Frey & Souther’s ‘Longbranch Pennywhistle’: Not Ready for Prime Time Players

by Mark Leviton

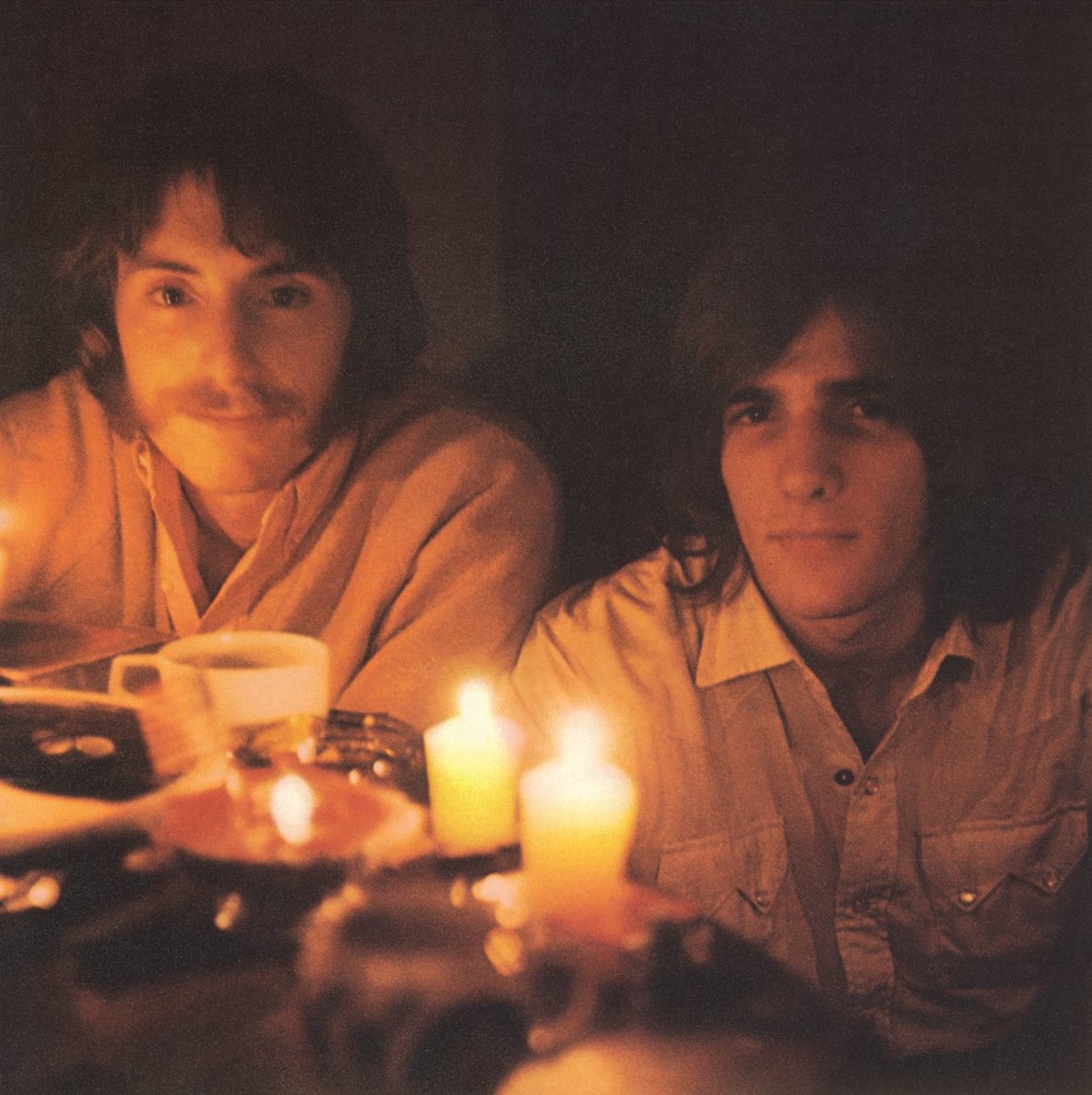

J.D. Souther and Glenn Frey

In Los Angeles in the early ’70s, the bar at the Troubadour, a cozy, wood-paneled nightclub on Santa Monica Blvd., was the place to see and be seen. Just downhill from the famed Sunset Strip and a couple miles east of UCLA, the Troubadour occupied a geographic sweet spot. It was presided over by the cantankerous owner/booker Doug Weston, who was known for keen talent-spotting and exploiting his economic leverage over struggling aspirants to show business careers.

