On his debut solo album, Donald Fagen trades cynicism for nostalgia in a song cycle that lands midway between Proust’s madeleine and Mr. Peabody’s Wayback Machine. In tracks set in the late ’50s and early ’60s, when their author was soldiering through adolescence, he revisits the era’s aspirations and fears with the optimism and innocence of his proxy protagonists. The worldview mirrored in his sardonic tone with Steely Dan is softened, if not entirely jettisoned, in favor of songs that retain an affectionate glow.

On his debut solo album, Donald Fagen trades cynicism for nostalgia in a song cycle that lands midway between Proust’s madeleine and Mr. Peabody’s Wayback Machine. In tracks set in the late ’50s and early ’60s, when their author was soldiering through adolescence, he revisits the era’s aspirations and fears with the optimism and innocence of his proxy protagonists. The worldview mirrored in his sardonic tone with Steely Dan is softened, if not entirely jettisoned, in favor of songs that retain an affectionate glow.

Sonically, The Nightfly doesn’t sacrifice his prior band’s musical craft and technical ambition, retaining a core creative team that nets out to Steely Dan sans Walter Becker. The production credits boast a familiar battalion of first-call studio musicians and contemporary jazz and rock luminaries who had featured on the duo’s albums. Producers Gary Katz and engineer Roger Nichols, control room confederates since Becker and Fagen’s first demos for what would become that band, remained aboard after the duo quietly unplugged their partnership in the wake of the seventh Dan album, 1980’s deceptively breezy and deeply cynical Gaucho.

“I had wanted to do something by myself for a year or so,” Fagen told this writer two years later, “before we decided to ‘take a vacation’ as [New York Times journalist] Robert Palmer put it.” He agreed that the shift from a la carte songwriting to a unifying concept undergirding the set was a key departure from how he had worked with his partner and friend after 13 years. “In all the albums I did with Walter, we never said, ‘We’re going to write about as certain period or a certain motif.’”

The subjective focus on “certain fantasies that might have been entertained by a young man growing up in the remote suburbs of a northeastern city during the late ’50s and early ’60s” acknowledged in Fagen’s liner notes flipped the script from contemporary dread to period innocence, mining memories of growing up in the bridge-and-tunnel exile of New Jersey. In his 2013 memoir, Eminent Hipsters, Fagen recalls his alienation as a 10-year-old horrified at his parents’ decision to move away from his Passaic birthplace to the suburbs of Fair Lawn and later South Brunswick’s Kendall Park—cultural wastelands for a self-described “first-tier nerd” who spent much of that period “terribly lonely.”

His salvation came from what he regarded as the mythology of cultural outsiders: the hipster myth, the science fiction myth, the romantic myth and, above all, the jazz myth were escape routes from what he regarded as the “stultifying” cultural landscape of mid-century, mainstream America.

“The ‘E.T.’ in my bedroom was Thelonious Monk,” he explained. “Everything that he represented was totally unworldly in a way, although at the same time jazz, to me, seemed more real than the environment in which I was living. It was one of those developments with a thousand homes that all looked exactly the same.” His salvation came in late-night radio shows energized by hip disc jockeys spinning post-bop gospels according to Monk, Miles, Mingus, Coltrane, their elders and their acolytes.

