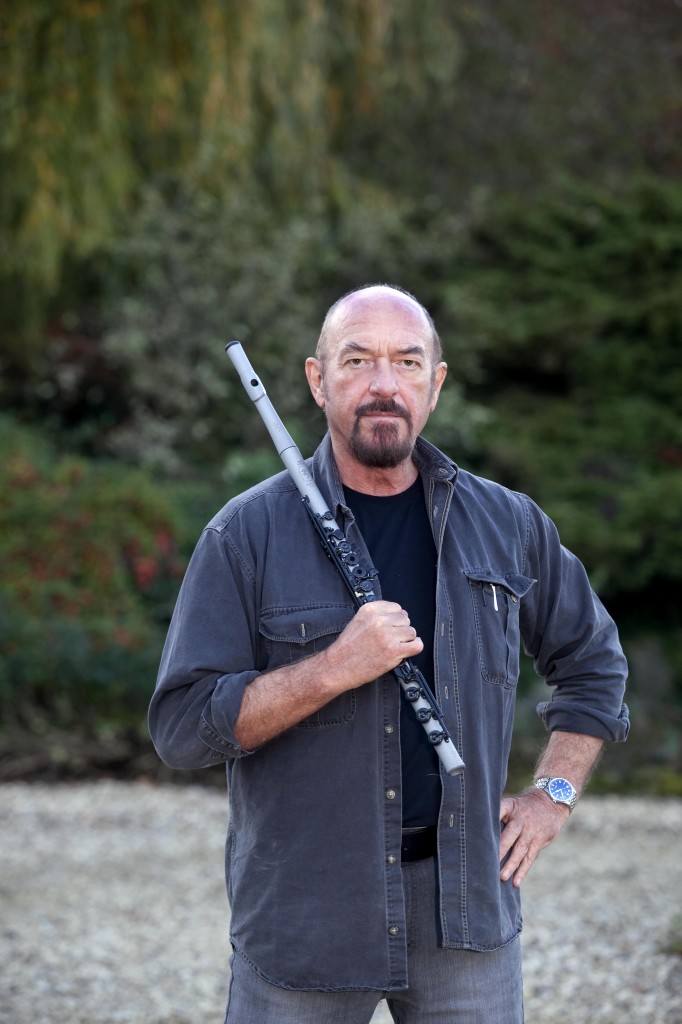

Photo by Martyn Goddard

This interview first appeared on Best Classic Bands in 2015.

One of my favorite opening song lines ever comes from Ian Anderson. The singer-songwriter who led Jethro Tull, begins the nearly 44-minute opus Thick as a Brick with a lilting, “Really don’t mind if you sit this one out….“

It’s a literal invitation to the listener to take a pass. How audacious!

“It was a kind of a brave and potentially rather insulting thing to have done to an audience,” muses Anderson, 43 years after the fact, on the phone from England, “but [Thick as a Brick] really was sort of a take-it-or-leave-it sort of affair. And people didn’t overtly take offense so it worked out OK.”

