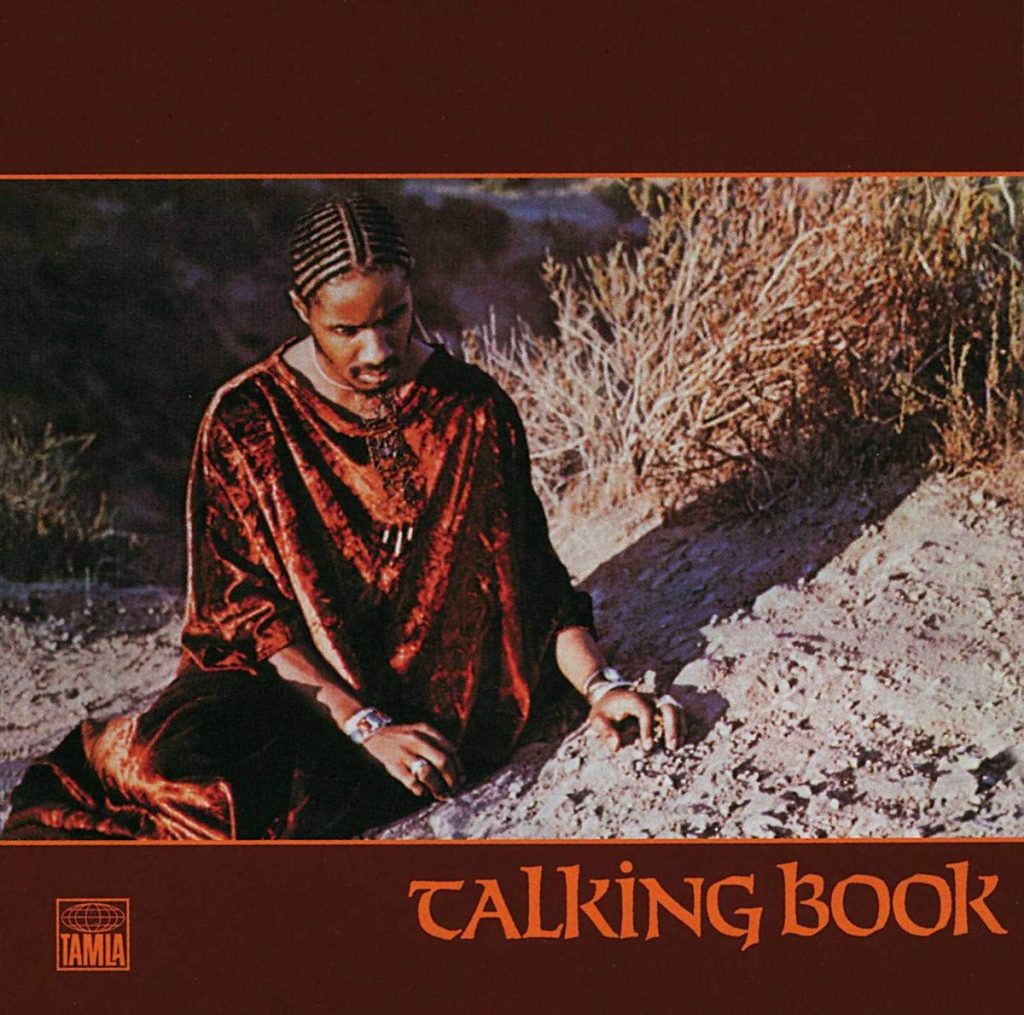

By the time Stevie Wonder entered the recording studio to put together what became his Talking Book album, he’d already placed no less than 30 45-r.p.m. singles on the Billboard Hot 100 chart and released 13 albums for Motown—astounding achievements especially considering he’d just turned 22 years old.

By the time Stevie Wonder entered the recording studio to put together what became his Talking Book album, he’d already placed no less than 30 45-r.p.m. singles on the Billboard Hot 100 chart and released 13 albums for Motown—astounding achievements especially considering he’d just turned 22 years old.

Wonder had taught himself to play drums at age three, the harmonica at six, and by the time he was 10 he was an adept pianist and songwriter, signing to Detroit’s premier Black record label at age 11. He’d lost his sight as a newborn, lived in poverty-stricken and abusive circumstances as a child, but didn’t let anything hold him back. He once told Oprah Winfrey that his mother thought God was punishing her through her son’s blindness, but he reassured her, saying, “Don’t worry about me being blind, because I’m happy.”

