On his third album, 1974’s Late for the Sky, Jackson Browne gauged the tension between the ’60s idealism of his youth and “the resignation that living brings” as he navigated adulthood, now tethered to a new family and an infant son. Between songs exploring the fault lines of relationships, Browne served glimpses of mortality and portents of apocalypse seen in “dark clouds gathering up ahead.”

On his third album, 1974’s Late for the Sky, Jackson Browne gauged the tension between the ’60s idealism of his youth and “the resignation that living brings” as he navigated adulthood, now tethered to a new family and an infant son. Between songs exploring the fault lines of relationships, Browne served glimpses of mortality and portents of apocalypse seen in “dark clouds gathering up ahead.”

On March 26, 1976, three weeks after he began working on his next album, a truly jolting darkness descended when his wife, Phyllis Major, was found dead from an overdose, leaving him a widower with a two-year-old son. Sessions were halted until May, when Browne returned to the project. Whether Browne’s embattled dreams of community and faith in family could survive such a waking nightmare seemed far from certain.

That he chose to open with “The Fuse” conveys resilience—it’s an anthem to survival, balancing “fear of living for nothing” against its credo of self-determination. “Through every dead and living thing, time runs like a fuse,” Browne insists, “and the fuse is burning,” carrying the song upward with his pledge to strive for “the higher ground” of social awareness.

A propulsive arrangement driven by Craig Doerge’s piano and David Lindley’s keening slide guitar is anchored by Russ Kunkel and Leland Sklar’s simmering interplay on drums and bass, establishing the album’s sonic design, with producer Jon Landau trading the warmer glow of Browne’s self-produced predecessors for harder, more polished edges.

For the prior album, Browne had relied on his touring band, but he harbored second thoughts after well-meaning peers asked whether he needed outside help. He was also frustrated that he “didn’t know how to make rock ’n’ roll happen” on uptempo tracks. Landau, then basking in the reflected glory of Bruce Springsteen’s career-defining Born to Run, offered reassuring credentials and enlisted a large cast of crack studio players. Browne himself would ultimately focus on vocals, leaving piano to the hired guns and only picking up a guitar for a single track.

That approach meshes powerfully on “Your Bright Baby Blues,” a pitch-black ballad powered by an A-list ensemble including drummer Jim Gordon, bassist Chuck Rainey, the E Street Band’s Roy Bittan on piano, and Little Feat’s Bill Payne on organ. The track’s real MVP is Feat co-founder Lowell George, with whom Browne had performed the song on a ’73-’74 winter tour co-headlining with Linda Ronstadt, reconfiguring it from a country-rock lament with a tougher R&B-veined sensibility.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Running on Empty

From the urgency of “The Fuse,” Browne slows to a near halt, “sitting down by the highway” as he watches others “riding just as fast as they can ride” on a journey the singer already knows to be futile once he’s concluded, “No matter how fast I run, I can never get away from me.” Pleading for salvation in a lover’s “sweet tenderness,” the song shifts to a bridge modeled on Sam Cooke’s classic “Bring It on Home to Me” featuring Browne and Lowell George in a call-and-response duet echoing Cooke’s and Lou Rawls’ on the 1962 original, but with a startling pivot from plea to withering putdown.

“Well, I can see it in your eyes

You’ve got those bright baby blues

You don’t see what you’ve got to gain

But you don’t like to lose

You watch yourself from the sidelines

Like your life is a game you don’t mind playing

To keep yourself amused

I don’t mean to be cruel, baby

But you’re looking confused.”

The volley from need to conflict reverses in a second confession of “love stirring in my soul” before an instrumental bridge anchored by Bittan’s and Payne’s keyboards and George’s mournful electric slide guitar, soaring above the band. In the hush that follows, Browne knits its themes of identity, dependency and addiction into its closing verses mingling surrender with deep need.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Browne’s debut

Following by far the grimmest song he had yet penned, Browne retreats with “Linda Paloma,” a delicate love song dressed in lacy Mexican acoustic mariachi filigree, before quickening the tempo for “Here Come Those Tears Again,” the album’s single featuring lyrics co-written with Nancy Farnsworth, his deceased wife’s mother. A medium tempo rocker, the song hews to more conventional tropes as lovers quarrel, trust is broken, and tears are shed before an angry but open-ended kiss-off.

