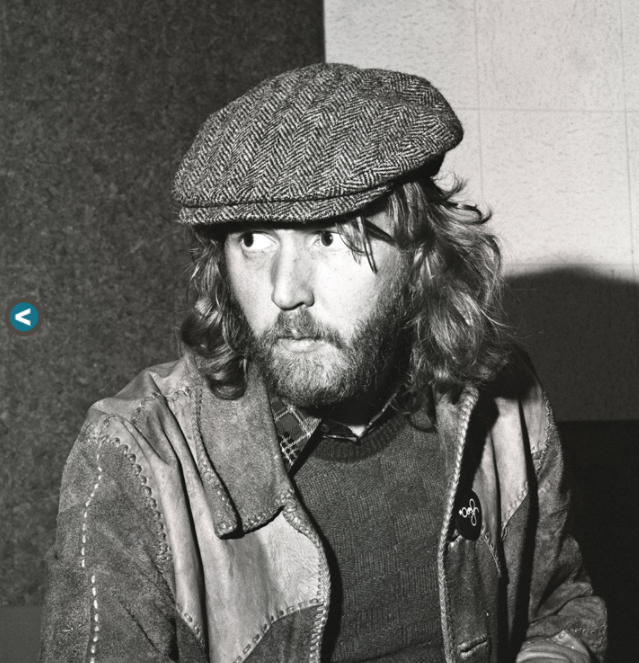

In 1971, Harry Nilsson was following his muse to curious places. After its tie to Midnight Cowboy made his cover of Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin’” a hit for Nilsson two years earlier, he headed in a variety of directions, releasing the quirky Harry the same year, and then self-producing an entire album of songs by the then-little-known Randy Newman. He oversaw the 1971 animated TV movie The Point!, for which he delivered an accompanying soundtrack. Unpredictability and the crystal clarity of his voice were Nilsson’s calling cards.

In 1971, Harry Nilsson was following his muse to curious places. After its tie to Midnight Cowboy made his cover of Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin’” a hit for Nilsson two years earlier, he headed in a variety of directions, releasing the quirky Harry the same year, and then self-producing an entire album of songs by the then-little-known Randy Newman. He oversaw the 1971 animated TV movie The Point!, for which he delivered an accompanying soundtrack. Unpredictability and the crystal clarity of his voice were Nilsson’s calling cards.

Always seeking something new, he parted ways with RCA producer Rick Jarrard and brought in Richard Perry for his next project. Perry, who had just delivered what would be a mini-comeback for Barbra Streisand in the form of her Stoney End album, had shown himself capable of shepherding artists ranging from Ella Fitzgerald to Tiny Tim, and was ideal for Nilsson at that moment: demanding yet innovative, he could unlock the best in a performer.

