With their seventh studio album, Mardi Gras, released in the spring of 1972, Creedence Clearwater Revival sputtered out with what is generally regarded as their worst album. Their leader, songwriter, lead guitarist/vocalist and primary sound designer John Fogerty had just seen his older brother Tom quit the band after years of conflict. For the first time John yielded considerable room to bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug Clifford, who co-produced and contributed their own compositions, lead vocals, and arrangements. Clifford and Cook later suggested that it was all a ruse to break up the group, as John Fogerty refused to work in good faith with them on their songs. The only hits on the album were “Sweet Hitch-Hiker” and “Someday Never Comes,” both written and sung by John.

With their seventh studio album, Mardi Gras, released in the spring of 1972, Creedence Clearwater Revival sputtered out with what is generally regarded as their worst album. Their leader, songwriter, lead guitarist/vocalist and primary sound designer John Fogerty had just seen his older brother Tom quit the band after years of conflict. For the first time John yielded considerable room to bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug Clifford, who co-produced and contributed their own compositions, lead vocals, and arrangements. Clifford and Cook later suggested that it was all a ruse to break up the group, as John Fogerty refused to work in good faith with them on their songs. The only hits on the album were “Sweet Hitch-Hiker” and “Someday Never Comes,” both written and sung by John.

On October 16, 1972, Fantasy Records announced the band’s dissolution, but John Fogerty was still bound to the label as a solo artist, under economic conditions he found increasingly intolerable. CCR had been generating most of Fantasy’s revenue for some time, and Fogerty felt he should have been rewarded with part ownership of the label, a demand owner Saul Zaentz rejected. “I felt like I was their little prisoner in their dungeon,” he told journalist Adam Sweeting in 2000, “their little mouse in a cage that they played with. To take somebody that was at their height, like Elvis or the Beatles, and then treat them so badly is really a horrible thing.”

In April 1973 Fantasy released a new album from Fogerty, but there was a catch. He had prepared a solo album of a dozen country, bluegrass and gospel tunes, none written by him. Fogerty had been thinking about such an album at least since CCR’s tour of Japan in February 1972, when he jammed on some songs with Clifford and Cook in their hotel rooms. He was also influenced by informal song-swaps with CCR’s longtime opening act Tony Joe White.

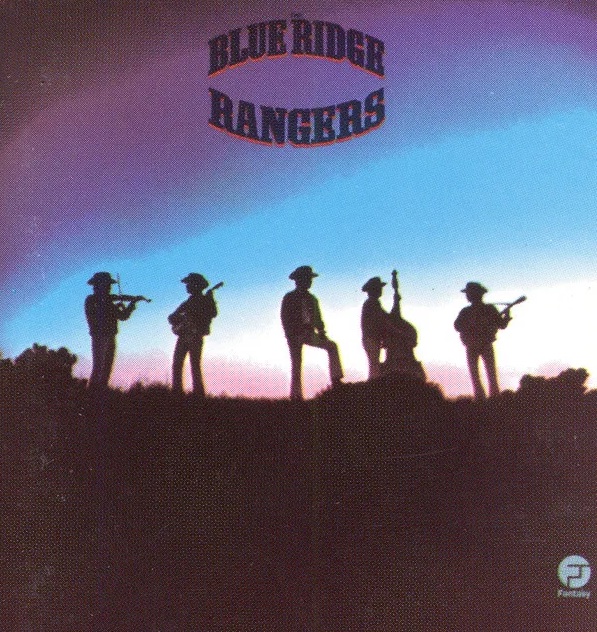

For the new sessions at Fantasy Studios, Fogerty produced, arranged and played all the instruments, but insisted it be credited to a fake band, the Blue Ridge Rangers, riffing on the pre-CCR band name Blue Velvets. For the cover of the self-titled album, John’s brother Bob Fogerty took some purposely generic photos of silhouetted musicians in Stetsons. Skip Shimmin and Russ Gary are listed as engineers on the back liner, along with a modest “arranged and produced by John Fogerty” designation. The battle between Fantasy and Fogerty had entered its Cold War phase.

Related: John Fogerty talks about writing “Proud Mary”

The track list mixes tunes by well-known songwriters (Hank Williams, “The Singing Brakeman” Jimmie Rodgers, Merle Haggard, Mel Tillis) and more obscure material (“Have Thine Own Way, Lord,” the 1907 Christian hymn by Adelaide Pollard, recorded by Jim Reeves, among others). Fogerty had shown his affection for folk, gospel and R&B during the CCR days, recording Lead Belly’s “Midnight Special” and “Cottonfields,” Arthur Crudup’s “My Baby Left Me,” Jay Hawkins’ “I Put a Spell on You,” etc., so it was no surprise he could dig deep into what later became known as Americana for his debut solo LP.