Working with electronic music pioneers Robert Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil as co-producers, Wonder recorded at George Martin’s AIR Studios in London, Electric Lady Studios in New York and two L.A. facilities, the Record Plant and Crystal Sound. Wonder’s keyboards dominate, especially the ARP and Moog synthesizers and Hohner Clavinet, but he plays many other instruments as well, drawing help from a talented group of session players and singers, including guitarists Ray Parker Jr. and Buzz Feiten, saxophonists David Sanborn and Trevor Lawrence, and background vocalists Deniece Williams, Jim Gilstrap, Lani Groves and Shirley Brewer.

Wonder found synthesizers liberating, telling NPR in 2000, “I was able to really create various sounds, bass sounds, and was able to bend notes the way that I heard them being bent, create different sounds of horns, string sounds and string lines, and really arrange them in the way that I felt I wanted them to sound.” Talking Book is certainly the sound of the future, blowing away many of the conventions of Black rhythm and blues.

That’s not to say the album is entirely avant-garde or experimental, or that it ignores tradition. It begins with one of Wonder’s most conventional ballads, the gorgeous “You Are The Sunshine of My Life,” which reached #1 as a single release and won a Grammy for Best Male Pop Vocal. The Fender Rhodes electric piano leads, with Daniel ben Zebulon’s congas and Scott Edwards’ electric bass in support.

The arrangement of this standard love song isn’t so standard, especially for an opening cut. The first voices heard are the smooth Gilstrap and Groves, before the top-billed artist Wonder enters at 45 seconds, with fervor: “I feel like this is the beginning/Though I’ve loved you for a million years.” Beautifully arranged and playful background vocals float through as Wonder lays down the old cliché “you are the apple of my eye” and somehow makes it work. He reaches his lowest notes on “this must be heaven,” which he sings with palpable humor. Wonder’s rhythm on drums, locked in with the congas, is now in double-time. It has the effect of gaining energy and speed while the lead vocal remains controlled and sinuous, a sort of tightly designed musical illusion.

The following track, the nearly seven-minute “Maybe Your Baby,” is where Wonder announces the album is going to break new ground and aim at some transcendent highs. He leaves the guitar to Parker and handles everything else himself, including Moog (imitating bass) and clavinet.

The funk is slow and broad, with plenty of air, and Wonder multi-tracks his vocals, with call-and-response, cries of joy, exhortations and yelps. About halfway there’s room for a guitar solo and a bridge section that gets us firmly into the headspace where Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix jam. As the funk-and-grind gets even deeper through repetition, and Wonder shouts and sings and cavorts (his voice sped up at points), it sounds not unlike what Prince would do 15 years later.

Wonder plays everything on “You and I (We Can Conquer The World).” It begins with him handling the room-filling TONTO (The Original New Timbral Orchestra) polyphonic synthesizer, which Wonder first encountered on the album Zero Time by TONTO’s Expanding Headband the previous year. One day in his New York apartment, the English bassist-turned-tech-wizard Malcolm Cecil heard a ring at the door, and found “a Black guy in a pistachio jumpsuit” asking for entry. Cecil and his producing partner Bob Margouleff worked with the enthralled Wonder on Music of My Mind, Talking Book and two subsequent albums of equal import.

“You and I” displays Wonder’s delicate touch on both TONTO and acoustic piano. His echo-laden vocal is free-flowing and highly emotional. He pays tribute to protégé, co-writer and wife Syreeta Wright as their 18-month marriage ends (they remained close until her death in 2004). “I am glad at least in my life I found someone/That may not be here forever to see me through/But I found strength in you/I only pray that I have shown you a brighter day,” Wonder sings. “Don’t worry what happens to me/’Cause in my mind, you will stay here always.” He later explained, “We loved each other, but we were better friends when we weren’t married than when we were. When I was younger, maybe I fell in love a lot.”

Related: 1972 in rock music

“Tuesday Heartbreak” adds only David Sanborn’s sax and Williams and Brewer on backing vocals to Wonder’s one-man-band, and is a cousin to hits like “I Was Made to Love Her” and “Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Da-Day” without doing anything remarkable. Thankfully, “You’ve Got It Bad Girl” ends the first LP side on a real high. Co-written with Yvonne Wright (no relation to Syreeta), it’s a jazzy melody that interweaves Wonder’s multi-tracked vocal with Gilstrap and Groves. Wonder’s Moog bass is especially impressive, and he continues to find brilliant colors within TONTO’s circuitry.

