Rock ’n’ roll was still in its first decade of pop disruption when, in 1956, Chuck Berry taunted opera and classical music, telling Beethoven to “roll over… and tell Tchaikovsky the news.” But over the next few decades, as the ranks of rock fans swelled with the post-war baby boom, artists, producers and songwriters remained more than willing to mine those older musical seams in pursuit of new hits.

Rock ’n’ roll was still in its first decade of pop disruption when, in 1956, Chuck Berry taunted opera and classical music, telling Beethoven to “roll over… and tell Tchaikovsky the news.” But over the next few decades, as the ranks of rock fans swelled with the post-war baby boom, artists, producers and songwriters remained more than willing to mine those older musical seams in pursuit of new hits.

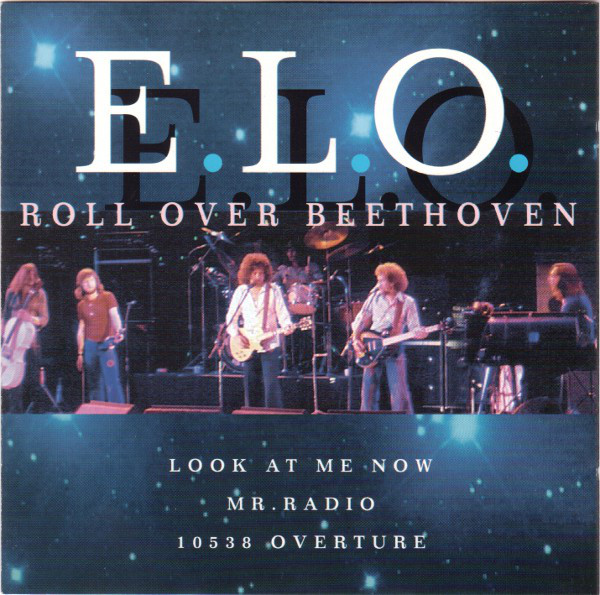

By the time England’s Electric Light Orchestra recorded their cover of Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven” in 1973, it wasn’t considered strange at all that they incorporated actual Beethoven music into their version. (Scroll down for the full story of the ELO cover.)

The meshing of rock and the classics goes back at least to the early ’60s. Ever ready to cash in on a new novelty, producer, songwriter, scene-maker and future Runaways Svengali Kim Fowley exploited Tchaikovsky to score a hit with “Nut Rocker,” the 1962 instrumental cribbed from the Russian composer’s beloved ballet score for The Nutcracker and credited to B. Bumble and the Stingers, which hit #23 on the U.S. singles chart and topped the singles chart in the U.K.

Three years later, songwriters Sandy Linzer and Denny Randell scored gold when they transformed J.S. Bach’s “Minuet in G major” into “A Lover’s Concerto,” a major girl-group hit that exploited its sophisticated melodic structure to blur the line between verse and chorus. As recorded by the Toys, the song swapped the original composition’s waltz time for a brisk 4/4 meter, going on to peak at #2 on Billboard’s U.S. singles chart, blocked by the one-two punch of the Beatles’ “Yesterday” and the Rolling Stones’ “Get Off My Cloud,” and reaching #5 on the U.K. singles chart

That same year saw another familiar Bach melody grafted onto a newer kind of “longhair” music, the folk-rock of the Byrds. Released on Oct. 29, 1965, as the B-side of their hit “Turn! Turn! Turn!,” Gene Clark’s “She Don’t Care About Time” was a graceful, uptempo love song that took flight with a classic Roger McGuinn Rickenbacker 12-string solo that quotes Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring,” a chorale from a 1723 cantata that could, in hindsight, rightly be called one of Johann Sebastian’s major hits.

(That same melodic theme would shape a lesser late-’70s Beach Boys track, co-written by original member Al Jardine, “Lovely Lynda.”)

Over the years since, Bach’s towering influence beyond the baroque epoch he defined would extend repeatedly to pop, rock and jazz. Beyond direct citations of his vast catalog, Bach’s stylistic inventions and mathematical precision in devising intricate fugues would surface in the keyboard stylings of rock’s most proficient keyboard players.

