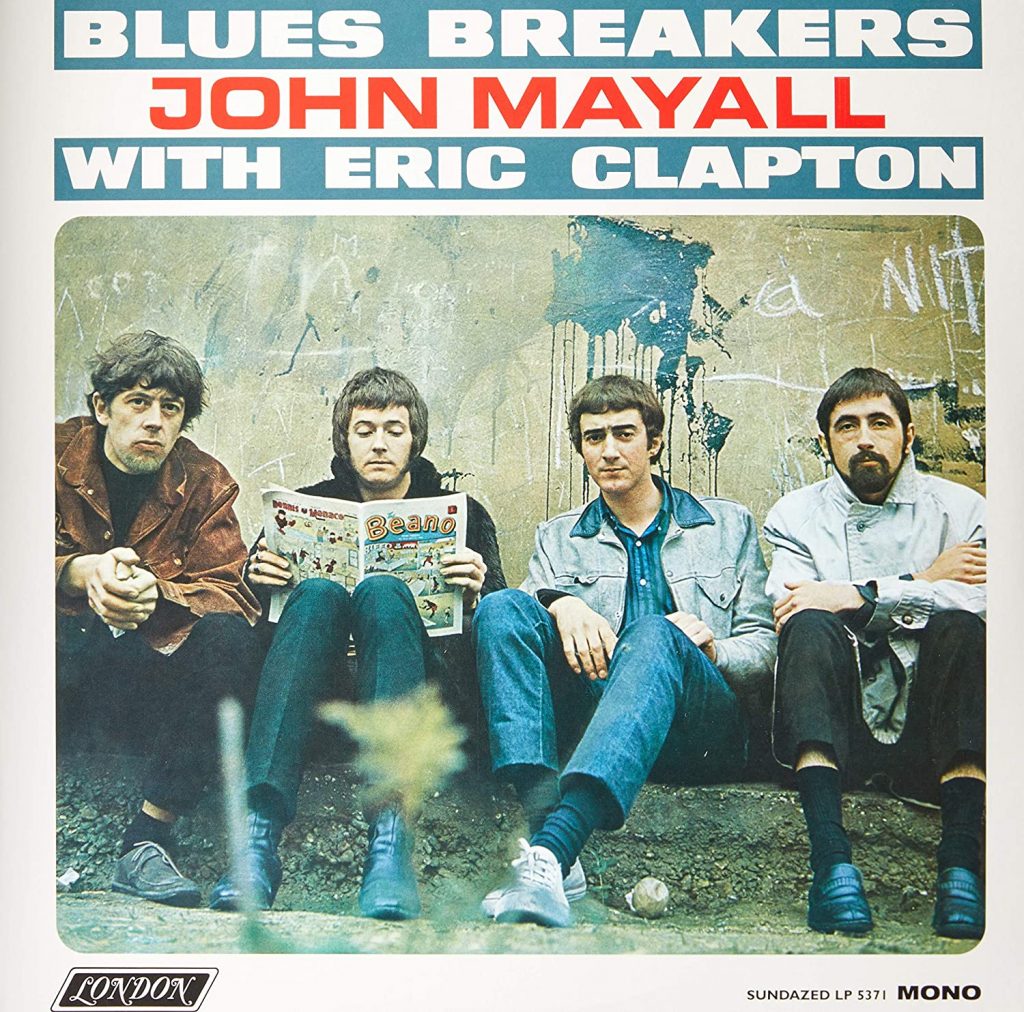

When John Mayall’s ‘Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton’ Broke Down Boundaries

by Lee Zimmerman Like many who were swept up in the tidal wave of blues and R&B that engulfed England in the early to mid-’60s, John Mayall took his inspiration from such forebears as Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, Robert Johnson and all the other artists that furthered seminal sounds spawned from the working fields of Mississippi, prior to a migration to the industrial environs of the Northeast. Mayall would go on to not only help introduce blues to Britain, but also to foster the careers of any number of aspiring musicians who would make a profound impact on the whole of the U.K.’s music scene in the decades that followed.

Like many who were swept up in the tidal wave of blues and R&B that engulfed England in the early to mid-’60s, John Mayall took his inspiration from such forebears as Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, Robert Johnson and all the other artists that furthered seminal sounds spawned from the working fields of Mississippi, prior to a migration to the industrial environs of the Northeast. Mayall would go on to not only help introduce blues to Britain, but also to foster the careers of any number of aspiring musicians who would make a profound impact on the whole of the U.K.’s music scene in the decades that followed.

Mayall’s outfit, the Blues Breakers, is best regarded as the band that shifted the tide and brought blues into the British mainstream. There were others who played a role—Cyril Davies, Alexis Korner and his band Blues Incorporated—but none played as direct a role in that critical crossover as the Blues Breakers. That became most apparent as a result of the group’s 1966 sophomore set, formally titled Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton. It’s notable that Clapton should share equal billing with Mayall at this point, given that he had only a brief tenure with the band following his departure from the Yardbirds. Nevertheless, he soon found himself on the cusp of singular stardom once “Clapton is God” graffiti began appearing on walls around London. Clapton himself never took that notion seriously, but his entry into the Blues Breakers clearly brought the band added attention, especially in light of the fact that the group’s debut, a live recording with the somewhat misleading title John Mayall Plays John Mayall and released the year before, was largely ignored.

