By 1979, the juice had been wrung out of punk. The raw energy and exhilaration—and low barrier of entry—that made punk so exciting also made it easy pickings for the kind of martinet who sees any tug against orthodoxy as a capital crime. “Loud Fast Rules” quickly changed from a rallying cry to a straitjacket, “rules” sliding from a verb to a noun.

By 1979, the juice had been wrung out of punk. The raw energy and exhilaration—and low barrier of entry—that made punk so exciting also made it easy pickings for the kind of martinet who sees any tug against orthodoxy as a capital crime. “Loud Fast Rules” quickly changed from a rallying cry to a straitjacket, “rules” sliding from a verb to a noun.

The Clash was none too fond of rules, in any form, even self-applied, an attitude that was probably both their strongest and weakest attribute. Though their 1977 British debut is one of punk’s founding documents (their “1977” single—with the refrain “No Beatles, Elvis or the Rolling Stones”—was as much a manifesto as the Sex Pistols “Anarchy in the UK”), it eschewed the scorched earth policies of the Sex Pistols, reaching outside the bounds of doctrinaire punk, touching on reggae and pre-Beatles rock. They were properly truculent about the music business, but for all their complaints about their record label (even recording “Complete Control” to protest the label’s choice of a single), they wanted to sell records, and agreed to have Sandy Pearlman produce Give ’Em Enough Rope, their second album (but first released in the States), in the hope of attracting an American audience.

It didn’t, in part because it was a mismatch from the start. While his work for Blue Öyster Cult and the Dictators might have led the label to believe he was the man who could make the Clash palatable to American ears, the result was a shiny botch of an album, one that sanded all the personality off of the band. Pearlman reportedly despised Joe Strummer’s voice, and his vocals are buried deep in the mix, under an avalanche of compressed, EQ’d and echoed guitars. For all the punch Pearlman gave their sound, the band seemed to be pulling theirs.

It also emptied out the Strummer/Jones songbook, so after their second tour of the States, the Clash was at a crossroads. They had to figure out what kind of band they wanted to be, and in typical Clash manner, went for a complete teardown: they fired their manager, Bernard Rhodes, moved into a new rehearsal studio and set about writing and demoing new songs. But when it came time to hire a producer, they threw a curve: Guy Stevens, best known for helming Mott the Hoople’s pre-Bowie albums, and for an anarchic style of producing.

