‘John Barleycorn’: From Winwood Solo Project to Traffic Reunion

by Sam Sutherland When Steve Winwood entered the studio in February 1970, time and technology were poised for his graduation from front man in a rock band to full-fledged solo artist. At 21, the Birmingham native was already a seasoned veteran who had played pub gigs at 8, taken center stage with the Spencer Davis Group at 15 and helped pioneer rock’s progressive wing with Traffic before joining Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker in Blind Faith. His soul-drenched vocals had reaped hits for all three groups, while his frontline prowess on organ and piano were matched by solid chops as a guitarist, bassist and percussionist. The evolution of multi-track studio recording would enable him to roll his own songs by layering instrumental performances as a one-man band.

When Steve Winwood entered the studio in February 1970, time and technology were poised for his graduation from front man in a rock band to full-fledged solo artist. At 21, the Birmingham native was already a seasoned veteran who had played pub gigs at 8, taken center stage with the Spencer Davis Group at 15 and helped pioneer rock’s progressive wing with Traffic before joining Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker in Blind Faith. His soul-drenched vocals had reaped hits for all three groups, while his frontline prowess on organ and piano were matched by solid chops as a guitarist, bassist and percussionist. The evolution of multi-track studio recording would enable him to roll his own songs by layering instrumental performances as a one-man band.

Accompanying him to his first sessions was producer and Island Records A&R director Guy Stevens, whose confidence in Winwood was assured by the artist’s role in establishing Island as a preeminent British independent label. Founded in 1958 by Chris Blackwell, Island’s growth relied upon Blackwell’s embrace of Jamaican music, nurtured from his childhood on the island. While promoting his first major hit act, ska pioneer Millie Small, Blackwell witnessed the Spencer Davis Group at a Birmingham television taping and saw a fresh direction in its teenage lead singer and organist.

“He was really the cornerstone of Island Records,” Blackwell would later assert. “He’s a musical genius and because he was with Island all the other talent really wanted to be with Island.” Island’s founder would bankroll Winwood’s departure to form Traffic and would prove an ardent supporter for decades to come.

Blackwell and Stevens were confident that Winwood was ready to stand alone and suggested an album title, Mad Shadows. Initial studio sessions followed the original one-man band premise for the first completed song, “Stranger to Himself.” Written by Winwood with lyrics from Traffic’s Jim Capaldi, the track featured Winwood on piano, acoustic and electric guitars, bass, drums and percussion. His instincts as an arranger had already been honed extensively with Traffic, enabling him to craft a satisfying dialogue between guitars and keyboards, anchored by in-the-pocket bass and drums.