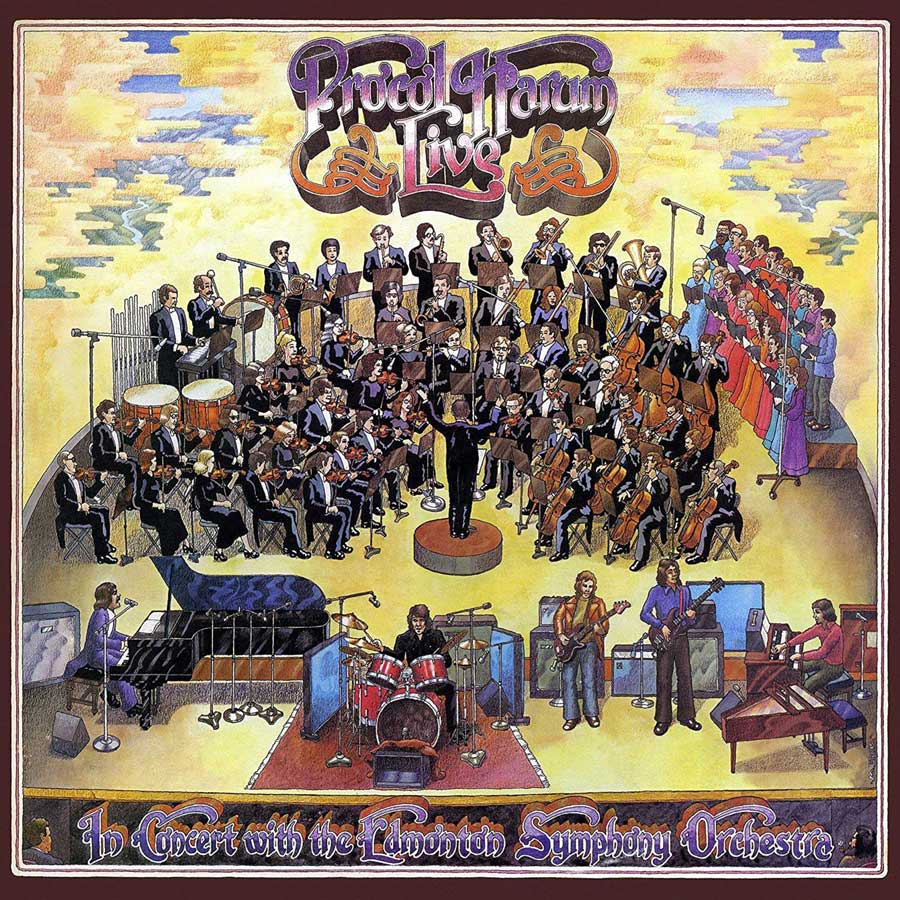

Few musicians derived greater impact from the Leipzig composer’s melodic gifts than Procol Harum organist Matthew Fisher, who adapted Bach’s “Air on a G String” for the evocative organ theme that haunts the British band’s massive 1967 hit, “A Whiter Shade of Pale.” Throughout the Summer of Love, the song’s hypnotic juxtaposition of a stately chamber sound and surreal lyrics that obliquely referenced Geoffrey Chaucer’s “The Miller’s Tale” established the song’s unique impact.

Few musicians derived greater impact from the Leipzig composer’s melodic gifts than Procol Harum organist Matthew Fisher, who adapted Bach’s “Air on a G String” for the evocative organ theme that haunts the British band’s massive 1967 hit, “A Whiter Shade of Pale.” Throughout the Summer of Love, the song’s hypnotic juxtaposition of a stately chamber sound and surreal lyrics that obliquely referenced Geoffrey Chaucer’s “The Miller’s Tale” established the song’s unique impact.

