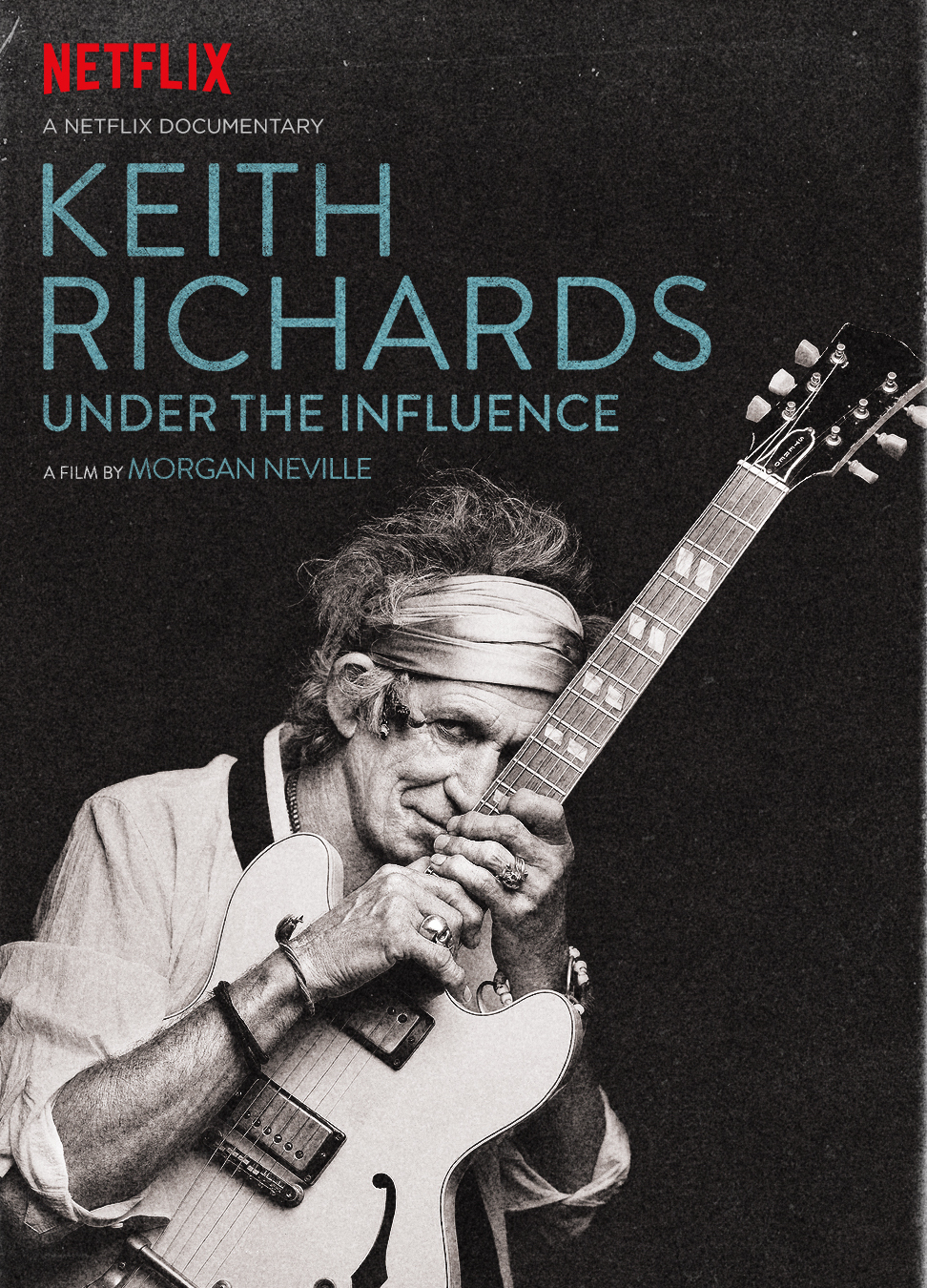

We first see the man ranging around his Weston, CT property to the tune of some classical music, an old man, it seems from behind, ruminating on the past. “Life’s a funny thing,” he says in the voice-over for Keith Richards: Under the Influence, “I always thought as a young man that 30 was about it, it would be horrible to go past that mark… until I got to 31. Life’s a funny thing. You’re not grown up until the day they put you six feet under.” The guest of honor was born on December 18, 1943.