For more than a decade, a free admission “hootenanny” had been held every Monday night, with 10 to 15 acts performing a song or two. Unknown musicians and comedians checked each other out, as they were in turn evaluated by various talent agents, managers and record company execs. “The Troubadour was like a café society,” Linda Ronstadt told journalist Johnny Black. “Everyone was in transition. No one was getting married, no one was having families, no one was having a particular connection…so our connection was the Troubadour. We used to sit in a corner of the Troubadour and dream.”

Glenn Frey and John David Souther spent a lot of time at “The Troub,” McCabe’s Guitar Shop and other local venues, performing as Longbranch Pennywhistle—each picked a single-word band name and then combined them—or jumping on stage to accompany anyone in need of backup. Souther, a country music fan, had moved to California from Amarillo, Texas, in 1967, later telling writer Barney Hoskyns, “I think I knew exactly what I would find there. I even knew what the air would smell like. It was ozone and ocean and automobile exhaust and eucalyptus.” Frey had been playing mostly rock and soul music in Detroit when he got hooked on the Southern California mythology he heard in “Good Vibrations”-era Beach Boys records: “I saw copies of Surfer magazine. I took acid and bought the first Buffalo Springfield album. I got into this whole ‘California consciousness.’”

Frey told Rolling Stone, “I came out here chasing my girlfriend. John David was going out with my girlfriend’s sister and I met him my first day in California.” Both men were good-looking long-hairs, and cultivated as much cool and mystery as they could, considering they were perpetually broke. Scenester-writer Eve Babitz, who often helped the guys prop up the bar, recalled, “J.D. once told me he spent his first six months in L.A. learning how to stand.”

Ronstadt agrees the jockeying for position could have its humorous aspects: “It’s like the musician pool and the sex pool, you know? Like, if you needed a new player there was this big tank full of whoever’s not busy at that point, so you just reach in and get one. Or, ‘Gee, I just broke up with my old man, I need a new honey’—reach into the same tank.”

The tiny independent label Amos Records gave Frey and Souther’s sort-of-Everlys-on-acid folk-country duo the chance to record. Amos owner Jimmy Bowen had had some success as a performer himself in the ’50s, and helmed big hits for Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr. and Dean Martin as a Warner/Reprise producer in the ’60s. Eventually taking a “supervised by” credit on the Longbranch Pennywhistle LP, Bowen called upon top-rank L.A. and Nashville players for sessions at Hollywood’s TTG Studios, with producer Tom Thacker and engineers Mic Lietz and Chuck Britz, who’d worked with Johnny Rivers, the First Edition, the Beach Boys and many others. Guitarists Ry Cooder and James Burton, drummer Jim Gordon, steel guitarist Buddy Emmons, fiddler Doug Kershaw, pianist Larry Knechtel and bassist Joe Osborne backed up Frey and Souther on vocals and guitar.

Released in September 1969, the album did absolutely nothing to help them establish a career. Bowen refused their request to record a second album with Neil Young’s producer David Briggs, and Amos itself closed up in 1971. Souther and Frey moved into a dirt-cheap duplex in Echo Park with the successful songwriter Jackson Browne, and kept struggling. Fame was indeed just around the corner.

Many years later, Souther didn’t think much of Longbranch Pennywhistle, telling Goldmine magazine, “We were new songwriters, and I didn’t have any illusions about writing the song of songs then.” The opening “Jubilee Anne” (“a livin’ little piece of California country soul”) is Souther’s declaration of intent, with the expert musicians handling a peppy arrangement and the duo singing and harmonizing with substantial appeal. The song itself wanders outside the lines a bit too much, perhaps revealing that amateur status Souther detected decades afterward.

