In 1974, after two underperforming albums and five frustrating years trying to maintain a stable lineup in their band Supertramp, the English musicians Rick Davies and Roger Hodgson might have recalled an encouraging saying from their youths, which British schoolmasters often attributed to Winston Churchill: “Success is stumbling from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.”

In 1974, after two underperforming albums and five frustrating years trying to maintain a stable lineup in their band Supertramp, the English musicians Rick Davies and Roger Hodgson might have recalled an encouraging saying from their youths, which British schoolmasters often attributed to Winston Churchill: “Success is stumbling from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.”

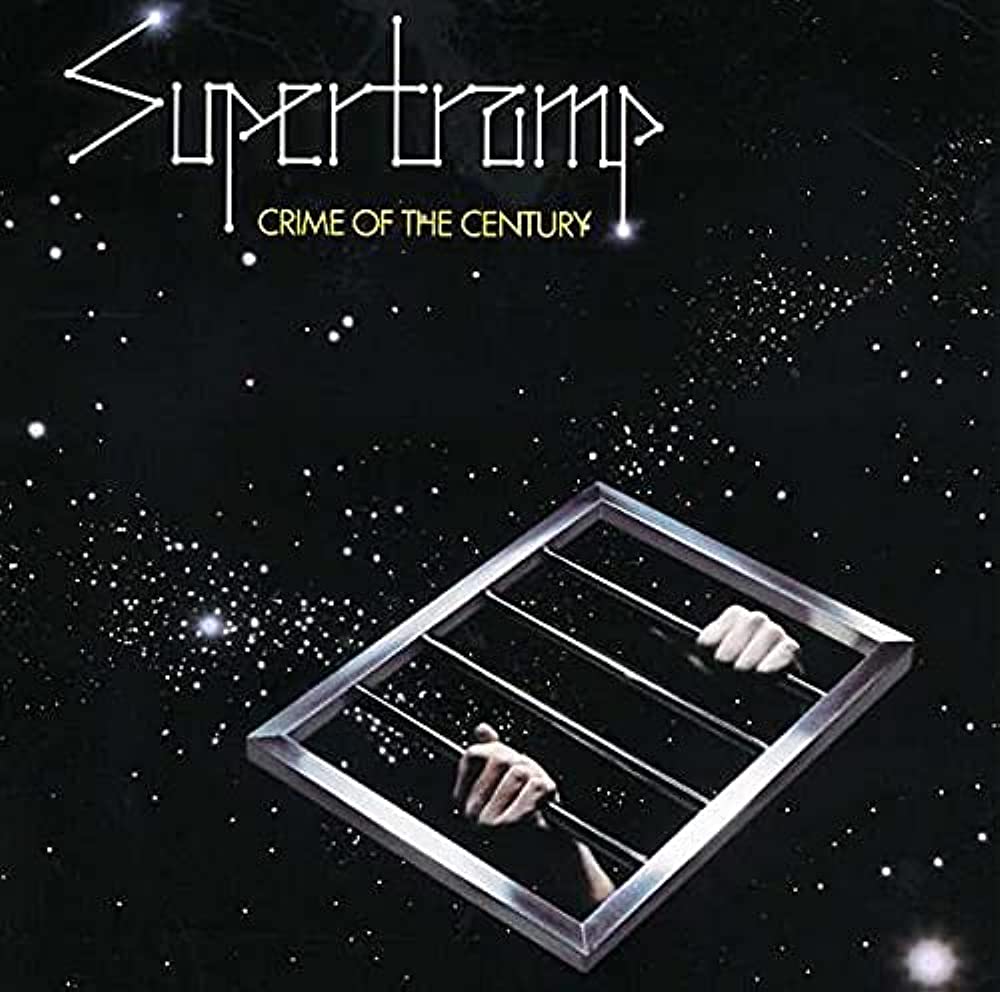

The working-class Davies and more poshly educated Hodgson had come together through an ad in the music paper Melody Maker in 1969. Hodgson told writer Jon Tiven that during Supertramp’s emergence, “We played every hole in England, we got every booking we could get our hands on. We didn’t even know where our next meal was coming from. In the early days we had a provider named Sam [the Dutchman Stanley August Miesegaes], who was a great guy, a millionaire who sort of took us under his wing and paid all our bills. . .we accumulated quite a large debt to him.” No wonder Supertramp dedicated their third album Crime of the Century, a breakthrough worldwide hit, “to Sam”: he’d stepped back from his role as band influencer and forgiven the debt before they entered Trident Studios in London for sessions with their new co-producer Ken Scott in February 1974.

