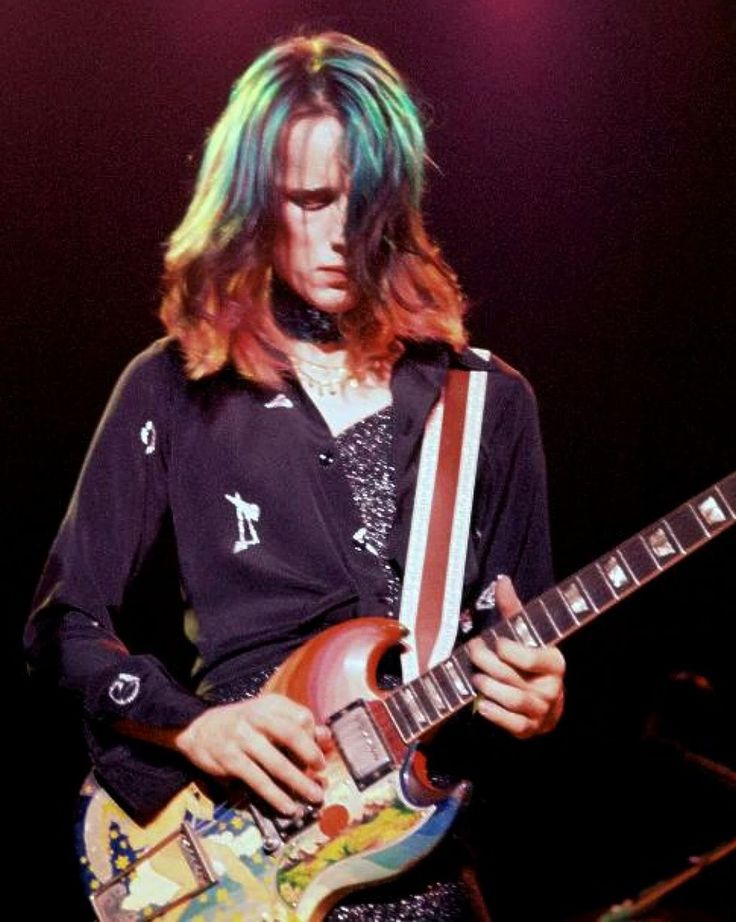

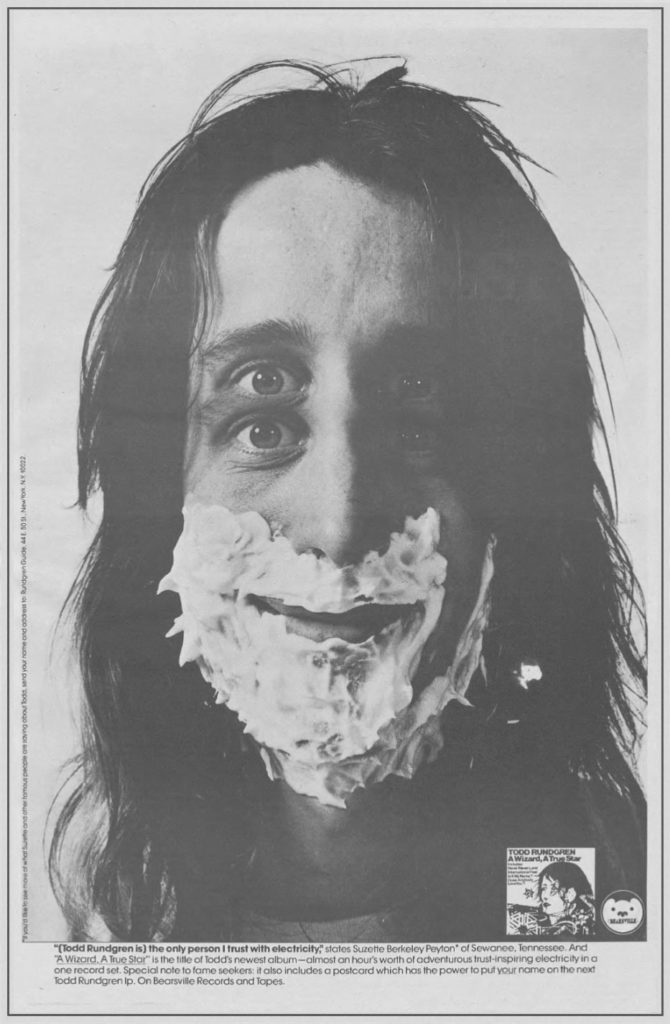

The use of hallucinogenic drugs had a profound effect on the music of the 1960s, but the following decade began with a kind of counter-revolution, as acoustic folk returned, and singer-songwriters such as James Taylor, Cat Stevens, Joni Mitchell and Carole King ascended to the top of the charts. The perennial outlier Todd Rundgren went his own way, from his ’60s British-Invasion-in-a-garage group Nazz, to the relative calm of two solo albums (which had critics comparing him to Laura Nyro) and the top 20 single “We Gotta Get You a Woman.” In early 1972 his ambitious double-LP Something/Anything arrived to substantial acclaim, to be followed by an against-the-grain, brilliant, often baffling psychedelic album, A Wizard, A True Star, on March 2, 1973. Some thought it was a masterpiece, others a slab of unintelligible self-indulgence. In the original liner notes, Rundgren explained he was “not a rock star, just a musical representative of certain human tendencies: the Quest for Knowledge and the Quest for Love.”

The use of hallucinogenic drugs had a profound effect on the music of the 1960s, but the following decade began with a kind of counter-revolution, as acoustic folk returned, and singer-songwriters such as James Taylor, Cat Stevens, Joni Mitchell and Carole King ascended to the top of the charts. The perennial outlier Todd Rundgren went his own way, from his ’60s British-Invasion-in-a-garage group Nazz, to the relative calm of two solo albums (which had critics comparing him to Laura Nyro) and the top 20 single “We Gotta Get You a Woman.” In early 1972 his ambitious double-LP Something/Anything arrived to substantial acclaim, to be followed by an against-the-grain, brilliant, often baffling psychedelic album, A Wizard, A True Star, on March 2, 1973. Some thought it was a masterpiece, others a slab of unintelligible self-indulgence. In the original liner notes, Rundgren explained he was “not a rock star, just a musical representative of certain human tendencies: the Quest for Knowledge and the Quest for Love.”

