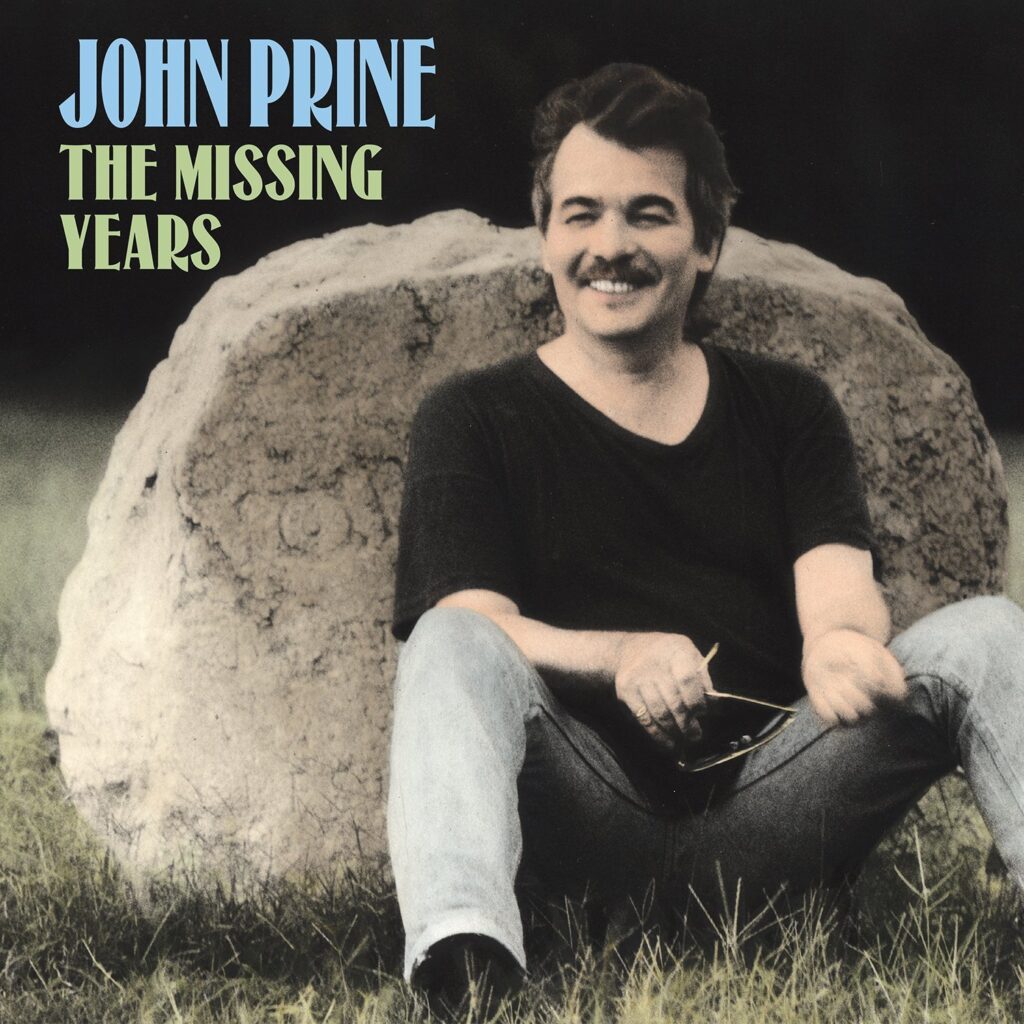

When it came time to record his tenth album, The Missing Years, in 1991, John Prine was ready to shake things up. Prine’s previous LP, German Afternoons, on Oh Boy, the label he co-owned with his longtime manager Al Bunetta, had appeared five years before, and received a Grammy nomination in the Contemporary Folk category. With nearly non-stop touring from his base in Nashville, Prine could gauge the success of new songs through his favored songwriter-to-live-audience method.

When it came time to record his tenth album, The Missing Years, in 1991, John Prine was ready to shake things up. Prine’s previous LP, German Afternoons, on Oh Boy, the label he co-owned with his longtime manager Al Bunetta, had appeared five years before, and received a Grammy nomination in the Contemporary Folk category. With nearly non-stop touring from his base in Nashville, Prine could gauge the success of new songs through his favored songwriter-to-live-audience method.