Side two begins with Wonder’s drumming, and therein lies a tale. He says he imagined pretty much the whole idea for “Superstition” while on tour with the Rolling Stones in 1972, as he was conceiving Talking Book. “I think that the reason that I talked about being superstitious is because I really didn’t believe in it, in the different things that people say about breaking glasses or the number 13 is bad luck. And to those, I said, ‘When you believe in things you don’t understand, then you suffer.’”

Related: When Stevie Wonder toured with the Rolling Stones

But according to most accounts the song was also supposed to be Wonder’s gift to Jeff Beck. As Beck recalled in the book Guitar Greats, “There was a time when I was pretty bored with my music, and I think somebody at CBS asked me what I wanted to do. I said I loved Stevie’s stuff, so they quietly broke it to him that I was interested in doing something together, and he was really receptive. The original agreement was that he’d write me a song, and in return, I’d play on his album, and that’s where ‘Superstition’ came in.”

He elaborated in Annette Carson’s book Jeff Beck: Crazy Fingers, saying, “One day [at Electric Lady] I was sitting at the drum kit, which I love to play when nobody’s around, doing this beat. Stevie came kinda boogieing into the studio: ‘Don’t stop.’ ‘Ah, c’mon, Stevie, I can’t play the drums.’” Then Wonder played a line on the clavinet, and Beck thought, “He’s given me the riff of the century.” They finished a rough demo immediately.

Motown’s Berry Gordy put his foot down after hearing the nascent “Superstition”: no way was such an obvious hit going anywhere outside Talking Book. Beck, Bogert and Appice eventually released their rock version shortly after Wonder’s recording reached #1 as a Motown single. And Beck does appear on Talking Book, playing on “Lookin’ for Another Pure Love” and “Tuesday Heartbreak” (uncredited); he says there are several other as-yet-unreleased recordings with Wonder as well. Beck eventually agreed that keeping the song for Wonder “was the right decision, but we were gutted, you know, totally. We would have had a monstrous, monstrous hit.”

Watch Beck, Bogert and Appice perform their version of “Superstition”

Wonder’s “Superstition” clavinet launched a thousand acolytes (jam band keyboardists are very susceptible, e.g., Phish’s Page McConnell and Disco Biscuits’ Aron Magner). Trevor Lawrence and Steve Madaio provide the rollicking tenor sax/trumpet riff for this iconic landmark in soul and rock music.

“Big Brother” is 100 percent Wonder (clavinet, percussion, Moog bass, vocals), and contains the only appearance of his always startling and virtuosic harmonica playing.

“Blame It On the Sun,” a co-write with Syreeta, is an unusually structured ballad, which includes some baroque touches from TONTO and harpsichord. On anyone else’s album it’d be a standout composition, but here it doesn’t quite rise to the overall level of achievement.

Talking Book ends with “I Believe (When I Fall in Love It Will Be Forever),” a co-write with Yvonne Wright that is truly sublime. The melody soars and dips, Wonder’s multi-tracked vocals are simultaneously highly emotional and superbly controlled, and once more the clavinet and Moog give Wonder an entire toolbox of effects. The track also contains a neat musical trick, as it deftly goes from ballad to banging funk and back again, with Stevie Wonder responsible for every sound and nuance.

The album, released Oct. 28, 1972, was among the top sellers of 1972 and 1973, reaching #3 on the Billboard Top LPs chart. At the 1974 Grammy Awards, Wonder got Best Male R&B Vocal, Best R&B Song and Best Male Pop Vocal for “Superstition” and “You Are the Sunshine of My Life,” and Cecil and Margouleff received the nod for best engineered non-classical album, plus Wonder’s subsequent album Innervisions was Album Of the Year. Some prophets are honored in their own country!

In that NPR interview, Wonder remained humble about Talking Book, saying it was more about expressing his emotions than politics: “I wanted to just express various things that I felt. . . the passions, emotion and love that I felt, compassion, the fun of love that I felt, the whole thing in the beginning with a joyful love, and then the pain of love.” The original LP sleeve was embossed in braille, with the album title and artist’s name and a message: “Here is my music. It is all I have to tell you how I feel. Know that your love keeps my love strong.”

[Wonder’s extensive recorded legacy, including a 2024 vinyl edition of his Definitive Collection, is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Watch Stevie Wonder perform “Superstition” live in 1974

Bonus Video: Watch Stevie Wonder jam with the Stones on his “Uptight” and their “Satisfaction” live in 1972

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationGreat assessment of a great album. Thanks.