Always the spiritual and musical seeker, in 1971 Rundgren had embarked on a period of experimentation with hallucinogens, including mescaline, psilocybin and DMT. He listened to a lot of progressive rock by Frank Zappa and Mahavishnu Orchestra, and developed plans for an album in which songs would continually blend into each other, and even fragments and incomplete ideas could be included in the collage. Shifts in mood would be encouraged, and wildly divergent styles (Broadway show tunes, Philadelphia soul, heavy metal and nascent punk rock) all eventually made appearances. He later characterized his concept and working method as not only psychedelic but ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder).

To actualize his vision, Rundgren and keyboardist Moogy Klingman established a recording studio on 24th Street in Manhattan and dubbed it Secret Sound, working whenever they wanted to for several months, sometimes inviting drummer John Siomos, keyboardist Ralph Schuckett and bassist John Siegler and other guests to contribute ideas. Still, Rundgren played most of the instruments himself, and even served as his own engineer, running back and forth from the booth to the studio, a dexterity Klingman found astounding.

[Rundgren was finally inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, in their Class of 2021.]

A Wizard, A True Star, clocking in just under 56 minutes, was one of the longest single LPs ever issued, and it had to be specially mastered to prevent the needle from jumping out of the groove—listeners were advised to play it loud to get the full effect. The first side is a suite of 12 tracks titled “The International Feel (In 8)” and the flip is titled “A True Star,” containing seven cuts, one of which is a superb medley of four soul music standards: “I’m So Proud,” “Ooh Baby Baby,” “La La Means I Love You” and “Cool Jerk.” It was packaged in a specially cut sleeve that along the edges followed the surrealistic artwork by Arthur Wood. Rundgren seemed to be announcing that if other artists were square, he was a unique, previously unseen shape.