We first see the man ranging around his Weston, CT property to the tune of some classical music, an old man, it seems from behind, ruminating on the past. “Life’s a funny thing,” he says in the voice-over for Keith Richards: Under the Influence, “I always thought as a young man that 30 was about it, it would be horrible to go past that mark… until I got to 31. Life’s a funny thing. You’re not grown up until the day they put you six feet under.” The guest of honor was born on December 18, 1943.

Then the camera swoops up to the gables of his house and the classical music resounds with a cymbal-crash of finality. “Music is the center of everything. It binds people together through the centuries.” Cut to: a very kid-in-the-candy-store Keith Richards in his parlor with a stack of old record albums. He puts a Little Walter Chess side on the turntable – Walter, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon, Sonny Boy Williamson, all of these guys made records with Muddy Waters at Chess Records in Chicago – and we hear the lonesome raspy blues that is gospel to this man. He is transfixed, not an old man at all but a teenager. Keith Richards is in church.

For the next hour and twenty we ride along with him on a fascinating travelogue that starts and ends with the blues. Yes, we’ve heard the stories before, how Mick and Keith met on a suburban commuter train and bonded over their collection of these same rare blues LPs from Chicago and the deep South, how they took what they heard on those records and brought them back to the music’s country of origin, and even how they went to Chess Records to record and discovered their idol Muddy Waters on a ladder with a paintbrush in his hand. But to hear them again, told in conversation, with flashbacks of documentary footage bouncing around from the past to the present, in which Keith is making an album, that is truly a good thing, and an enjoyable one at that.

That story about Muddy, for instance. Waters was a god to these guys (“He took me under his wing. I am so honored by that”). They studied his music and here they are in the place where it was made and they get to meet him and the great man is all humble – dignified and stately, even in this rare moment when he is not wearing a suit – and telling them he appreciates that they have brought the blues to the masses. “Thank you for what you guys have been doing,” he tells them.

The 2015 Netflix documentary is filled with these anecdotes, many of them about blues encounters but just as many redolent of the Rolling Stones “tales of the road” that I for one can never get enough of. The T.A.M.I. Show, the newsreel footage of screaming kids and R&B stars, the infamous Dean Martin Show on which the aging Rat Packer deadpans the audience with a smirk after they exit the stage, and the Brit pop show where the announcer dutifully introduces Howlin Wolf to the gum-chewing crowd and he kills it, really kills it – all of these moments in rock history we’ve seen before but not quite from this perspective.

The director’s POV keeps coming back to Keith in the studio making his solo record, Crosseyed Heart (read our review here): talking with Steve Jordan, who co-produced it, tipping the hat to Waddy Wachtel, Ivan Neville, Bernard Fowler, Sarah Dash and Bobby Keys (no longer with us but his presence is felt in the flashbacks), who played on it. And then it bounces around to some of the favored players in Keith’s musical life.

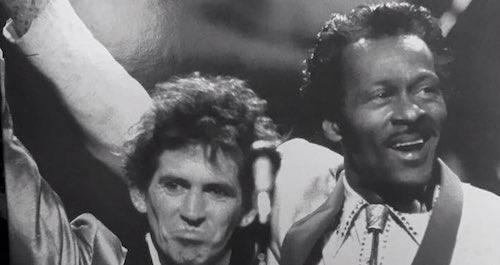

You get the apropos homage to Gram Parsons around the period of their collaboration on “Wild Horses,” complete with a section on those Nudie suits and the crazy man who tailored them. “I was very much drawn to him and he was a big influence,” Keith says of Parsons. Cut to a cool photo of the young debauchees in flagrante delicto. There is that Saturday Night Live performance of the X-Pensive Winos introduced by Tom Hanks, with a younger version of pretty much the same crew who are making this record with him now. And of course, Keith’s near-pugilistic encounter with another one of his father figures, Chuck Berry, in the Taylor Hackford-directed Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll from 1987.

