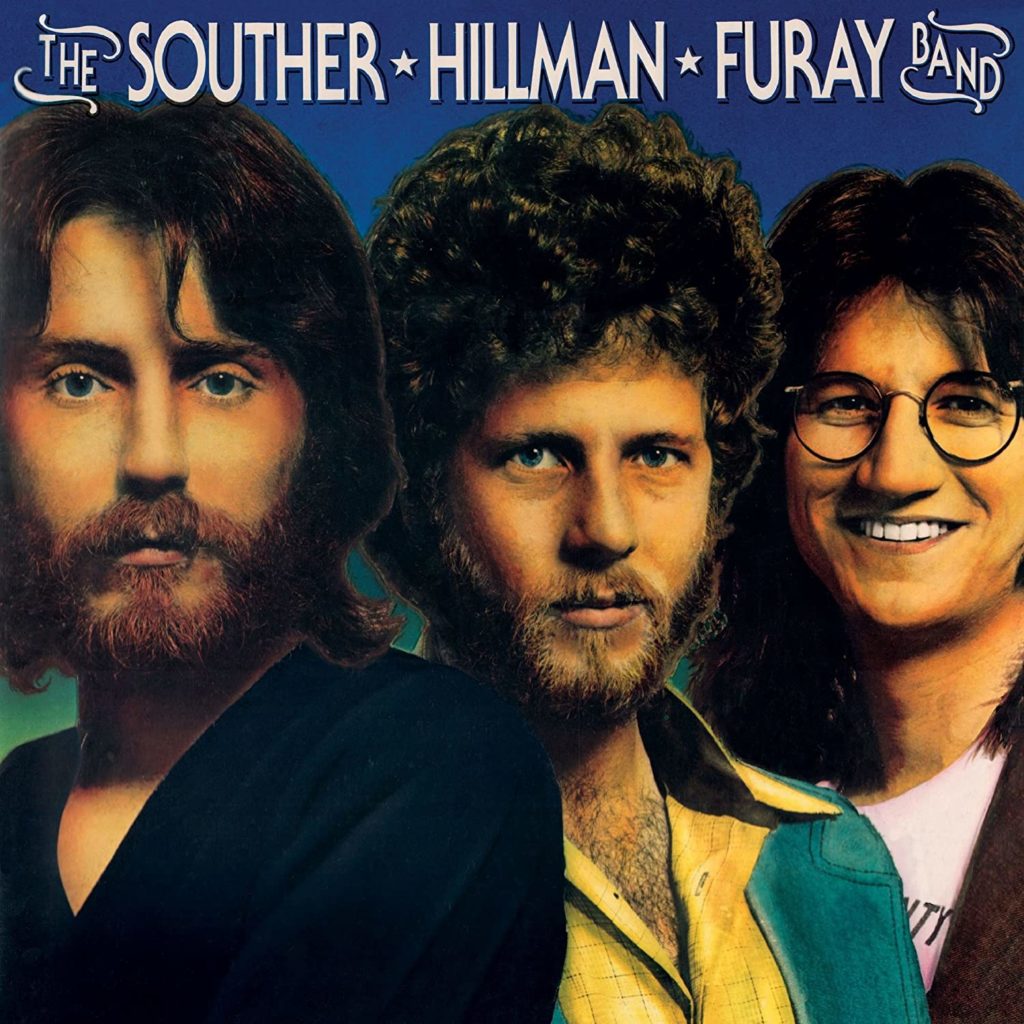

The Souther Hillman Furay Band’s Debut LP: Less Than the Sum of its Parts

by Sam Sutherland In 1973, artist manager David Geffen was basking in the success of Asylum Records, his boutique label launched two years earlier with the backing of Atlantic Records. Emboldened by the commercial success of the Eagles, Asylum’s first band, and his earlier triumph managing Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, Geffen proposed another would-be supergroup by lobbying John David Souther, Chris Hillman and Richie Furay to join forces. With prior band bona fides, songwriting experience and their own shared affinity for country-rock, the trio seemed poised to cash in on California’s ’70s rock gold rush.

In 1973, artist manager David Geffen was basking in the success of Asylum Records, his boutique label launched two years earlier with the backing of Atlantic Records. Emboldened by the commercial success of the Eagles, Asylum’s first band, and his earlier triumph managing Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, Geffen proposed another would-be supergroup by lobbying John David Souther, Chris Hillman and Richie Furay to join forces. With prior band bona fides, songwriting experience and their own shared affinity for country-rock, the trio seemed poised to cash in on California’s ’70s rock gold rush.

