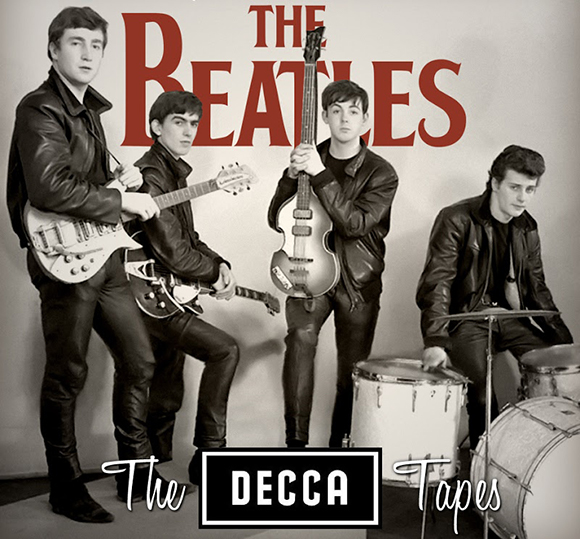

The Beatles’ Decca Audition: An Invaluable Lesson in Failure

by Colin FlemingThere are times in a listening life when one wishes that a particular recording in question might be a grail in plain view. That is, an album, session or concert which can be easily accessed that may reveal itself as a treasure of sublime artistry that most everyone has somehow managed to miss or undersell.

The Beatles have a number of recordings of the grail-in-plain-view variety, but there’s one in particular that even a longtime Beatles fan is apt to return to again and again, hoping that they’re struck in a way that they weren’t previously, in all likelihood.

That recording is the famed—or infamous—audition tape that the band made for Decca Records on the very first day of 1962, The Beatles’ final pre-fame year. In reading of their story, one is led to believe that these four men endured much and put in a mountain of dues before the breakthrough moment, but we’re only talking a handful of years, hardly the kind of odyssey in search of success that someone like Van Gogh experienced, with the breakthrough happening only after he’d taken canvas and brush to a different astral plane.

But in a society now where people often give up very soon—if they ever really got started—unless they’re handed what they think ought to be given to them, the Beatles’ attempt to land a record deal can resonate as a gargantuan struggle.

We mustn’t be misled because of devolving standards regarding perseverance. The Beatles had a number of factors on their side in their incipient stages, but in terms of getting underway professionally, nothing was bigger than timing.

Would the Beatles ever have been anything if they were the lone guitar band in the United Kingdom, even if they had their best material ready to go? The Beatles were abetted by having a wave of bands ready to roll with them. There were groups of all kinds of stripes and abilities. But a veritable beat army was in place, and being a band within those considerable ranks meant that there was a great chance you’d get your chance.

What you did with it would come down to a number of factors—talent, songwriting, vision, luck, support. The Beatles had all five, though presumably the first three would have been enough.

Related: This same author reappraises the Beatles’ cover of “Mr. Moonlight”

The Decca tape is usually among the first unreleased Beatles recordings that fans are likely to hear or acquire. They are a cornerstone of a gap-free Beatles collection, and any reasonably comprehensive understanding of where this band was at during a crucial period of their ascent.

Had the Beatles not done a lot of what they did in 1962—starting with the Decca audition—and made certain decisions and adjustments as they went along, then the rest of what we think of as being inevitably Beatlesesque doesn’t happen. Or at least not as it did.

On January 1, 1962, Paul McCartney had been the bass player of the Beatles for half a year, taking over after Stuart Sutcliffe stayed behind in Germany after the band’s latest Reeperbahn residency. Pete Best is the drummer. Brian Epstein is the manager. In mid-December of the previous year, Decca A&R man Mike Smith attended a Beatles gig at the Cavern. Their hope was that he’d offer them a record deal on the strength of their performance, but Smith wasn’t completely convinced.

This didn’t augur well for the Beatles—tearing it up at the Cavern was their thing, a place where they felt comfortable, had support, and whose acoustics helped hide what was better left hidden. The Beatles were an energy act. It takes time to extrapolate the energy a band might have on stage to a comparable energy in the studio, and the Beatles just hadn’t had it yet.

The quartet was invited to Decca’s studios in London on New Year’s Day, where they’d be put through their paces and then the powers that be would see where matters stood.

Huddling into Neil Aspinall’s van on that all-important snowy winter morning, with Epstein voyaging by train—because it wasn’t like he was going to pile in with the bodies and instruments—the group barely made it from Liverpool in time for their 11 a.m. appointment.

Still, this was more than can be said for Smith, who was late after a night of doing what most people do on New Year’s Eve. Worse was when Smith told the group that their equipment wasn’t up to par and directed them to use Decca’s gear instead.

Things tend not to go well when a band has to play with equipment that isn’t their own. If you listen to the Who doing just that at Monterey in 1967, you hear a diminished attack from a band that itself was ordinarily a kind of sonic army, or at least specialist operation. The Beatles were nervous to begin with, and now they were further unnerved. But as they say, the show goes on, even the audition show.

Some cuts from the Decca audition have spilled out officially over the years, courtesy of the first Anthology, but they’ve never been that difficult to track down in full, and with the internet it’s easier than ever. To get a sense for what went down that morning, the complete tape is needed.

The Beatles—with Epstein’s input—clearly went with the conservative approach, figuring that lite pop and a familiarly with twee hits of the day would serve them well in the professional milieu of a “fancy” London recording studio. Thus, George Harrison singing Bobby Vee’s “Take Good Care of My Baby” in attempt to get it done, when John Lennon wailing his way through Little Eva’s “Keep Your Hands Off My Baby” would have been the much worthier approach.