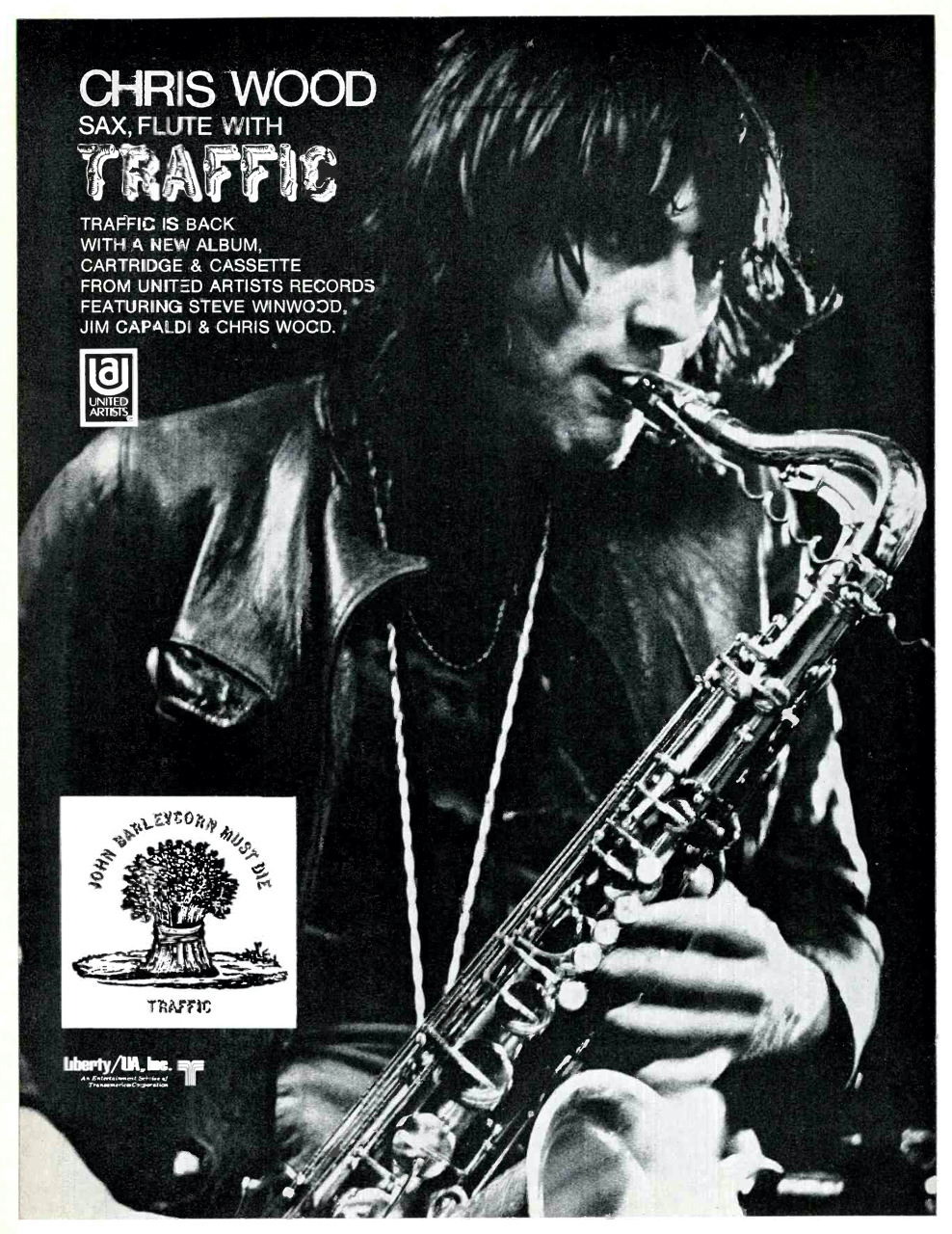

Next up was “Every Mother’s Son,” with Winwood again covering keyboards, guitars and bass, and Capaldi sitting in on drums and percussion. If producer Stevens was happy with the results, however, Steve Winwood chafed at the isolation of self-contained performances. With Capaldi onboard as drummer and vocal partner, Winwood invited fellow Traffic alumnus Chris Wood to join in on reeds, percussion and organ, effectively reuniting the core trio that had been Traffic’s more durable configuration during an initial two-year run in which guitarist, vocalist and songwriter Dave Mason had proven a fickle partner in his on-again, off-again ties to the band.

At this juncture, Stevens departed the project, presumably on good terms, while taking the tentative album title with him, which he would recycle for Mott the Hoople’s second album, produced and released that same year. Blackwell, meanwhile, stepped in as nominal co-producer while clearly allowing Winwood to retain a dominant role in shaping the material, which still showcased his versatility while reveling in the trio’s interplay. That focus was punctuated by “Glad,” a Winwood instrumental that would open the album with a full-throttle keyboard romp reflecting his enduring affection for jazz and R&B in a hard-driving, uptempo workout with echoes of ’60s soul jazz classics from Jimmy Smith, Jack McDuff and Les McCann as Winwood traded rippling piano flourishes against textured Hammond B-3 organ. Wood’s tenor sax deepens the groove and adds a prescient funk element by using a wah-wah pedal to electronically mute his horn lines.

Apart from the saxophone and flute parts that signified Traffic’s jazz elements, Wood also brought the band vital exposure to material it might otherwise have missed. Winwood would credit the reed player with turning them on to jazz, world music and classical pieces that opened their ears to new directions, but for this album, Wood’s gift would come from deep British roots—the renascent interest in British folk music that emerged during the ’60s. Wood’s interest in the movement had led him to the Watersons’ a cappella recording of “John Barleycorn,” a ballad that can be traced to its earliest Scottish incarnations in the 16th century, its title character linked both to pagan Anglo-Saxon myths and a personification of the hardy grain used in producing whiskey.

