‘Young Americans’ at 50: Behind the Scenes, Studio and Stage

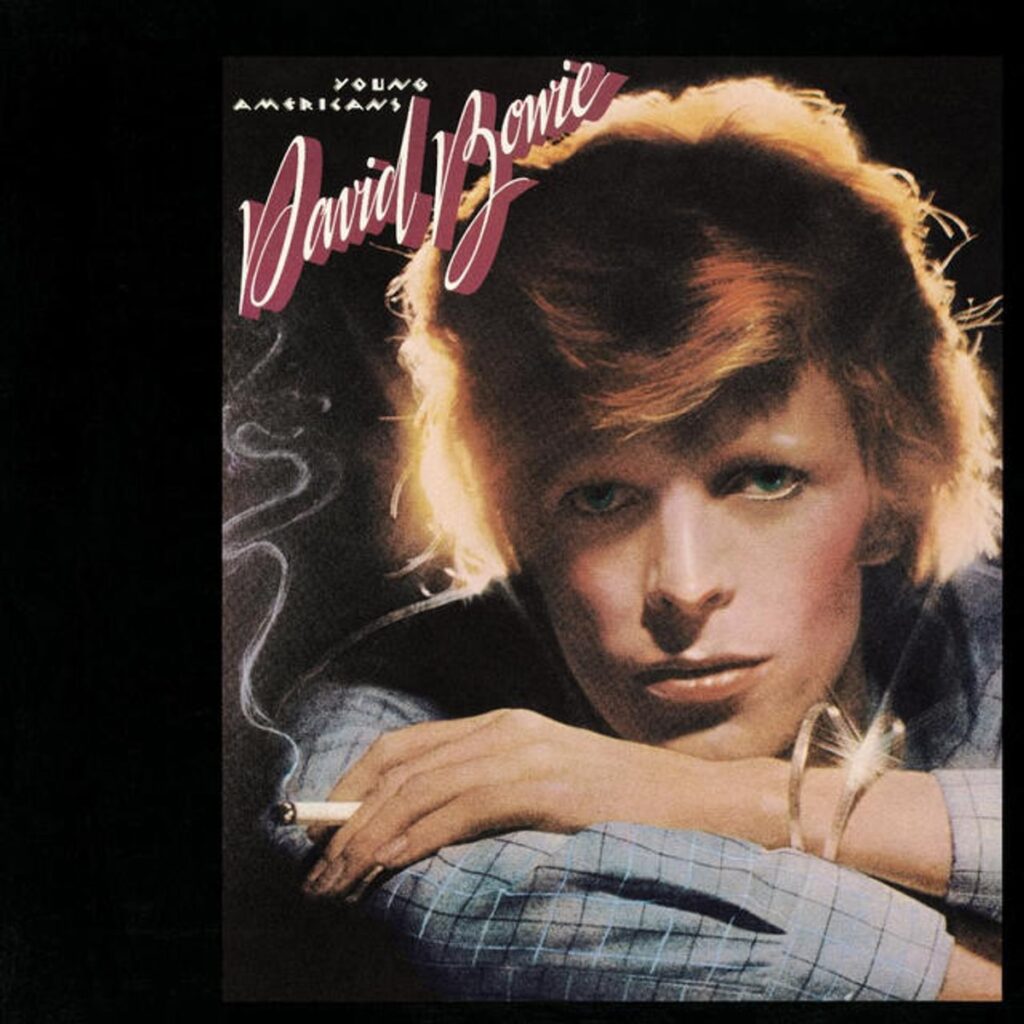

by Harvey Kubernik March 7, 2025, marked the 50th anniversary of the release of David Bowie’s ninth studio album, Young Americans. On the exact day of its Golden Jubilee, Young Americans was reissued by Rhino as a limited-edition half-speed-mastered LP and as a picture disc pressed from the same master, the latter with a poster. [Both are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

March 7, 2025, marked the 50th anniversary of the release of David Bowie’s ninth studio album, Young Americans. On the exact day of its Golden Jubilee, Young Americans was reissued by Rhino as a limited-edition half-speed-mastered LP and as a picture disc pressed from the same master, the latter with a poster. [Both are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

This new pressing of Young Americans was cut on a customized late Neumann VMS80 lathe from the original Record Plant master tapes, with no additional processing on transfer. The half-speed was cut by John Webber at AIR Studios.