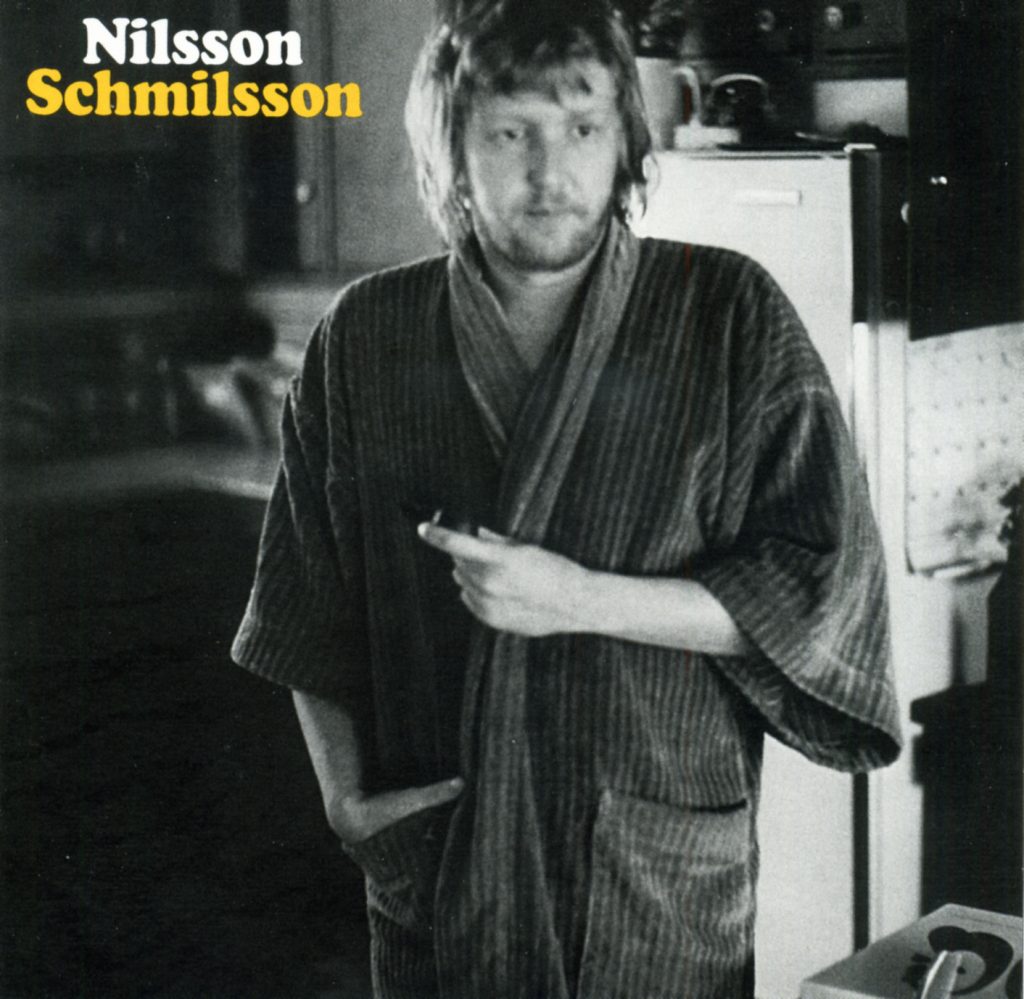

Work began on their first collaboration in Los Angeles, where Nilsson had previously recorded, while Nilsson was involved in The Point! Months later, on Perry’s advice they moved the production to Trident Studios in London, looking to achieve a different sound than they might create stateside. There they would develop Nilsson’s most successful album, the innovative and remarkably diverse Nilsson Schmilsson.

For the sessions, Nilsson and Perry employed a virtual who’s-who of top-shelf session musicians, including drummers Jim Gordon and Jim Keltner, Bobby Keys on saxophone, Gary Wright on piano, guitarist Chris Spedding, bassists Klaus Voorman and Herbie Flowers and several others.

The album’s first cut highlighted what the new partnership could yield. “Gotta Get Up” remade a song Nilsson had recorded three years earlier but never placed on an album. The London version retains the original’s fundamental springiness, but its friendly quality evaporates into an arrangement laden with sonic flavors, some of them heavy. Nilsson inhabits middle ground between speaking and singing, as his percussive piano is rounded out by plump horns and a ridging accordion, which nestle behind it like gathering clouds. Its flirtation with Beatlesque ’60s pop is catchy yet a little dark, and considerably more interesting in its final form.

Nilsson defied simple categorization, a playful music maker with loose boundaries. That quality would soon enough get him in trouble: his next record included several family-unfriendly moments, but it led to some extraordinary music. His cover of “Early in the Morning” is appropriate given that its originator Louis Jordan was a spiritual antecedent of Nilsson’s freewheeling attitude. With a light, ringing organ as its sparse backdrop, his chirping falsetto wrangle of the lyric, “Harry, you sure look beat” is amusing without turning farcical, using personality to drive the coolly rendered blues. Similarly character-driven, but with a bit more punch, is his rendition of “Let the Good Times Roll,” with a hearty, engaging performance draped over an old-school rhythm and blues vibe. Featuring Gary Wright on organ and Nilsson’s impromptu harmonica workout, its juicy bounce is inviting and personable.

Nilsson was an accomplished vocalist with excellent instincts, which makes “I’ll Never Leave You” a puzzle. Featuring many hallmarks of a conventional ballad, it is drizzled with sonic bits in a dreamy mesh of instrumentation (was that a harp?) and layered vocals, alloying easygoing elegance with some rather arch tuba punctuation. Nilsson’s singing is at times lovely amid the needy lyric, but it’s a notably one-sided performance, more earnest and plain in its unvarnished melancholy than anything else on the record. With its careful, haunting arrangement, there’s more going on than it might seem in a song that moves so slowly, but it’s a jewel with only one facet.