You get the apropos homage to Gram Parsons around the period of their collaboration on “Wild Horses,” complete with a section on those Nudie suits and the crazy man who tailored them. “I was very much drawn to him and he was a big influence,” Keith says of Parsons. Cut to a cool photo of the young debauchees in flagrante delicto. There is that Saturday Night Live performance of the X-Pensive Winos introduced by Tom Hanks, with a younger version of pretty much the same crew who are making this record with him now. And of course, Keith’s near-pugilistic encounter with another one of his father figures, Chuck Berry, in the Taylor Hackford-directed Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll from 1987.

But for me, the coolest piece of loving documentary here is the set-piece from “Street Fighting Man,” fascinating footage about the songwriting process. We see Keith and Charlie Watts in the studio, just an acoustic guitar and a little drum kit between them. “Charlie and I were just fiddling about. There’s not an electric guitar on that one. It’s all overloaded acoustics. I used a little cassette machine as a pickup.” As if on cue, in real time, Keith’s guitar handler and right-hand man Pierre de Beauport comes in with the actual tape machine in question, places it reverently on the table and Keith proceeds with a discourse on lo-fi electronics. And then the rock ‘n’ roll professor – seriously, that is his persona in this film – gives out with an academic disquisition on the dynamics of songwriting. Forget about the trivia-bait factoid that “Street Fighting Man” was the Stones’ version of Unplugged. Here is the guy who is known for the debauchery, the booze-and-bawd histrionics of Cocksucker Blues, the noble rhythm player, showing up for his legacy as the other half of the Glimmer Twins. In no uncertain terms, and yet with the wisdom and restraint that comes with age, Keith lets us know that, “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking,” “Wild Horses” and “Under My Thumb” among them – he actually wrote all those songs, and crafted them in a very artisanal way.

The level of intimacy and knowledge that was created by director Morgan Neville (20 Feet From Stardom) could only have been achieved by someone who had Richards’ trust – and his back – and that is why he was invited to the party by Mindless Records in the first place. It didn’t hurt that he had worked with Richards before, on Crossfire Hurricane, the 2012 HBO documentary about the early years of the Stones up till 1981, and 2003’s Muddy Waters: Can’t Be Satisfied, which he co-directed with Robert Gordon.

It is probably that connection which colors Under The Influence‘s deep-blues emphasis and I think it truly defines its subject and frames him in the roots music that transformed the Stones, the so-called British Invasion and probably rock ‘n’ roll itself going back to Elvis and Carl Perkins. And while Richards is quick to point out and illustrate the country side of that equation in his erudite ramblings, this story begins with the blues and goes out on a 12-bar coda as well.

The caravan – essentially Keith in various cars and limos, riding around to signposts from his past and hounded for autographs everywhere that is not inside the womb of the studio – travels to Chicago, where Keith stops at Chess (flashbacks of Buddy Guy rockin’ it back in the day interwoven with footage of him and Keith shooting pool. Buddy says, “I used to go to Chess and turned up my amplifier like these guys,” Keith sinks an eight-ball in the corner pocket); a visit to the now-decrepit Chicago landmark home of Muddy Waters (“Willie Dixon brought me here… I don’t remember leaving. Somehow, when I woke up I was in Howlin’ Wolf’s house”); and the greatest piece of Stones iconography I ever saw on YouTube, footage from Chicago’s Checkerboard Lounge in 1981: “Mannish Boy,” in which the Muddy-Keith-Mick dynamic was laid bare and frozen in time (and, thanks to an enterprising entity in the Stones organization, available in an official release of the entire performance restored from the original footage and with sound mixed and mastered by Bob Clearmountain) because everyone at the gig was loaded and in good spirits. That set was November 22, 1981, when the Stones arrived in Chicago prior to playing three nights at the Rosemont Horizon. Along with Keith and Mick, Ronnie Wood and Ian Stewart were on stage, and later Buddy Guy.

In the end, Neville wraps it up neatly with a question about the old blues guys that started Keith up:

“When you were young it seems like you wanted to be one of those guys. Today, maybe you are one of those guys?”

The director metaphorically answers his own question by showing Keith’s melancholy version of Leadbelly’s “Goodnight Irene.” And that’s a wrap.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.