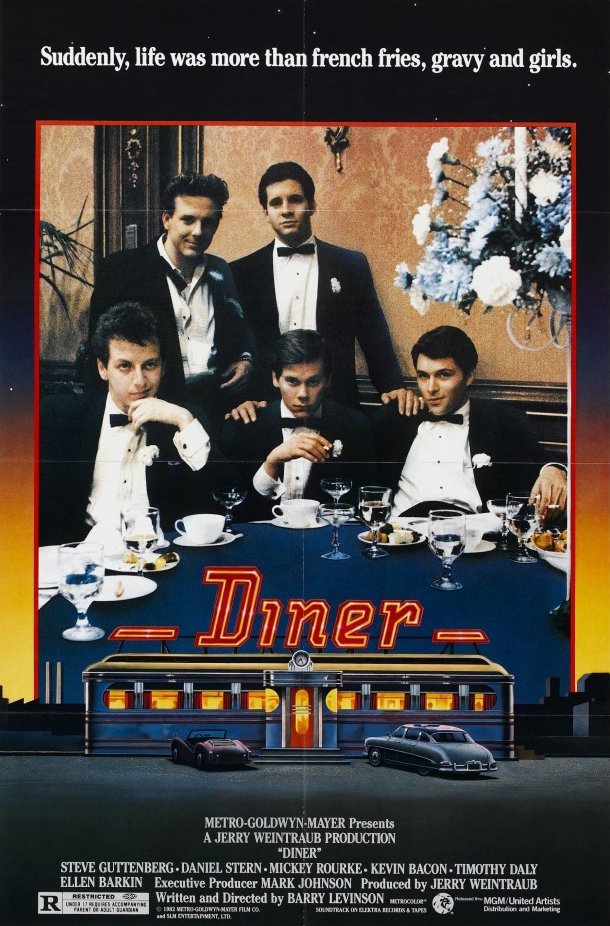

Music is central to the storytelling in Barry Levinson’s 1982 film Diner. We first learn of its importance early in the film when a couple of the young men who comprise the film’s core cast are discussing the merits of two of the day’s hottest vocalists, Johnny Mathis and Frank Sinatra.

Music is central to the storytelling in Barry Levinson’s 1982 film Diner. We first learn of its importance early in the film when a couple of the young men who comprise the film’s core cast are discussing the merits of two of the day’s hottest vocalists, Johnny Mathis and Frank Sinatra.

“You can’t compare Mathis and Sinatra,” argues Eddie, played by Steve Guttenberg. “There’s no way.”

“Eddie, they’re both great singers,” retorts Daniel Stern’s Shrevie, a cigarette idling in his hand as they sit at a table in Fells Point Diner, their favorite hangout.

“Sinatra’s a good singer but he’s too thin. I don’t like that,” continues Paul Reiser’s Modell, scrunching his face.

The boys volley some more and Eddie zeroes in on what matters the most. He looks over to his friends. “When you want to make out, who do you make out to, Sinatra or Mathis?”

“That’s a stupid question,” Shrevie replies. “It’s irrelevant. I won’t answer.” He waits a few beats, then elucidates: “I’m married. We don’t make out.”

Watch: Sinatra or Mathis?

(Never mind what happens when a third fellow, Boogie, played by a young Mickey Rourke, injects his own opinion. Watch the video right below to find out. His reply arrives about halfway.)

Diner, both written and directed by Levinson (his first directorial role, actually), is set in Baltimore in the very last days of 1959. The ’60s, with all of the seismic changes that decade will bring, are pounding on the door. A near-perfect coming-of-age tale, Diner follows the day-to-day doldrums and shenanigans, the aspirations and apprehensions, of six twentysomething guys, for whom adulthood and the maturity that comes with it are still just beyond reach. Until further notice, a plate of French fries with gravy makes for the ideal meal, and sex is something grabbed on the run or on the sly.

Practical jokes, foolish stunts and playful sparring are intertwined with the boys’ mostly monotonous daily activities. (Two words for those who’ve seen it: popcorn bucket.)

Some of them are more distressed than the others. Boogie, an out-of-control gambler, owes a ton of money to a wiseguy, who wants it now. Tim Fenwick (Kevin Bacon, in an early role) is a drunk screwup of no small proportions—he’s busy breaking windows with his bare hands when we first meet him.

The March 5, 1982, release—which also stars Tim Daly as Billy, in his theatrical film debut—has been called, by some, a prototype for Seinfeld. As with that TV landmark, not much of significance ever really happens in Diner, plot-wise, but as a character study it’s nuanced and revealing: Scene for scene, the film is a stunning portrait of a time in America when, on the surface, all seemed innocent and carefree but, of course, it is not: bubbling just underneath, trouble and tension.

All of this low-key bustle takes place to a carefully curated soundtrack featuring a wide cross-section of music from the era, from the rock ’n’ roll of Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry to the blues of Jimmy Reed and Howlin’ Wolf to the sweet generic pop that still dominated the radio.

Related: Another great diner scene, this one in Five Easy Pieces

Some of the friends have obsessions that, as much as anything, define their personalities. For Eddie, it’s football. Engaged to marry a girl named Elyse, whose face we never see, he won’t agree to make it official unless she can pass a difficult football trivia quiz.

But no feature story on Diner is complete without discussing the record scene. For Shrevie, the obsession is his music collection. Shrevie cares about his vinyl more than he cares about most anything else. For his wife, Beth, played to perfection by Ellen Barkin in her first major role, Shrevie’s obsession is beyond comprehension. Their missed cues on each other’s feelings lead to one of the film’s classic scenes.

