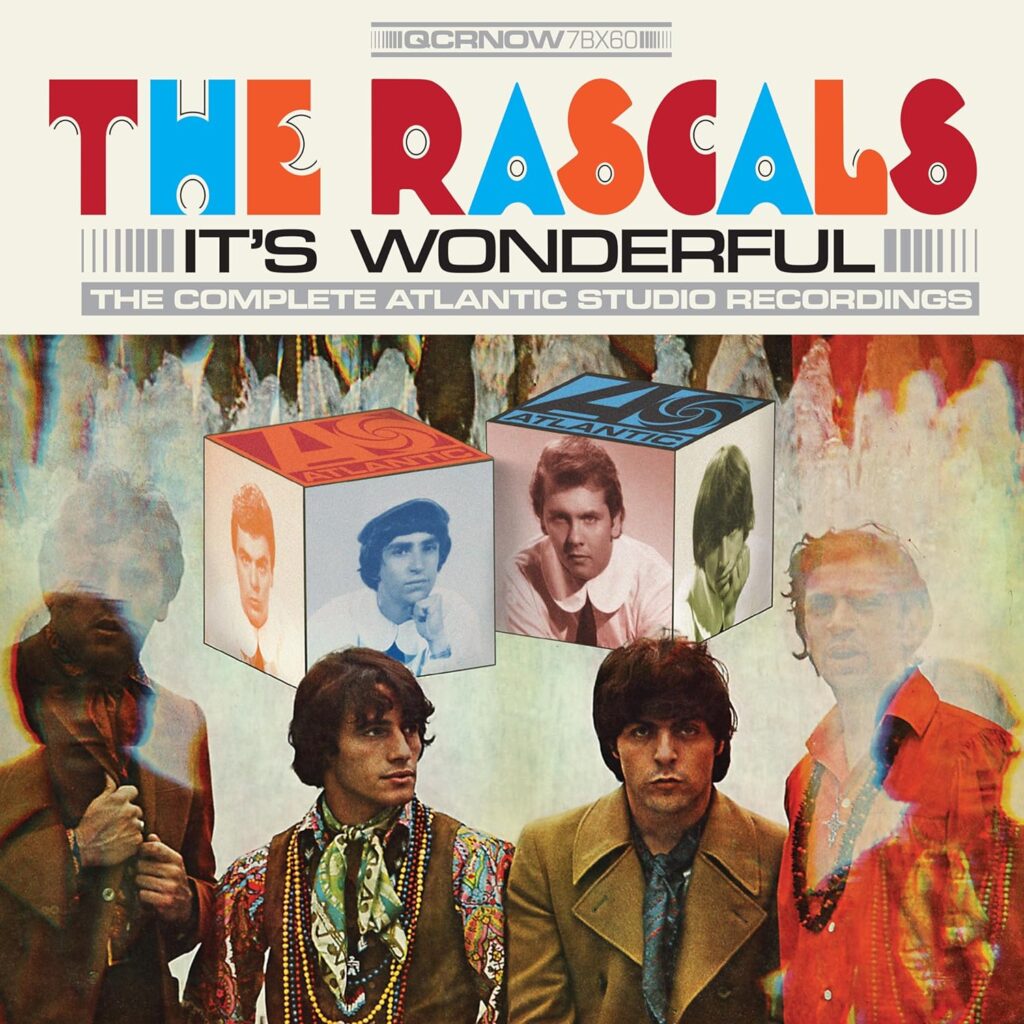

The Rascals’ entire Atlantic Records catalog, spanning 1965-1971, was re-released on May 31, 2024 on Now Sounds via the U.K.’s Cherry Red Records, as a 7-CD boxed set. The Rascals: It’s Wonderful—The Complete Atlantic Studio Recordings features 152 remastered songs, with 14 of those being previously unreleased tracks. The quartet’s first four albums are presented in both stereo and mono, included with edited singles and foreign language versions. The compilation has a 60-page booklet, detailed notes and rare illustrations from the Rascals’ archives. It’s available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

