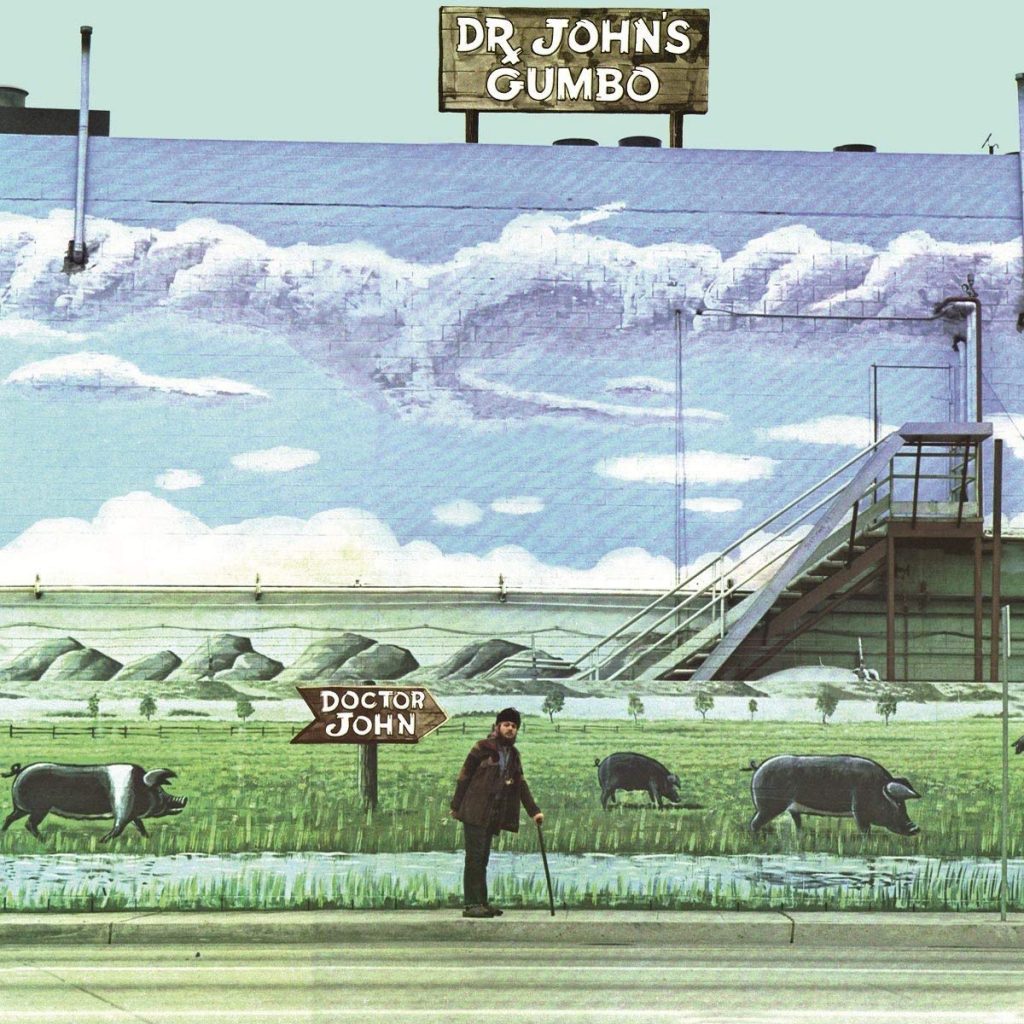

Gumbo is the sound of Dr. John hitting reset on a solo career by unmasking himself. Four previous ATCO studio albums had conjured a mystique that was part shaman, part trickster, weaving voodoo incantations and bayou patois through a slow boil of percussion, horns, keyboards, guitar and vocal chants that fused New Orleans’ multiethnic root styles with elements of rock and psychedelia. Onstage, he inhabited the role in elaborate headdresses, feathers, beads, face paint and glitter, fronting a live show noteworthy for its theatricality.