If SHF was pitched as a trio of equals, Geffen’s first consideration was Souther, already signed to an Asylum solo deal and writing songs with the Eagles, led by his former Longbranch Pennywhistle partner, Glenn Frey. “Souther Hillman Furay was David Geffen’s attempt to make me mainstream in the wake of the Eagles’ success,” Souther would later tell rock historian Barney Hoskyns. “I think he thought I’d be the Neil [Young] of the group.”

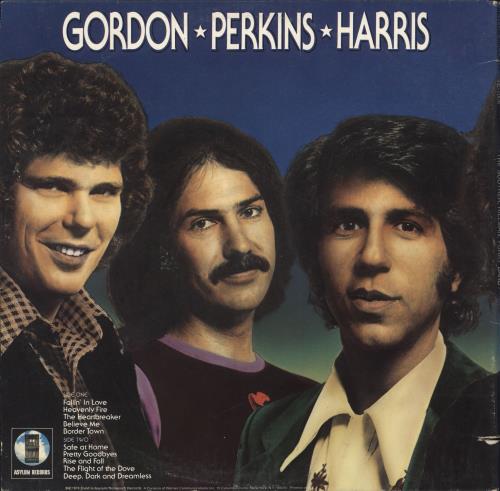

The album’s back cover

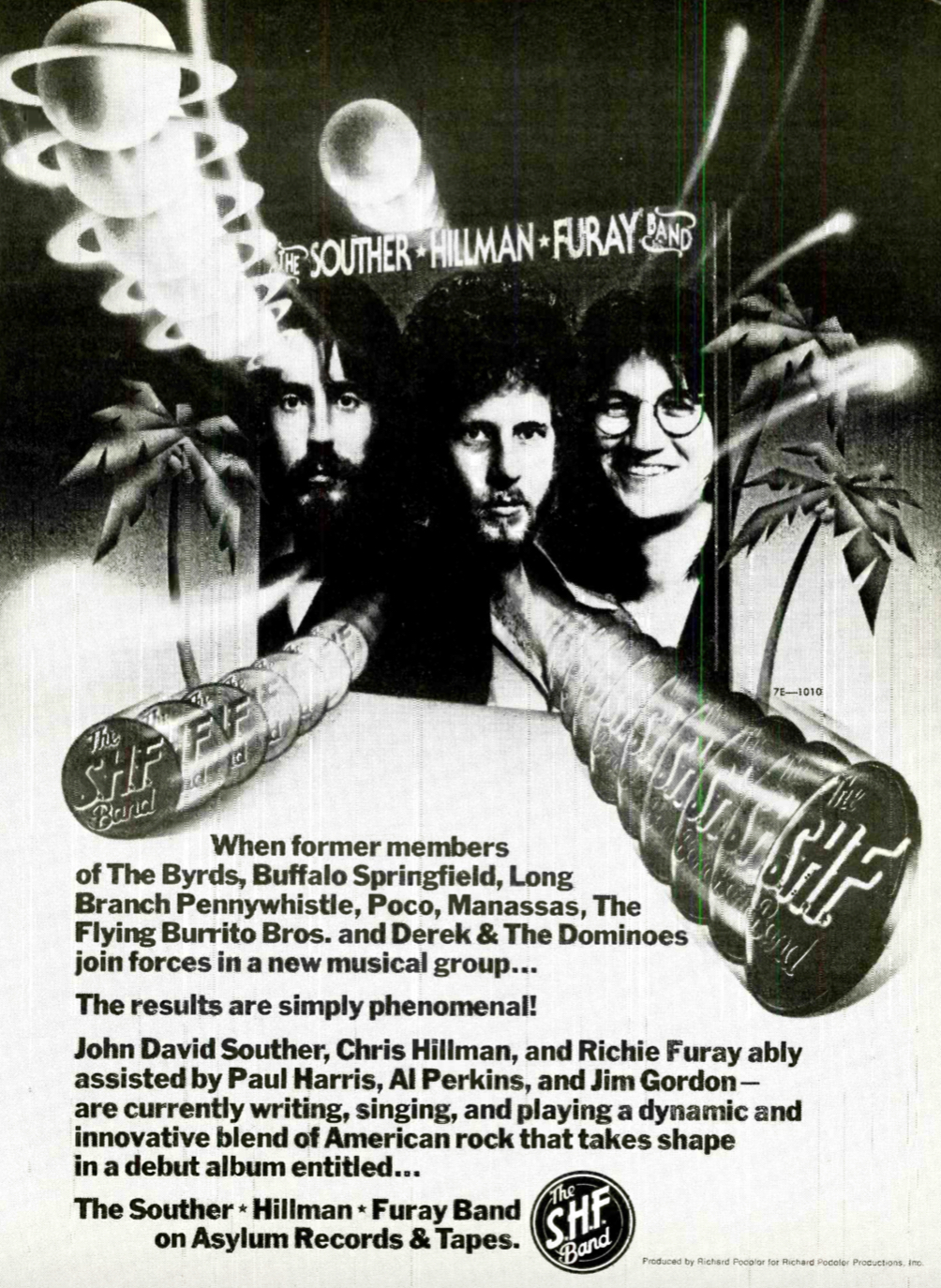

His new bandmates already enjoyed some of the luster Geffen sought for Souther. Chris Hillman had been a Byrd, a founding Burrito Brother and Stephen Stills’ wingman in Manassas. Richie Furay had followed Buffalo Springfield by co-founding Poco, one of the most influential L.A. country-rock units. To buttress that core, Hillman recruited Manassas comrades Paul Harris on keyboards and Al Perkins on pedal steel and lead guitar, along with Jim Gordon, former Derek and the Dominos drummer and a first-call studio player. Harris, Perkins and Gordon would be accorded co-billing behind the leaders in what was now the Souther Hillman Furay Band.

With visions of CSN dancing in Geffen’s head, Asylum enlisted producer Richard Podolor, who had guided Three Dog Night to an impressive streak of Top 40 single hits and gold albums. Prior bonds between Furay and Hillman, a valuable ally during Buffalo Springfield’s formation, and Manassas gave hope for a tight-knit, cohesive band, but Geffen either misread or ignored the chemistry between his three marquee names. Hillman and Furay were accustomed to collaboration, but Souther was perceived as an arrogant, acerbic maverick.

Related: Read our interview with Richie Furay

Tension was most toxic between Souther and Furay, whose friendship with born-again guitarist Perkins catalyzed Furay’s evangelical fervor, prompting Souther and Hillman to forge their own “Heathen Defense League” only partly in jest. “Richie and I were just oil and water,” Souther would later note. “I’m not a great team player under those circumstances.

