When the 1980s arrived, Styx was well on their way down a path that would secure the band’s greatest successes and ultimately seal their fate. The signpost was 1979’s Cornerstone, which found the Chicago-grown five-piece migrating from the progressive rock territory of its early days to a pop-first sensibility epitomized by the album’s lead single and signature hit, the expansive ballad “Babe.” Undeniably popular as it would prove to be—in December 1979 it spent two weeks atop Billboard’s Hot 100, a position the band never reached before or again—it was even then a bit of a puzzler, a remarkably Main Street song for a band that previously had trafficked in such entertainingly crackpot musical bluster as “Come Sail Away.”

When the 1980s arrived, Styx was well on their way down a path that would secure the band’s greatest successes and ultimately seal their fate. The signpost was 1979’s Cornerstone, which found the Chicago-grown five-piece migrating from the progressive rock territory of its early days to a pop-first sensibility epitomized by the album’s lead single and signature hit, the expansive ballad “Babe.” Undeniably popular as it would prove to be—in December 1979 it spent two weeks atop Billboard’s Hot 100, a position the band never reached before or again—it was even then a bit of a puzzler, a remarkably Main Street song for a band that previously had trafficked in such entertainingly crackpot musical bluster as “Come Sail Away.”

When disagreements about a band’s direction make it all the way through the production process, it’s rare that things end well, and Styx was no exception. Like contemporary Police albums on which a listener could tell without looking at the liner notes whether a song was a Sting, Copeland or Summers composition, Styx delivered material that was neither consistent in approach nor particularly cohesive within its overall package, splitting between the decisively commercial offerings driven by keyboard player and vocalist Dennis DeYoung and the more nomadic rock content composed by guitarists Tommy Shaw and James “J.Y.” Young (both supporters of including “Babe” on Cornerstone, incidentally, though disagreements about what single should follow it almost led to Shaw’s exit and later DeYoung’s firing), and while the two camps may not have been in any kind of production standoff, differences regarding what exactly the band was at its core were audible on the finished product.

Styx in a 1981 publicity photo (from left): Chuck Panozzo, James Young, Tommy Shaw, Dennis DeYoung and John Panozzo

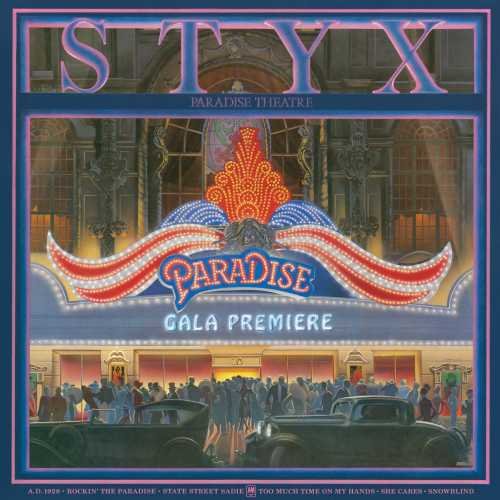

Those tensions remained in evidence on the group’s 10th album, Paradise Theatre. A set that could credibly be credited to Various Artists, it is a concept record thin on attachment to the concept that plays tug of war between commercial considerations and a different type of artistic ambition, and though it sometimes works, it ultimately proved a highly popular marker of a substantial step toward the group’s dissolution.

Ostensibly a story cycle about the failure of the American Dream to materialize in reality, told through the short lifespan of a Chicago theater, the set opens on “A.D. 1928” with a melody that threads further into the record. It’s a DeYoung tune through and through, following its plinking synth line straight to Broadway aspirations as he ladles the resonant snap of his vocal across its cool flow. There are traces of playful production in the tune’s vocoder-derived response vocals, but it is at its heart a pure pop concoction.