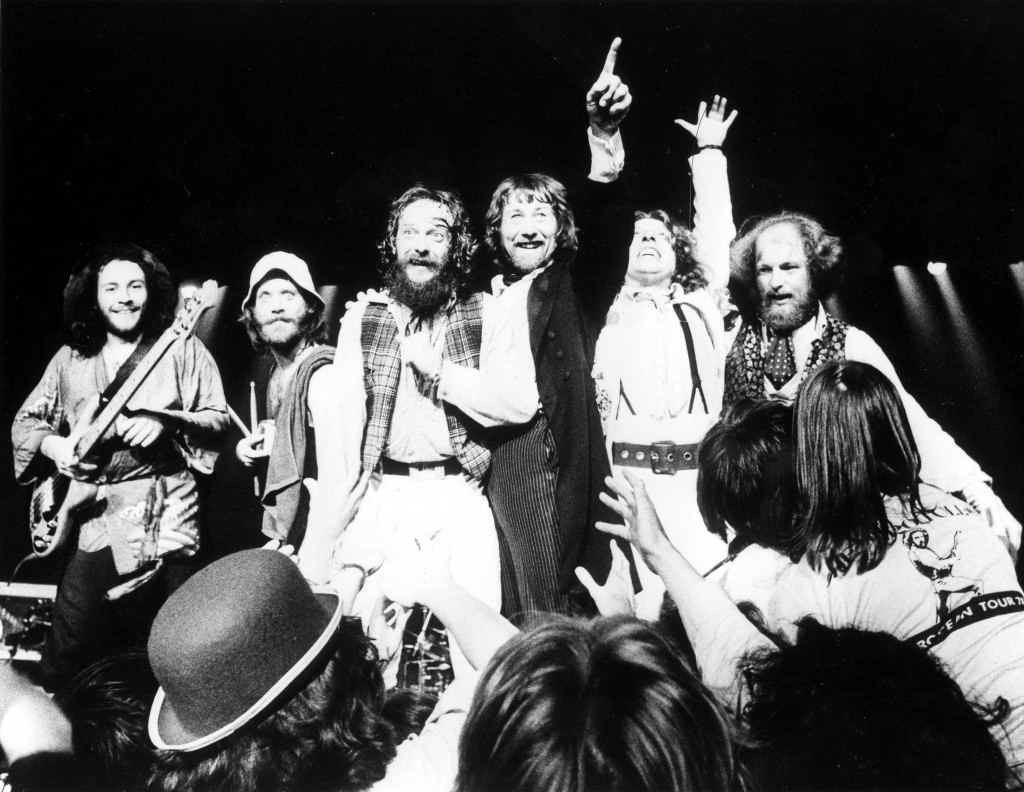

That it did. The follow-up to the band’s breakthrough Aqualung album hit #1 and solidified Tull’s position as this curious, brainy prog/folk-rock outfit that found a huge audience in America – on FM radio, in hockey barns and, for a while, even on AM radio. Led by a flautist who often balanced on one leg, wore a codpiece onstage, and sang songs as markedly English as anything the Kinks or Fairport Convention did.

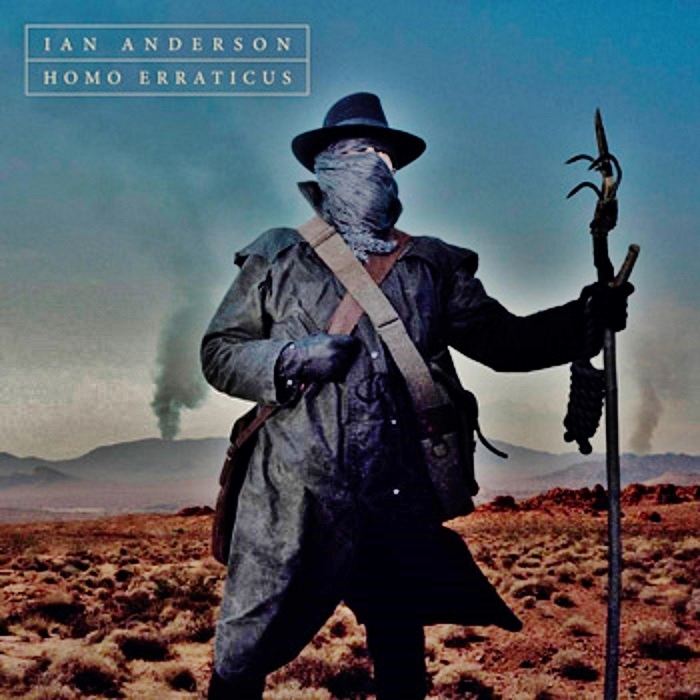

Jethro Tull – formed in 1968 and eventually encompassing 27 musicians over the decades – never lacked for ambition. That remains true for Anderson today, who has dropped the Tull band name in favor of his own for his latest concept album, the double-disc Homo Erraticus. He has gone solo for five previous studio albums, beginning with 1983’s Walk into Light. Jethro Tull also released seven studio albums over that period.

Why Ian Anderson and not Jethro Tull?

“I’m lucky to have my name known before I die and not just be somehow a figurehead under that Jethro Tull name,” Anderson says. “But the name Jethro Tull figures in most of the concerts I play, whenever I’m playing Jethro Tull repertoire which is most of the time.”

And so, the tour was called “Jethro Tull by Ian Anderson.” Anderson explains: “I’m the guy that wrote the songs, the lyrics, the music, produced the records and stood in the front and played guitar and flute and a few other things, so in my final dotage it’s kind of nice to think you might know my name. What it says on my passport; it doesn’t say Jethro Tull.”