The album’s overarching looseness is driven by tunes that were mere sketches at the time recording began. Much of the vinyl’s first side was elaborated on the fly, which led to eccentric outcomes like the mildly off-kilter, folky rock of “Driving Along.” Just three songs away is the buoyant blues soul revue “Down,” and between them there’s “The Moonbeam Song,” a measured, softly hypnotic tone poem that balances between evocative and silly. Nothing sounds like anything else, promoting a singular dynamic in which the lone constant is Nilsson’s versatile presence.

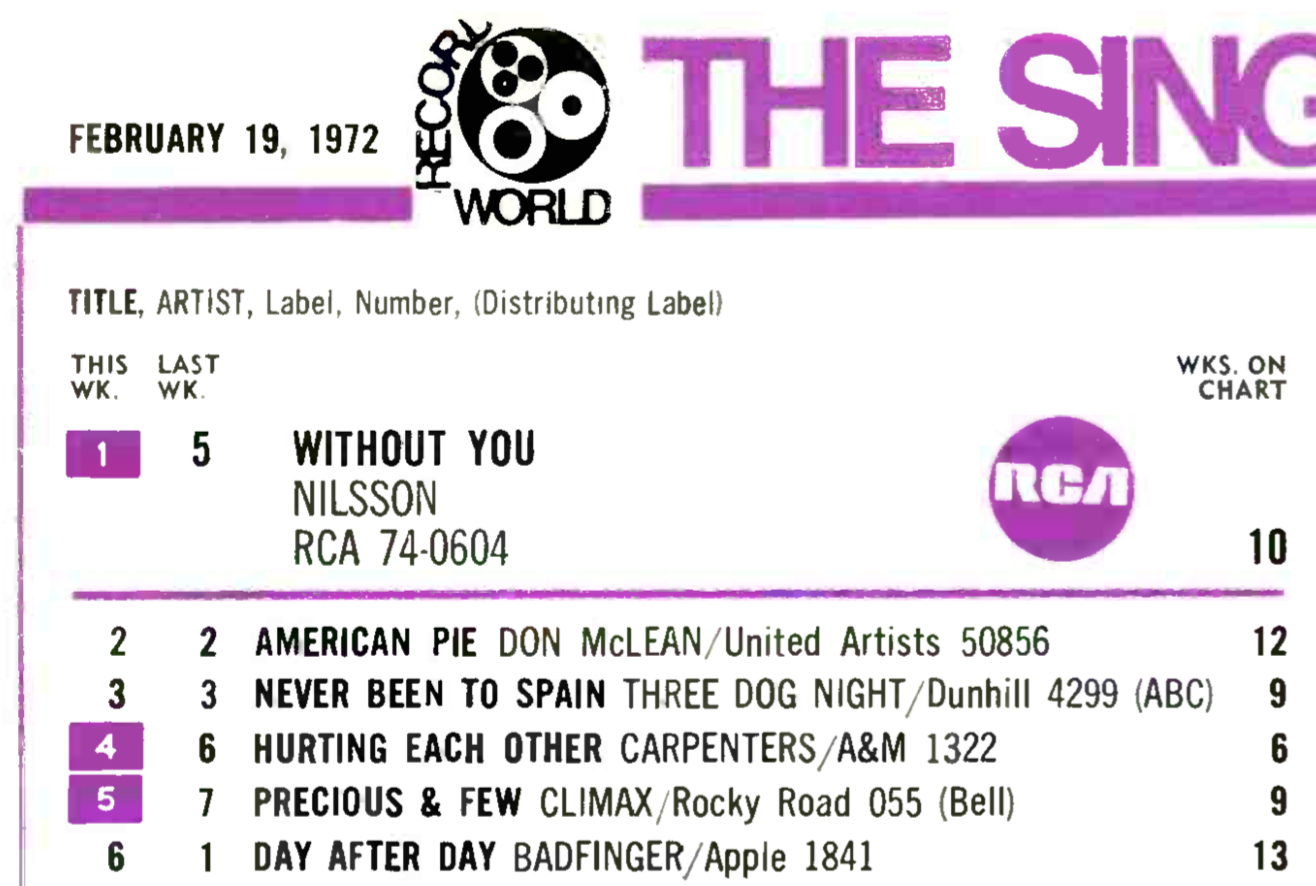

“Without You” topped the U.S. singles chart on Feb. 19, 1972

Side two sports three enduring songs wildly different from one another, and anything else. Among them is the million-selling cover of Badfinger’s “Without You,” which topped charts on both sides of the Atlantic. A pure showcase of pop balladry, its vocal is lustrous at all dramatic altitudes, atop a richly theatrical, symphonically tinged backdrop. The softly rendered singing with which the song begins is like a door opening, mesmerizing for its vulnerability and beauty. Paul Buckmaster’s strings make the same impact that they were delivering to any number of Elton John songs at the time, but the anchor of its appeals, and driver of its immortality, is Nilsson’s remarkable vocal.

Listen to Nilsson sing “Without You” from Nilsson Schmilsson

Related: The biggest U.S. radio hits of 1972

