Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and an utter lack of it is nothing to sneeze at either. So it is with Queen, whose immense success never spawned a movement of sound-alike bands, because parroting its act obviously would have been a fool’s errand.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and an utter lack of it is nothing to sneeze at either. So it is with Queen, whose immense success never spawned a movement of sound-alike bands, because parroting its act obviously would have been a fool’s errand.

Queen’s heyday featured multiple sonic calling cards: There was the shiny electric ring of the Red Special, Brian May’s spectacularly distinctive, legendarily homemade guitar. They boasted the singular rhythm section of John Deacon on bass and Roger Taylor on drums, conduits of a wide musical spectrum’s influences. Most of all, as a sui generis enterprise, to paraphrase women’s basketball coach Geno Auriemma, they had Freddie, and everyone else didn’t.

Freddie Mercury was an embarrassment of frontman riches: Musically adept, artistically ambitious and utterly theatrical, he was a legitimate rock ’n’ roll visionary. From rollicking excess to gossamer balladry, he covered every compositional quadrant, and with a bold, memorable singing style, was one of music’s all-time great finishers. How to qualify the band’s music that followed his 1991 death is a matter of personal taste, but as a practical matter, he was irreplaceable.

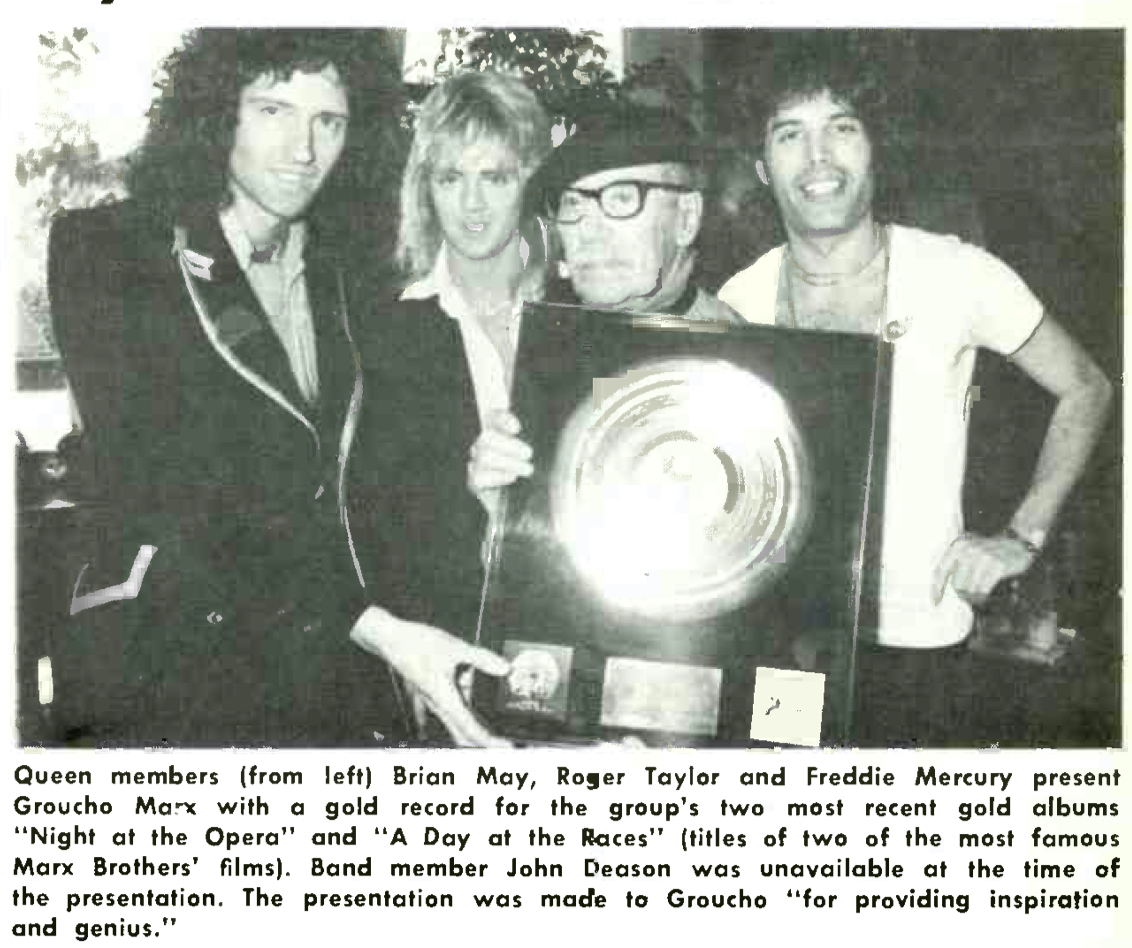

The members of Queen presented Gold Record awards to Groucho Marx who inspired the album’s title

