Bob Dylan’s ‘John Wesley Harding’: A Different Kind of Dylan

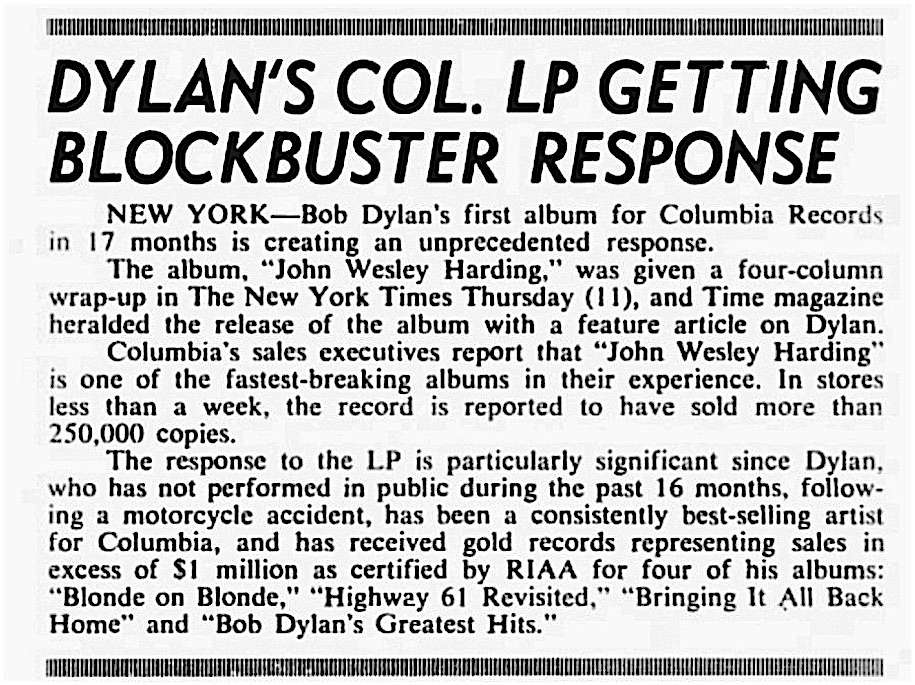

by Harvey Kubernik On December 27, 1967, Columbia Records released the Bob Johnston-produced Bob Dylan long-player John Wesley Harding. By January ’68 it was one of the most tracked albums on countless FM radio stations in America and all over the world. It was Dylan’s eighth studio album. During 1968, it eventually reached #2 on the U.S. record charts and a #1 slot in the U.K. charts.

On December 27, 1967, Columbia Records released the Bob Johnston-produced Bob Dylan long-player John Wesley Harding. By January ’68 it was one of the most tracked albums on countless FM radio stations in America and all over the world. It was Dylan’s eighth studio album. During 1968, it eventually reached #2 on the U.S. record charts and a #1 slot in the U.K. charts.

Author Clinton Heylin, in his book Bob Dylan: The Recording Sessions 1960-1994, describes John Wesley Harding as “Dylan’s most perfectly executed album; that austerity (in sound and lyric) is, frankly, a key element. The fact that Dylan wrote John Wesley Harding self-consciously as ‘an album of songs’ in a month and a day, and recorded it in just three afternoons, gives the album a unity all its own.”

Author Richard Williams, who wrote the exceptional book Dylan: A Man Called Alias, emailed this writer in 2007:

“Eighteen months was a lifetime in the late ’60s, and John Wesley Harding ended the longest, loudest silence in the history of rock and roll. No one knew what Dylan was up to. No one knew the truth about his ‘retirement’: Were the unconfirmed rumors of a motorcycle crash simply a cover for the time needed to free himself from advanced chemical dependencies? ‘I Pity the Poor Immigrant,’ ‘I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine’ and ‘All Along the Watchtower’ forced us all into a radical reconsideration. The album was a blast of clean air—not just for us, but for Dylan, too. And it still sounds pristine.”

That same year, I interviewed writer/author/ and singer/songwriter Mick Farren on John Wesley Harding.

