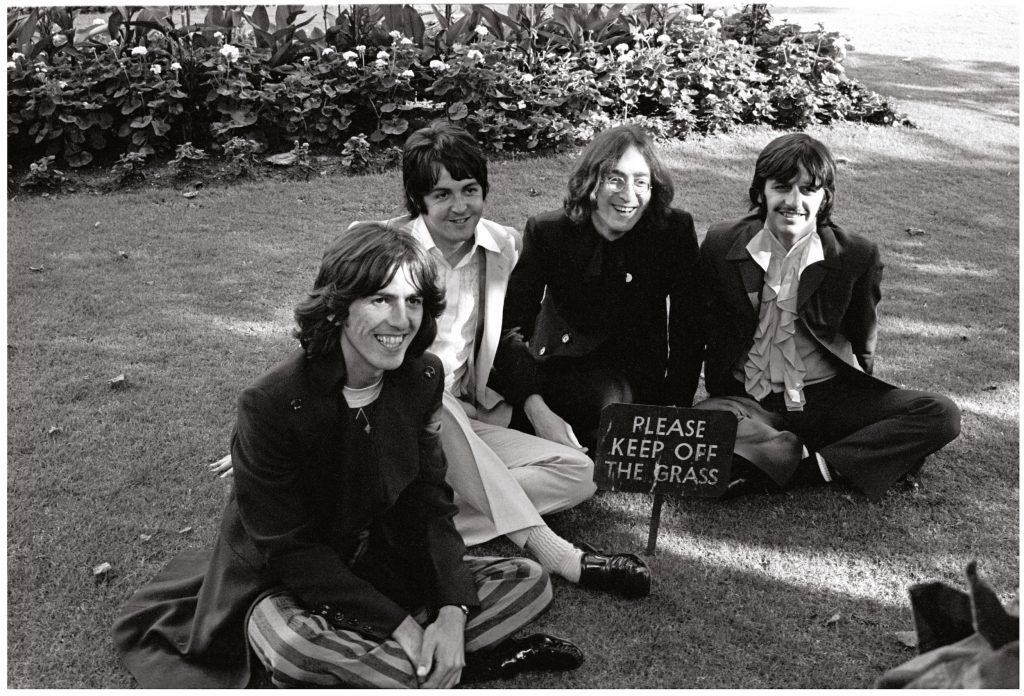

The Beatles at St Pancras Old Church, London, July 28, 1968 (Photo © Apple Corps Ltd.; used with permission)

Birthday

One of the rare instances of a song truly co-written by Lennon and McCartney (although mostly by Paul) in the latter Beatles years, “Birthday” was composed in Abbey Road Studios. Both Yoko and George’s wife Pattie contributed backing vocals to the track.

Yer Blues

Another one from the India stay, it was written solely by John, who also sings the lead vocal. A basic blues progression, given a deliberate hard edge by John, it was recorded by the four Beatles in their original, basic guitar-bass-drums format sans additional instrumentation or personnel. John performed the song on the Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus concert with Eric Clapton, Keith Richards and the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Mitch Mitchell.

Mother Nature’s Son

Paul is the only Beatle on this acoustic beauty, with a brass arrangement by George Martin. The bongos-like sound was achieved by Paul playing timpani and bass drum at the far end of the studio so that the microphone dulled the sound. Among the cover versions: Harry Nilsson, Sheryl Crow, John Denver and jazz artists Ramsey Lewis and Brad Mehldau (separately).

Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey

One of the more raucous songs on the album, John wrote it (as he did so many songs) about Yoko. Some have commented that the song was about heroin, which the couple admitted using, but Lennon denied that.

Sexy Sadie

John’s song was a thinly veiled critique of the Maharishi, with whom Lennon had become disillusioned. In fact, an original draft of John’s lyrics was filed with all sorts of obscenities directed at the guru. One of the surviving original lines, “What have you done?/You made a fool of everyone,” was inspired by a verse in a song by Smokey Robinson and the Miracles.

Helter Skelter

Probably the Beatles’ “heaviest” song, and often considered an influence on the developing metal genre, the fierce, raw McCartney-written rocker, has, unfortunately, become as closely associated with the Manson murders as with the Beatles—the murderous cult leader somehow interpreted the song to mean that he was to start a race war in the United States. A book on the Manson “family” took the title of the song as its own. McCartney has since re-embraced the song and includes it in his concerts to this day. That’s Ringo you hear at the end, shouting, “I’ve got blisters on my fingers!”