The album saw Bowie broaden his musical horizons once more, and would give Bowie his first #1 single in the U.S., “Fame,” co-written with John Lennon and Bowie’s then-guitarist, Carlos Alomar.

The LP was partly influenced by the “Philly Sound”—the R&B hits spearheaded by Gamble and Huff—and recorded in Philadelphia at Sigma Sound Studios during a break in the Diamond Dogs tour with a band that included, among others, Bowie stalwart Mike Garson on keys, Luther Vandross on vocals and David Sanborn on saxophone. Tony Visconti produced the sessions at Sigma.

Many other musicians also informed this dazzling endeavor: guitarists Earl Slick and Larry Washington, Robin Clark, Ava Cherry; Diane Sumler, Anthony Hinton, Jean Millington and Jean Fineberg on backing vocals; Pablo Rosario, percussion; drummers Dennis Davis and Ralph MacDonald; and bassists Willie Weeks and Emir Ksasan.

When the Diamond Dogs tour recommenced, Bowie radically reworked the setlist to incorporate the new material and stripped the elaborate production of the tour back to reflect a new musical direction.

At the end of the tour in December 1974, sessions continued at the Record Plant and, while recording in New York, Bowie connected with John Lennon, and they recorded a cover of the Beatles’ “Across the Universe” and a new collaborative composition, “Fame,” at Electric Lady Studios. The New York sessions were co-produced by Bowie and Record Plant engineer Harry Maslin.

Bowie opted not to tour following Young Americans’ release, and within nine months, he had moved on again, releasing his next album, Station to Station, reinventing himself once again in the persona of the Thin White Duke.

Listen to the title track from Young Americans

This writer spoke with Mike Garson in 2002. Bowie’s longtime pianist discussed the Young Americans album.

‘“Fascination,’ is a great song,” he said. “[It featured] David Sanborn on sax. ‘Somebody Up There Likes Me.’…I love that song [and the] prodding, slow beat on the studio recording. Luther Vandross was a background vocal genius. He would bang out every note to make those background vocals sound amazing. David was the best at finding the right people: Mick Ronson, Luther Vandross, Carlos Alomar, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and let them do their thing. Whatever I had practiced I could do.”