Iconic for different reasons is “Coconut.” Inhabiting multiple characters with appropriate accents amid its calypso pulse, Nilsson pursues amusement, and lands on something hypnotic. Fun, frivolous and experimental, it’s a clinic on effective production structure, thanks to an arrangement that feels airy even as it becomes denser, and vocals that ooze memorable personality. There’s a reason the line “put the lime in the coconut” has had decades of staying power—it is deeply catchy and smartly crafted. Typically referred to as a novelty song, “Coconut” is more inventive than gimmicky, and whatever else it may be, its charm is not an accident.

Watch the video for Nilsson’s inimitable “Coconut”

On an album of short, idiosyncratic songs, the seven-minute rock workout “Jump Into the Fire” is its own animal, a rare instance of Nilsson trading on straight-up rock grooves. He adds his own spin, particularly with an echo-draped lead vocal that pops right up to its wailing high end. Difficult as it may be to avoid mental images of a helicopter chasing Ray Liotta in Goodfellas while listening to the song these days (which, by the way, includes the great songwriter Jimmy Webb on piano), it is a lively slice of pop-rock craft, with signature touches such as a strikingly sludgy detuned bass rumble from Herbie Flowers, who would a year later achieve renown for what he brought to Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side.” Expansive and energetic as it changes direction throughout, it’s a moving target that’s frenetic and wild, yet ineffably magnetic.

Noteworthy for its scope and ambition, Nilsson Schmilsson—which was released in November 1971 and eventually climbed to #3 in Billboard, Nilsson’s highest-charting album by far— was justifiably rewarded with worldwide success that took him to the next level of stardom.

