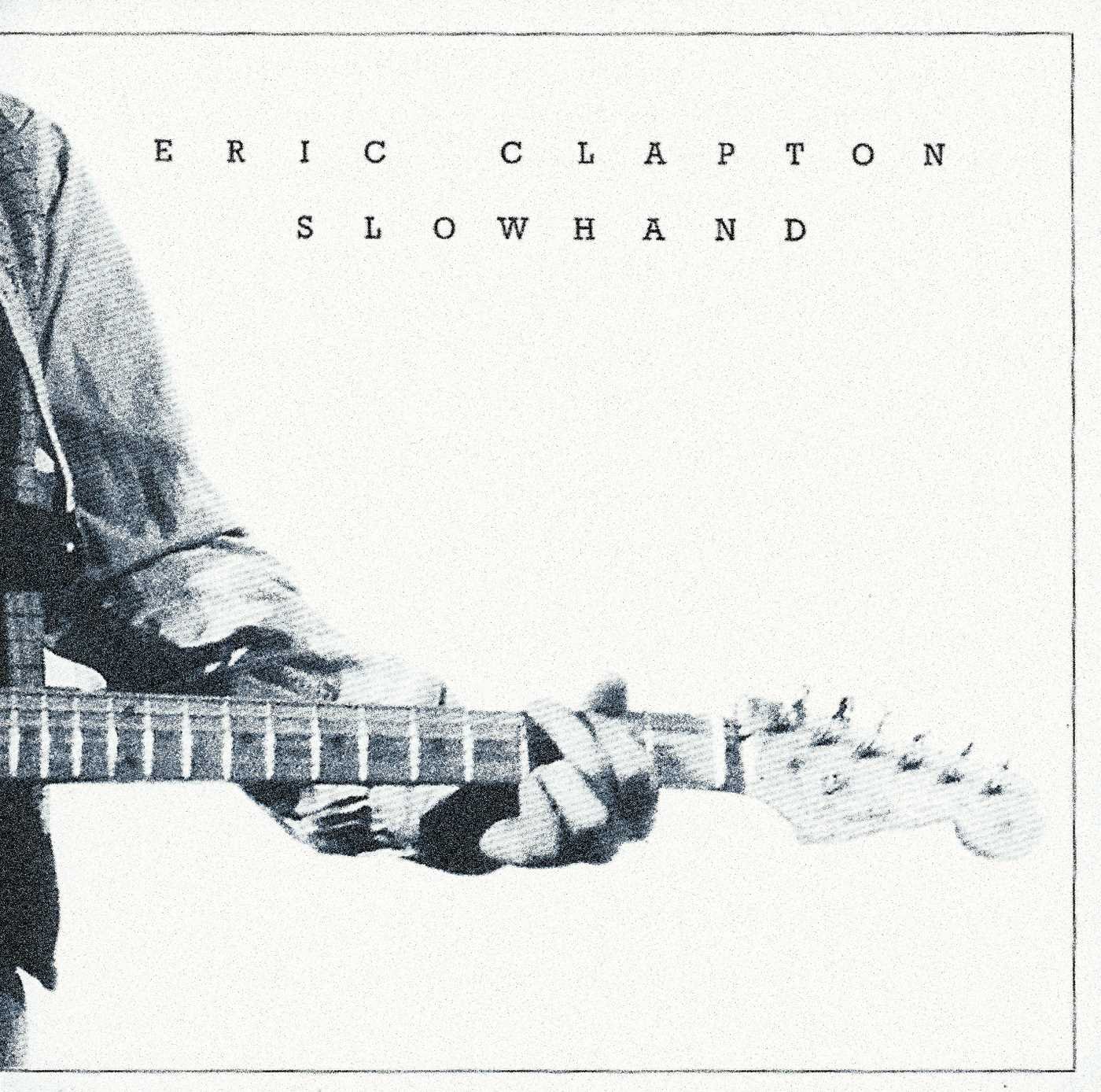

On his fifth solo studio album, Slowhand, Eric Clapton fine-tunes a template sketched persuasively three years earlier on 461 Ocean Boulevard: Rely on a tight band, buttress his own modest original songs with smart cover choices, and reach beyond his home base of electric blues to tap adjacent styles from pop to country to reggae.

On his fifth solo studio album, Slowhand, Eric Clapton fine-tunes a template sketched persuasively three years earlier on 461 Ocean Boulevard: Rely on a tight band, buttress his own modest original songs with smart cover choices, and reach beyond his home base of electric blues to tap adjacent styles from pop to country to reggae.

Like that album, 1977’s Slowhand offers a lucid balance of technical mastery and artistic modesty. The band, originally assembled for Ocean Boulevard’s Miami sessions, includes second guitarist George Terry, bassist and fellow Dominos alum Carl Radle, keyboard player Dick Sims, drummer Jamie Oldaker and backing vocalists Yvonne Elliman and Marcy Levy, a low-keyed lineup when compared to the A-list guests Clapton had featured on his previous long-player, No Reason To Cry. His deep admiration for The Band had led him to record that LP at their Malibu studio, where all five members of the quintet and their ex-boss, Bob Dylan, were invited aboard, along with at least a dozen more veteran players including Ron Wood, Georgie Fame, Billy Preston and Jesse Ed Davis, outnumbering and ultimately eclipsing Clapton’s own band and, to a degree, Clapton himself.