Listen to a significantly longer early bluesy take of “Helter Skelter”

Related: Our feature story on the “punishing, Hell-for-leather” second take of “Helter Skelter”

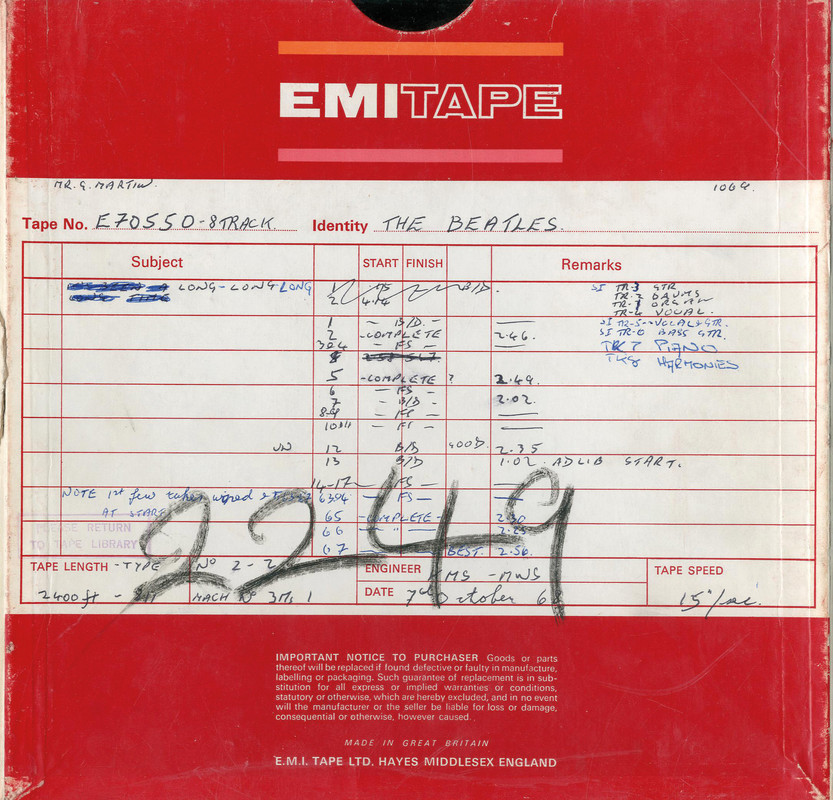

Long, Long, Long

This folkish, placid, ethereal tune was penned by George in Rishikesh and, he said, was addressed at God, although it could also be interpreted as being directed toward a missed ex-lover. John sat this one out while Paul provided the Hammond organ as well as the bass, with engineer Chris Thomas playing piano and Ringo, of course, on the drums.

Revolution 1

The Beatles recorded three “Revolution” songs in 1968: “Revolution 9,” the avant-garde sound collage; the un-numbered, hard-rocking “Revolution,” released as a single; and “Revolution 1,” a bluesy, slowed-down, shuffling version. That’s the one that appears on the White Album and, like the single, it found John expressing empathy with the revolutionary fervor of the tense time while simultaneously cautioning against violence. While Nicky Hopkins added piano to the single version, he’s not on the album cut, which instead includes horn players and backing vocals.

Listen to an expanded version of “Revolution 1”

Related: The “Revolution” video

Honey Pie

Paul, whose father led a jazz big band, always harbored an appreciation for the British music hall style, and “Honey Pie,” which he wrote, is a direct tribute to the form. At one point the staticky crackle of a 78 RPM record was added to give the song an old-time feel. Although the others weren’t quite as enamored of the old music as Paul, they each played on the track, as do a team of horn men, including one George Martin on sax and clarinet.

Savoy Truffle

What might have been a throwaway from anyone else—the soul-flavored song was written by George and inspired by Eric Clapton’s love of sweets—becomes a compelling tune in the Beatles’ hands. John takes a break from this session, and in addition to Ringo and Paul, a six-piece horn section and Chris Thomas on keyboards boosts up the sound. Strangely enough, Ella Fitzgerald once covered the tune.

Cry Baby Cry

This somewhat haunting number was written by John, with playing input from the other three plus George Martin on the harmonium. On the album, it’s followed by the brief uncredited snippet by Paul, “Can You Take Me Back?,” which actually originated during a jam session that arose out of one of the takes for “I Will.”