That curtain-lifter segues into the propulsive mélange of guitar and piano “Rockin’ the Paradise,” with DeYoung’s lead vocal a font of simple bravado and the occasional growl alongside a boisterous array of glissandos and hammered keys. John Panozzo’s drums flash from one channel to the other and the electric guitar fill has slickness to spare in a sprightly digestible rock rush that uses its arrangement to add its sonic sparks. The song would, at the end of the album’s run, become its fourth and final single, reaching as high as #8 on the mainstream rock standings, the ideal chart for its sensibility.

A peak six spots higher—even as it reached #9 on the all-comers Hot 100—was the outcome for the Shaw-powered “Too Much Time on My Hands.” Forging a springy spine around a synth pulse alongside drum hits that bounce around the mix, the tune sports a mildly quirky edge, but generally merges multiple sensibilities into smoothed-over accessibility. Shaw’s vocal sells the loser’s lament (both in the song and in the astonishingly literal accompanying video) with a spirited, insistent and amusing approach, which DeYoung’s sharper, more dramatic singing wouldn’t have carried to similar results. It would be the only Shaw-led top 10 single in the band’s entire catalog.

All of what would turn out to be the record’s singles were bunched on side one, among which the crisp, horn-dolloped “Nothing Ever Goes as Planned” came third. A DeYoung number, it’s a theatrical enterprise that revels in boisterous touches. Its guitar fills bring flavor without any particular sharpness in support of DeYoung’s bright yelp, yielding a so-so song with a bit of bounce. It would prove the record’s least successful single, peaking at #54.

The album’s lead radio offering also was its biggest hit. “The Best of Times” was a signpost of the band Styx had become, re-upping the melody established in “A.D. 1928” into a profoundly well-groomed chunk of pop-rock. Classically DeYoungian, it is showy and digestible, far closer to Broadway than any kind of art-rock in a power ballad of limited power. Piano-driven and loaded with gusty pop tropes, it was a major hit, reaching as high as #3 on the Billboard singles chart, but it’s telling that it climbed only as high as #16 on the mainstream rock chart. A pop song through and through, “The Best of Times” is polished, professional and sports a memorably spacious hook, but as a mark of the band’s approach did not point toward artistic evolution.

“Lonely People” opens the second side with more theatricality offered in a bid for atmosphere, segueing from sounds of a rainstorm and background conversations into a horn fanfare, which gives way to DeYoung’s vocal floating over electric guitar filigree buried in the deep background. He snarls his way across its deliberate churn, plugging into its rock-lined melodrama.

Shaw composed and leads “She Cares,” a marriage of a throwback-leaning doo-wop lilt to a slick, piano-trimmed rock bob. It qualifies as a display of variety, but only as a trifle, a light mundanity rather than Shaw pushing anything singular in the limited space he commands on the record.

A fairly straightforward anti-drug anthem, somehow “Snowblind” made its way into the crosshairs of the busybodies at the Parents Music Resource Center, who ludicrously accused the band of inserting backwards Satanic messages into the track. It’s a Young/Shaw driving rock affair, with Young singing the verses, effects edging his deliberate delivery, and Shaw adding urgency tonally to drive the somewhat punchier choruses. Fascinating as it is that a song about the dangers of cocaine became a source of derision among the massively morally judgmental, the number had a lasting effect no one could foresee at the time, in that the odd reaction it received helped inspire the storyline for the group’s next record, a set that would hasten the band’s demise.

In a curious bit of sequencing, Young’s largest contribution on the set immediately follows, with “Half-Penny, Two-Penny.” Different than a Shaw tune but still in its general vicinity, and wildly different from DeYoung’s output, it feels where it’s placed like a detour from a detour. An insistent curio with a spacey interlude that almost sounds like the band trying to get back to its prog bona fides, the tune is an inflated piece of theatrical rock, but staged in an entirely different theater than the one in which DeYoung is playing.