Nowhere can the group’s inimitability be heard more clearly than on its fourth record, A Night at the Opera, released on November 21, 1975. Acknowledged in its time as the most expensive album ever recorded, like a Hollywood blockbuster whose oversized budget is visible on the screen, A Night at the Opera is a showy spectacle that revels in its bombastic production touches. Deservedly renowned, it is wildly, and often wonderfully, uneven.

Related: Queen films “Bohemian Rhapsody” video, 1975

The collection’s first song has aged less gracefully than the rest of the project, but it always was a bit of a mistake. “Death on Two Legs (Dedicated To…)” is a snapshot of a moment in time that, with its two primaries now dead, seems even more trivial and unworthy of inclusion than it did when new.

It addresses Queen’s clearly ugly breakup with their original management company Trident. Manager Norman Sheffield is its target, and receives a thorough kicking, from a parade of insults that include “misguided old mule” and “big-talking small fry” to a suggestion that he consider suicide. It’s an unpleasant song, driven by Mercury’s passions and supported by his fellow band members. A more effective expression of anger than art, as a piece intended for an audience, it’s too specific for its own good.

Its message is easy enough to gloss over if a listener notes only its forceful, enveloping throb, which establishes the collection’s robust production philosophy. From off in the distance, a piano piece is joined in progress—Trident allegedly denied Mercury a piano on which to write songs while the group was developing the record, so even that has an edge in context—which soon gives way to soft alarms and screeches before teleporting into a mesh with May’s roaring Red Special. The tune never finds its balance (and it’s clearly not looking very hard) as it thumps and churns, mingling fist-pumping enthusiasm with gleeful melodrama, all while Mercury jabs at lyrics and digs into his bottomless supply of vocal self-assuredness.

The album’s sequencing is straight out of Dr. Seuss. Oddball course corrections and jarring genre leaps abound, and clever segues give them a hard sell, beginning with the major veer from the opener to the plinking “Lazing on a Sunday Afternoon.” It’s a hokey, brief palate cleanser, and Mercury milks its goofy, old-timey lilt as enthusiastically as he did the throwback fun of “Bring Back That Leroy Brown” on the preceding year’s Sheer Heart Attack. Alongside a fluid piano trickle, vocals evoke technology gone by, trimmed with an echo derived from playback in a tin bucket. May puts a bow on the proceedings with decorative shredding, and in less time than it took to write this paragraph, it’s time for another gear change.

That’s almost literally the case as Taylor revs the delightfully overboard “I’m in Love With My Car.” One of Queen’s most appealing traits was their earnest commitment to foolishness, a quality that fuels this number’s success. The song luxuriates in a spectacular sense of the absurd, swaddled in a mesh of guitar etchings and piano percussion amid a muscular, chorus-augmented throb. Racing engines mesh with growling guitars, and amusing innuendo such as, “With my hand on your grease gun/It’s like a disease, son” floods the tune. It’s unashamedly silly, signature work.

Related: Taylor is on our list of Rock’s Singing Drummers

Conversely, “You’re My Best Friend” is a triumph of sincerity, a ballad with spring to spare. Built around the lively dynamic between a grit-lined synthesizer pulse and Taylor’s shapely drum backbone, there’s plenty more besides. The song is nearly a minute old when its until-then-straightforward design is upended: Mercury ignites the line, “Ooh I’ve been wanderin’ ’round” from the right, and a chorus sneaks in from the left to balance it out. When the next verse arrives, it’s back in the center, but May enters with poised electric gilding to complement the overall flow. Deacon’s composition is a rich vein, and its nuanced vocal reinforces that Mercury’s effusiveness works on a personal level as well as a dramatic one.

Side one is barely half over at that point, and its curiosities continue. May drives the homespun skiffle bounce of “’39” vocally and musically, playing with stereo positioning while telling a story of interstellar exploration with unfortunate consequences. Splashing a heavenly choir atop a toe-tapping mesh of bass, drums and tambourine, it’s a colorful bit of folksiness.