As it begins, the camera is already closed in on a 12-inch album spinning on a period turntable. The light blue label appears to be ’50s-era Capitol. The slow piano blues that we hear is “Havin’ Fun,” by the singer and pianist Memphis Slim. (We are obligated, as record geeks ourselves, to point out that “Havin’ Fun” by Memphis Slim actually appeared on the Premium label—he did not record for Capitol.)

We see Beth’s arm next. She is returning vinyl album jackets to a shelf. Then she does her nails.

Shrevie calls her. “Beth, come here.”

“I’m doing a crossword puzzle,” she tells him. He grows more insistent. “Come here!”

Shrevie gives her a look of disapproval as she enters the room. “Have you been playing my records?”

“Yeah, so?”

“So, didn’t I tell you the procedure?”

“Yeah, you told me all about it, Shrevie,” Beth says. “They’re in alphabetical order.”

“And what else?”

“They have to be filed alphabetically and according to year.”

She’s not quite there yet. “And what else?” Shrevie asks her, his gaze still loaded with daggers. “What else?!”

“I don’t know.”

The automatic tone arm lifts off of the album. “You don’t know,” Shrevie continues. “Well, let me give you a hint, OK? I found my James Brown records filed under the J’s instead of the B’s. I don’t know who taught you to alphabetize, but to top it off he’s in the rock ’n’ roll section instead of the R&B section. How can you do that?”

Beth looks like she’d rather be anywhere else. “It’s too complicated, Shrevie. Every time I pull out a record there’s this whole procedure I have to go through. I just want to hear the music, that’s all.”

The look on Shrevie’s face says it all: She will never understand. To him it’s not about just hearing the music. It’s a door that opens into his lifestyle. To know these records, everything about these records, is the mark of a better human being. Beth is about to lose her status as a living, breathing person.

“You’re not gonna put Charlie Parker in with the rock ’n’ roll, are you?” Shrevie asks with incredulity. We know what’s coming next, even before he does.

Beth: “I don’t know.” She pauses. “Who’s Charlie Parker?”

The sparks shooting from Shrevie’s brain are enough to power a Cape Canaveral rocket. “Jazz! Jazz! He was the greatest jazz saxophone player that…”

“What are you getting so crazy about?” Beth interrupts. “It’s just music.”

But it isn’t. We know that even if she doesn’t.

Shrevie: “Don’t you understand? This is important to me.” He goes to his pile of 45 RPM singles. (It’s important to us to note here that the big shot record collector does not keep his 45s in protective paper sleeves, allowing them to get scratched.) Shrevie asks his wife to pick any record from the stack. She chooses a yellow and white one. “What’s the hit side?” her husband asks.

“‘Good Golly, Miss Molly,’” Beth says, fortunately getting it right.

Shrevie commands her: “Just ask me what’s on the flip side.” Of course, he nails it: “‘Hey! Hey! Hey! Hey!’ 1958. Specialty Records. See, you never ask me things like that. You never ask me, ‘What’s on the flip side?’”

“Because I don’t give a sh*t!” Beth says, finally reaching her boiling point. “Who cares what’s on the flip side of a record?”

“I do! Every one of my records means something! The label, the producer, the year it was made. Who was copying whose styles, who was expanding on that? Don’t you understand? They take me back to certain points in my life. Just don’t touch my records!”

Watch the Diner movie record scene with Shrevie and Beth

[Barkin was born April 16, 1954. She is still active and starred in the 2016-22 TV drama Animal Kingdom.]

But Beth still doesn’t understand. She never will. Shrevie might remember the song that was playing the very first time he laid eyes on Beth—it was 1955 and it was “Ain’t That a Shame,” presumably the Fats Domino version and not Pat Boone’s whitewashed cover—but that moment will always be frozen in time. What they had once will likely go the way of French fries and gravy as the ensuing years unfold—JFK will arrive and depart, there’ll be a space race and then there won’t be, the Vietnam War will take its toll and then it’ll end. Hiding in a closet to watch your friends in the act will give way to mortgages and car payments, kids’ braces and assisted living facilities.

Related: One more diner scene, this time from the final episode of The Sopranos

The guys’ paths will diverge; the Fells Point Diner will cease to see their like. Eventually, the diner itself will be knocked down, replaced by luxury condos. The Beatles will come along and break up, and Hendrix will live and die and disco, MTV and Madonna will all shine for a moment. Kids will be born into this world without ever knowing what a diner was.

Shrevie may or may not still be paying attention by the time CDs replace vinyl, and he’ll almost certainly be too old to care about downloads or Spotify or vinyl’s comeback. Will he even still have his prized collection? He’ll be in his 30s when Woodstock attracts half a million people younger than he. You can bet a vintage Presley on Sun that Shrevie won’t be in that crowd.

Watch a great scene toward the end of the film: Tim Daly’s Billy shows ’em how to rock

Daniel Stern was born August 28, 1957. Diner is available to stream or purchase here.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationWhen I went with a friend to see “Diner” in 1982, he asked what it was about, and I responded “something like ‘American Graffiti.'” Later, during the above record collection scene with Daniel Stern, knowing what a collector I was myself, he glanced at me, and I noted “Hey, the guy knows what he’s talking about.”

One of my favorite movies ever, and one of the very best scenes