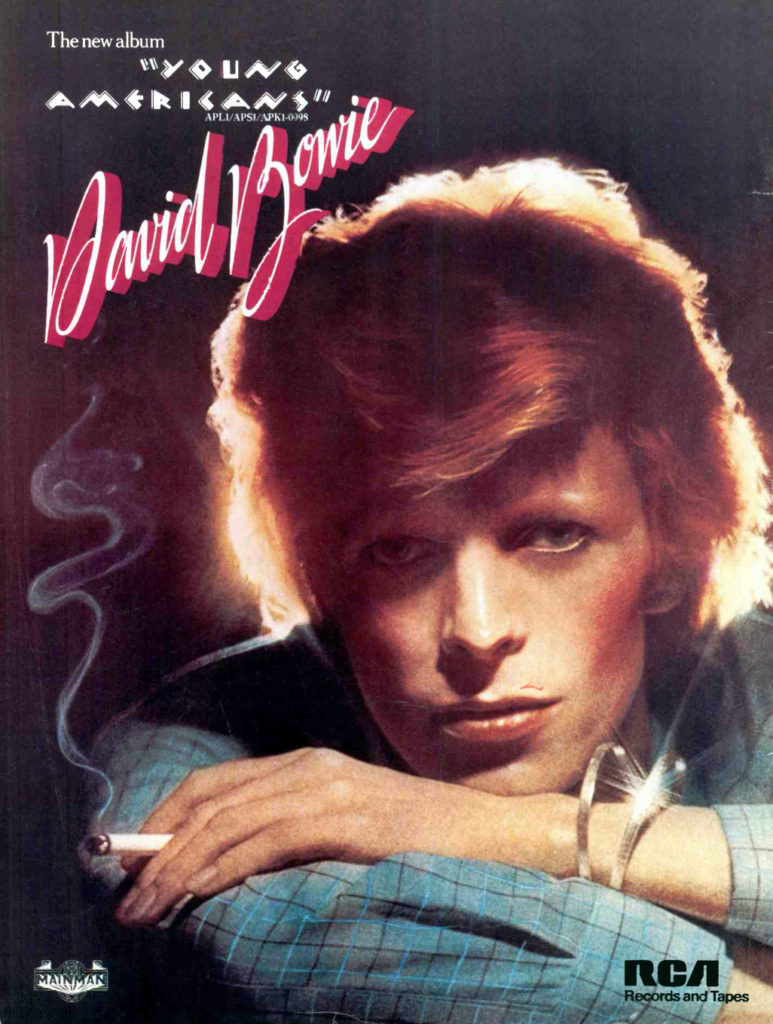

This ad for the Young Americans album appeared on the back cover of the March 15, 1975 issue of Record World

“Young Americans is just a masterpiece LP on every level—soulful, serious, a meditation on all his big themes of alienation, loneliness and the 20th century hall of mirrors,” said writer and novelist Daniel Weizmann.

“Forget the costumes, that was just decoy. Bowie—like Steely Dan, Love and the Doors—was a dark explorer of reality. With this one he took [John] Rechy’s City of Night (referenced by the song “Fascination”) and spun the disco ball for a hypnotic disco dystopia.

“You see, here in nostalgia-land, it’s easy to forget how scarily, almost willfully superficial, the ’70s often were. Despite Altamont and Manson—or maybe because of them—much of the younger generation was hellbent on clinging to cosmic lift-off, white-knuckled. Here in Hollyweird, everywhere you looked it was astrology, crystals, ‘new age’ cultiness, and escapism. Even rock music, which had prided itself on shrewd rebel spirit, was starting to cave to gnomes, elves, and all manner of fairytale b.s.

“Not Mr. Bowie—for all his powers of enchantment, he never let go of the hard truths. Take the title track, this poignant kitchen sink drama about two young people in the throes of losing their innocence, yearning for a perfection they will never have. The epic bridge breaks into a kind of judgment rap as Bowie excoriates them with a blast of hard facts—they aren’t glamorous, these two, and never will be. They’re utterly defeated, and fate is going to make quick work of them. But Bowie is pained by his own judgment, and finally he cops to it: he too yearns for the ‘young American,’ the impossible dream.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars

“My favorite is the second track, though—it might be his ultimate masterpiece, ‘Win,’ a Nietzschean critique of modernity disguised as crooner soul! Why, he seems to be challenging the listener, do you think you can hide behind the superficial and live a life without fighting, without caring, without honor and dignity and defeat and rebirth? Bowie has been called a lot of things…except the thing he was most, a humanist,” Weizzmann summarized.

“I agree that Young Americans is a masterpiece on every level, but I hear things in it that Daniel Weizmann leaves unmentioned,” added writer, poet and DJ Dr. James Cushing.

“I agree that Young Americans is a masterpiece on every level, but I hear things in it that Daniel Weizmann leaves unmentioned,” added writer, poet and DJ Dr. James Cushing.

“Bowie’s move in a soul-jazz-dance direction (goodbye Mick Ronson, hello Luther Vandross and David Sanborn) was impossible to predict from Aladdin Sane and Pin Ups, but in retrospect, it shows how he was never to be pinned down to one style or one mode or one ‘character.’ The album is a declaration of freedom, specifically the freedom of reinvention. He sings in a different register than he does on the Ziggy albums and the tunes have a more open structure.

“The tenderness he shows on ‘Sweet Thing/Candidate’ comes to the forefront on ‘Win,’ ‘Right,’ ‘Can You Hear Me’ and even on the uptempo numbers like ‘Fascination’ or ‘Fame.’ Only ‘Across the Universe’ seems out of place.”

In 1974, during Bowie’s Diamond Dogs tour, this author spent half an hour with him at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel. We talked about Beat generation literature and R&B music while glimpsing an episode of Soul Train on television. There was a commercial for a hair product, Afro Sheen. In Bowie’s “Young Americans” he sings, “Blushing at all the Afro-Sheeners.” We both attended the local Al Green concert at the Universal Amphitheater.