When the band formed, Anderson had a vague idea of who the real Jethro Tull was. The band’s agent, a history major, chose the moniker, saluting the 18th century agriculturalist. “I’d always avoided doing [research] in the past,” says Anderson, “not wanting to know too much about him, through the kind of embarrassment, I suppose, of having hijacked his name.”

But then there was a drive Anderson and his wife were making through Northern Italy last year. He took in the rural farmland, thought about how crops were grown, “just paying attention to the agricultural methods of that region.”

“It just passed through my mind,” he says. “’I wonder what old Jethro Tull would have made of this? Would he have been interested in the kind of agriculture that was practiced elsewhere in Europe?’ And since I was a passenger in a car and had an internet connection via my phone I looked up ‘Jethro Tull the historical character’ and read a little bit about his life story.

“I found that indeed Jethro Tull had visited France and Italy to study the agriculture there and he did learn and incorporate some of those ideas into his treatise on agricultural improvements called Horse-hoeing Husbandry,” Anderson continues, of Tull’s 1762 book.

Anderson, born Aug. 10, 1947, found there were connections in Tull’s personal life, too, and they resonated. “When I read them I immediately conjured up songs I’d written in the last 40-odd years,” he says, “and suddenly I had about 20 songs I could make a list of that seemed, in some way, to be quite apt in touching upon a certain part of his life and times.”

Which would also double as: “A means of doing a ‘Best Of’ Jethro Tull, set to a narrative.” Let’s face it: No matter what Anderson has going on his head, whatever the linkage, there are classic songs fans want – nay, need – to hear.

If you’re a new Best Classic Bands reader, we’d be grateful if you would Like our Facebook page and/or bookmark our Home page.

Anderson had the idea to pluck aspects of Tull’s life for the concept tour, but did not want this Tull to be living in the past. “I moved it into the present day and near future,” he says, “so I could touch upon the challenges facing agriculture and food production worldwide in the years to come in the face of climate change and the limited resources we will be facing as certain areas become very difficult to produce food in.”

That became the rough framework of “Jethro Tull: The Rock Opera,” though I can’t say when I saw the show in Boston I would have gleaned much of that had I not spoken with its creator prior to it. It’s a multimedia performance featuring Anderson plus four live musicians, and three backing singers that Anderson says “live in a suitcase.”

“You have to bear in mind,” says Anderson, “my special guests are virtual guests who are on a big screen behind me travel in two pieces of check-in luggage in the form of two video servers that have all their parts and that we plug in. My special guests are with me but I don’t have to buy them dinner or a hotel room. They do, in fact, get paid for repeat performances.”

About 30 percent of the show uses prerecorded vocals from the singer-actors, mainly young female singer-violinist Unnur Birna Björnsdóttir and young male singer Ryan O’Donnell. An older singer, David Goodier, is also in the mix. (Goodier was the bassist for latter-day Tull and is mostly for Anderson solo, but was sitting out this tour.) They sing separately or duet with a live Anderson.

“Frankly,” Anderson says, “it’s kind of more fun having these characters behind me, 20-feet tall, rather than just little people on the stage. It’s nice having the big bright imagery that we can make part of the overall package.”

“Frankly,” Anderson says, “it’s kind of more fun having these characters behind me, 20-feet tall, rather than just little people on the stage. It’s nice having the big bright imagery that we can make part of the overall package.”

They played five tunes from Homo Erraticus: “Prosperous Pasture,” “Fruits Of Frankenfield,” “And The World Feeds Me,” “Stick, Twist, Bust” and “The Turnstile Gate.” And, of course, classics like “Heavy Horses,” which starts off the two-act show, followed quickly by “Wind-Up” and “Aqualung.” And others such as “Farm On The Freeway,” “Songs From The Wood,” “Living In The Past,” “A New Day Yesterday” and “The Witch’s Promise.”

Some of these are rewritten slightly, with the actor-singers onscreen taking parts. It comes to a roaring climax with “Locomotive Breath’ – yes, there’s an engine on the big video screen and that chunka-chunka guitar riff played by guitarist Florian Opahle. It was the point where the audience stood as one.