In the wake of that album’s mixed reception, Clapton enlisted producer Glyn Johns to restore focus on the front man, recording in London’s Olympic Studios. By then, Johns’ CV was impeccable, his early board work behind the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and subsequent production credits with The Who, the Eagles and Steve Miller confirming complementary skills as diplomat and cutting-edge engineer. Johns’ stated distaste for long jams also dovetailed with Clapton’s critical stance on mere grandstanding. While the artist and producer would allow for incendiary solos, a sense of editorial economy prevails on these tracks, as does a conscious effort to offset the album’s sharper rock edges with unabashed pop elements.

That compromise looms on the original LP’s first side, which leads off promisingly with Clapton’s take on J.J. Cale’s “Cocaine.” A tough-minded, medium tempo rocker, the song stalks its subject with coiled guitar figures and a strutting rhythm section punctuated by Jamie Oldaker’s ringing cymbal taps. That Clapton, now recovered from a heroin addiction while still battling lesser chemical demons to a draw, intended the song as a warning was explicit in interviews; that many fans missed its cautionary agenda and heard, instead, an ode to white powder was rooted in the drug culture of that era and the dangerous romance of life in the fast lane. As it was, Clapton may have left heroin behind but both he and Glyn Johns would recall the Slowhand sessions as well-lubricated by alcohol and softer drugs.

“Cocaine” reaffirmed Clapton’s undimmed power as a rocker, but the album’s next two tracks took a sharp right turn toward pop, especially on “Wonderful Tonight,” a languid valentine to Pattie Boyd, whom he had wooed away from her husband and his BFF, George Harrison. The song is a soft-focus hymn to romantic bliss framed by sighing guitar lines and crooned by Clapton in a voice far removed from the tormented howl unleashed seven years earlier on “Layla,” his desperate declaration of his feelings for Boyd while still married to Harrison. That fans of the latter epic might blanch at the laid-back reverie of “Wonderful Tonight” is hardly surprising.

Released as a single, “Wonderful Tonight” would see international success, peaking at 16 in the U.S., where it would ultimately achieve gold record status.

Slowhand wastes no time in clinching its mainstream appeal by following that radio-friendly ballad with an even more successful pop-rock hit, “Lay Down Sally,” co-written with Marcy Levy and George Terry, a breezy shuffle clearly influenced by J.J. Cale that revels in the two guitarists’ nimble picking and creamy backing vocals from Levy and Yvonne Elliman. (Cale’s “Tulsa Sound” amalgam of country, blues, rockabilly and jazz had already caught Clapton’s ear and invited his cover of Cale’s “After Midnight,” a highlight on 1970’s Eric Clapton.)

Watch “Lay Down Sally” performed at the Crossroads Festival in Madison Square Garden in 2013 with Vince Gill, Andy Fairweather Low and Doyle Bramhall Jr.

Where “Lay Down Sally” proves a slight but infectious charmer, Clapton follows a more oblique path on “Next Time You See Her,” a double-edged salute to an ex-lover addressed to a current beau that sheathes its underlying menace in a loping, country-fied arrangement. Lyrics signaling the singer’s continued affection (“Next time you see her, tell her that I care…”) give way to glimpses of unresolved passion and lethal jealousy (“If you see her again, I will surely kill you…”) in a darker variation on Clapton’s recurring preoccupation with star-crossed affairs of the heart.

That track may boast Clapton’s subtlest lyrics on the set. Less coherent lyrically but more musically powerful is “The Core,” a galloping eight-minute rocker that stands as a mission statement of sorts, reeling off inner conflicts between love and hate, fever and fury, anger and worry in a lyrical stream of consciousness. Far more eloquent are Clapton’s and Terry’s guitars, bobbing and weaving against each other, Sims’ lean organ figures, and the interlocking syncopations in Oldaker’s crisp drumming and Radle’s in-the-pocket bass lines.

In the aftermath of “The Core,” Clapton’s gently lilting cover of the late John Martyn’s “May You Never” offers a soothing balm in a hymn to friendship that feels like a benediction. Elsewhere on the set, Clapton draws from mellow country crooner Don Williams for “We’re All the Way” and Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup for “Mean Old Frisco,” sustaining the guitar hero’s career-long reverence for the blues, even as his overall design suggests a more mainstream pop sensibility. Such moderation succeeded in making Slowhand, released in mid-November 1977 [other sources say it was Nov. 25], his best-selling studio album to date, earning triple platinum status and an album chart peak of #2 in the U.S.

For an artist who famously fled the Yardbirds in 1965 when their breakout single hit, “For Your Love,” veered too far into pop for his taste, Eric Clapton’s solo outings would continue to synthesize other styles through and around the blues, particularly in his sleek late ’80s collaborations with Phil Collins. Clapton would eventually rekindle a more dominant blues style in the ’90s, partly in a retrospective mood rewarded on his MTV Unplugged sessions and album, partly through personal tragedy with the accidental death of his four-year old son, Conor, in 1991.