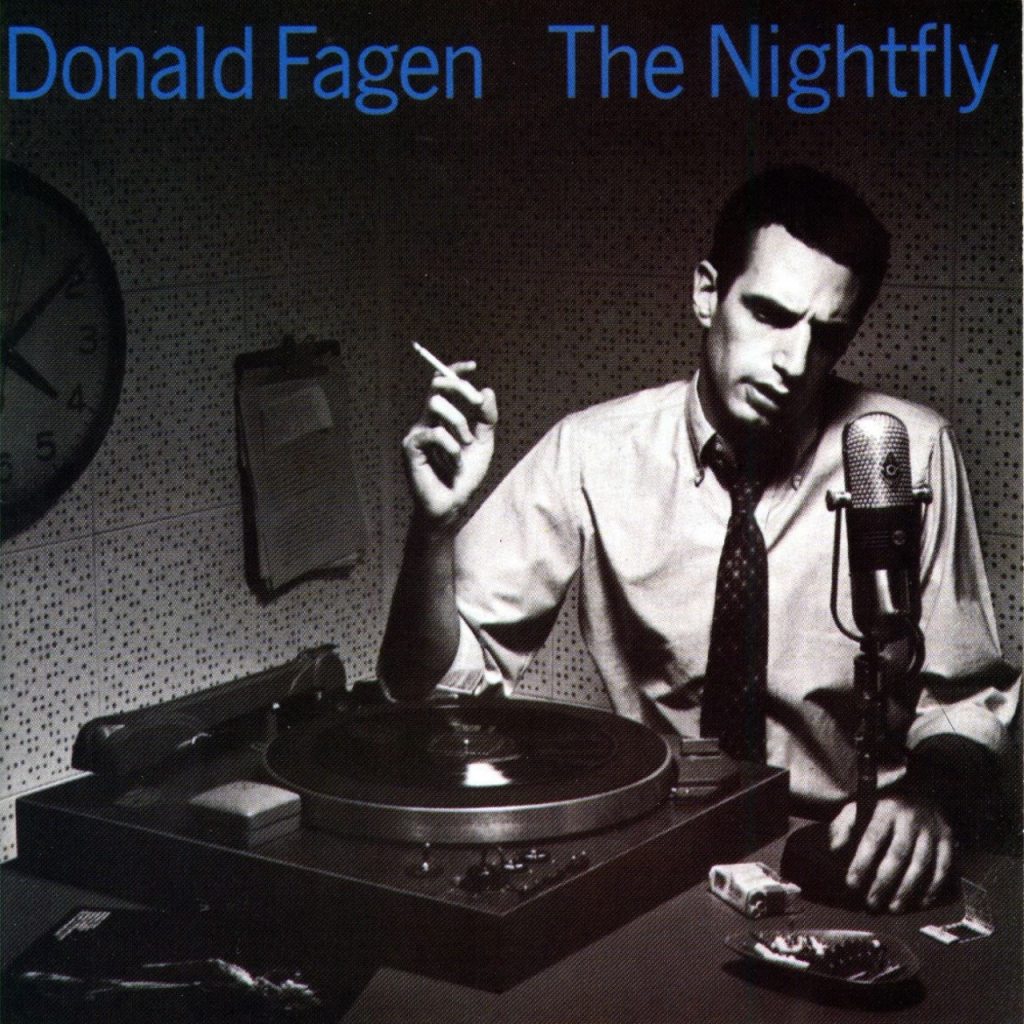

On the album’s title track, Fagen channels those radio heroes into Lester, a Baton Rouge DJ on “WJAZ’s” graveyard shift musing between calls from crackpots and spots for hair tonic namechecking Delta blues avatar Charley Patton. Powered by “plenty of java and Chesterfield Kings,” Lester’s lament for a lost love recalls the noir jazz fantasy Steely Dan projected in “Deacon Blues.” Fagen casts himself as Lester on the cover image, smoking a Chesterfield as he talks, a 1958 Sonny Rollins LP on the turntable.

The analog past celebrated on The Nightfly was significantly conjured through then-new digital technology. Steely Dan had balked on recording Gaucho digitally, but Fagen, Katz and Nichols were won over by 3M’s new 32-track and four-track digital recorders. Early session glitches prompted Nichols to head to 3M’s Minnesota HQ for digital boot camp to speed his team’s learning curve. (Fagen and Becker would eventually buy the machines themselves for their studios in Manhattan and Maui, respectively.)

At the same time they were training on 3M’s digital decks, Nichols was upgrading Wendel, the digital percussion editing system he had designed for Gaucho. Wendel II enabled even more complex composite drum tracks and could be injected directly into the 3M machines.

As one of the first all-digital studio albums, The Nightfly opens with “I.G.Y.,” a showcase for the format given added digital luster by its array of layered synthesizers and electric piano, with a silken synth arpeggio leading into the track’s gently buoyant reggae pulse, its sonic futurism balanced against a staccato horn section and Fagen’s tart “blues harp” synth filigree.

The title invokes the International Geophysical Year—a multinational collaborative science program observed from July 1957 through the end of ’58—as a wistful time stamp capturing the double vision of Cold War and space race. The lyrics offer a gee-whiz anthem laced with flag-waving optimism forecasting a world of space stations, transoceanic tunnels, solar power and “spandex jackets…for everyone.” Rising and falling incremental key changes and a languid vocal refrain (“What a beautiful world this will be, what a glorious time to be free”) hint at the broken promises in Fagen’s prophecies.