Gumbo is the sound of Dr. John hitting reset on a solo career by unmasking himself. Four previous ATCO studio albums had conjured a mystique that was part shaman, part trickster, weaving voodoo incantations and bayou patois through a slow boil of percussion, horns, keyboards, guitar and vocal chants that fused New Orleans’ multiethnic root styles with elements of rock and psychedelia. Onstage, he inhabited the role in elaborate headdresses, feathers, beads, face paint and glitter, fronting a live show noteworthy for its theatricality.

By 1971, however, dwindling sales and airplay clouded his hopes, compounded by clashes with his then-managers. When he vented his frustration to Atlantic Records executive Jerry Wexler during a session break, the veteran producer suggested a more organic escape route. “I was playing some old New Orleans songs,” he recalled in a 1973 interview with Rolling Stone’s Paul Gambaccini. “[Jerry]said, ‘Well, why don’t you cut an album of just what you’re doing, the old songs?’ [Two years] later when I was in a mess with management problems and everything, we got together for what came to be the Gumbo album, which all came from that night when we took a break from the session and was reminiscing.”

With that tipping point, Dr. John stripped away the greasepaint and glitter, reintroducing himself as Malcolm John Rebennack, a NOLA native who had grown up in the city’s Third Ward. Steeped in the music of local legends includingLouis Armstrong, King Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton, young Mac Rebennack had undergone an epiphany at 13 after hearing the music of Roy Byrd, better known as Professor Longhair, whose virtuosic piano style would deeply influence two generations of New Orleans piano players, including Fats Domino, Allen Toussaint, James Booker and Henry Butler. (Mac’s own early career as a guitarist would be handicapped in 1960 by a gunshot wound to his left hand, prompting a shift to piano as his primary instrument.)

Related: When Springsteen and Fogerty celebrated Dr. John

The once and future Dr. John had decamped to Los Angeles in the mid-’60s, joining other Crescent City refugees then pulling down first-call session work in the city’s studios, playing on dates with the city’s fabled Wrecking Crew. Six years later, the Gumbo sessions at Van Nuys’ Sound City Studios included many of the same hometown crew he’d drafted for the earlier albums, but instead of his own new material, he breathed authentic life into lively new versions of hometown classics. Wexler himself shared producer credit with veteran New Orleans horn player and arranger Harold Battiste, bringing added historical depth to the team.

The finished album, released on April 20, 1972, found a perfect entry point in “Iko Iko,” suggested by J. Geils Band lead singer Peter Wolf. Pop fans were already familiar with the Dixie Cups’ 1964 hit single on Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller’s Red Bird label, but Dr. John and his producers went back to its inception as “Jockamo,” a regional 1953 hit for Sugar Boy and His Cane Cutters, written by James “Sugar Boy” Crawford and featuring none other than Professor Longhair on piano.

On Gumbo’s take of the tune, Dr. John unfurls rollicking, syncopated piano arpeggios that shimmy and buck, elaborating the same Afro-Cuban clave pulse beneath Bo Diddley’s beat against Battiste’s funky, staccato horn arrangement and call-and-response backing vocals. Its lyrics wink at the rich Mardi Gras Indians tradition and the “spyboy” sentries that monitor neighborhood tribes’ strutting competition during the Fat Tuesday revels.

On “Let the Good Times Roll,” Dr. John drew from another hometown hero, Earl King, whose early ’60s hit shared its title with different songs, including another local classic co-written and recorded by Shirley Goodman, one of the backing vocalists on Gumbo, released in 1956 as half of Shirley and Lee. (Atlantic had its own hit with a third tune under that title, Ray Charles’ cover of Louis Jordan’s original composition.) Of the three songs, the King tune is the most extroverted, and in the rendition cut for Gumbo,Dr. John plays rhythm guitar and then lead on the last two choruses, modeling his solos on Guitar Slim.

Elsewhere, Dr. John pays homage to another earlyAtlantic R&B hit that would also put money into the pockets of Atlantic founder Ahmet Ertegun with a frantic take on “Mess Around,” a hit penned for Ray Charles under Ertegun’s nom du disque, A. Nugetre.