Long considered one of the best lyricists and performers in the country-folk genre, Prine nonetheless always downplayed his talent. In 1993 he told the journalist David Fricke, “The funny thing is, I consider myself to be one of the most undisciplined people in the world, let alone a songwriter. Totally irresponsible. I’d leave a song in a hot second for a hot dog…but, you know, it’s in that same attention span where you dream up some of the best stuff.”

Reaching out to Howie Epstein, the bass-player for Tom Petty’s Heartbreakers, Prine arranged to record most of the new album in Epstein’s house in Los Angeles, with a large cast of musicians coming and going for nine months, longer than it’d ever taken Prine to record an album before. “Howie has one of those houses [in the Hollywood Hills] that looks like it’s going to fall off the cliff,” Prine told Robert Baird of the Phoenix New Times after The Missing Years was released in autumn 1991. “But it was great. All we paid for was the musicians, the tape and the engineer. I recorded most of it in a hallway. I mean a hallway—we’re talkin’ three and a half feet wide.”

Epstein had just recorded his girlfriend Carlene Carter’s album I Fell In Love, and could call on many of the same players, including his Heartbreakers bandmates Benmont Tench (keyboards, bass) and Mike Campbell (guitar, bass), and three celebrated multi-instrumentalists, John Jorgenson (guitar, bass, mandolin, dobro, woodwinds), Albert Lee (guitar, piano, mandolin) and David Lindley (anything with strings). As he told Baird, “Lindley, who I’ve known for years but never worked with, drove up in a van full of 18 instruments, unpacked and stayed for a week. If I’d have made this record in Nashville, I would have had to sit down and seriously plot it out with people like him.”

Prine told journalist John Tobler that as the sessions proceeded, and he rose to the songwriting and recording challenges Epstein laid down, he became more confident about the results, and “had no shame” about inviting friends to sing backing vocals, a group that eventually included Bruce Springsteen, Bonnie Raitt, Phil Everly and Tom Petty.

For The Missing Years songs, Prine continued to create cogent character studies, oddball love songs and satires of modern life. As he told writer Bruce Pollock, “A lot of stuff has come out of just writing a couple of pages and rambling on, going from one mood right into another. Then I put it away and if I wait long enough I pull it back out and the good lines stay there and the others just fall right off the page. You can’t tell the good lines from the bad lines right at first sometimes—it’s a matter of editing. In general I’d say it’s not subjects I’m trying to pinpoint, it’s different moods…I think I’m a better lyricist than melody writer, so I’m trying to balance out the two, because what I’m doing is writing songs, I’m not writing stories and I shouldn’t always let the story carry the thing.”

He told another writer he worked from what he called “pessimistic optimism…You admit everything that’s wrong in a situation so you can get a laugh out of it, or at least look at it from a better angle.”

Given the lyric content and the location of the recording sessions, it’s appropriate that “Picture Show” begins the 14-track album. Petty helps with a high harmony in the choruses, and Prine namechecks James Dean, John Garfield and Montgomery Clift in this rousing celebration of the movies as an attractor of those with “a large imagination.” In the black-and-white video made for the track, Prine visits the Griffith Observatory, where Rebel Without a Cause was filmed, and strolls down the Hollywood Walk of Fame. In a characteristic last-minute flip that remains somewhat opaque, Prine turns the last verse over to a Native American “in a wigwam/Sitting on a reservation/With a big black hole/In the belly of his soul/Waiting on an explanation.” An explanation for what? We are presented with a white man who “sits on his fat can/And takes pictures of the Navajo/Every time he clicks his Kodak pics/He steals a little bit of soul.” So the images on the big screen come with a price? That’s pessimistic optimism for you.

“All the Best” is about divorce, saying farewell with a side of acid: “I guess I wish you all the best/I wish you don’t do like I do/And ever fall in love with someone like you.” As Prine said, introducing the tune on Irish TV, “Country songs and country songwriters are a strange lot. Seems like some of the best country songs over the years have come from some of the sadder situations in life, like divorce. Having recently acquired my second divorce, about a month later the song truck pulled up and dumped a bunch of great songs on my lawn.”