Chris Hillman would be more diplomatic. “Rather than collaborating, we each brought our own songs to the table, and everyone’s material had his own personal signature attached,” he recalls in his memoir, Time Between: My Life as a Byrd, Burrito Brother, and Beyond. That assessment would be borne out in the three principals’ musical temperaments. Souther’s worldly cool contrasted sharply with Furay’s earnest intensity, with middleman Hillman laid-back yet less mannered than Souther.

Country-rock was their common denominator, but The Souther Hillman Furay Band leads off with Richie Furay’s “Fallin’ in Love,” a spirited mainstream rocker propelled by Gordon’s muscular drumming, Harris’ surging organ fills and Perkins’ sharp electric lead guitar riffs. A typically jubilant Furay vocal shares the same energy and vaulting melodic shape as “A Good Feelin’ to Know,” his best-known Poco track, which powered “Fallin’ in Love” into the Top 40, peaking at # 27.

Country accents do shape Hillman’s first vocal feature, “Heavenly Fire,” an elegy to his Burrito comrade Gram Parsons, who had died in September ’73, remembered here as a fallen comrade “who lived the life you sang about.” Perkins’ mournful pedal steel, Harris’ keyboards, and Hillman’s mandolin honor the country-rock vision for which Parsons was already being canonized, but Hillman’s pensive vocal is nearly swamped by elaborate, lapidary backing harmonies on the final choruses.

J.D. Souther, meanwhile, proves the most prolific contributor, penning four of the album’s 10 tracks. “The Heartbreaker” is a loping, R&B-edged shuffle warning against a romantic predator with “a song and a suitcase, and a rodeo smile—just a picture of style” who seduces his prey with “that magic sound.” The song showcases the Detroit-born Texan’s laconic drawl and a laid-back, jaded sensibility shared with his pals in the Eagles, evoking life in the same fast lane they would map on Hotel California. Its third-person vantage point masks the irony in Souther’s own notoriety as a ladies’ man since his early days hanging at the Troubadour’s bar, with Linda Ronstadt, Judee Sill and Stevie Nicks among his conquests.