Whatever the motives, the self-proclaimed “journeyman” (as he titled his final ’80s studio full-length) would explore more personal collaborations with B.B. King and J.J. Cale, devote entire studio sets to purer blues (1994’s From the Cradle and 2004’s twin Robert Johnson homage albums) and launch his recurring Crossroads Festival guitar summits.

Clapton’s extensive catalog is available in the U.S./worldwide here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Clapton perform “Cocaine” at the Royal Albert Hall in 2015

Clapton has announced many concerts. Tickets are available here and here.

5 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationLike a legion of guitarists who grew up and came of age in the late sixties and early seventies, a period that birthed some of the greatest music, and greatest guitarists of all time, I was, essentially, mentored by Clapton, through his various early stages of bands and musical styles. His famous moniker “Slowhand” while maybe initially meant as an homage to a player who was considered the pinnacle of the instrument, hence “Clapton is god,” but, in reality, was a misnomer, because, even though Clapton certainly had the ability to shred, as he did on Cream’s version of “Crossroads,” speed was never what Clapton was really about. Rather, from a guitar player’s perspective, it was Clapton’s unique articulation of notes sounds, and styles that made him great. For one thing, he didn’t reside inside the familiar blues “boxes” on the neck, that so many players started out in, and which many, even famous ones, never really left. Jimi Hendrix was the same way, which is why his solos have such a distinctive sound, and go places that ordinary guitar players, and their neck hand muscle memories don’t naturally gravitate to. Contrary to shredding, for the most part, Clapton master of using space with notes that were purposely chosen, making his solos and sound immediately recognizable. But the Clapton I describe here, essentially disappeared, sadly never to be heard from again after making “Layla.” From a guitar playing point of view, all his major recording successes, and fan idolization in my view, from that point on were based on his legend, rather than the sounds that were coming out of his instruments. When Clapton first eschewed Gibson guitars, for Fender Stratocasters on his first solo album, and then “Layla,” it was delightful, as it came across as another adventure in the unique sounds that instrument could offer. But truth be told, the Stratocaster is perhaps the most difficult guitar to get “great” sounds out of, and there’s really been only a relatively select few of the many guitarists who’ve used them that have been able to make them sound more than one dimensional. Clapton is not one of those relative few, and really never has been. Aside from the wonderful guitar work he did on “Layla,” and to a lesser extent on his first solo album, in my opinion, the Stratocaster had a huge hand in neutralizing Clapton’s formerly incredible dynamics, intonations, and, most importantly, the one-of-a-kind articulations that made him a guitar legend in the first place. Over the years since, in his recordings, and in his live performances, Clapton has become a guitar noodler, with seemingly no plan or directed conversation in his playing. For essential early fans, like myself, every attempt I make to listen to his subsequent recordings, or watch his videos ends in frustration, sadness, and a bit of heartbreak at what we lost.

Sure he got older, but there’s something that went missing in the man. In so many of his live shows, he can’t even re-create or capture some of the dynamic intros to some of his solos, never mind the dynamics of the solos themselves. He’s like a really vanilla level tribute band of himself — unable to see or perceive what was actually great about what he once did. I can’t celebrate “Slowhand,” for things like “Cocaine,” “Wonderful Tonight,” or the abysmal “Lay Down Sally,” for as much as so many people might love these songs, they belong to the burned-out shell of a musician who could once be likened to musical greats like Coltrane and Miles Davis. It’s embarrassing to see him on stage with people like Jeff Beck, who continued to progress on his instrument his whole life and career. Clapton’s only redeeming achievement, in my view, aside from bringing the world his Crossroads’s Festivals, has been using these events to bring attention to our truly great younger guitar players, songwriters and vocalists like Doyle Bramhall II, Jonny Lang, and Jon Mayer.

Great observations. I especially agree with the Gibson/Fender comparison.

I was convinced of this after attending the NBTB tour. Clapton’s tone, phrasing, and all-around energy was so much more apparent when playing the Gibsons. I’ve followed Clapton’s career for quite a while and have also been disappointed in his recent (10-15 year) live shows. He has introduced me to many fine musicians with who he has shared the stage. I prefered when these artists were opening for Clapton instead of becoming a ‘band member’.

Good grief, consider the world without him.

Wanted to say “damn thats a bit harsh”, but the more I think about it, the more I agree

Although I own the majority of LPs from Clapton’s group projects (Cream, Derek and The Dominoes, Blind Faith) as well as solo studio and live releases, and admittedly enjoy them, I would agree with the references the author asserts to some of Clapton’s more pop-oriented work.

I personally would put Rory Gallagher and/or Roy Buchanan (amongst others) ahead of Eric Clapton any day, as a Blues-Rock artist, based upon authenticity, versatility, and live dynamics/performances (where all pretensions and flaws show up).

Also, Jeff Beck ahead as well, in the category of an experimenter and innovator.

Examples (and there are many to cull from), but I will limit to one Live release each, for the aforementioned reasons:

Rory Gallagher: Irish Tour ’74

Roy Buchanan: Livestock

Jeff Beck: Live at Ronnie Scott’s

Support Live Music.