Of the 15 numbers the Beatles performed, seven fall into that “What’s with all the soft rock?” category, with their covers of “September in the Rain,” “’Til There Was You,” “To Know Her is to Love Her,” “Besame Mucho,” and the aforesaid Vee tune; plus, the Lennon and McCartney originals, “Love of the Loved” and “Like Dreamers Do,” which were hard sells and why they didn’t revisit them later on.

Remember: “One After 909” got two kicks (six years apart) at being part of the Beatles’ canon on the back of its pluck and drive. If they saw value in a song, they’d return to tease that value out of it—which says a lot about the originals from this day.

McCartney always handled “’Til There Was You” with a certain professional grace, but you never have to hear it, even in its With the Beatles guise or what was a touching rendition on The Ed Sullivan Show.

“To Know Her is to Love her” would produce one of their finest cover performances on the BBC in July 1963, but that version had soul, whereas this one is limited by its rigidity. One senses that the Beatles are embarrassed, like they’re getting collectively undressed in front of a doctor.

It’s ironic that the Beatles—who would later make records with a producer in George Martin who oversaw comedy LPs—devoted two tracks at this audition to “humor hits” in “The Sheik of Araby” and “Three Cool Cats,” complete with John Lennon’s novelty voice, but they must have thought the way to a record deal was at least in partially through the funny bone. Problem was, neither performance proved risible in what was presumably its intended way.

Perhaps stranger still: a large chunk of the Beatles’ regular repertoire consisted of material made famous—or at least actually cool—by African-American musical artists, but the Decca tape feels very white, as if the Beatles didn’t want it to be known on that day what they really loved.

Yes, there are two numbers from the Coasters (albeit one is “Three Cool Cats”) and versions of Barrett Strong’s “Money (That’s What I Want)” and Chuck Berry’s “Memphis, Tennessee,” but the Beatles come off as a white band that wants to be seen as a clean-cut white band, which isn’t how they sound anywhere else.

With the Beatles, for example, is pure rhythm and blues, British beat rock-style. Even when the Beatles advanced beyond their influences, they came across as a band without borders or labels, and they certainly didn’t self-label, but that’s precisely what they’re doing here, while also attempting to show some range, though not their actual range.

Try to please everyone, and you please no one, including yourself. For the Beatles, January 1, 1962, was the day that the lesson was learned.

But all was not lost, even if Decca said, “Thanks but no thanks” to the future overhaulers of popular culture from England’s north. Pete Best was bad—as in entirely without flare and feel—and had to go. In March, the Beatles would tear through a BBC session and be none the worse for Best’s presence, but that’s because there was a stamping, well-into-it crowd to drown out the less effective bits as the voices and guitars—and the Beatles’ trademark energy—carried them through.

The best Decca number is Paul McCartney’s confident take on the Coasters’ “Searchin’.” He leans back into that vocal in a manner that allows him to properly belt it out, which is much the same technique he used to capture Little Richard’s “Kansas City/Hey-Hey-Hey-Hey” during the Beatles for Sale sessions in a single, thrilling take.

The Beatles are never less than pleasant throughout. You can listen to the Decca tape, and if someone said it was by this beat combo that showed promise and had a couple of singles that never went anywhere, you might mildly regret that they hadn’t progressed.

What we really have, though, is a day that produced an attitude adjustment. The Beatles had played to please others. They hadn’t trusted themselves or their own judgment. In sports phraseology, they had attempted not to lose. You don’t write “She Loves You,” or make A Hard Day’s Night, or compete with the Beach Boys of Pet Sounds if you’re not trying to win, which is a different prospect.

From this day forward, the Beatles were a band that would go for it, plain and simple. If they failed, it wouldn’t be because they had sat back and hoped for the best. No one who becomes the best at anything becomes so by hoping and contrivance.

The Beatles didn’t owe Decca anything or vice versa. Any competent A&R staff could have passed them over based on the results of that early afternoon, an opening salvo of reality to this new year that the Beatles soon made irrelevant.

Related: The Beatles at the BBC in 1963

Sgt. Pepper may have taught the band to play, but the Decca audition taught them how to win, and they obviously never forgot it.

Related: The same author’s feature on The Beatles’ recording of “I Saw Her Standing There”

The Beatles: 1964 U.S. Albums in Mono is available now in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here. Meet The Beatles!; The Beatles’ Second Album; A Hard Day’s Night (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack); Something New; Beatles ’65; and The Early Beatles are available individually here.

2025’s 12-LP and 8-CD editions of the Beatles’ Anthology Collection are available in the U.S./worldwide here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here. Anthology 4 is available as a standalone 3-LP or 2-CD set in the U.S./worldwide here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThe neat thing about those early recordings, is now you can hear them (the last clip for example) in stereo, thanks to digital extraction technology. You can hear the playing better without the vocals overwhelming the sound.

In a more raw form, you can even find the Star Club tapes in stereo. Pete’s drums take a back seat, and the vocals are distant. But George’s guitar comes through. As does John’s wonderful taunt, “If you can understand me . . . Piss Off!”

One of the very best Beatles articles I have ever read, very insightful, interesting, and thought-provoking. It has been a while since I’ve read something on the band that impressed me. Well done!

The conclusion of the story is exactly right. They sound like a garage band trying to impress, and coming out safe as milk.

One wonders what the reaction would have been if they were able to play an acetate of the music they recorded in Germany with Tony Sheridan a few months earlier. THAT band ROCKED.