The Crime of the Century lineup of Supertramp in 1979 (l to r.): John Helliwell, Bob C. Benberg, Dougie Thomson, Roger Hodgson, Rick Davies (A&M Records press photo; Greg Brodsky Archives)

Also new to the group were Dougie Thomson (bass), the American percussionist Bob Siebenberg (billed as Bob C. Benberg) and John Anthony Helliwell (saxophones/clarinet/backing vocals). Scott, already well-known from his work as engineer at Abbey Road and producer for David Bowie, Mahavishnu Orchestra and others, was originally recruited by A&M Records to remix a Supertramp recording called “Land Ho!”

“A&M loved it, but the band was iffy about it,” Scott told Joe Chiccarelli in 2010. A&M asked him to work further with Supertramp and sent over demos of new songs, which Scott described as “utter crap. It was like I’d get five seconds of a chorus and then it would go to another section, then it would stop, and then I’d get the ending of another song. It was completely random.” But when Scott went to see Supertramp perform live, he was sold. They just needed some good advice, and a way to channel all that haphazard energy, he figured.

For his part, Hodgson told Melody Maker that prior to recording the band was at Southcombe Farm in Thorncombe, Dorset, for three months rehearsing, “and we knew [we had a hit] before we went into the studio.” Hodgson and Davies, writing separately and together, had about 40 potential songs to choose from; only eight made final cut, and they were all prime.

Although to many listeners Crime of the Century sounds like a “concept album,” basically an examination of childhood and human psychology, with all the songs following similar characters and a pessimistic outlook, Hodgson has always insisted it wasn’t planned as a linked series: “It was just that it went together so well on stage that it appeared to be.”

Although to many listeners Crime of the Century sounds like a “concept album,” basically an examination of childhood and human psychology, with all the songs following similar characters and a pessimistic outlook, Hodgson has always insisted it wasn’t planned as a linked series: “It was just that it went together so well on stage that it appeared to be.”

Initial sessions were somewhat stressful, as Ken Scott and the band expressed a meticulous attention to sound design. “Sometimes it took a day and a half to get the snare drum down,” says Scott, “but I was looking for something and I knew what I wanted, and it just took that long. There were lots of tricks. I was determined not to use typical percussion. For instance, as opposed to maracas or tambourine, we had drum brushes shaking in front of the mics. You hear the wind and you get the same impression as maracas, but you just haven’t heard it before. There’s a musical saw on ‘Hide In Your Shell.’”

In another interview, Scott described getting down on his hands and knees, finding the right spot on the wooden floor to record a bang. And there were lots of sound effects recorded specifically to weave into the music, including the playground sounds on the opening track “School.”

Hodgson says he wrote most of “School,” with Davies contributing some lyrics and the piano solo. Talking to journalist Jeff Parets in 2010, Hodgson confirmed that his experience of boarding school drove the lyrics and sonic fingerprint of the track. It begins with nearly a minute of Davies’ lonely harmonica, before Hodgson sings the opening lines in his high, pleading voice, accompanying himself on guitar: “I can see you in the morning when you go to school/Don’t forget your books, you know you’ve got to learn the golden rule.” The sounds of children playing filter in, and a girl’s scream ushers in the full band. “Everything, especially that scream, does represent a lot,” Hodgson says. “School is a wonderful place. Obviously, it’s a school playground, but that scream does represent a lot more.” Talking to his younger self, Dodgson identifies the child’s doubts about adult authority and emphasis on conformity that his English education promotes.

If we situate Supertramp within the “progressive rock” genre, Crime of the Century takes its place with contemporary albums by Genesis, Yes, Strawbs, Gentle Giant, etc. One wonders if “School” exerted an influence on Roger Waters’ concepts for Pink Floyd’s The Wall a few years later, just as Dark Side of the Moon might have given Supertramp some ideas in 1973. As a declaration of intent kicking off the disc, “School,” and especially the multi-part instrumental center section, is a masterful mix of rhythms and colors, with each member contributing something special. The ending, “you’re coming along. . .,” is beautifully ominous.

Davies’ “Bloody Well Right” is just as intense, and proved itself a commercial success as well when it became a minor AM radio pop hit and major FM track when promoted as an American 45 rpm single in November 1974. Davies’ jaunty electric piano intro, with some jagged interruptions from the band, yields to a chunky saxophone riff, and a snaking, even humorous wah-wah guitar from Hodgson. The band’s almost in heavy metal mode when Davies starts singing a minute and a half in: “So you think your schooling is phony/I guess it’s hard not to agree/You say it all depends on money/And who is in your family tree/Right! You’re bloody well right!” The design of the chorus, with Davies tinkling a comical acoustic piano and Hodgson on a variety of guitars, is terrifically theatrical. A surprisingly funky sax-and-handclaps outro caps it all.

Hodgson’s “Hide in Your Shell” is a muscular but mid-tempo ballad, sung with a nice lilt, and benefits from very well-arranged backing vocals, a number of different keyboards chiming off each other, multi-tracked saxes, and some of the unusual percussion Scott elicited from Benberg. At nearly seven minutes, it doesn’t waste a moment.