Related: “39,” Brian May’s homage to space exploration

That gives way to the by-comparison-conventional “Sweet Lady,” which finds Mercury aggressive, exaggerated and quite convincing, even when he’s declaring, “You call me sweet/Like I’m some kind of cheese.” It’s overdone, but with charm.

The side closes in labor-intensive fashion, generating Vaudeville chic in the springy “Seaside Rendezvous.” In addition to the stylistic curveball it tosses, the tune is a tour-de-force of multi-track song building, as Mercury and Taylor vocally imitate an assortment of instruments, substantially predating Bobby McFerrin with spot-on impressions of clarinet, tuba and a thoroughly jaunty sliver of kazoo. Down to its tap dance interlude performed with thimble-topped fingers, it’s an entertaining collage of mimicry, but never at the expense of its infectious energy.

The chops on display in “The Prophet’s Song” are simpler to quantify; its inflated, prog-leaning expanse is a playground in which Mercury runs free. His voice lands everywhere in a song that is big, blustery and, at over eight minutes (the longest in Queen’s catalog), drags more than a little. Mercury executes a vocal canon that showcases his versatility and flexibility, and May’s guitar portions late in the song grind and ooze intensity, adding heft to Mercury’s bravado. The whole is vast but not consistently enticing, a piece very much of its time that resonates less in this one.

The sparsely adorned piano ballad “Love of My Life” finds Mercury gently kneading, selling its plaintive, earnest angst with vocal support from a plush chorus that lands ahead of his lines. May colors the arrangement with mellow guitar washes that float nearby, sharp edges for the most part removed. A harp also rears its head, for what may or may not be good measure, but for the most part the song is stripped to essentials, maximizing its potent intimacy.

“Good Company” is another May-driven diversion, making a reasonable argument that the collection needed a ukulele-driven hop. May displays mimicry skills on par with the Mercury/Taylor showpiece, as he dishes out a Dixieland jazz band simulation on his Red Special.

And then there’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.” If ever there existed a definitive example of a whole being greater than the sum of its parts, it’s the song his bandmates called “Fred’s Thing” during recording, which took three weeks, with work split between five studios. The result is remarkable, a scattershot array of effects and ideas brought together into a cohesive framework.

This ad for “Bohemian Rhapsody” appeared in the Dec. 13, 1975 issue of Record World

A simple roadmap to the song does it little justice. Mercury’s multi-tracked vocal introduction gives way to an arch piano ballad. May’s guitar provides ascending drama in a brief interlude, and then the whole thing goes off the rails with an opera section that, despite the fair warning of the album’s title, comes out of nowhere. That gives way to grinding guitar rock, which resolves to a lustrous piano and lyrical exhale. In those terms, it sounds like a mess.

And yet the song avoids every trap, and works because it is incredibly nimble. In just under six minutes, its identity changes five times, shedding each almost as soon as it is established. Even the most outlandish reach is not around long enough to be identified as such. It sounds like nothing else, and yet is structured in a way that makes it seem comfortable—its rock is grabby, its balladry spacious and its opera has inescapable hooks. Among its great achievements is reveling in the highly unusual without ever becoming weird.

Watch the video for “Bohemian Rhapsody”: Masterwork, novelty, just plain fun

“Bohemian Rhapsody” is prog rock for listeners with no intellectual illusions, hard rock for people who like pop, and grandiloquence so smartly crafted that it that doesn’t even require an open mind on the part of the listener. Wonder at the song’s generations-deep appeal and whether it’s a masterwork or novelty, but make no mistake: it’s plain fun. It is a microcosm for the full project’s accomplishment, highlighting a spare-no-expense approach that welcomes experiments, and has ample room for a little bit of everything. Rich with excess without turning excessive, it includes everything a spectacular ending requires.

And yet, there’s one more, akin to a cool down from a challenging workout. Brian May serves up “God Save the Queen” ala Hendrix on “The Star Spangled Banner,” in a lively, loving bit of homerism for the British band (though listeners across the Atlantic might hear it as “My Country, ’Tis of Thee”). Decorating with traces of studio grit that enhance character, May layers multiple tracks, forging an expansive sonic alloy that lets freedom—and the Red Special—ring. It’s a fitting finale, akin to a TV station shutting down for the night with the playing of the national anthem, closing a day’s programming that no other band could have created.