The banjo-driven opener is “Blue Ridge Mountain Blues,” a traditional folk song that had been recorded as early as 1924, and which Fogerty discovered, according to a promotional interview he did for Fantasy in 1973, on a J.E. Mainer LP, “buried right in the middle…it stood out like a great big concrete building in a desert. The song really grabbed me right away.” Fogerty says it “became kind of my own personal little national anthem or something; it’s one of my favorite songs of all kinds of music—it’s one that I rate in my own top 10.” He plays creditable fiddle and dobro for this fast Texas two-step, and multi-tracks his vocal in well-chosen spots.

“Somewhere Listening (For My Name)” was first recorded by the Original Five Blind Boys in 1953, and was written by group leader Archie Brownlee. Fogerty picked it up from an LP on the French Vogue label called Negro Spirituals, which he bought in 1971 while on tour with CCR in Europe. Here the multi-tracked vocals provide the crucial call-and-response, and Fogerty roughens up his lead vocal, as he often did with Creedence, managing to invoke a whole history of black gospel from Claude Jeter to Little Richard. Two songs in, and Fogerty has already managed to nail very different, distinct styles, and a third is around the corner.

As recorded on the tiny Crest label by Bobby Edwards, “You’re the Reason” did well on both country and pop charts in 1961. Fogerty responded to the pleading in Edwards’ voice when he heard it on the radio, probably on the venerated Oakland AM station KWBR. According to his 1973 interview, Fogerty leaned his vocal toward Hank Williams instead of merely imitating Edwards. And his steel guitar work is great.

The Hank Williams classic “Jambalaya (On the Bayou)” is next, with Fogerty arranging proceedings more like Bob Wills’ Texas Playboys than Williams himself (including a quick falsetto in the concluding moments). The twin-guitar solo in the middle is a delight, and Fogerty’s sincerely-fake Louisiana accent, familiar from any number of Creedence records, makes an appearance. The legitimately Louisiana-born Tony Joe White suggested Fogerty record it after they played around with it on tour: good choice. Released as a single, it got to #16 in Billboard. Listen to it below.

“She Thinks I Still Care” was best known from the killer version recorded in 1962 by George Jones, but it was Merle Haggard’s later approach to the tune that affected Fogerty the most. The arrangement came alive in the studio as Fogerty tried out different combinations of instruments: “I was knocked out when I found that little twinkling piano thing in the background. It was just enough. I didn’t have to come in with 29 violins or something, just to let you know there’s music behind it. It’s one of those classic songs where the vocal and the content are more important than the music,” he asserted in that 1973 promotional interview for Fantasy’s publicity department.

“California Blues (Blue Yodel #4)” was also inspired by Haggard, one of the tracks on his tribute to Jimmie Rodgers, Same Train, Different Time. Acoustic guitar and dobro, stand-up bass and lightly brushed drums start things off, in one of the album’s best arrangements. There’s a clarinet/sax section which Fogerty handles too— he’d played saxophone on CCR’s “Travelin’ Band”—and the keening steel guitar makes another appearance. It’s a laid-back performance, an obvious illusion when you concentrate on how much planning and discipline it must have taken to have at least 12 Fogerty parts woven together.

The original LP’s second side begins with the traditional gospel tune “Workin’ on a Building,” which came from African-American churches but was quickly adopted by white congregations. Fogerty no doubt knew recorded versions by the Carter Family and Bill Monroe, but it was the Stanley Brothers’ version that burrowed into his musician’s brain. On compilation tapes he would make for friends, he put the Stanley Brothers’ take right after Ray Charles’ “Drown In My Own Tears,” connecting different styles.

“Workin’ on a Building” is The Blue Ridge Rangers’ longest track, and fulfills Fogerty’s desire to “put in all the fire he wanted it to have,” in the words of a Fantasy press release. He varies the rhythm approach (including a section of foot-stomping and hand-clapping), plays some cutting lead electric guitar, and creates a blues-gospel chorus from umpteen overdubs. It’s one of the few songs from the album that show up later in live performances during Fogerty’s long solo career, as he continues to find new power to mine in it.

“Please Help Me, I’m Falling,” written by Don Robertson and Hal Blair, was first recorded by Hank Locklin in 1960, reaching #1 on the U.S. country charts and nearly that high on the pop charts. Fogerty explained that the song always reminded him of truck-stop cafes, where he and his brother Tom would pump their nickels into the jukebox, playing the Locklin 45, Elvis’ “My Baby Left Me” and other country-pop hybrids. Fogerty puts on his best “countrified” voice, for once sounding a bit artificial, but listen to his steel guitar work if you get tired of his voice.

Fogerty grabbed “Have Thine Own Way, Lord” from the Country Gentlemen’s 1950 version. Heart on his sleeve, Fogerty handles the stacked harmonies perfectly, focusing the arrangement on the voices with only a few touches of steel and acoustic guitar in support.

