‘Wichita Lineman’ Book: Exclusive Excerpt

by Best Classic Bands Staff

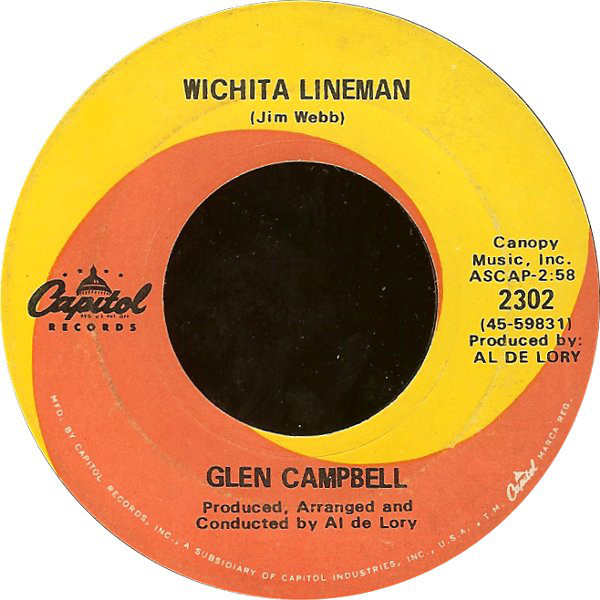

“Wichita Lineman,” recorded by Glen Campbell and written by “Jim Webb,” was released in October 1968

Jimmy Webb’s “Wichita Lineman” was first recorded in 1968 by Glen Campbell and is perhaps the song most closely associated with the singer’s remarkable career. It is also the tune that remains the standout among all of the classics from the long and successful collaboration of the composer and musician.

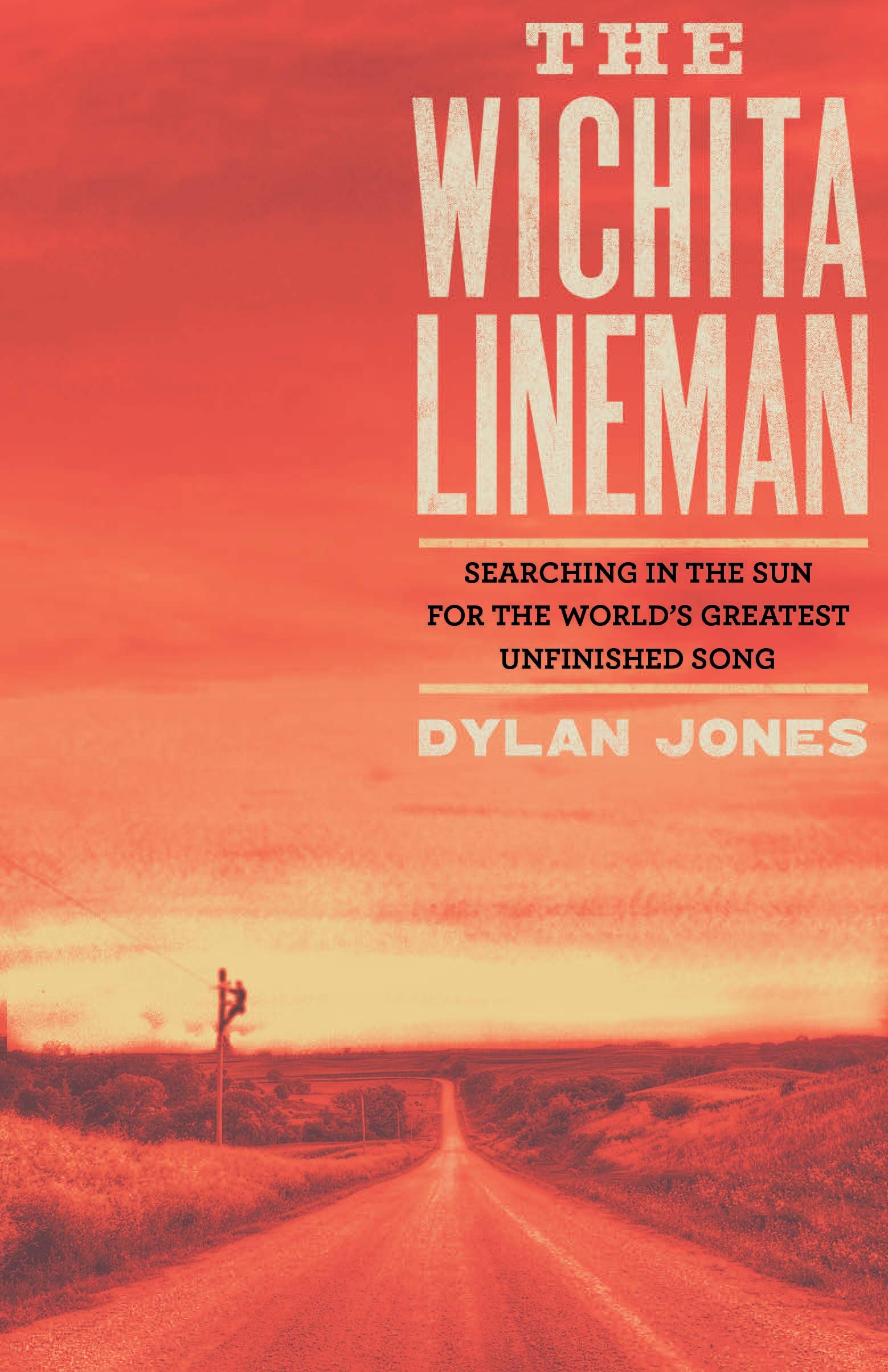

The song – as well as profiles of both Webb and Campbell – is the subject of a new book from author Dylan Jones, The Wichita Lineman: Searching in the Sun For the World’s Greatest Unfinished Song. The wistful tune is described in press notes as “the first philosophical country song: a heartbreaking torch ballad still celebrated for its mercurial songwriting genius 50 years later.”