“The poor old Neanderthals got overtaken and came to end between 30 and 50,000 years ago, although in some circumstances they had bred with Homo sapiens,” he says, “so we’re fertile offspring of that conjoining. Indeed, I myself discovered – and I was really pleased – to find out I was 2.4 percent Neanderthal until I found out to my dismay that the European average is actually 2.5 percent. Throughout Europe it varies between one and four percent. Only in the last five years has this been known that there was literal cross fertilization between these two species. It made some people a little uncomfortable because there is a different DNA mix between people of different ethnic backgrounds, and some people get a  little twitchy about it. We’re not all the same; we’re all mixtures of species and not just Neanderthals and Sapiens.”

little twitchy about it. We’re not all the same; we’re all mixtures of species and not just Neanderthals and Sapiens.”

How do the songs played live from it dovetail into “The Rock Opera”? “It doesn’t have anything to do with it whatsoever,” Anderson admits, “although I suppose there are some little crossover elements in terms of my lyric writing. But it’s a separate issue. [The theme] is Homo Erraticus, a separate species, the wandering man, out of Africa looking for a better life and someone’s head to stamp on in order to get it.”

Is it exhausting to be Ian Anderson? Asked about his ambition – both when he was young and now – Anderson says it depends on the definition.

“I think as you get older you have more calm about what you do – you’re not ambitious perhaps in a ruthless way – but [when you’re young] certainly that would have been necessary to be a little bit ruthless and driven. Sometimes not in an entirely pleasant way because when you are trying to succeed in a very difficult and quite competitive marketplace. When new music was being born in the ‘60s, you had to be driven to survive the disappointments and literally the hunger and cold. It was pretty miserable for a few months trying to become a professional musician. Luckily, after a few months we began to be noticed and picked up a bit of a following and it developed fairly quickly after that. But for a few months, I was not far from despair and tears on occasions.”

Tull vs. Zappa & the Rock Hall

So, with all the history, over 60 million albums sold worldwide, does Jethro Tull belong in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame? The argument has been passionately made, but Anderson is not one to make it.

“If your music stylistically isn’t very American, then I don’t think you necessarily belong in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame,” Anderson says, “so I’m perfectly happy to sit out there on the periphery looking in. Am I worried about my not being – or Jethro Tull as a band entity – inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame? Not at all. I don’t think I should be there. It’s a very American institution so I think it should be there first and foremost to identity and to celebrate great American music.”

And to wit, until recently, Hall of Fame voters have not been terribly welcoming of the English wave of ‘70s prog-rockers. “Part of that also has to do with the position of Rolling Stone and the background of all of that,” says Anderson. “People like Frank Zappa were rather disdainful of the British invasion; they felt somehow threatened by it, and Zappa spoke rather badly of Jethro Tull. The memories I have were quite personally upsetting because I was a huge Frank Zappa fan. But he badmouthed us a couple of times publicly and that was a bit hard to take.

“Strangely, before he died, he started reaching out to people. I got a message passed to me that Frank wanted me to call him, giving me his home telephone number. I deeply regret I didn’t have the nerve to let the phone ring and have someone pick it up. I called him three times and hung up, being terrified, because I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t let the phone ring and speak to Frank. How do you deal with a guy that you’ve carried with you for a couple of decades the belief that he really didn’t like you and suddenly he wants to call you when he’s on his deathbed. Whatever it was he wanted to talk about I have no idea and never will now.”

One would tend to think he wanted to make amend. But I suggest to Anderson, Zappa being Zappa, that maybe he wanted to say you still suck.

Anderson laughs. “Yeah, that’s it. That might have been the outcome: I just wanted to tell it to your face before I fuck off.”

When Anderson tours, tickets are available here and here.

And here’s Anderson in 2022 talking about the 50th anniversary release of Thick as a Brick.

View this post on Instagram

Related: Our Album Rewind of 1972’s Thick as a Brick

- Interview: Ringo Starr’s Drum Beat Can’t Be Beat - 07/06/2025

- 10 Songs That Defined New Wave Music - 07/01/2025

- Mark Farner Interview: Grand Funk Railroad’s Legacy - 06/05/2025

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationGreat article Jim ! A favorite of mine…got to meet him with Oedipus …Such a talent…and fantastic , great last sentence to your article…best JG

An interesting man, and he/they certainly put on some great shows back in the day.

I’ve seen Tull a few times, but in the summer of 76, he played an outdoor show at Colt Park in Hartford, CT. J. Geils Band opened. They had cameras projecting onto a big screen behind the stage, which wasn’t the norm back then. There was a cutout surrounding the screen to make it look like a big TV set. He called it “Tullavision”. Loved every minute of it. Rock on Ian!