Traffic’s arrangement of the song jettisons keyboards, electric guitars and bass in favor of a haunting lattice work of acoustic guitar, flute and spare hand percussion. Winwood’s vocal is by turns hushed and mournful as he presents the allegorical fate of its title protagonist “ploughed,” “sown” and “harrowed in” by efforts to kill him. As men continue to harvest, dry, mill and process their victim, they carry him toward reincarnation and revenge—by the song’s end, “little sir John with his nut-brown bowl proved the strongest man at last,” mortal men now dependent on its distilled essence.

Chris Wood was the focus of this ad for the album in the July 18, 1970 issue of Record World.

Winwood’s delicate performance was both dark and sardonic, ancient in its source yet timely in its allusion to addiction—an inevitable nod to a countercultural subculture which Traffic had once romanticized with a psychedelic palette.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Traffic’s Mr. Fantasy album

With its timeless minor-keyed melody, spare setting and Winwood’s pure English vocal intonation, the track is the album’s most distinctive, yet Traffic would otherwise revert to its prior jazz, blues and rock influences, leaving a deeper excavation of British folk rock for Pentangle, Fairport Convention, Steeleye Span, the Incredible String Band and other homeland folk-rock pioneers to explore. It’s fascinating to contemplate how Traffic’s stature as a major rock act might have elevated and influenced Britain’s spin on fusing folk tradition with rock innovation had Winwood and his partners committed more fully to the style.

As Traffic’s lyricist, Capaldi alternates between emotional impressionism and oblique romantic salutes, the latter yielding the album’s lone single, “Empty Pages,” released only in the U.S. By the time of the album’s early July 1970 release, the rise of FM radio and rock’s evolving focus on albums over singles vindicated the trio’s disinterest in mainstream single hits, eventually carrying John Barleycorn Must Die to #5 on Billboard’s album chart, the highest position in the band’s career.

Critics were more divided over the album’s emphasis on loose-limbed jamming, with Robert Christgau complaining that Mason’s exit had weakened their songcraft, leaving them to depend on Winwood’s “feckless improvised rock.” Fans, however, were kinder: Beyond its album chart ranking, John Barleycorn Must Die would earn gold record status, teeing up the band for even greater success with The Low Spark of High-Heeled Boys the following year.

[The album is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

BONUS VIDEO: Watch Steve Winwood’s live performance of “John Barleycorn (Must Die),” captured at his home in England’s Cotswold district in 2012.

BONUS AUDIO: Hear The Watersons’ 1965 a cappella version of “John Barleycorn (Must Die),” the inspiration for Traffic’s ethereal 1970 studio recording. From the album Frost and Fire.

6 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationSteeleye Span also did a version of “John Barleycorn Must Die” on their “Below the Salt” album, but they used a very different tune (and interpretation) from Watersons/Traffic.

Great album…there is also a nice cover of John Barleycorn…. on the Jethro Tull “A Little Light Music’ album.

One cannot say enough good things about Steve Winwood. I fell in love with the voice the first time that I heard ‘Gimme Some Loving’

While it’s a terrific landmark record, it does still come across as a Winwood Solo effort despite the inclusion of two of his Traffic bandmates. Also, in terms of Traffic records, it’s a transitional record in terms of the way Traffic albums would sound going forward. For starters, JBMD eschewed the more “village” type sound (for lack of a better descriptor) of their previous records, eliminating the use of multiple voices, and of many background vocals in general, elevating Winwood’s to pretty much the only voice you hear, a practice he continued on most Traffic and Winwood solo records and live performances going forward to this day. And while Barleycorn doesn’t feature any of the much-used percussive sounds, that create the many musical feels and stylings that Traffic had previously featured as a big part of their sound on their previous records, Barleycorn is like a demarcation point where forever after this surprisingly un-percussive straight ahead record congas will be forever employed as a part of Traffic’s sound as a constant, for better or for worse. The fact that this is the first “Traffic” album which is completely devoid of any Dave Mason involvement is also a significant factor, as without Mason, Traffic, and their subsequent Winwood-centric recordings would always have a different sound and feel which is less band-like. All in all, a truly great record, but at the same time, kind of the death knell of what was formally an incredibly original and entertaining band.

This album ranks as one of the top in my collection in the last 50 years. It’s just truly a Seminal release start to finish. There’s not a bad song on the record. Stranger to himself is fantastic and empty pages is always fun to listen to loud.

I got to see the reunion tour in summer 1970 (?). At the end of the show they lined the band up at the exit and everyone shook their hands upon leaving. Pretty weird but cool nonetheless.