Campbell recording the song with the legendary group of Los Angeles studio musicians known as the Wrecking Crew, of which he was perhaps its most famous alumnus. “Wichita Lineman,” released by Capitol Records in October 1968, with a songwriting credit to Jim Webb (as he was then known), became the singer’s second of five career #1 country hits and a #3 pop smash (in January 1969).

Best Classic Bands has an exclusive excerpt from Jones’ book, which was published in 2019 by Faber & Faber:

Best Classic Bands has an exclusive excerpt from Jones’ book, which was published in 2019 by Faber & Faber:

If you lived on Long Island in the seventies and someone said, “Meet me tonight in dream-land,” there was only one thing you were going to do, only one place you were going to go.

Back then, if you needed any litmus test as to who was about to cut through, wanted to find out which heavily touted newbie actually had real talent, you went to My Father’s Place, a 7,000-square-foot cabaret club in Roslyn, a historic village in Nassau County. U2 made their American debut here; in 1976, it was where the Ramones performed their most important out-of-town dates; and back in 1973, an aspiring Bruce Springsteen performed here to just thirty people. He loved the place so much he came back four more times, even after he became more famous than the club ever would be. Here, twenty-two miles from Manhattan, up-and-coming comedians like Eddie Murphy, Andy Kaufman and Billy Crystal made their starts. In an era when comedy and rock went hand in hand, if you wanted to break into either industry, My Father’s Place was where you came.

Early in 2018, the club [reopened] not far from the original venue, in the basement of the newly renovated Roslyn Hotel (formerly the Roslyn Claremont Hotel, but now reimagined as a boutique country inn), and six months later, in October, I came to have a look myself, or rather I came to see Jimmy Webb. Even though he lives not far from it, this was the first time he’d played the new venue, and it was something of a big deal for him. Webb regularly plays in New York, in London, in Sydney, all over the world. But there’s nothing like playing in your own backyard.

There were two hundred people in the club, all of whom had made a small pilgrimage to see the man known as America’s Songwriter, a man responsible for some of the greatest popular songs of the twentieth century, the Midwestern genius who wrote “Wichita Lineman,” “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” and “MacArthur Park,” the man who, in the space of a few months in the summer of 1968, became the most famous songwriter in America. All for $50 plus lunch.

And then he started, methodically making his way through his extraordinary collection of hits, an eclectic bunch of songs that are among the most successful ever recorded. Every time he got a hint of recognition from the crowd – and as so many of his songs are famous this happened every time his fingers returned to the piano – he smiled a big Liberace-type Midwestern smile of genuine warmth, demonstrating a little bit of old-school Vegas on Long Island’s North Shore.

Jimmy Webb (Photo: Sasa Tkalcan; used with permission)

Every night Jimmy Webb seems to get away with it, singing these famous songs he invented with as much passion and pathos as he probably did when he first wrote them; maybe with more, actually, as the songs have had time to wrap themselves in the misfortunes of experience. This afternoon he sort of slid his way through his tunes – almost walking–talking them like Burt Bacharach does – interrupting them with well-worn stories that mentioned everyone from Frank Sinatra and Richard Harris to Billy Joel and Kanye West, the somewhat legendary session guitarist Carol Kaye and, of course, his dear departed “brother,” Glen Campbell. He has become self-deprecating about his voice – “They don’t pay me as much when I sing,” he joked to the audience – and on a few of the songs he asked the crowd to join in on some of the tougher passages. Of course, what this meant was that today a further two hundred people could claim to have sung a song with Jimmy Webb.

By the time he got to “Wichita Lineman,” however, Webb’s voice had settled down to the extent that he performed it almost perfectly. Almost beautifully, in fact. He has never had the pipes his partner Glen Campbell had, but this afternoon Webb’s interpretation of his greatest song was just about as good as it could be, given the circumstances (the primary circumstance being the fact that the man who wrote it had just celebrated his seventy-second birthday). And as he carefully slowed the song down – moving down through the gears – the piano keys started mimicking the Morse code refrain that has always signalled the song’s finale, Webb’s fingers delicately tinkling over the horizon. This was close to a faultless performance, with Webb reach-ing for notes with his body as much as his voice.

Excerpted from The Wichita Lineman: Searching in the Sun For the World’s Greatest Unfinished Song by Dylan Jones. Published by permission of Faber & Faber. Copyright © 2019 by Dylan Jones. The book is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Jones is the author of the best-selling books, David Bowie: A Life and Jim Morrison: Dark Star. In 2013, he was awarded an OBE for services to publishing. He is currently the Editor-in-Chief of British GQ.

Related: Our interview with Jimmy Webb

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.