The same can’t be said for Frey’s straight-ahead “Run Boy Run,” which can be favorably compared to what Gram Parsons was doing with country-rock at about the same time. If it ended up in the setlist for Frey’s next band the Eagles it would fit right in.

Frey’s mid-tempo ballad “Rebecca” is a trifle with some awkward lyrics (“She looked on me sweetly/I told her I couldn’t stay/I reasoned discreetly/Yet I couldn’t turn away”). It does have some lovely harmony vocals; it recalls a new soft-rock group that Jim Gordon was playing with at the same time, Bread. “Lucky Love” is helped greatly by Kershaw’s Cajun fiddle and another terrific duet vocal. It wouldn’t be out of place on Poco’s debut LP, released only a few months before Longbranch Pennywhistle.

Osborne and Gordon lay down a loping Bakersfield-country-style rhythm for “Kite Woman,” which is among the most Everlys-ish of all the tracks. The lyrical conceit unfortunately doesn’t live up to the instrumental backing: “She’s a kite woman/High flyin’ woman/Kite woman’s got you strung out/Somewhere down the line/But you don’t mind.” If it was a term paper, Souther would have found “C+ –needs more work” scrawled across the top.

The only Frey-Souther co-write on the album, “Bring Back Funky Women,” is a not very successful “get down, mama” number, and closes the first LP side with a damp squib. The second side begins with “Star-Spangled Bus,” a lackluster Souther quasi-gospel number that Knechtel tries to sell with his spirited piano and Souther pushes vocally with a detectable lack of sincerity with each “hallelujah.” Osborne and Gordon are once again superb, and Cooder and Burton have their moments too.

The first really slow song, “Mister Mister,” is next, and Souther again flubs the songcraft, poorly constructing a “message” of mostly clichés with questionable grammar: “You say men are born in anger/To be cruel is to be strong/Wouldn’t it make you happy/To open your eyes and find you wrong?” Singing in a John Denver-type “pure” voice doesn’t help.

“Don’t Talk Now” is the only non-original on the LP, and it’s by James Taylor, who included it on his debut Apple album in 1968. Frey and Souther correctly intuited it could benefit from their Everlys-by-way-of-Flying Burrito Bros. treatment. Replacing the original’s harpsichord with Cooder’s slide guitar and reconfiguring the backing vocals, Longbranch Pennywhistle hit a home run. Too bad Amos didn’t have the infrastructure to release “Don’t Talk Now” as a single and see if AM radio would get on board.

At five minutes, “Never Have Enough” is the album’s longest track, and is an embarrassing Latin-tinged “humorous” number that sounds in structure uncomfortably close to the Archies’ “Sugar, Sugar,” which was a #1 smash around the time Longbranch Pennywhistle was issued. When Universal Music released the Glenn Frey boxed set Above the Clouds in 2018, the entire Longbranch Pennywhistle album was included on CD for the first time, but two minutes of “Never Have Enough”’s repetitive ending were lopped off, mercifully.

Longbranch Pennywhistle isn’t completely a lost opportunity. The sparks of genius here and there in the songwriting, and especially in the deft singing and instrumental arrangements, blossomed once Frey and Souther got more experience, found the right setting for their talents and collaborated with other sympathetic musicians, especially Don Henley, the drummer of another unsuccessful Amos Records signing, Shiloh. It wouldn’t be too many years before they could not only purchase their own drinks at the Troubadour bar but could also buy a round for the house every night of the week—or buy the whole joint if Weston wanted to sell.

[The album is available here. Many of the recordings are included on this 2018 Frey collection. Souther’s You’re Only Lonely has a 2024 edition.]

Related: Our Album Rewind of the Souther Hillman Furay Band’s debut album

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationGreat to get this; trust me it’s a keeper

I listened to the songs and agree, it’s a keeper.