Related: The story of “A Whiter Shade of Pale”

While lead singer and pianist Gary Brooker and lyricist Keith Reid were credited as the song’s creators, Fisher would later contest that authorship in a 2005 suit, asserting that Fisher’s instrumental framework was integral to the song, ultimately gaining credit and royalties in a subsequent House of Lords ruling modifying an earlier partial award. Regardless of who split the financial pie, the Procol Harum track had already entered the rock canon: In 1977, “A Whiter Shade of Pale” split honors with Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” as Best British Pop Single, 1952-1977 at the Brit Awards, and in 1998, the song entered the Grammy Hall of Fame.

(That same summer’s global swoon over the impact of Sgt. Pepper likewise factors into a heightened readiness to adopt classical elements, epitomized by the Moody Blues’ plunge into symphonic arrangements on Days of Future Passed, released in November 1967.)

Related: Our Album Rewind of Days of Future Passed

Procol Harum’s earlier incarnation as the Paramounts, an earthier R&B-flavored rock outfit, offers a parallel to another quintet that would memorably nod to Bach, The Band.

As Ronnie Hawkins’ backup band, the Hawks, the Canadian-American group included multi-instrumentalist Garth Hudson, a musical polymath who excelled at free-range keyboard stylings; the group’s graduation to its own style after its fertile collaboration with Bob Dylan unleashed Hudson’s more eclectic influences and technical ambition. In “Chest Fever,” the hardest-rocking song on Music From Big Pink, their 1968 debut full-length, he forges an extended organ intro that riffs on the musical thunderbolts in Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor,” then shifts gears as the song careens into a truly feverish groove. Onstage, “Chest Fever” would become a reliable high point in their live shows as Hudson improvised and elaborated on his original baroque organ inspiration to establish that introduction as its own delirious piece, “The Genetic Method.”

Another Bach warhorse, the Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G major, surfaced that year via Keith Emerson and the Nice, downsized from its chamber ensemble setting to Emerson’s surging Hammond organ and released as the British band’s third single. That turbo-charged adaptation wasn’t their first foray into classical repertoire, however: Earlier in ’68, they released “America,” a self-described “protest instrumental” that fused the Leonard Bernstein-Stephen Sondheim song from West Side Story with one of the main themes in Antonin Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 in E Minor (better known as his New World symphony) that serves as its introduction.

The Nice and Procol Harum weren’t the only British groups dipping into the classics and setting the stage for the explosion of prog-rock at the turn of the decade. In his first album helming his own band, Jeff Beck turned in a typically searing guitar showcase on “Beck’s Bolero,” taking the familiar theme of Maurice Ravel’s single-movement symphonic Bolero. (In the current millennium, Beck would tackle “Nessun Dorma,” the show-stopping tenor aria from Puccini’s Turandot.)

Like the Jeff Beck Group, Jethro Tull had been hatched as a blues-rock band fronted by multi-instrumentalist Ian Anderson and guitarist Mick Abrahams, but Anderson’s determination to broaden its scope led to a split with Abrahams, replaced by guitarist Martin Barre. Tull leaned into jazz and, yes, classical sources on their second album, 1969’s Stand Up, with Anderson performing a swinging update of Bach’s “Bourée in E minor” on flute.

The Move, the flamboyant Birmingham band led by Roy Wood, stretched beyond psychedelia with 1970’s Shazam, their third album, which boasted a classical triple play on the delirious “Cherry Blossom Clinic Revisited,” which offered another spin through Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring,” a Rick Price bass solo that quoted Paul Dukas’ symphonic poem, “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” and the “Tea” dance from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker.

That same period saw Love Sculpture, the Welsh band fronted by Dave Edmunds (with fellow future Rockpile drummer Terry Williams), notching a commercial career best with their fiery guitar-driven take on Aram Khachaturian’s “Sabre Dance,” a move regarded as a mere novelty ploy for a group that had otherwise steered close to the blues. By the end of that year, the band dispersed.