A Night at the Opera became Queen’s first (of many) albums to reach #1 in the U.K. It was also represented their U.S. breakthrough, peaking at #4.

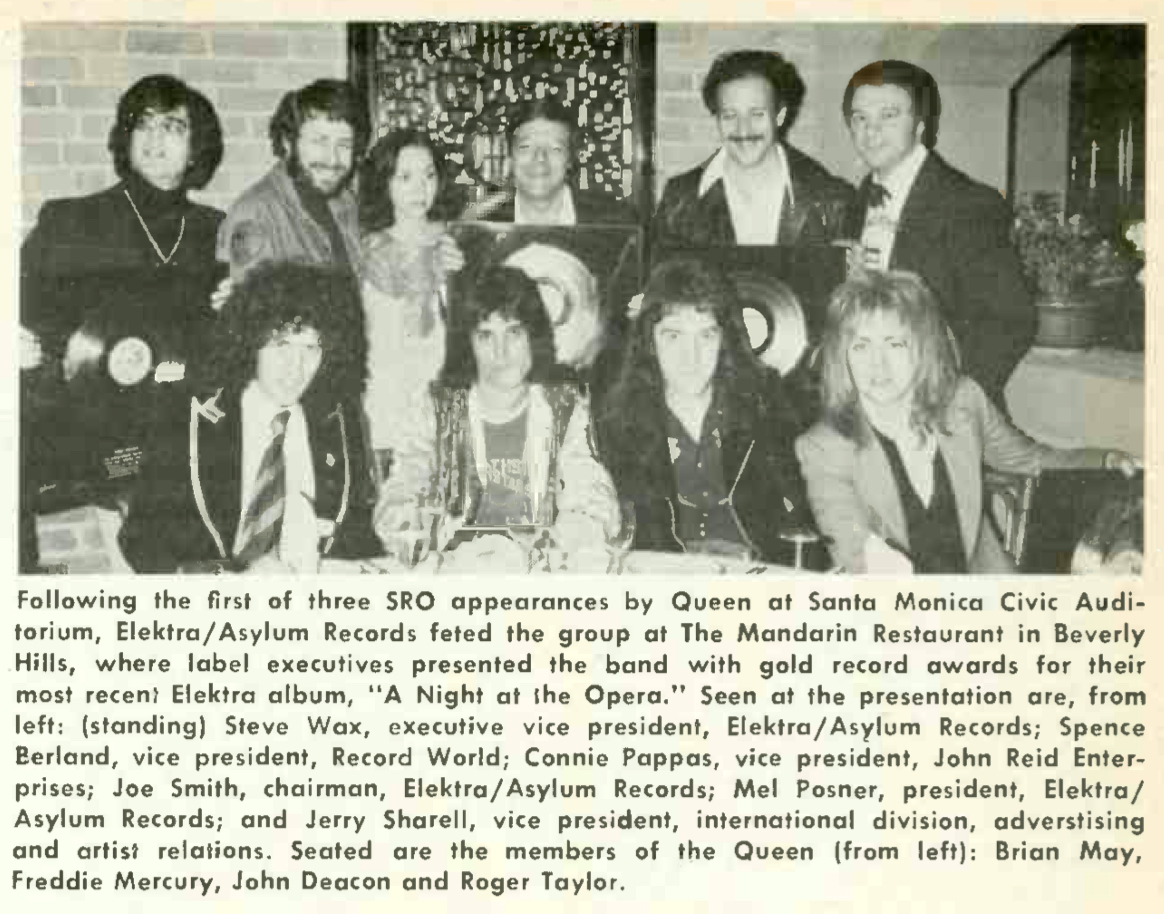

This photo of the band accepting their Gold Record award appeared in the March 27, 1976 issue of Record World

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI will never forget the first time I heard “Bohemian Rhapsody” on the radio. I was riding in a car with a friend down in Tampa, Florida, and that song came on the radio. I was transfixed. I had never heard anything like that–but then, neither had anyone else. It was, and remains, a stunning masterpiece of musical ingenuity.

I think this is the second time in recent months that I’ve read about “Death on Two Legs” not aging well because of the lyrical content. I don’t think most people had any idea what that song was about when it came out, and maybe still don’t. I didn’t until maybe about 10 years ago. And I don’t care. Brian May’s various guitar theatrics throughout make that song what it is, not the message towards a former manager.