Related: Our interview with John Mayall

Other than Clapton, who took the place of the departed guitarist Roger Dean at Mayall’s urging, the Blues Breakers lineup remained intact, with Mayall on vocals, keyboards and harmonica John McVie on bass and Hughie Flint on drums. In addition, a modest horn section was added in post-production and given prominent placement on the Mayall composition “Have You Heard.”

Notably, the album marks Clapton’s first turn as a singer in the spotlight, courtesy of his lead vocals on the Robert Johnson cover, “Ramblin’ on My Mind.”

“Eric was very much into Robert Johnson at that time,” Mayall recalls in the liner notes of a 2001 reissue. “I encouraged him to have a go, saying, ‘What have you got to lose?’ He was a little reticent about singing it, but I had no doubts whatsoever.”

Mayall became a father figure to Clapton, who had become disenfranchised from the Yardbirds when the group adopted a more distinct pop template after scoring a massive hit with “For Your Love.” Mayall subsequently indulged Clapton’s love of blues by introducing the young guitarist to the blues masters and offering him a prominent role within the band.

The wisdom of that decision became immediately apparent on the album’s opening track, the Otis Rush/Willie Dixon co-write “All Your Love.” Clapton’s stinging guitar kicks off the proceedings solidly, but once Mayall’s vocals take over, the song finds a firm foundation, which then takes a tear toward a fiery conclusion fueled by Clapton’s riffing and Mayall’s assertive singing. It’s obvious even at the outset that the Mayall-Clapton alliance would prove a formidable combination.

The two songs that immediately follow, the Freddie King instrumental “Hideaway” and Mayall’s original composition “Little Girl,” maintain the same tack, both being exceedingly upbeat and spotlighting the symmetry between Clapton’s scorching fretwork and a rhythm section that follows faithfully while keeping the pacing at full throttle.

After that, the tempo slackens with “Another Man,” a traditional field work song that pulls back so as to bask in the basics, while keeping Mayall’s distinctive harp work firmly at the fore. Likewise, the Mayall-Clapton composition “Double Crossing Time” opts for a slow blues and helps keep things on an even keel. As Mayall says in those same liner notes, it was originally intended as a B-side for an unreleased single and first recorded with Clapton’s soon-to-be Cream collaborator Jack Bruce on bass. “It was originally called ‘Double Crossing Mann,’ after Jack Bruce, who walked out on us to join Manfred Mann!,” he remarks somewhat ruefully.

Other highlights include a spirited read of the Ray Charles classic “What’d I Say,” featuring a frenzied drum solo from Flint, and the Mose Allison standard “Parchman Farm,” a song that was destined to become an integral part of the Mayall repertoire for years to come. The harp riffing prefigures Mayall’s signature solo on “Room to Move,” a standout track from The Turning Point, released four years later.

Credit is also due producer Mike Vernon, who not only helped secure the group’s label deal with Decca, but also gave a nod to Clapton’s pyrotechnics, which the guitarist shared with a full fury. So too, the Blues Breakers were, by that time, a well-seasoned ensemble, making it easy for them to simply stroll into Decca’s Studio 2 and let loose with a full frenzy. The tracks that made the album were easily assembled as well; they were simply songs that had been an integral part of the Blues Breakers’ set list for several months before.

Not surprisingly then, the album, released on July 22, 1966, achieved substantial success in the band’s home country, hitting the top 10 in the U.K. and retaining its hold on the charts for some 17 weeks in all. In the U.S., where it was released on the London label, the album didn’t chart, but it influenced countless young rock fans to pick up a guitar and learn a few blues licks.

Listen to “Steppin’ Out,” an instrumental highlight from the album

Ironically, Clapton departed prior to the end of its run, but not before the Blues Breakers helped establish a blues-rock template that would linger long after in the popular music firmament. It would eventually reach its crest with Cream, Fleetwood Mac, Savoy Brown, Ten Years After and the other auteurs that shared their love of archaic blues within a contemporary context. Still, credit the Blues Breakers as being there first.

The album, and other Mayall recordings, are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Mayall and Clapton reprise the album-opening “All Your Love” live in 2003

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationListening to John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers featuring Eric Clapton brings back great memories. I remember listening to that as a kid thinking this has got to be the greatest music In the world. Not realizing what a huge star Clapton would become. The blues has been a part of my life ever since. Fantastic music, great memories.

Brings back so many memories of great blues by Englishmen!

Mayall certainly introduced me to the blues. That was a great time to listen to music. Lots of great bands got their start.

Dont’t ever forget Little Girl, Mayall’s tour de force. The drums are fantastic.