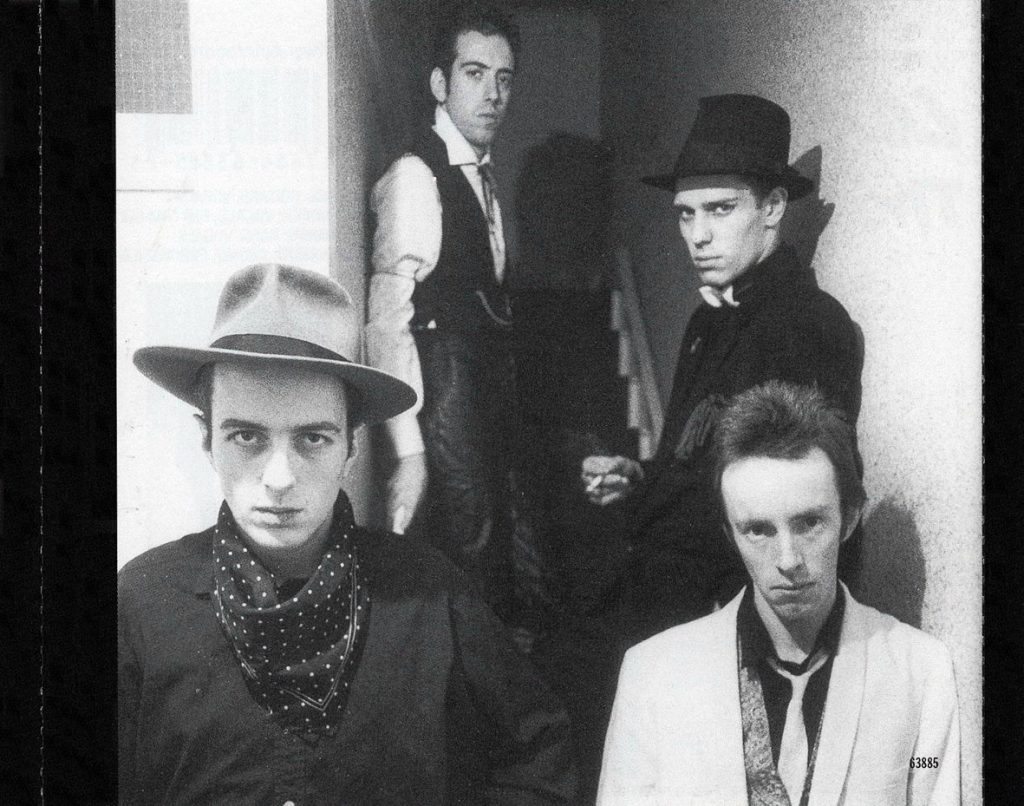

Classic Clash in a London Calling publicity photo (clockwise from left): Joe Strummer, Mick Jones, Paul Simonon, Topper Headon.

The stories of Stevens’ manner of creating an atmosphere of creativity and freedom are legendary. Alcoholic and on his last legs (he would die 18 months after London Calling’s release), he would smash furniture, swing a ladder, throw bottles across the room—at one point, pouring a bottle of wine into the body of a grand piano—anything to goad the band into the performance he was looking for.

The Clash, who were never that organized an outfit to begin with—even when they were firing on all cylinders, they were just as likely to shoot themselves in the foot as hit the target—responded in their usual contrarian fashion by getting down to business and producing arguably their best album.

It was released on December 14, 1979, in the U.K. (and Jan. 14, 1980 in the U.S.) and is a sprawling collection. The songs wandered over a dizzying range of styles, but felt very much of a piece. London Calling, as much as any album of the period, holds up a mirror to England as Thatcherism takes hold. Following the title track, a martial beat calls to action, the harsh Tory policies conflated with the Three Mile Island nuclear meltdown, the album is a tour of the Clash’s London. It was a city where people turned to drugs, booze, empty consumerism and easy fascism for relief. Jimmy Jazz, Ivan and Rudie were based on real people, and Strummer really did live by the River Thames, taking the number 19 bus (named-checked in “Hateful”) to get to the rehearsals.

Interspersed among the character studies were songs that took a broader view, whether of war—“Spanish Bombs” connects the anti-Franco fighters in World War II with separatist terrorist bombings that took place during a trip Strummer took to Spain—or pop culture—“The Right Profile,” inspired by Strummer’s reading of Patricia Bosworth’s biography of Montgomery Clift—or the good life promised by advertising in “Koka Kola” and the working class dead end promised by the Tories in “Death or Glory.” The latter includes one of Strummer’s most trenchant lyrics: “He who f**ks nuns/will later join the church.” And it wouldn’t be the Clash without at least some self-mythologizing, taken care of quite well with “Four Horsemen” and “I’m Not Down.”

The sounds heard on the album also reflected what you would hear on London’s streets. The reggae of Paul Simonon’s “Guns of Brixton” and a cover of the Revolutionaries’ “Revolution Rock”; ska—mixed with New Orleans—a cover of Clive Alphonso and the Rulers “Wrong ’Em Boyo,” with elements of “Stagger Lee” and the horn part from Frankie Ford’s “Sea Cruise.”

The album’s other cover, Vince Taylor’s “Brand New Cadillac,” started out life as a song the band played while warming up in the studio. Stevens insisted they play it again. But mostly, London Calling sounded like the Clash, a great, if flawed rock band ready to see the new decade and expand the vocabulary of British rock. They had so many great songs, they nearly gave away “Train in Vain” as a promotion for the New Musical Express; it fell through at the last minute, so it was added to London Calling, but not listed on the cover or label. The song that broke the band in the U.S. was a hidden track—it reached #23 in Billboard, and helped the album itself vault to #27, a far higher placement than its two predecessors.

Watch the Clash perform “Train in Vain” live

Related: What are some of the other great 2-LP studio sets?