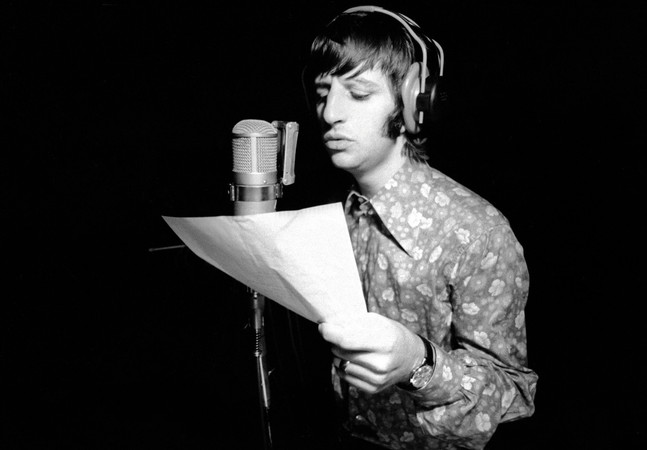

Ringo Starr during a recording session for The Beatles. Abbey Road Studios. June 1968.

Credit: © Apple Corps Ltd.

Revolution 9

The most controversial “song” on the White Album, the experimental “Revolution 9” was John’s creation, influenced heavily by Yoko. Paul and Ringo are nowhere to be found, but George was involved, contributing some guitar, vocals and sound effects. Ono can also be heard on the track. Largely constructed around tape loops and other snippets of sound, the audio collage has been interpreted in many different ways. Lennon said at the time that it was about death, but he discounted that explanation later and said it was just a collection of unrelated sounds. The spoken word snippet at the beginning is Alistair Taylor (late manager Brian Epstein’s personal assistant) saying to George Martin, “I would’ve gotten claret for you but I’ve realized I’ve forgotten all about it, George, I’m sorry. Will you forgive me?”

Good Night

Ringo Starr, as the singer, is the only Beatle who appears on the track, which features a full orchestra arranged and conducted by George Martin. John wrote the lush ballad for his son Julian, who was five at the time. The final words on the White Album are, “Good night. Good night, everybody. Everybody, everywhere. Good night.”

Listen to a substantially different early take of “Good Night,” sans orchestra

The 50th anniversary edition is available in the U.S./worldwide here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Giles Martin and Sam Okell discuss the project

6 Comments so far

Jump into a conversation50 years later, I finally know what a “Helter-Skelter” really is. Give the boys credit: they could take just about anything and make a compelling song out of it.

Oddly (and unfortunately, in my opinion), you comment on Helter Skelter’s undying association with the Manson family. If no one [but Manson] is pleased with this association, then simp[y stop making it. There is enough merit to the song that it doesn’t need to be constantly tied to tragic circumstances.

the media made up the manson helter skelter rumor.Manson never said anything about it

I always thought Helter Skelter was the name of a new roller coaster that was pretty well death defying. Ah, well. I finally bought this last year and it is a fun listen. I like John’s insertion on Paul’s “I Will.” Yes, this could have been one album, but it was a huge event in 1968 with the Beatles pulling out all the stops to make a double. A single disc would have all 4 Beatles on each track, not just one or two.

To my mind, the word “Masterpiece” relates to a unified artistic vision that is skillfully created with precise forethought, As many Beatles fans as there are who consider “The White Album” to be their favorite Beatles album, I always considered it more of a compilation of diverse individual ideas than it was a record made with a unified vision as a group. In that respect, I have come to think of the White Album as the record that actually represented the beginning of the end of the Beatles, rather than the often maligned “Let It Be,” which was basically a matter of pretty much already kicking a dead horse. On top of that, to my ears, the consistency of the White Album’s sonic quality varies greatly, especially in comparison to most of their other records. Some tracks sound almost more like demos than they do finished recorded works by the world’s most renowned pop group of the past century. It’s been endlessly argued by many that the White Album could have/should have been condensed into one truly great album, rather than given way to its sprawling excesses and experimentation. While it’s those same somewhat questionable tracks that some feel should have been eliminated that other fans insist that the album receives its personality and shows the Beatles at their most artistically wide-ranging. The record has so many ongoing diverse opinions about it, all of them valid to varying extents, and all of them subjective, as art is meant to be. For these reasons, I can’t agree that The White Album is a “masterpiece,” and certainly not their definitive masterpiece, if there actually is one record of theirs that can actually be ordained with that title. As for myself, I own their whole catalogue (primarily the British versions of their records at this point), and I’ve listened to it backwards and forwards for so many years now, in addition to regularly listening to the Beatles Channel on Sirius XM, and while I have lived through various times where different albums and points of their career have become my favorite for a period of time, I think I’ve finally come around to accepting that my actual favorite Beatles album, if indeed there must be just one, would actually have to be Magical Mystery Tour, for a variety of reasons. But that’s a whole other topic that requires a whole other discussion.

Even better i bought a Japanese copy of the “White Album’ with lyrics in both Japanese & English & plastic inner sleeves with a total of 37 tracks