Midway through the album, Browne turns to fatherhood and “The Only Child,” addressed to his son Ethan, whose third birthday would arrive along with The Pretender that November, offering tender counsel and the poignant need to “take good care of your mother.” Father then becomes child on “Daddy’s Tune.” Browne confronts his own daddy issues in a reconciliation over past tensions marred by an overripe horn section that suggests a little too much production polish.

If the more downbeat songs resonate with his real-life tragedy, Browne acknowledges his wife’s death directly only on the penultimate track, “Sleep’s Dark and Silent Gate.” On the edge of sleep, he contemplates the loss in the quiet declaration, “I found my love too late,” triggering agonizing remorse (“Never should have had to try so hard to make a love work out…”) and sorrow (“I don’t know what love has got to do with happiness”). Against David Campbell’s somber orchestration, Browne quotes “Your Bright Baby Blues”’ opening line as a descant before a heartbroken admission, “Oh God, this is some shape I’m in,” doubling its impact with its reference to his now motherless son.

That catharsis precedes the album’s bittersweet finale as Browne turns his gaze to his generation and a different kind of death, this one spiritual. “The Pretender” adopts the tone of earlier anthems including “For Everyman” and “Before the Deluge,” replacing their idealism with cynical fatalism in the title character “caught between the longing for love and the struggle for the legal tender.” As he details a quotidian existence, numbing himself in “paint by number dreams,” the singer offers an indictment for peers now content to dismiss “the changes we waited for love to bring” as “fitful dreams,” surrendering to the status quo.