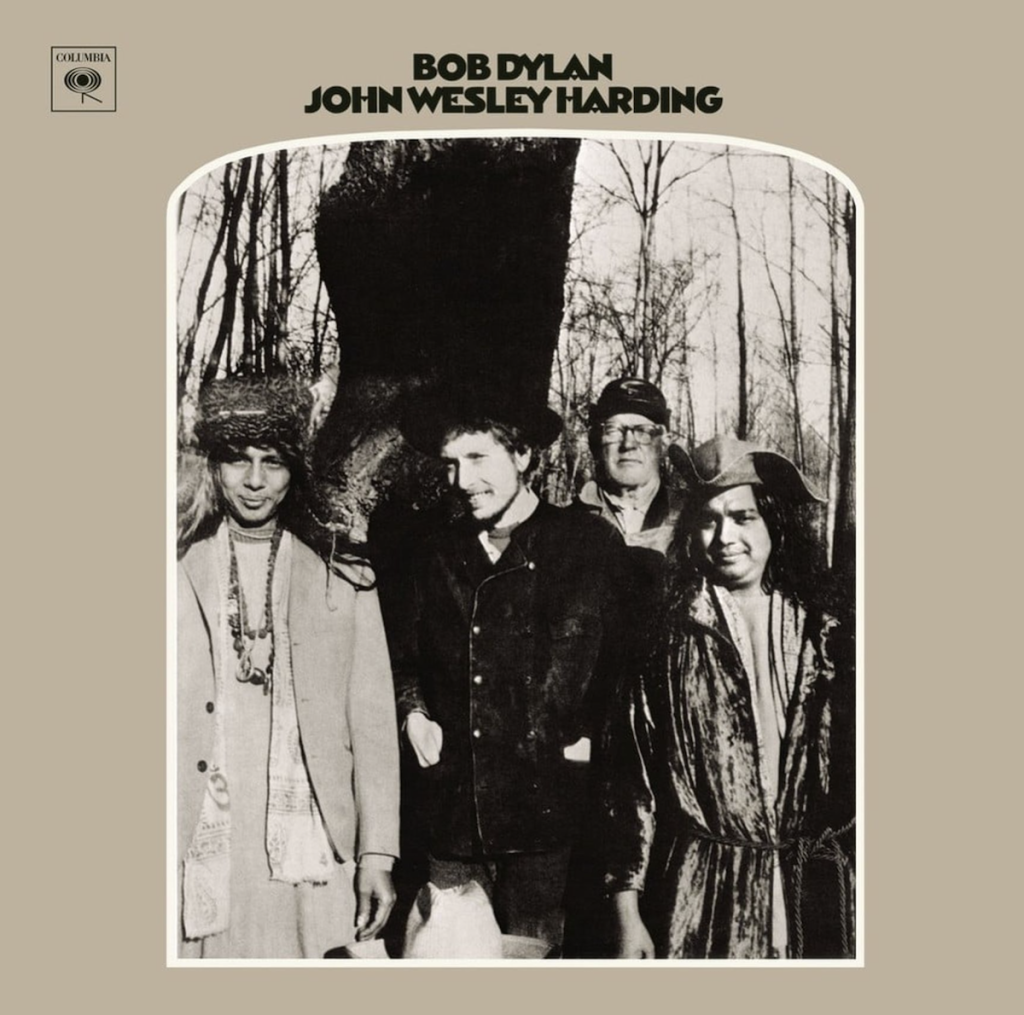

Mick Farren: The weight of anticipation that was loaded upon the release of John Wesley Harding was probably more than any artist should be expected to shoulder. How in hell was Dylan going follow something as monumental as Blonde on Blonde? And in the landscape that I inhabited, not only were fans, musicians, writers and rock critics asking the question. So were individuals who had regularly spent entire Sunday afternoons skulled to Neptune on the best obtainable acid listening to “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” over and over again, searching for some nebulous electric dharma of their own imagining. And when the answer turned out to be relaxed, controlled and even reserved, conflict broke out between those who just wanted more Blonde on Blonde and others who were frankly baffled and studied the cover photo for mystic clues.

“It’s hard to imagine all these years later,” muses lifelong Bobologist Gary Pig Gold, “the absolute shock it was ending 1967 on ‘I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight.’ I mean, after such a long wait since Blonde on Blonde, not to mention the full-on stereophonic circus with which various Beatles, Doors, Mothers, Monkees and even Stones had assaulted our hearing throughout the ensuing year, John Wesley Harding was in so many ways the cooling calm after the sonic storm. And not just musically, either: Even the simple, quasi-pastoral setting in sepia that greeted us with that album cover—Who are those three other guys with Bob? And Is that really the Beatles hidden in the tree bark?—scarcely prepared our overworked eyes and ears for the characteristic curveball Dylan again spun our way. Unless you were so prescient as to have heard Brian and his Boys’ equally unpsychedelic Wild Honey long-player just a few weeks before, JWH took only 38-and-a-half minutes to utterly rearrange one’s perceptions, and expectations, for all things rock and roll as the dreaded Year of ’68 dawned.

Related: Bob Johnston on Dylan’s Nashville sessions

Some backstory: Following Dylan’s motorcycle accident in July 1966, he was sidelined, at least in the public eye, for the better part of a year. Columbia Records staff producer Bob Johnston met up with Dylan at a Ramada Inn in Nashville, Tennessee, before working on John Wesley Harding together. In 2007, I interviewed Johnston, who has since passed away.