Progressive rock’s early ’70s emergence saw classical influences continue both explicitly and obliquely. Emerson, Lake & Palmer found ex-Nice organist Keith Emerson continuing to dip into classical sources, most broadly on the trio’s third album, 1971’s Pictures at an Exhibition, which adapted Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky’s familiar suite, originally composed for piano but later expanded into numerous orchestral arrangements, for a live concert by the trio. EL&P would also salute American composer Aaron Copland on subsequent albums with their versions of his “Hoedown” from Copland’s Rodeo ballet and his anthemic “Fanfare for the Common Man.”

Inevitably, rockers turning to the classics gravitated to many of the same crowd-pleasers that mainstream classical orchestras and performers relied upon in their programming. Consider the broad reach for “In the Hall of the Mountain King,” the minor-keyed earworm from Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt suite, which spawned jazz, pop and then rock covers from 1941 onward. Earlier covers by Big Brother and the Holding Company (a 1966 live performance from a TV taping) and the Who (both live and studio performances from 1967, unheard until the ’90s) made the piece low-hanging fruit for Electric Light Orchestra.

ELO’s own genesis was inspired by the neoclassicism inherent in the Beatles’ expanded palette from Sgt. Pepper on. The Move’s Roy Wood and his newest recruit, Jeff Lynne, disbanded the group to launch a new lineup that would prominently feature strings. Wood left the partnership after its debut album, leaving Lynne to lead the new group (which also included former Move drummer Bev Bevan), which recorded their own version of the Grieg piece on the band’s third album.

ELO’s own genesis was inspired by the neoclassicism inherent in the Beatles’ expanded palette from Sgt. Pepper on. The Move’s Roy Wood and his newest recruit, Jeff Lynne, disbanded the group to launch a new lineup that would prominently feature strings. Wood left the partnership after its debut album, leaving Lynne to lead the new group (which also included former Move drummer Bev Bevan), which recorded their own version of the Grieg piece on the band’s third album.

Related: The inside history of ELO

As sweeping as that nearly seven-minute mash-up was, however, Lynne and his bandmates had already scored with a classical warhorse on the previous album by connecting two very prominent dots: “Roll Over, Beethoven,” introduced by Beethoven’s most recognizable symphonic theme, the first movement of his Fifth Symphony, which was woven throughout their rave-up on the Chuck Berry standard.

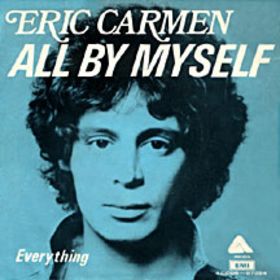

The ’70s witnessed other classical adaptations that borrowed from the canon to power pop, disco and even a rare hit jazz track. Eric Carmen left behind the power pop glories of the Raspberries to achieve his biggest solo hit with 1976’s “All By Myself,” a sweeping orchestral pop ballad that drew its melody from Sergei Rachmaninoff’s romantic Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor (also the source for “Full Moon and Empty Arms,” a 1945 hit for Frank Sinatra that Bob Dylan would include on the first of his three recent albums of pre-rock pop covers; Carmen would also lift a melody from the same composer’s Second Symphony for his other big hit of that year, “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again”).

The ’70s witnessed other classical adaptations that borrowed from the canon to power pop, disco and even a rare hit jazz track. Eric Carmen left behind the power pop glories of the Raspberries to achieve his biggest solo hit with 1976’s “All By Myself,” a sweeping orchestral pop ballad that drew its melody from Sergei Rachmaninoff’s romantic Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor (also the source for “Full Moon and Empty Arms,” a 1945 hit for Frank Sinatra that Bob Dylan would include on the first of his three recent albums of pre-rock pop covers; Carmen would also lift a melody from the same composer’s Second Symphony for his other big hit of that year, “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again”).

Related: Our feature on Carmen, who died in 2024

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony reappeared as a disco workout for Walter Murphy and the Big Apple Band, which topped the U.S. singles chart the same year that Carmen scored with Rachmaninoff.