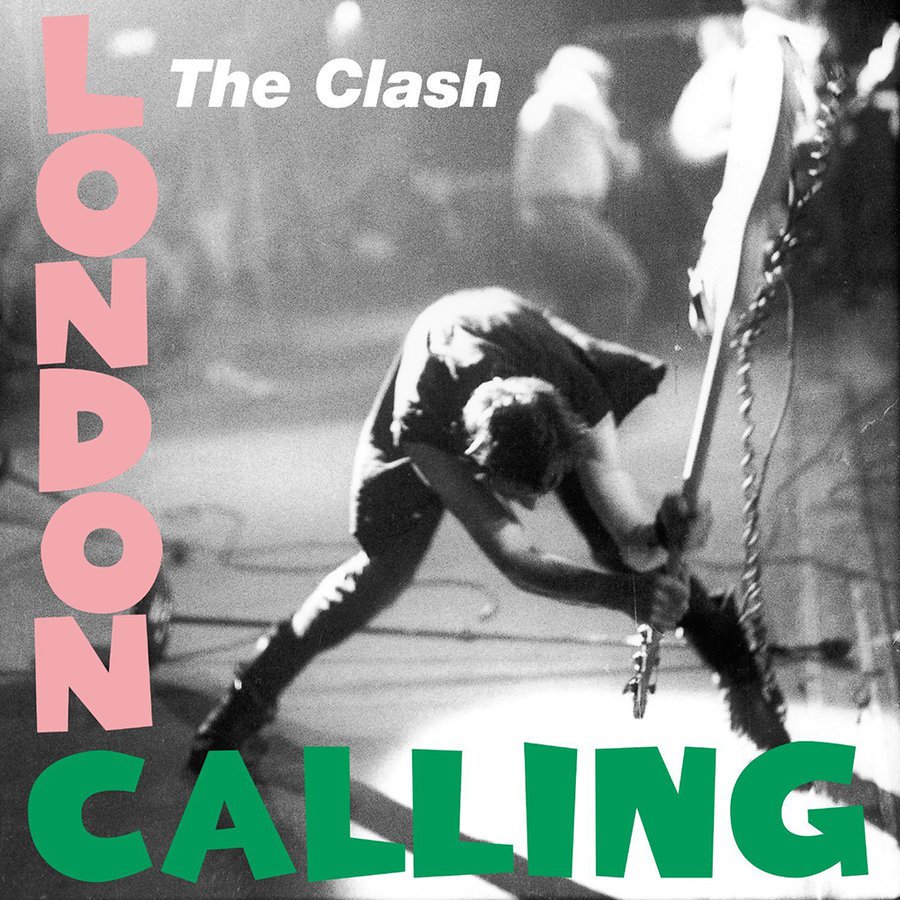

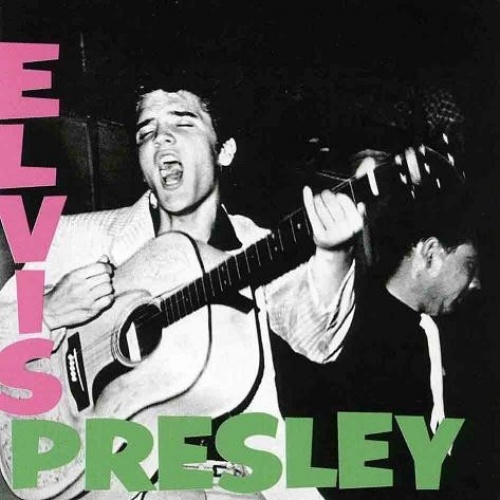

Of course, you can’t talk about London Calling without mentioning its album cover. A shot of Simonon smashing his bass in frustration during a show at New York’s Palladium, with lettering that echoed the color and design of Elvis’ debut album, it perfectly represented the music inside—cathartic and exciting, ready to both push past and nod to rock ’n’ roll’s past.

Of course, you can’t talk about London Calling without mentioning its album cover. A shot of Simonon smashing his bass in frustration during a show at New York’s Palladium, with lettering that echoed the color and design of Elvis’ debut album, it perfectly represented the music inside—cathartic and exciting, ready to both push past and nod to rock ’n’ roll’s past.

It couldn’t last. The Clash was simply too unstable a band to keep the momentum going. What initially seemed like a step up ended up being a high water mark. But what a high water mark! [The album is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Watch the official video for the title track from London Calling

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationWhat a great band. They ruled the early 80s.I still get chills when I play “London Calling”