Fogerty’s peppy version of “I Ain’t Never” is based on the crossover hit version Webb Pierce released in 1959. Fogerty rocks it up, and takes a couple of stabs at his own Pierce-style Fender guitar solos. (When Dave Edmunds records “I Ain’t Never” a year or so later, it sounds like he’s aware of Fogerty’s version and consciously makes decisions that will set his take in neither Pierce nor Fogerty camps.)

“Hearts of Stone” is an R&B tune released originally done by the San Bernardino group the Jewels in 1954. Cincinnati doo-wop crew Otis Williams and the Charms covered it the same year and had the nationwide hit. Fogerty was reportedly trying to write an original song something like “Hearts of Stone” when he finally gave up and recorded the original, but messed with it until it sounds like an outtake from Elvis Presley’s Sun sessions. The rhythm’s pretty much rockabilly, but the guitar solos vary in approach as Fogerty absolutely wails out the lyrics in his characteristic rasp. “Hearts of Stone” was the second single Fantasy released from the LP, but it barely scraped into the Billboard Top 40.

The Merle Haggard/Bonnie Owens classic “Today I Started Loving You Again” concludes the album with some hardcore country. Fogerty shows restraint in tackling the melancholy lyrics: “I got over you just long enough to let my heartache mend/And then today I started loving you again.” He doesn’t have Haggard’s baritone, but he acquits himself well.

The Blue Ridge Rangers, released in late April 1973, peaked at #47 on the Billboard LP chart, but Fogerty wasn’t through with the concept, going so far as to plan a second volume. Two new tracks, “You Don’t Owe Me” and “Back in the Hills,” were issued as a single in September 1973 but didn’t chart at all. No doubt Zaentz was getting fed up with indulging Fogerty’s non-commercial, non-rock enthusiasms, but Fantasy president Ralph Kaffel later insisted, “We had a good relationship during the Blue Ridge Rangers album. He called all the shots and basically wrote his own ticket for everything. When he finally put out a record under his own name—‘Comin’ Down the Road’—it bombed. Even though we did not drop the ball, I think he held us responsible.”

For his part, Fogerty basically went on strike and refused to record for Fantasy, and the stand-off lasted until he was released from his obligations and signed with David Geffen’s Asylum Records, releasing his second solo LP, John Fogerty, in autumn 1975. Two tracks, “Almost Saturday Night” and “Rockin’ All Over the World,” became minor radio hits, but failed to establish Fogerty any further. Asylum declined to release the follow-up Hoodoo, and Fogerty went back into seclusion. It would take a switch to Warner Bros. Records and the comeback of “The Old Man Down the Road” and the Centerfield album in 1985 to make him a star again on a permanent basis.

In 2009, Fogerty released The Blue Ridge Rangers Rides Again, picking more of his (and his wife Julie’s) favorite songs, the Everly Brothers’ “When Will I Be Loved” and Ray Price’s “I’ll Be There” among them. But he didn’t play all the instruments or sing every line, calling in friends like Don Henley, Kenny Aronoff, Buddy Miller and Bruce Springsteen, and was using the old band title to indicate the “feel” of the sessions and his sense of nostalgia about the original LP, conceived during a time in which he was, to say the least, ambivalent about being part of the star-making machinery.

Listen to Hank Williams’ “Jambalaya (On the Bayou)” from the album

Fogerty’s solo albums are available here.

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationLOVE this album!

Especially “Workin On the Buildin.”

Unbelievable thoroughness of the information contained in this article – one of the reasons BCB is such a treasure.

The Blue Ridge Rangers is a brilliantly performed LP of covers of country/traditional songs (Merle Haggard, Hank Williams, Mel Tillis, Jimmy Rodgers, etc.

John Fogerty was also essentially a one-man band on the “John Fogerty” album of 1975, as well as well as on “Centerfield”.

This reinforces that John Fogerty was, and always will be, CCR embodied in one extremely talented musician, vocalist, and songwriter – who also happened to work with a tight knit band of a talented drummer, bassist, and rhythm guitarist during CCR’s run.

I need to dig deeper on this album, which I bought on CD around 10 years ago. Played his take on “I Ain’t Never” (a Mel Tillis song!) on my oldies show back a few months ago.

Ik vind ook dat John Fogerty de grootste input had bij CCR. Hij schreef bijna al de liedjes.

En zijn krachtige stem is heerlijk.

Ook solo heeft hij goede albums gemaakt waaronder the Blue Ridge Rangers.

Ik vind het jammer dat HOODOO nooit is uitgebracht, want ik heb er nummers van gehoord en vind ze verrassend goed. John schrijft hele mooie teksten.

Hij hoort bij de beste songwriters thuis.

Hij wordt 28 mei 80 jaar, en treedt nog steeds op.

Ik hou van John’s muziek. En dat doe ik al 45 jaar. Elke dag luister ik wel naar een van zijn albums.