On “Border Town,” Souther glamorizes decadence in the first person to survey the perils in a Mexican border town, citing “the dope and the night life…no place you’d really want to hang around,” before admitting, “But…I think I might.” Latin percussion buoys the track as Souther offers a roguish commentary on “good-looking women, most of them easy” and “dudes” that are “pretty greasy.” What may have passed as a cinematic tableau in 1974 now sounds tone-deaf in its casual misogyny and ethnic stereotyping.

Throughout the album, Souther’s worldly cool offers a stark contrast to Furay’s earnest intensity, while Hillman emerges as middleman both musically and temperamentally. Sandwiched between Souther’s two rockers, Furay’s “Believe Me” is a forthright romantic ballad decorated with keening pedal steel and piano arpeggios before flexing more electric firepower courtesy of Perkins’ lead electric guitar. His third SHF contribution, “The Flight of the Dove,” is a minor-keyed, mid-tempo rocker that hints at a crisis of faith that may or may not be merely romantic in origin.

Hillman splits his remaining originals between “Safe at Home,” a strutting mid-tempo rocker enlivened by Perkins’ slashing guitar leads and Gordon’s splashing cymbal crashes, and the lysergic bluegrass of “Rise and Fall.” “Safe at Home” is another cautionary tale of wretched excess from alcohol to cocaine to faithless women, tailored for ’70s rock radio, while “Rise and Fall” points to Hillman’s future embrace of acoustic country and bluegrass.

For his remaining tracks, Souther pivots to his softer side and stronger suit as a writer. “Pretty Goodbyes” is a languid waltz with elegant lyrics and a lush choral arrangement. A better balladeer than a belter, Souther’s tender vocal and the track’s musical bloom cushion the blow in what’s essentially a kiss-off to his lover, admitting he’s been “lonelier with you than I was without.” On the album closer, “Dark, Deep and Dreamless,” Souther scales up to a grandiose ballad that adds an Eagles nest of contrapuntal backing vocals around an ascending melody that reaches for, but doesn’t quite achieve, Roy Orbison’s altitude, leaving a finale that stumbles toward bombast.

Related: Remembering the prolific keyboardist Paul Harris who died in 2023

This ad for the album appeared in the July 20, 1974 issue of Record World

True to Geffen’s agenda, The Souther Hillman Furay Band, released in July 1974, accomplished its commercial mission and displayed the stylistic DNA of the Byrds, Poco and, yes, the Eagles, reaching #11 on the Billboard album chart and attaining gold status. Yet ultimately the SHF Band proved to be less than the sum of its parts, any cohesion frayed by internal friction. The antipathy between Souther and a now devout Furay only intensified, while Gordon’s increasingly volatile behavior led to his departure, a precursor to mental illness that would lead to his psychotic break in 1983 and the murder of his own mother. They would complete a second album with new drummer Ron Grinel, the aptly titled Trouble in Paradise, which met with critical and commercial indifference, hastening the group’s dissolution.

[The album is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Related: Jim Gordon, From A-List Drummer to Convicted Killer

5 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationKind of “on your way back down” I always thought.

Just the fact that each of these guys was available and willing to be put together as a band of misfit parts by David Geffen shows a bit of desperation on their parts. That’s not how great music works.

I see the writer’s point and, in some ways, i agree…that said i think it was less about JD ( who was and is one of the finest songwriters the genre produced) and more about the chemistry. Clearly there was never a problem working with the late Glenn Frey, Jackson Browne, or any number of other SoCal musicians. I like Richie Furay but the downfall of this band was the inability of him to accept JD for who is,was and work cooperatively within a band format…there,were several other good choices besides Furay including Ned Doheny, Terence Boylan ( both Asylum artists) or even Ry Cooder who would have been most useful in several areas. For proof check out the solo work of each member…Richie did a nice job on I’ve Got A Reason but the rest of his catalog is spotty at best…I like most of Chris Hillman’s solo work (in particular Slippin Away) but the cream of crop is JD’s solo output…

Richie finally got the commercial breakthrough that he so wanted but never got with Poco, though it was brief. He’s effectively said before that it really bothered him that Stills and Young moved on from Springfield with huge success, then Messina moved on from Poco and ALSO found huge success. Songwriting just wasn’t his strong suit though. In fact, his only top 40 solo hit, “I Still Have Dreams”, he didn’t even write.

Chris Hillman should’ve stuck with Manassas assuming that Manassas continued which it didn’t but that was a great band much better than SHF for sure. Too bad they called it quits so early. They had unlimited talent.