Jay Dee Manness’ pedal steel guitar is blended with Phil Parlapiano’s accordion, Tench’s organ and Joe Romersa’s spot-on drumming. Prine’s vocal is wry in all the right places. In the lyrics he tries out several metaphors for lost love, including the brutal “I guess that love is like a Christmas card/You decorate a tree/You throw it in the yard/It decays and dies/And the snowmen melt.”

Another standout follows. “The Sins of Memphisto” was written near the end of the sessions, when Epstein threw out a couple songs and asked for new ones. “So I went and locked myself into a hotel room and went, ‘If he wants a song, he’ll get a song,’” Prine recalled later. “I tried to write one from as far in left field as I could…I’m convinced I was just working the whole song to get around to the punch line, ‘Exactly Odo, Quasimodo.’” A fun clip-clop rhythm is the base for another exquisite mix of acoustic guitar, mandolin, accordion and Mickey Raphael’s harmonica. Liz Byrnes, another of Bunetta’s clients, handles the harmony vocal.

“The Sins of Memphisto” (Prine was thinking of the Egyptian city Memphis but ended up coining a new name) contains a number of winning couplets, including “Sally used to play with her hula hoops/Now she tells her problems to therapy groups” and “Esmeralda and the hunchback of Notre Dame/They humped each other like they had no shame.”

The first dud on the album, “Everybody Wants to Feel Like You,” a co-write with Keith Sykes, relies on simple chords, a mediocre melody and some wordplay that doesn’t really work: “Everybody wants to be wanted/I mean I ain’t no scarecrow cop/I don’t need no transalazation/I don’t need no diddley bop.” The minimal accompaniment was recorded in Nashville. The following “It’s a Big Old Goofy World” is no great shakes melodically either, but the overall performance, Prine’s engaging, laid-back vocal and amusing lyrics make it a winner.

It consists of a series of observations of human folly and folk wisdom like “Kiss a little baby/Give the world a smile/If you take an inch/Give ’em back a mile,” which Prine gathered by talking to his friends and inserting one of his favorite adjectives, “goofy.” By the last verse, Prine is confessing he’s “sitting in a hotel/trying to write a song/My head is just as empty/As the day is long,” as Lindley plays an instrument called the harplex.

“I Want to Be With You Always” was a hit for Lefty Frizzell in 1951, and Prine/Epstein give the only non-original on the LP a big-band oomph, with Jorgenson’s woodwind section and Steve Fishell’s Dobro providing color.

“Daddy’s Little Pumpkin,” a fingerpicked blues in the style of Mississippi John Hurt, is by Prine and Pat McLaughlin, and closes out the first side of the original LP version.

The clever “Take a Look at My Heart,” Prine’s co-write with John Mellencamp, features Springsteen singing harmony. It’s the most rocking cut on the disc; Albert Lee’s pithy guitar lines are unmistakable. The narrator is warning off his ex-girlfriend’s new man by advising him, “You don’t know what you’re getting into/She’s gonna tear you apart/You’re going places I’ve been to/Take a look at my heart.”

Mike Campbell’s biting guitar starts “Great Rain,” a song he wrote in standard blues format with Prine. It sounds thoroughly infused with early-’70s Bob Dylan and the Band. After Prine’s final image (“Great rain, great rain/I thought I heard you calling my name/I was standing by the river/Talking to a young Mark Twain”), Tench launches an organ solo that listeners might wish didn’t fade after a terrific 30 seconds.

The tender “Way Back Then” is a kind of adult lullaby, with lyrics that range from cynicism to tenderness: “Baby’s sleeping/Brother is on the run/I am out undoing/All the good I’ve done.” The instrumental arrangement is once again gorgeous, with Lindley in pole position.

“Unlonely” was written with the English pop hitmaker Roger Cook, co-composer of “You’re Got Your Troubles,” “Long Cool Woman In a Black Dress” and “I’d Like to Teach The World To Sing.” Cook’s the only British songwriter in the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, and had already worked with Prine on “I Just Want to Dance With You” for the German Afternoons LP; it became a #1 hit for George Strait in 1998. “Unlonely” is beautifully played, and has Bonnie Raitt singing, but it has minimal impact in the context of The Missing Years.