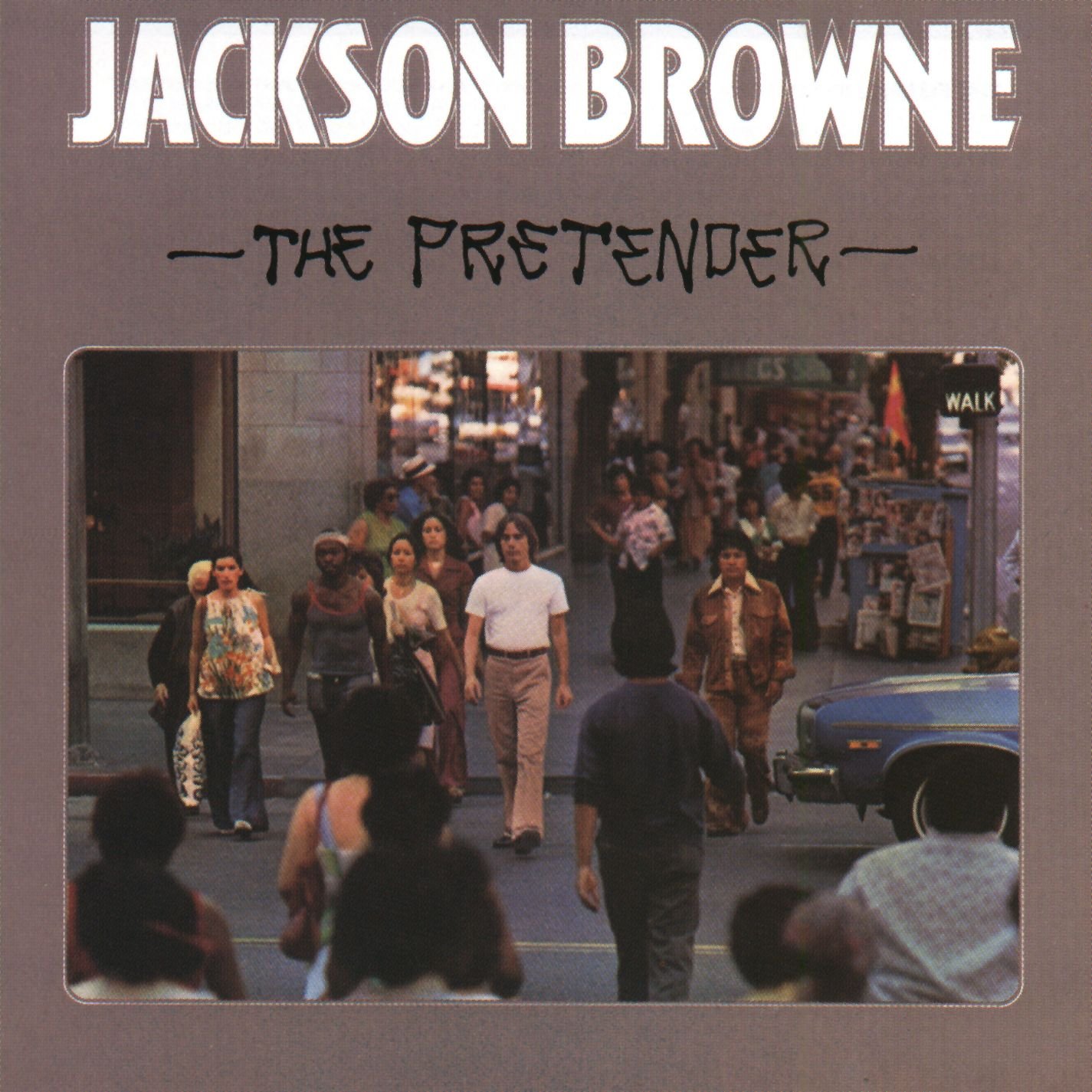

Campbell’s sweeping orchestral arrangement and Graham Nash’s and David Crosby’s vocal harmonies decorate a tableau populated with neighbors and passers-by, just as the cover art captures Browne crossing a crowded intersection. A coda turns its title into a challenge—“are you there for the pretender”—that reveals the artist’s unchanged core belief, but The Pretender projects a more sinister and less forgiving world than Browne’s earlier works, a sensibility that overlaps with two other significant Asylum releases that year, the Eagles’ Hotel California and Warren Zevon’s self-titled label debut, co-produced by Browne.

The Pretender, released in mid-November 1976, was a commercial triumph, reaching the top 5 of the chart. It eventually netted triple platinum sales, suggesting its downbeat world view resonated rather than repelled listeners. Its harder edges and rock muscle would find even greater success with Browne’s ambitious live album, Running on Empty, but Jackson Browne would keep his “fitful dreams of some greater awakening” alive in the decades to come.

Bonus Video: Watch Browne sing “The Pretender” with Crosby, Stills and Nash at Madison Square Garden in 2009

Browne’s extensive recorded legacy is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNot a fan of the politics, but man, I couldn’t begin to count the number of times I spun “The Pretender”, and Jackson Browne’s preceding albums, as a college D.J., as well as in my dorm room.

Then, to follow- up with “Running On Empty”, Browne proved he had a creative streak, and cerebral lyrics that was unstoppable for almost a decade.

Great article and a great era for music.

Agree, one of the best wordsmiths ever, except for the politics.

Browne is a quintessential poet of our time. “Late for the sky” solidified him as such for me, especially after listening to “Farther On” that first time. What a journey! It is no wonder that David Crosby described a perfect evening is hanging out with Jackson and a piano. I’d love to meet him to thank him for his gift and get some guitar tips at the same time.

Excellent article about a great album.

Nearly 50 years later I still think about the phenomenal lyrics from “The Pretender”.

Especially:

“I’m going to find myself a girl

Who can show me what laughter means

And we’ll fill in the missing colors

In each other’s paint-by-number dreams”

Just wow.