Elliott Landy in his Woodstock, NY studio, May 2021 (Photo © Greg Brodsky)

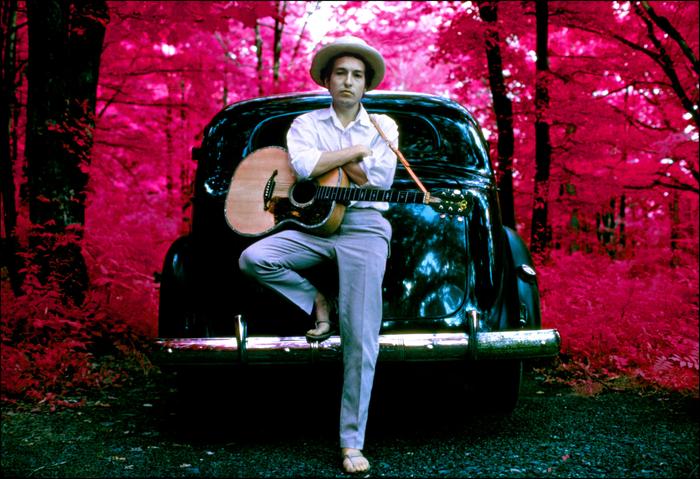

One of the most striking images of Bob Dylan—who celebrates his 82nd birthday on May 24, 2023—was only seen by a handful of people until decades later. It’s the now-famous “Infrared” photo taken by renowned music photographer Elliott Landy at Dylan’s home in Woodstock, New York, in the summer of 1968, when the artist was taking time off, at age 27, just to be with his family.

Shortly after the release of his acclaimed 1966 double album, Blonde on Blonde (“Rainy Day Women #12 & 35,” “I Want You,” “Just Like a Woman”), Dylan crashed his motorcycle in Woodstock. It would be more than a year later before he returned to the recording studio. And after releasing the John Wesley Harding album at the end of ’67, he spent another lengthy period at home.

In the summer of 1968, Landy, himself just 26, got a call from an acquaintance, the music journalist Al Aronowitz, who had been assigned a story on the musician for the Saturday Evening Post. “He calls me and says that Bob has agreed to have his picture on the cover,” recalls Landy. “I had only met Bob once at [his manager] Albert Grossman’s house in Woodstock, but he knew my work.”

At the time, Landy had been photographing such top rock acts as Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and the Doors, mainly at the Fillmore East in New York City. That led to his being asked to shoot The Band, including their debut LP, Music From Big Pink, which had been released that summer.

The photographer was living in New York City. “So I rented a Volkswagen bug and drove up to Woodstock. Al meets me in the middle of town and says, ‘Follow me.’ We drive through country roads lined with trees, and he turns right up a hill.” That zigzag lane was Upper Byrdcliffe Road, where Dylan lived with his wife and young children.

“Al stops his car and jumps out and signals me to wait,” Landy says. Aronowitz went inside the house and five minutes later he came out with Dylan behind him. “Elliott, this is Bob. Bob this is Elliott.’ He gets back in his car and speeds off, leaving me ten feet away from the most important musician in the world!”

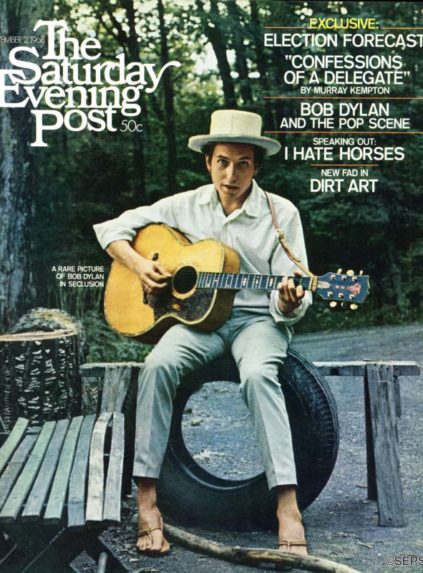

Elliott Landy’s photo of Bob Dylan on the cover of the Nov. 2, 1968 issue of the Saturday Evening Post

As they walked on the driveway, Dylan held a guitar. “Bob sat down on this tire and just started playing,” Landy recounts as we talked from inside his studio at his Woodstock home of several decades. “I see it now but I didn’t see it then: What other people wouldn’t do to be here, to experience this? But to me, it feels normal. I observed that it was special but inside me it felt normal. I was focused on taking the picture and not anything about the surrounding details of existence. I didn’t think about them at all. I was taking a picture of this person who was right in front of me.

“And that’s why we got on. I was dealing with his being, not his legend or what he had done culturally.

“I don’t tell people what to do when I photograph them. So he just picked up and walked over here and walked over there. It was very casual. When I do a shoot, my mind is totally focused on getting the composition and waiting for the right moment. It’s important for me to make the person look good and that’s why I’m there.

“He said how much he liked my pictures of The Band. Knowing what a great visual artist he is… he’s such a great painter… that’s really a compliment.

“I don’t like to intrude on people. It’s the circle of energy you create when you’re interacting with someone. And where you happen to be. And I let all of that kind of handle itself. The circular movement of life and I just get taken along. All my photos are like that. Just go with the flow. One of the most important life lessons is to go with the flow.”

Dylan sat down on the back of his truck.

Landy’s famous Infrared photo of Dylan was one of just two with that film that he snapped that day. “I had been introduced to Infrared film in 1967 when I was in Denmark,” he recalls. “I met a German photographer and he showed me this page of color slides that he did ‘just for fun.’ A year later I got some and was playing around with it all the time.”

As he writes in his Woodstock Vision book, “Kodak Infrared film is sensitive to both visible and infrared light. Using a yellow filter, the green trees of summer were transformed into red, giving the photograph a surrealistic look and feel.”

It was the first Infrared session that Landy did. “I was trying it out, experimentally. I took two shots and one of them came out as this great photograph. At least people say it’s great.” (laughs). As Landy notes in his book, “At the time, neither Bob nor I realized how special it was.” The photo first appeared roughly 20 years later when Spin magazine ran it as an insert in conjunction with a Dylan cover story.

He’s asked what reaction it made.

“Nothing great. I didn’t hear from anybody about it.”

At the time, there was no collecting of rock and roll prints. It’s since become a top five most-requested photo of his.

“When I started selling fine art prints, I thought people would want the ones they had never seen before. But people wanted the pictures they were familiar with.”

[To purchase a print of “Bob Dylan Infrared” or any Dylan fine art pigment print hand signed by Elliott Landy, click here and select the size. Then click “Add to cart.”]

There’s a unique coincidence between the photographer and his famous subject. As he told an interviewer, “Curiously, because our names are anagrams of each other – D-Y-L-A-N/L-A-N-D-Y – many people thought I didn’t exist… that I was Dylan under an alias!” There’s more: Landy’s wife Linda’s name at birth was spelled L-Y-N-D-A.

Related: Landy talked to us about his cover photo for Dylan’s Nashville Skyline album

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.