When Robbie Robertson Reunited With The Band Photographer Elliott Landy

by Greg Brodsky

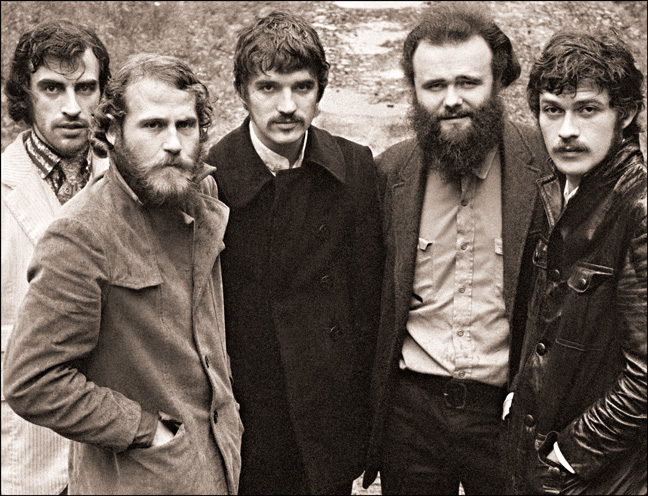

The Band, Music From Big Pink album photograph, Woodstock NY, 1968 (L-R: Rick Danko, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson, Robbie Robertson) (Photo © Elliott Landy; used with permission)

Robbie Robertson can be forgiven if it seems like the weight of the world has been lifted from his shoulders. He was speaking at the Q&A session that followed the November 6, 2019, U.S. premiere of Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band, director Daniel Roher’s feature documentary about the influential music group. The film served as the opening night presentation at the 10th edition of the annual DOC NYC festival.

It was a particularly busy period for Robertson. The musician, born July 5, 1943, released a solo album, Sinematic, that September and wrote the score for Martin Scorsese’s acclaimed film, The Irishman. A few weeks later, a 50th anniversary edition of The Band’s 1969 self-titled, second album arrived.

Once Were Brothers follows Robertson from his early life in Toronto and on the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve, in Southern Ontario, as he becomes an adept guitarist and songwriter. It follows his path as he joined drummer Levon Helm, and then keyboardists Garth Hudson and Richard Manuel, and bass guitarist Rick Danko, as the touring musicians for singer Ronnie Hawkins; then as the backing band for Bob Dylan in 1965 and 1966. That set the stage for the five “brothers” to band together in their own group.

Watch the trailer for Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band

The film, with plenty of previously unseen footage–”[It was] a question of trying to leave no stone unturned and find every single piece of archive,” said Roher–is at times exhilarating, thanks to the stunning footage of The Band rehearsing in the studio. Yet, at other moments, the movie is numbing for the painful way in which the five of them came apart just as they were achieving acclaim for their influential recordings.

Robertson and Roher had been asked by the moderator about the use of scores of images in the film that had been taken by photographer Elliott Landy in the late ’60s. Landy, in the audience, was asked to stand up. “My buddy,” Robertson said fondly.

“At that time with the Band… we lived up in the mountains in Woodstock, New York,” Robertson said, “with Bob Dylan and [manager] Albert Grossman and everybody. And we didn’t want anybody coming in. We didn’t want anybody walking on our lawn.

“And we invited Elliott Landy in. He was the only one who came in and saw what was really going on. He was part of the family. Thank you, Elliott.”

Roher, speaking about Landy’s contribution to the film, added, “The look of the group, sort of the old western, Mathew Brady inspiration, that the group is known for–that was because of Elliott’s creative vision.”

At the afterparty that followed the U.S. premiere, two legends in their respective fields caught up on old times, and posed for photos together. On his Instagram, Robbie Robertson wrote, “Hanging with my old partner in crime Elliott Landy. Nice to see him on this side of the camera.”

View this post on Instagram

Beginning in the late ’60s, Landy photographed many of the biggest names in rock music. His images of Dylan and Van Morrison are featured on their album covers and his work has appeared on the covers of numerous magazines from Rolling Stone to Life.

Grossman had seen Landy’s photos of another one of his clients, Janis Joplin, and, trusting his instincts, offered Landy an assignment to “take some pictures in Toronto.”

“Of who,” he asked.

“They don’t have a name yet,” was the reply.

He shot the members of The Band during the next two years, in a variety of settings. On Easter weekend, 1968, he photographed them at their house they called “Big Pink.”

The Band, The Band album cover photo, John Joy Road, Woodstock, NY, 1969. (L-R: Richard Manuel, Levon Helm, Rick Danko, Garth Hudson, Robbie Robertson) (Photo © Elliott Landy; used with permission)

Over time, Landy shot The Band individually and collectively in the Woodstock area and also in California during the recording of The Band album and their debut performance as The Band at San Francisco’s Winterland. His photos were used on the group’s first two LPs, Music From Big Pink and The Band. Those albums include songs like “The Weight,” “Up on Cripple Creek” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” that would become the group’s signature tunes.

Elliott Landy has announced a second volume of photos that he took of The Band. Ten years after the first edition that had long since sold out, the legendary photographer will publish The Band Photographs: 1968 – 1969 Two-Volume Set. The hardcover title, 12×12 inches, joins the two editions, with a combined 352 pages and nearly 400 photos. The book, via publisher Weldon Owen, arrives November 25, 2025. It’s available for pre-order in the U.S. here in Canada here and in the U.K. here. To purchase any of Landy’s fine art prints, click here.

Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band, was executive produced by Scorsese, Brian Grazer and Ron Howard. It includes illuminating interviews with Bruce Springsteen, Eric Clapton (“Music From Big Pink changed my life,” he says), Scorsese, Van Morrison, Peter Gabriel, Taj Mahal, Dominique Robertson and Ronnie Hawkins.

Once Were Brothers film director, Daniel Roher, arriving at the afterparty on the night of the U.S. premiere (Photo © Greg Brodsky)

Its filmmaker is a fellow Canadian. And though only in his mid-twenties, he had embraced the music of The Band, and many of their peers, such as Neil Young and Joni Mitchell. “There’s a moment in the film when Robbie describes playing Music From Big Pink for Bob Dylan,” he said. “And Dylan says, ‘Who wrote that? Whose song is that?’ And Robbie says, ‘I wrote that.’ And Dylan says, ‘You wrote that? That’s your song?’ And my experience at that moment was when Robbie saw the rough cut and he said, ‘That’s your movie? That’s what you made?’ And that meant a great deal to me.”

Said Robertson, “Daniel had to figure out [how] to focus on a certain period in time. All of these stories… he found a way to make this so moving and so emotional. And I didn’t see this coming. When I saw the rough cut, I thought, this is quite beautiful. And the fact that it was touching to me and that he had the sense to go in the direction like that, which is night and day to what a lot of these [music documentaries] are, that was very rewarding.”

The film is bookended with riveting performances of The Band rehearsing “Up on Cripple Creek” in Woodstock, and with their performance of “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” at The Last Waltz, their final concert, at Winterland, in 1976.

“Not only did they have the incredible writing, but they had three of the greatest white singers in rock history,” says Springsteen. “To have any one of those guys would be the foundation for a great band. To have three of them in one group, that was just loaded for bear.”

Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band, is available for streaming or purchase in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here. The Band’s recorded legacy is available here.

The Last Waltz lives on thanks to its 1978 concert film, directed by Scorsese.

Robertson says they talked about performing together once more. They never did.

Related: The Last Waltz – An Audience Member Revisits

Watch the video for “Once Were Brothers,” from Robertson’s 2019 solo album, Sinematic

Robertson died on August 9, 2023, at age 80.

For four decades, Robertson produced music for Martin Scorsese’s movies, and now the story will finally be told about the rock legend’s collaborations with the iconic filmmaker—in Robertson’s own voice. Insomnia, described as an intimate portrait of a remarkable creative friendship between two titans of American arts, will be published on November 11, 2025, via Crown. It’s available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI’ll start out by saying two things as a disclaimer: 1) I wasn’t there, so my feelings are based on what I’ve been able to see through the lenses of my perceptions based on what’s been disclosed to me from other’s sources. 2) I’m a fan of Robbie Robertson’s solo records.

That said, I don’t trust Robbie Robertson with regard to all things related to The Band. The fact that he’s always seemed too comfortable being the mouthpiece for them from “The Last Waltz” and forward, while the other members stayed more or less ominously quiet said something to me. Then there’s the fact that post band, most of the former members, except for, or without, Robertson, seemed amenable to having contact, or even making music, for the short time many of them were still with us. To me, that inferred a lot about what had not been said. As someone who’s been in bands for much of my life since I was a child, I understand the almost inevitable dynamics that form in bands and take on their own shape and internal psychological motivations and underpinnings. As a result, I can often spot the littlest details among group members that tell a lot about what’s going on inside them and inside a band. And whether I’m wrong or right, what I felt about “The Brotherhood” is that Robertson, as talented as he may be, was also an opportunist when it came to harvesting credit for the talents of his musical brothers. Much has been made in many groups for how songwriting credits are shared and accredited. It’s often difficult to discern where and when a song is actually “written.” The Doors went through similar issues at times deciding if one person actually wrote some of their songs, or if it was a collaborative effort. I always got the feeling that it was the same situation with The Band. The fact that Robertson is credited as the songwriter for ALL of their songs seems somehow unrealistic, especially as their catalogue covered such a wide range of sounds and styles, much of them having very little to do with guitar. In any case, as the charismatic spokesman, Robertson seemed always in a position to willingly take credit for the cumulative original sound and style of The Band. And something in my gut just never bought it. Perhaps it’s the resentment toward him that I sensed from the other members. Perhaps it’s the fact that he’s not really a very good guitar player or singer, though that certainly doesn’t preclude the ability to write songs. But as his solo records don’t even resemble any of the sounds and stylings of The Band’s recordings, one has to wonder where that all came from. Now as the next to the only person even alive to tell the tales — the only other one being The Band’s musical genius who seemingly doesn’t even speak — Robertson is in a greater position than ever to write his own history of the group, and his place in it. And sure, he’s maintained that high profile over the years since, palling around with Scorsese, Clapton, and many other elites of that generation. They welcome him as the representative of The Band’s creative force. It’s a cozy fit for all concerned, and who’s to challenge it? There’s just special kind of lingering sadness involved with representing a group of supremely talented people, some of whom ultimately took their own lives, and lording yourself out as the master of all he surveyed in that realm. If you know The Band, and really feel their music and their souls, in the back of your mind you have to wonder if Robertson played some part in the tragedy that ultimately became of its members lives.

There’s always drama in bands when egos are aloud to clash and I’m sure it was no different here, but they chose to keep it to themselves unlike some other train wrecks such as Pink Floyd, CSNY etc.etc….Can’t predict the future, cant forget the past, feels like any moment could be the last! Thanks for the tunes Robbie R.I.P. Godspeed and God Bless

Loved their music, loved his music. Watching them throughout their amazing career and afterwards makes me glad I never was in a band. Didn’t look like much fun in the long run.