Davies’ “Asylum” has an Elton John vibe at first and expands with each passing minute. The lyrics follow a down-on-his-luck character who might or might not be actually insane: “Don’t arrange to have me sent to no asylum/Well, it’s only a game I’m playing for fun/Yeah, I’ve been trying to fool everyone.” At two minutes, a majestic melody bursts into a towering drama, abetted by Richard Hewson’s cinema-worthy orchestral arrangement. Chimes ring out, an electric guitar wails, and from 5:40 onward a kind of audio mayhem personifies the disturbed nature of the protagonist’s mind. Side one is over—can Supertramp possibly bring this level of perfection to the flip side?

With Hodgson confidently leading “Dreamer” to begin side two, the answer seems to be “they sure can.” A delight for those listening on headphones, with multiple voices and keyboards occupying distinct left and right fields in the mix, the album’s shortest song, “Dreamer,” was coupled with “Bloody Well Right” for that single release. It was written by the 19-year-old Hodgson in 1969 on the brand-new Wurlitzer piano he set up in his mother’s house. At the time he made a rough 2-track demo, overdubbing vocal harmonies, with tin cans, lampshades, and cardboard boxes for percussion. Five years later he instructed Supertramp and Scott to copy that demo as closely as possible, but of course his co-workers improved on it at least a bit. The lyrics show a boyish delight: “Dreamer, you know you are a dreamer/Well, can you put your hands in your head? Oh no!”

Davies’ “Rudy,” according to Hodgson, is autobiographical, but the author doesn’t seem to make that claim. It’s a sad tale about a guy who “thought that all good things come to those that wait/But recently he could see that it may come/But too late, too late.” The longest track on the LP, it’s something of a short film, with nearly constant changes of mood and tempo, and some serious acting from the vocalists. Train announcements were gathered at Paddington Station, and crowd noises were recorded in Leicester Square. The middle section seems to be Hewson’s homage to Philadelphia International’s most danceable records, as the strings swoop delightfully and the beat pounds.

For Hodgson, his “If Everyone Was Listening” demonstrates the confrontation with “the fact that we have no control over anything.” The opening was inspired by the “all the world’s a stage” lines in Shakespeare’s As You Like It, which Hodgson reimagines as “The actors and jesters are here/The stage is in darkness and clear/For raising the curtain/And no one’s quite certain/Whose play it is.” There’s a lot to recommend on this track, but Hodgson’s vocal, Hewson’s strings and Helliwell’s clarinet deserve special kudos.

A Davies-Hodgson collaboration, the title track concludes the album, and serves as a summation of all the drama and musical risk-taking that’s gone before it. According to the band, it’s the song that’s emotionally moved the most listeners, maintaining its righteous anger through the decades: “So roll up and see/How they rape the universe/How they’ve gone from bad to worse/Who are these men of lust, greed and glory?/Rip off the masks and let’s see.” Another epic Hewson orchestral wrap-around, another great set of vocals, another almost exhausting hike to the summit of strong emotion.

Crime of the Century, released on Sept. 13, 1974, was Supertramp’s first Billboard Top 40 album in the United States, and achieved gold status a few years later, buoyed further by the success of the follow-up discs, Crisis? What Crisis? (1975), Even in the Quietest Moments. . . (1977) and Breakfast in America (1979). The 2014 two-CD deluxe edition adds a March 9, 1975, London concert that includes all eight album tracks in the program; the live album Paris featuring a 1979 performance is also chock full of Crime of the Century tunes.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Supertramp’s Breakfast in America

With lineup changes, Supertramp continued to record and tour off and on until 2012, took a break, and announced another series of shows in 2015, subsequently cancelled due to Rick Davies’ health problems. He died in September 2025. Hodgson did his own live performances, always including several tunes from Crime of the Century, until the Covid-19 pandemic put him on indefinite hiatus. [The album received a half-speed remastered edition in 2025.]

Watch Supertramp perform “Crime of the Century” live

The album, and others from Supertramp, are available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationSupertramp has always struck me as one of those groups that doesn’t get its full due. They were unique, and once COTC hit, they had a good run into the 80s.

A lot of their songs strike me as whimsical, both lyrically and musically. Also, they inspired a great parody, the appropriately-named “Topical Song”.

I was hooked from the first blast of “Bloody Well Right”. Went down to WT Grant, which was going out of business, and got the single for 59¢.

On the one hand, it’s unfortunate that Hodgson left after 1982’s “…Famous Last Words”. On the other hand, the fact that it took three years for their follow up to “Breakfast in America”, and that follow up was spotty at best, probably means it was inevitable. That said, “Brother Where you Bound” was better than it probably should’ve been. But “Free as a Bird”? Damn, I don’t know WHAT happened there, but to put it mildly, it was NOT good.