Related: Conversations with Fagen and Becker

Romantic yearning figures prominently in Fagen’s “fantasies,” another contrast to Steely Dan’s more jaundiced stance when they alluded to matters of the heart. The songs here are focused through a teenage lens. “Green Flower Street” trades in a celluloid cliché of an “exotic” forbidden love affair with “my Mandarin plum” that trades on Asian stereotypes familiar from Steve Canyon comic strips and xenophobic Hollywood pot boilers, its racism an artifact of its naïve narrator’s decidedly un-woke worldview.

The song’s title, meanwhile, offers a nod to “Green Dolphin Street,” a 1947 soundtrack theme that would take root as a jazz standard from the ’50s onward, most famously by Miles Davis’ 1959 Kind of Blue sextet.

Beyond its lyrics’ allusions to jazz, Fagen’s songwriting flexes jazz harmonies while hewing closer to classic pop forbears. His own Brill Building apprenticeship informs a ravishing cover of “Ruby Baby,” the Jerry Leiber-Mike Stoller R&B shuffle immortalized by the Drifters (1956) and Dion (1962). Fagen’s arrangement smooths tempo and expands its scale, swinging with crisp horn choruses, exuberant acoustic piano and lush, close jazz vocal harmonies that recall the Hi-Lo’s’ seminal late ’50s and ’60s vocal hits.

Romantic tropes and lush vocals carry over to “Maxine,” a Fagen ballad that complements the Leiber-Stoller valentine with its teen lovers’ familiar quandary, besotted with each other, frustrated at pushback from the grownups and juggling post-graduation dreams with sexual awakening. Vocally, Fagen is at his most persuasive here, selling post-graduation dreams of vacations and apartments in Manhattan with ardent sincerity, while his crooned delivery and choral interplay hint at his mother’s DNA as a swing vocalist who had played at Catskill clubs as a teenager.

As earthbound counterpoint to “I.G.Y.,” the album personalizes JFK’s “New Frontier” as translated by a horny teenager gearing up for a “wingding” in the family’s fallout shelter. Hormones trump nuclear anxiety on a galloping shuffle as Fagen’s party animal and would-be boyfriend flirts with a blond with “a touch of Tuesday Weld…wearing Ambush and a French twist,” a jazz fan “mad about Brubeck” who invites a salacious limbo metaphor that sounds almost courtly 40 years later.

A period-specific axis of jazz, pop and R&B is preserved on the remaining tracks. “The Goodbye Look” stays within the era if not the demographic, trading in the tropical intrigue of a lone American trying to escape from an island convulsed in a military coup, propelled by a bubbling rhythm arrangement and Fagen’s overlapping organ and synthesizer lines, conveying an ironic lightness to the lyrics’ ominous tale and the title’s finality. “Walk Between Raindrops” closes the song cycle with an upbeat reverie for a distant lover, enshrined in a rain-soaked Miami memory that again toys with cliché to end The Nightfly on a winking romantic note.

Commercially, The Nightfly, released on Oct. 1, 1982, was a disappointment for Fagen, falling short of Steely Dan’s final triumph with Gaucho, but critically the set fared better, and its technical execution signaled a best-case audiophile capability for digital recording. (It also served as a cautionary test of CD mastering when initial copies were mastered from an analog sub-master rather than the digital master tape, a blunder caught by Roger Nichols.)

Donald Fagen would keep a low profile for the rest of that decade before reuniting with Walter Becker in the early ’90s to resurrect Steely Dan for a triumphant tour, with Becker producing Fagen’s sophomore solo album, Kamakiriad, and Fagen returning to favor to co-produce Becker’s own solo debut, 11 Tracks of Whack.

Listen to Fagen perform “Ruby Baby” live from the Orpheum Theatre

The album is available here. Steely Dan’s catalog is being reissued on vinyl. The recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNice article, but…

1. You’re mixing Fagen with Sam Cooke. The chorus to I.G.Y. is “what a BEAUTIFUL world.”

2. The last song is “Walk Between Raindrops.” No “the” in the title.

“mackdaddyg”… Thanks for catching those.

Thanks for your perceptive summary. It’s interesting that at least one of the tunes, “The Goodbye Look”, has become mainstream enough in sound (if not in lyrics) to have been covered by Mel Tormé!