The piano’s central role in New Orleans R&B emerges as a unifying sonic thread throughout the album, underlined by its homage to Dr. John’s forbears and mentors. He salutes Huey “Piano” Smith with a concise, vivid medley of three protean rock ’n’ roll hits written by Smith and Johnny Vincent, who years earlier had tapped a 16-year-old Mac Rebennack as an A&R scout for Vincent’s Ace label.

Ultimately, however, Gumbo’s most exalted influence comes from the pianist who cast the longest shadow over the future Dr. John’s musical life, Professor Longhair, another pioneer one degree removed from the Atlantic Records saga as one of the first New Orleans artists recorded by the label.

“Big Chief” is another Earl King song written for “Fess,” who first recorded the track in the early ’60s. Its lyric boasts allude once more to the Mardi Gras tribes while doubling as a nod to a local record store and record distribution “chief” and father figure to New Orleans musicians, Joe Assunto. For the version arranged on Gumbo, Dr. John and the producers handed its twirling signature piano riff to longtime band member Ronnie Barron on organ.

Completing the album’s tribute to Longhair is “Tipitina,” a New Orleans piano classic originally recorded in 1953 for Atlantic, produced by Ahmet Ertegun, a song that Dr. John noted he could play with “dozens of different variations without getting away from Professor Longhair.” On Gumbo, Dr. John plays the song straight in what he proudly cites as a “pure, classic Longhair version.” The song’s close association not only with “Fess” but with the broader New Orleans piano tradition is reflected in its 2011 acceptance in the U.S. National RecordingRegistry. Meanwhile, it’s also the namesake for the live music venue at the corner of Tchoupitoulas and Napoleon in the city’s Uptown district, a hallowed destination for fans who make the pilgrimage to New Orleans.

Today, Dr. John is lionized as a brilliant piano player whose stylistic command of different styles spans a wide swath of music from traditional jazz to bebop, Tin Pan Alley to the Great American Songbook. His profile as a singer, songwriter and ambassador for New Orleans music kept pace. Gumbo offered the first clear testament to that depth, mapping the interconnection of styles across cultures and eras: “The origin of funk is in New Orleans, coming out of Mardi Gras music,” he told Wexler in an interview edited into the album’s annotation, going on to explain the album’s focus on “your basic 2/4 beat with compounded rhythms and syncopations added on,” an amalgam he summarizes as “good-time NewOrleans blues and stomp music with a little Dixieland jazz and some Spanish rhumba blues.”

It’s a recipe that fans of American music still savor. The good Doctor died on June 6, 2019. His recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Bonus Video: Watch the 2011 Bonnaroo Superjam performance of “Big Chief,” featuring Dr. John (whose Desitively Bonnaroo album gave the festival its name), Dan Auerbach and the Preservation Hall Jazz Band on Bonnaroo 365.

Bonus Video: Watch Professor Longhair and The Meters perform“Tipitina” on a ’70s episode of PBS Soundstage.

7 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationSaw The Doctor at a local FESTIVAL, he was the highlight on a mid-summer’s night. Enchanting.

We must never forget the musical genius known as Dr John.

Who knows when his final album is released?

Not from “Gumbo” but –

“My head is in a bad place –

But I’m having such a good time –

I been running trying to get hung up in my mind –

Really got to give myself a good talking to this time.

Just need a little brain salad surgery

Got to que my insecurity”

They just don’t to write ’em like that as anymore.

Had the chance to see the good Doctor in 2016, and passed on the tickets, thinking “Oh, I’ll see him the next time around” – Life Lesson – There was no next time around.

Do what you think you should do – gut feelings are good compasses.

Very nice to see the Night Tripper remembered –

Thank you BCB.

Excellent, excellent. Thanks for the great article. Miss him.

Of all the many Dr. John concerts I caught, he only played guitar once. He was a great lead guitar ace.

And one of my favorites is “I walk on gilded splinters” from the Gris-Gris album