I gave Bowie a paperback copy of Ann Charters’ Jack Kerouac: A Biography, knowing his Spiders from Mars band name was an homage to Kerouac’s On the Road: “exploding like spiders across the stars.” Charters’ book is seen by his hotel bedside in the Omnibus Cracked Actor 1975 U.K. documentary, which aired on the BBC 1 channel.

In Bowie’s hotel suite, his record player was stacked with albums of Stax, Motown and LP jackets that read “Produced by Gamble and Huff.” Even after a walk to his car there was an Isley Brothers’ tape on his front seat. When I met with Rod Stewart for an interview at the Beverly Wilshire, he remarked, after listening to the opening guitar riff on Young Americans, “Sounds like David has been listening to Isaac Hayes’ theme from Shaft.”

On September 18, 1975, I interviewed Bowie himself in Los Angeles at Television City, inside the CBS studios on the corner of Fairfax Ave. and Beverly Blvd. Bowie was taping the Cher TV show for a November 9 broadcast. (Afterwards, I was introduced to Cher. “I adored working with him and was delighted to have him on the show,” she said, beaming.)

Watch Bowie and Cher duet on “Young Americans”

In my brief 1975 dialogue with Bowie for England’s now-defunct Melody Maker, he commented on his just completed feature-length movie, The Man Who Fell to Earth. Some of the soundtrack was done at Cherokee Studios, up the street from the CBS TV studio. It was obvious that Bowie had already departed visually, musically and emotionally from the self-imposed world of his Ziggy Stardust character into his current cinematic journey.

“The difference between film acting and stage acting is enormous,” he said during our interview. “On stage you are in total control, whereas in a film the actors are instruments of the director. I think a stage performance is more of a ceremony and one plays the high priest. But in a film, you are evoking a spirit within yourself. You feel a tremendous responsibility of having the power to bring something to life. For example, Major Tom in ‘Space Oddity.’”

At the Cher taping, I wrote at the time, “Bowie wore high-cuffed yellow pants with sport shirt and blue jacket; he seemed perfectly dressed for a Miami vacation. However, he still takes his work seriously and his face was rigid and working with nervous energy. No bodyguards, or hangers-on this time around.”

Between takes, Bowie and Cher engaged in some nifty bump and grind moves while the band tuned up. They were two of the slimmest bodies in show business. Bowie and also I talked about “Fame,” and the song’s then-current breakout on soul stations, also owing a bit to the fact that John Lennon was involved with the recording. Having watched Soul Train with him, I asked if Bowie entertained any thoughts of a Soul Train spot promoting “Fame.”

“Don’t you think that would be pushing it a bit?” he readily replied. He was happy at his current single success, but added, “I had a lot of other singles here that didn’t do anything.”

(Bowie subsequently did appear on Soul Train series, miming to “Golden Years” and “Fame.” He also appeared as an interview subject in the Don Cornelius-hosted Soul Train documentary that was released on DVD in 2010).

The night before the Cher taping I witnessed, Bowie was laying down some demos at Cherokee Studios on Fairfax, where we listened to a playback of “John, I’m Only Dancing.” It would go on to become another of his classic tunes.

“I’m convinced we’ll never see another like him, not in pop music anyway,” offered Daniel Weizmann.

“He embodied so many radical contradictions in one artist that he forced you to reconsider pop itself. He was literature but he was street jabber. He did narrative rock opera but he did it fragmented, so that any slice of the story could be a credible Top 40 single. Strip away all of it, the costumes, the larger-than-life shtick, and at his core he was just so damn good.

“Most of all, he always vibed two intense contradictions in everything he did. On the one hand, he was the ultimate masked performer, the Faker. But on the other hand, while ‘being the Faker,’ he was singing about being a lonely cosmopolitan, Wasteland, the alienated 20th century man lost in a nightmare dreamscape called reality.

“How lucky were we that David Bowie happened?!”

Watch Bowie’s complete 1975 appearance on Soul Train

[Author and music journalist Harvey Kubernik’s books are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationGreat nuggets on the one-and-only who left us too soon! Really enjoyed reading this!