Meanwhile, Brazilian composer, arranger and keyboard player Eumir Deodato two years earlier snagged the Grammy for Best Pop Instrumental performance with “2001,” his simmering fusion setting for Richard Strauss’ anthemic tone poem “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” which had emerged as the theme song for Stanley Kubrick’s visionary 1968 sci-fi epic, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

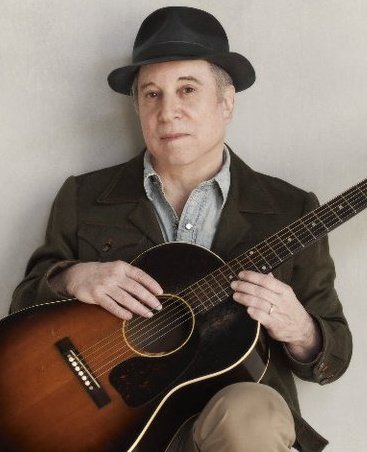

If high drama remains the most frequent draw for pop and rock artists tapping into the classics, one of the most elegant derivations remains Paul Simon’s “American Tune,” recorded for his second solo album, There Goes Rhymin’ Simon. Among Simon’s most beautiful songs, it draws its melody, harmonic progression and much of its counterpoint directly from “Mein G’müt ist mir verwirret,” a chorale in J.S. Bach’s majestic St. Matthew Passion.

Composed during the final year of the Nixon presidency, the song serves as a wistful meditation on the American dream in peril. Surveying the battered souls and shattered dreams of his countrymen, Simon gazes across two centuries of the country’s history as he tries to reconcile hope with disappointment:

“We come on the ship they call the Mayflower

We come on the ship that sailed the moon

We come in the age’s most uncertain hour

And sing an American tune…”

Simon has noted his general avoidance of explicitly political songs, preferring to touch upon those themes obliquely, yet as first heard in 1973, “American Tune” served as a eulogy for a generation whose activism and optimism seemed eclipsed by the moral failures of Vietnam and Watergate. If anything, the song has only gained power in the years since. Covered by a diverse array of artists, it has become an unofficial national hymn, more relevant than ever.

- ‘Running on Empty’: Jackson Browne’s Romance of the Road - 12/06/2025

- ‘Slowhand’: Eric Clapton’s 1977 Platinum Balancing Act - 11/25/2025

- Stephen Stills’ A-List Solo Debut Revisited - 11/16/2025

12 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationBilly Joel certainly borrowed from the classical palette quite liberally, but one direct lift of note was the song “This Time” on the Innocent Man album which credits “L.v.Beethoven” as a writer. The tune was from Beethoven’s “Pathetique” sonata.

You should also list ‘Daydream’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_wFMY0r7X-w the world-wide hit of the Belgian band ‘Wallace Collection’ which borrows a theme from Tchaikovsky’s ‘Swan Lake’

Barry Manilow famously borrowed from Chopin’s Prelude in C-minor (Prelude 20 from Opus 28) for his 1973 hit, “Could It Be Magic”.

And then there’s this one: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ekQ1RTmzBc

Amazingly, this otherwise thorough piece missed RENAISSANCE (1970-2020+) which quoted classical pieces fused into rock in many of their songs i.e., At The Harbour, Prologue, using classic opera trained lead singer Annie Haslam.

ELPs live version of Nut Rocker on Pictures at an Exhibition is something else. As is the whole album.

A couple of videos from the same content creator that goes into more songs withe the ‘classical’ treatment:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yknBXOSlFQs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qA-tkCRwNVM

In another interesting tidbit, Eric Carmen borrowed from “Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor” by Rachmaninoff for his 1975 hit song “All by Myself”.

It’s a long article, Teddy, but that nugget about Carmen is already in the story.

Love Sculpture dipped into classic a second time. The flip side of “in the land of the few” single was a rock version of Bizet’s Farandole

What about Dan Fogelberg’s “Another Old Lang Syne” borrowing from Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture?

One you missed, though you do mention the group…the intro and bass line on The Move’s debut single Night Of Fear was from Pyotor Ilyich in the 1812 Overture. Great track.