That track gives way to wrap-up as a technicality with “A.D. 1958,” bringing back the melody that opened the record and DeYoung’s role as narrator, even though it follows songs that feel neither climactic to any particular story nor elements of any particular whole. DeYoung is earnest in his attempt, but it lands as a perfunctory bookend trying to hold together a “concept” that is largely an aggregation of spare parts.

The set concludes with just under 30 seconds of additional flavor, drizzling player piano in the snippet “State Street Sadie.” Part of a larger composition that the band would offer in full (including its clarinet solo) during the credit roll that played on an onstage screen at the end of shows in support of the record, DeYoung would later note that if he had it to do over again he would have included it in full on the record.

Ultimately, that absence was irrelevant to the set’s achievement of its artistic vision. Taken separately, the album’s two sides place the band’s strengths and limitations at the time on vivid display. The first side is an attempt to build something with a structure and through line, all the while spinning hits that appeal to fans of both pop and rock, and it achieves that end spectacularly. The second side is more of a mishmash, and one on which the appeals are far more limited, and the attempt to thread it together at the end is a reminder of how difficult it is to make such disparate visions cohere.

When it reached stores January 19, 1981, Paradise Theatre did huge business on the strength of its hits, topping the charts in two runs that April and May, and moving more than four million copies in the years following its release. If not the band’s crowning artistic achievement, it was its greatest commercial success, coming even as cracks were starting to show. Two years later, Styx would return with the album that would seal its fate, as DeYoung’s reaction to the “Snowblind” backlash led him down a path to what would become Kilroy Was Here. That record, the signature number on which was the ham-handed “Mr. Roboto,” brought the band to a synthesizer-pop crossroads from which it never would recover, and would prove the final album to feature its classic five-man lineup.

Related: The #1 albums of 1981

Styx endured in one form or another, but the divide between the DeYoung and Shaw/Young camps would in the end prove to be the band’s undoing. The latter carry on the band’s name and continue to play its catalog—even as they are vocal in their disdain for the path DeYoung pushed them down to get to those hits. While its former frontman has suggested the band should reunite for one last tour of its core glory-days members, that seems unlikely, leaving fans who wish it were otherwise with memories time-worn and distant, a curious echo of the transformation from vibrant beginnings to a run-down ending of a once-grand theater pictured on the covers of the group’s most popular album.

Styx have a busy tour calendar. Tickets are available here and on StubHub. Their recordings are available here.

6 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationAnother cool thing about the LP, is that it was one of those “laser-etched” disks that had a short run as a flavor of the year. “True Colors” by Split Enz was another.

Say what you want . . . Paradise Theater and Kilroy Was Here rocked. They’re my favorite Styx LPs.

It seems like you and me have two different feelings on this album. I think this is a masterpiece, and this is not their best. One thing that made this band stand out, 3 vocalist, 3 different styles of music. Shaw and JY may both be rockers, but really they have different styles and takes on their music. DDY, while he maybe “labelled” the ballad guy, he still can rock or roll to whatever type of music is needed.

As soon as as Rock n Roll bands turn to power ballads and pop pop pop musik- being a smart arse here—it kills the band for me. Pieces of eight was much better than Paradise Theater in MHO. Aerosmith died out for me with all the love ballads-crazy, I want to miss a thing (haha), Angel etc. yuck. Give me: Toys in the attic, self-titled. They may sell lots of records with these teenie bopper tunes but no thanks—Styx was great in concert when they played the albums pieces of eight and The Grand Illusion. I saw the Paradise Theater tour as well—why? Our 16 year old GF’s !!

Styx did popularize that power ballad sludge that infected the 80s, didn’t they? Heart went down that path and that killed my buzz for them.

Now that I think about it, I think “You Need Love” might be my fave Styx track, from back in the old Wooden Nickel days.

‘Too much time on my hands’ was by far the best song they ever did, it rocked and you can’t say the same about much of their operatic stuff from DeYoung. They had some good stuff, I think if DeYoung had toned down the operatic schtick they could have kept on going.

Dennis is Styx.