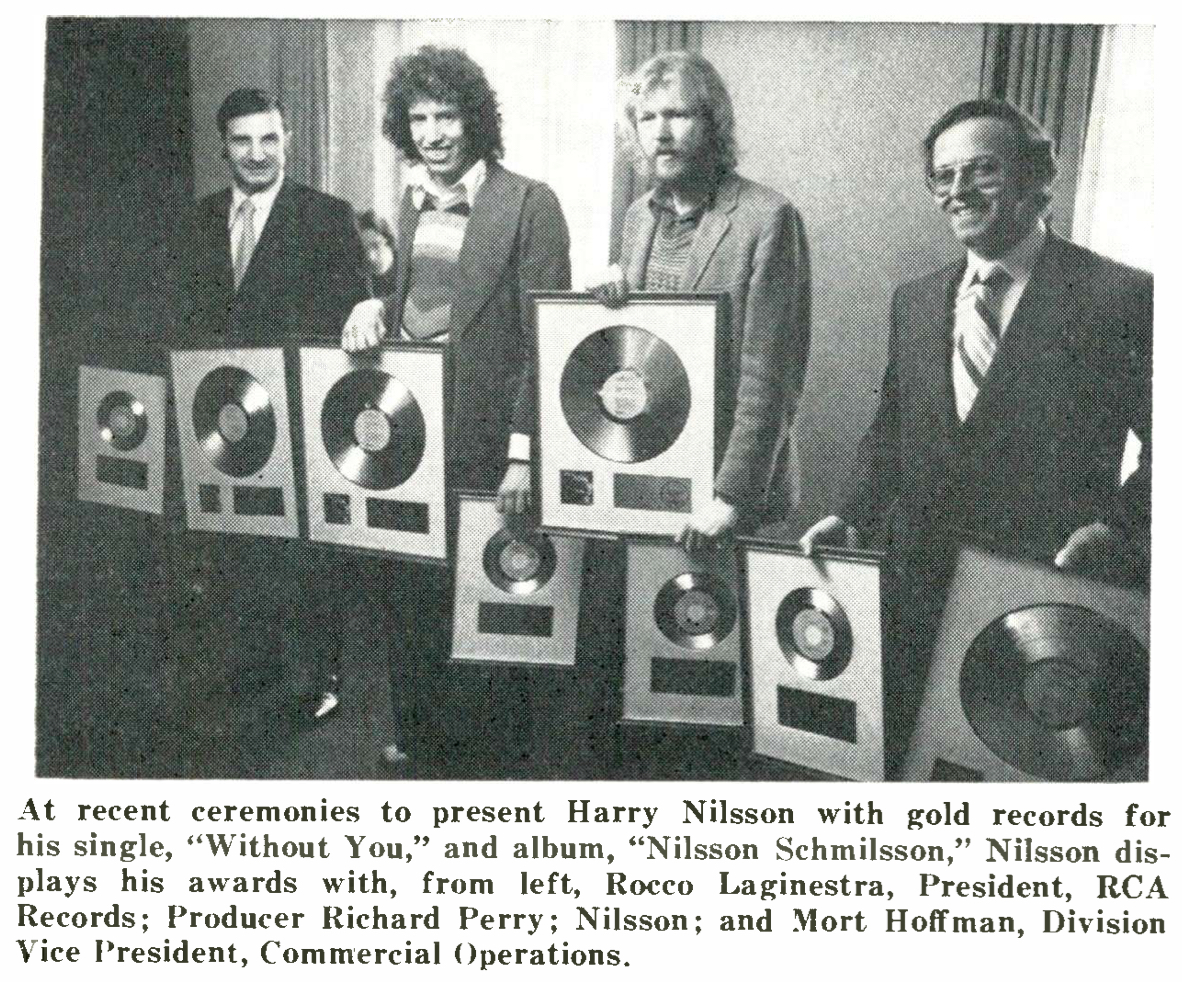

Nilsson and Richard Perry receiving Gold albums for “Without You” and Nilsson Schmilsson by the RCA brass, in March 1972

It would not last. By the time Nilsson followed it up a year later, nodding to its accomplishments with the title Son of Schmilsson, his relationship with Perry had deteriorated substantially, and its more vulgar lyrics exhibited a disregard for commercial considerations. Nilsson was always something of a drinker—it had been part of his process during the Trident sessions—but he soon became better known for his carousing with John Lennon than for new music.

Though frequently ambitious, his remaining 1970s output met with little success, and following Lennon’s death in 1980, he would record only sporadically until his death. In his wake, he was lamented as an artist who never achieved the audience he might have deserved, but given the priority he placed on an unwillingness to play to expectations, that was as much an endorsement as a lament.

Watch the classic helicopter chase scene from Goodfellas, featuring Nilsson’s “Jump Into the Fire”

Nilsson was born June 15, 1941. On January 15, 1994, he was struck down by a heart attack at the young age of 52. Nilsson Schmilsson and other of his recordings are available to order here.

5 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationA Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night was awesome.

Nilsson wouldn’t perform live or tour. He said he didn’t want to. I think his albums would have received a lot more credit than they did had he been more visible.

I’ve been a fan since “Harry.”

Richard Perry helped bring out the best in Harry. It’s unfortunate that couldn’t have continued, though as self-destructive as Harry became, I’m not sure it would’ve mattered much.

Totally agree Barry Mac. Read the chapter in Perry’s autobiography that deals with Nilsson. It is simultaneously heartbreaking and irritating to watch such an uncontrollable talent.

As many times as I’ve watched Goodfellas, I have to admit I’ve never caught that snippet of “Magic Bus” in the middle of “Jump Into the Fire”.