Bob Johnston: He played me some songs and asked, “What do you think about a bass, drum and guitar?” “I think it would be f**kin’ brilliant if you had a steel guitar.” “You know anybody?” “Yeah, Pete Drake.” He was workin’ with Chet [Atkins], so I got somebody to take his place and brought him over. Pete said, “Can I play some rock ’n’ roll?” And I told him, “That’s what you’re here for.” Charlie McCoy played a lot of instruments on that album. He played four, five or 20 instruments on every record. I would place glass around Dylan for recording He had a different vocal sound. I didn’t make his different vocal sound. He always had different sounds on. The rest of the world was doing albums as big as Blonde on Blonde—the more musicians they could get, the better it was. (But) we went in with four people…in the middle of a psychedelic world!

Multi-instrumentalist Charlie Daniels is heard on three Bob Dylan albums: Nashville Skyline, New Morning and Self-Portrait. During 2014, I interviewed him. [Daniels passed away in 2020.]

Multi-instrumentalist Charlie Daniels is heard on three Bob Dylan albums: Nashville Skyline, New Morning and Self-Portrait. During 2014, I interviewed him. [Daniels passed away in 2020.]

Charlie Daniels: When Bob Johnston moved to Nashville in 1966, he called me and said, “Why don’t you come to Nashville?” I always wanted to live there and packed up in 1967. He had just done Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde. All the good things that happened to me in the early days were because he was a cog in the wheel. In ‘67 and ’68, Bob [Johnston] produced the albums John Wesley Harding and Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison. Bob had gained credibility. He was also, at the same time, bringing Dylan and Leonard Cohen into town who had never lived here. There was skepticism about Bob [Johnston] coming to Nashville because he was taking the place of a legendary producer, Don Law, who was an institution in town. Here’s this guy Johnston from New York, who had been doing Simon and Garfunkel, Dylan and now Leonard Cohen, who were not really thought of as being country. But the first thing Bob did when he came to town was to do a number one song with [country singer] Marty Robbins. of Bonnie and Clyde, and of course, Johnny Cash’s live album at Folsom Prison. Hassles with long hairs, prejudice, racism, didn’t exist in our world. In the ’60s, everything was pretty much in the throes of a lot of upheaval. This was back in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s salad days, when he was going around, doing things that a lot of people didn’t understand. Cohen and Dylan were singers and songwriters. They wrote their songs; they weren’t coming in from a music publishing company. It was a lot different because there was no hurry. With Nashville Skyline [the followup to John Wesley Harding], we had about 15 sessions booked and probably only used half of them and it was over. Nashville Skyline and John Wesley Harding are two different records to me. The Nashville Skyline record was a departure for Dylan; it was just so different than anything I had heard him do. “What else you got, Bob? We got this one done.” And of course, Dylan is a big first-take guy. If you can get it on the first take that’s how he wants it. And I like that about him.

In 2007 I also spoke with Steven Van Zandt who helms Little Steven’s Underground Garage on the SiriusXM satellite radio network.

Steven Van Zandt: I play a lot of Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. We usually don’t play a lot of Bob’s things that classic rock stations are playing, like “Tangled Up In Blue.” I’ve programmed Rod Stewart and the Faces covering “The Wicked Messenger” from John Wesley Harding and Jimi Hendrix doing “All Along the Watchtower” from the same album. Dylan pretty much walked away from rock ’n’ roll for a minute, and started getting back to his roots and taking them to some other place, more the country and folk world where he came from. People didn’t know what to make of it at the time. It was a strange sort of new Bob Dylan that emerged after his July 1966 motorcycle accident. Jimi Hendrix did more to promote John Wesley Harding than anybody. It [Hendrix’s cover of “All Along the Watchtower”] was one of the most remarkable records ever made, of course. Jimi picked up on that from that unusual, and not very popular, Bob Dylan album and made everybody go back to it, thinking, “Maybe I missed something? Look what Jimi Hendrix did with it. Look what the Faces did with it.” It worked. It’s a terrific album but sort of subtle, compared to Blonde on Blonde.

John Wesley Harding is available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

Bonus Track: Listen to Jimi Hendrix’s classic cover of “All Along the Watchtower”

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI was in high school when JWH came out. I had a room mate who loved it and it rubbed off on me. JW Harding, Nashville Skyline and New Morning were kind of milestones to me. Great stuff.

Take the cover photo turn upside down and fix your look to the tree trunk at the now bottom of your JEH cover ! Who did you see?

Yes, allegedly the Beatles’ faces are there but it seems a bit of a stretch to us.

The Beatles appearance on the album cover was a response to Dylan being on the cover of Sgt Pepper’s. The other guys on the cover were around the house at the time. It was a perfect album cover.