“You Got Gold,” another Prine-Sykes song, is a peppy number with some Tex-Mex instrumental details, including Lindley on fiddle, an “El Paso”-style acoustic guitar that sounds like Jorgenson, and Parlapiano’s accordion one more time. Phil Everly is the guest vocalist.

The voice-and-guitar Nashville-recorded tune “Everything Is Cool,” is Prine’s melancholy set-up for the album’s last, and possibly best, track, the six-minute “Jesus the Missing Years.”

Starting as a talking blues, the final track fills in the story the Gospels don’t cover, in outrageous style. Jesus has a run-in with the police, cuts his hair, settles down with his Irish bride in Rome, becomes a songwriter, sees Rebel Without a Cause on his 13th birthday…until his appointment in Jerusalem. Who but Prine could imagine Jesus meeting “an old black man with a fishing rod/He said, ‘Whatcha gonna be when you grow up?’/Jesus said, ‘God’…/I’m a human corkscrew and all my wine is blood.”

As Prine told Baird, the flamboyant and blasphemous travels of Jesus might have been jump-started by his own state of mind: “Before I started The Missing Years, I made up my mind that if it didn’t come out, didn’t end up representing my music well, I was going to check into something else. My first plan was to go to Germany and take acting lessons so I could be in a Wim Wenders movie.”

The Missing Years, released on Sept. 24, 1991, went on to win Prine the first of his four Grammys. His reputation grew in the next decades, even as he fought off cancer twice, which damaged his voice in 1998 and his lungs in 2013. He died of the complications of Covid-19 on April 7, 2020, at the age of 73.

“In the end, people want the truth,” he once told the writer Holly Gleason. “The second you start second-guessing or writing ‘to’ them, you’re screwed. You can’t make ’em authentic. People think through marketing they can deliver what people want, but [people] know.”

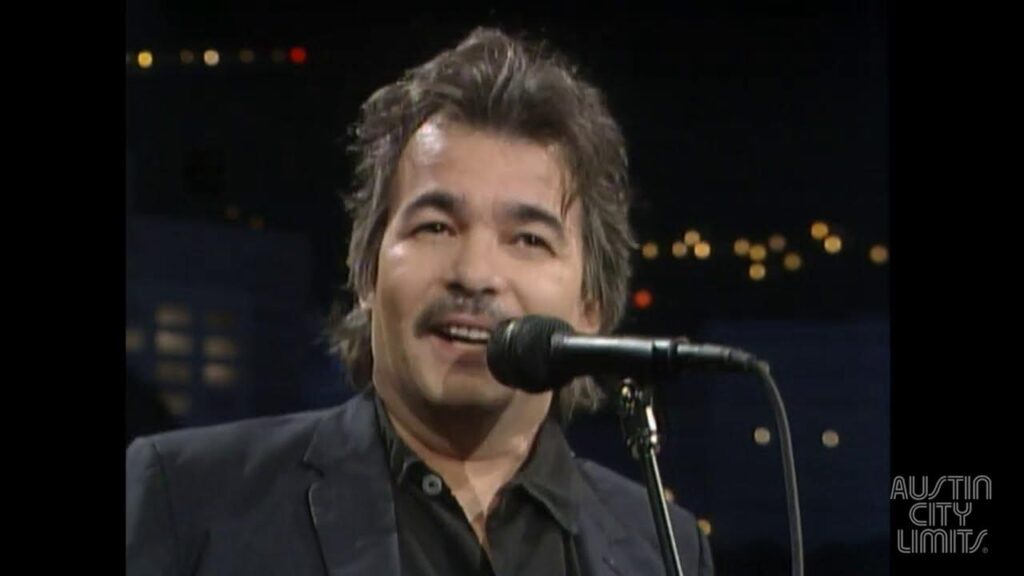

Watch Prine perform “Jesus the Missing years” on Austin City Limits in 1992

Related: John Prine’s 2018 intimate concert of stories and songs

The album, and other Prine works, are available to order in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationOne quibble: Everybody Wants to Feel Like You is no dud. It’s a beautifully simple rumination on being second fiddle in a relationship, with some typically great fingerpicking. (Is Mr. Leviton a musician?) An otherwise enjoyable tour of a fine old album that’s aged well.