Side one begins with the anthemic, overloaded, somewhat disorienting “International Feel,” with multiple Rundgren vocals, booming drums, what sounds like a dozen swirling synthesizers inside an airplane that’s taking off, and a wailing guitar solo swamped with special effects.

Listen to “International Feel”

It eventually gives way to “Never Never Land” from the 1954 Broadway musical Peter Pan. Rundgren sings the wistful Adolph Green/Betty Comden lyrics straight, with multiple keyboards backing him, before the instrumental “Tic Tic Tic It Wears Off” acts as a bridge to the screaming, punk-metal “You Need Your Head” and “Rock and Roll P*ssy,” each about a minute long. If that’s not enough to challenge the listener, Rundgren then pushes out some crazy noise aptly titled “Dogfight Giggle” before laying into a near-perfect but brief pop tune called “You Don’t Have to Camp Around” and the Zappa-esque instrumental “Flamingo.”

Listen to “Flamingo”

If listeners haven’t bailed by this point, they are heading toward the suite’s longest tracks: “Zen Archer” is a gorgeous, multi-part pop song that shows off Rundgren’s impressive falsetto, dexterity with complex instrumental and vocal harmonies, and contains a passionate saxophone solo (from Michael Brecker) and “When the Sh*t Hits the Fan/Sunset Blvd,” a song with apocalyptic lyrics in a white-funk-meets-jazz setting. In between, Rundgren, perhaps taunting his audience, chants, “You want the obvious? You’ll get the obvious,” in the pastiche he calls “Just Another Onionhead/Dada Dali.” A reprise of “International Feel” ends the side. Whew!

Listen to “Just Another Onionhead/Dada Dali”

The second side is less challenging, focusing more on Rundgren’s pop and ballad songwriting chops (although it has its share of wild studio experiments and amazing instrumental breaks). It begins with the terrific love song “Sometimes I Don’t Know What to Feel” and concludes (after traveling through what Rundgren described as the “hole in your memory” represented by the sublime 10-minute R&B medley) with one of his greatest compositions, “Just One Victory” (the only track not recorded at Secret Sound).

Listen to “Just One Victory”

Summing up the depleted idealism of the ’60s, Rundgren argues for a renewed commitment, singing, “We’ve been so downhearted, we’ve been so forlorn/We get weak and we want to give in/But we still need each other if we want to win…we need just one victory and we’re on our way.” Even today, Rundgren plays it at nearly every show, and told biographer Paul Myers “people get pissed if we don’t do it.”

When Rundgren tours, tickets are available here and here. His extensive recording library is available here.

Watch Rundgren perform “International Feel” live in 1994

5 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThanks for writing this review. I agree: A wizard a true star is a landmark album. It explored many uncharted musical avenues, in an era where there were not as many options for sound sculpting as we have today. What I like most about is the radical mixing of styles. It is a true masterpiece.

He should be in the Rock and Roll of Fame

It’s doubtful this kind of record would fly today, and more’s the pity, as modern listeners don’t have the patience for a concept recording of sonic artistry. Folks today just want to download tracks, or pick out tracks, and that blows a masterpiece like this to smithereens, as it needs to be heard in a total listen.

One thing I will say about AWATS, is that I’ve always thought that the “special mastering” required to accommodate its unusual length always sounded thin and tinny. Now that the length is no longer an issue, I’d love to see Todd go back and re-master these recordings to give them the full breadth of sound they deserve.

Also, really doubting this record has anything to do with drugs. (That synopsis sounds like something that would come from my mom and dad back in the day.) It’s really about an awakening in Todd with relation to his comfort with both advancing studio techniques and new keyboard electronica abilities. The record is a bunch of songs and sketches illuminated by a new playground of sound possibilities.

It sounds like he recorded bits and pieces. Then he threw the tapes in the air. Then he he picked them blindfolded from the studio floor, so he doesn’t see which tape is which. Then he put them together again. Then he listen it and thinks this is crap but i put it out as an album anyway. Voila! Everyone says it’s a masterpiece! But not me. Don’t know how many times i have tried to listen it and everytime the conclusion is this is boring. Doesn’t this record never end?