The Rascals’ entire Atlantic Records catalog, spanning 1965-1971, was re-released on May 31, 2024 on Now Sounds via the U.K.’s Cherry Red Records, as a 7-CD boxed set. The Rascals: It’s Wonderful—The Complete Atlantic Studio Recordings features 152 remastered songs, with 14 of those being previously unreleased tracks. The quartet’s first four albums are presented in both stereo and mono, included with edited singles and foreign language versions. The compilation has a 60-page booklet, detailed notes and rare illustrations from the Rascals’ archives. It’s available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

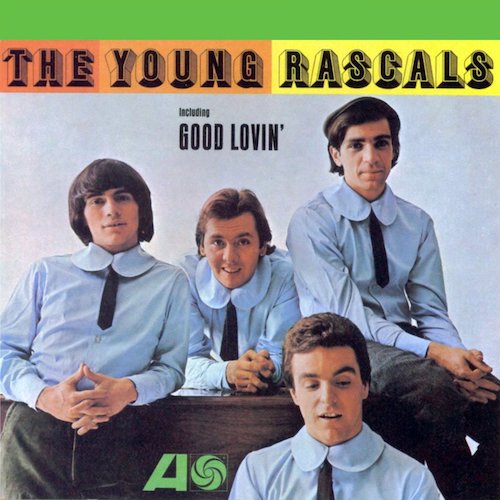

At a time dominated by the rock acts of the British Invasion, The Rascals (originally called the Young Rascals) not only survived but thrived. The post-twist New York, New Jersey and Long Island club scenes bred the band, an outfit whose sound grew more sophisticated as time went on but stayed rooted in blue-eyed soul.

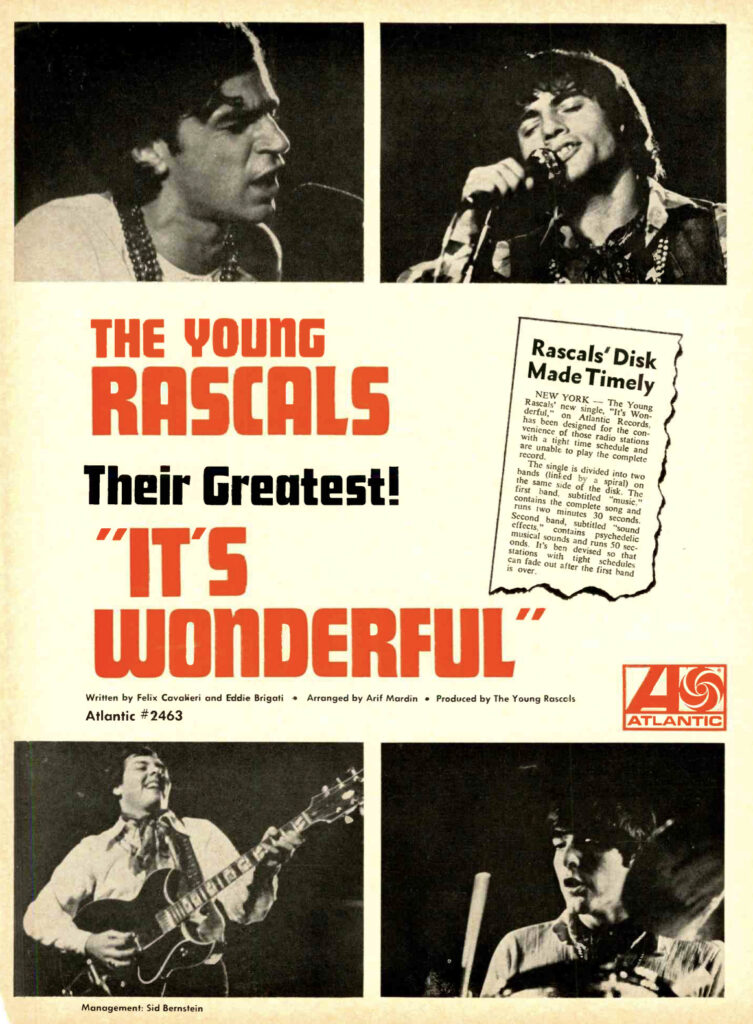

The Rascals released numerous top 10 singles in the mid- and late-1960s, including “How Can I Be Sure,” “Come on Up,” “You Better Run,” “I’ve Been Lonely Too Long,” “A Beautiful Morning” and the #1 hits “Good Lovin’,” “Groovin'” and “People Got to Be Free.”

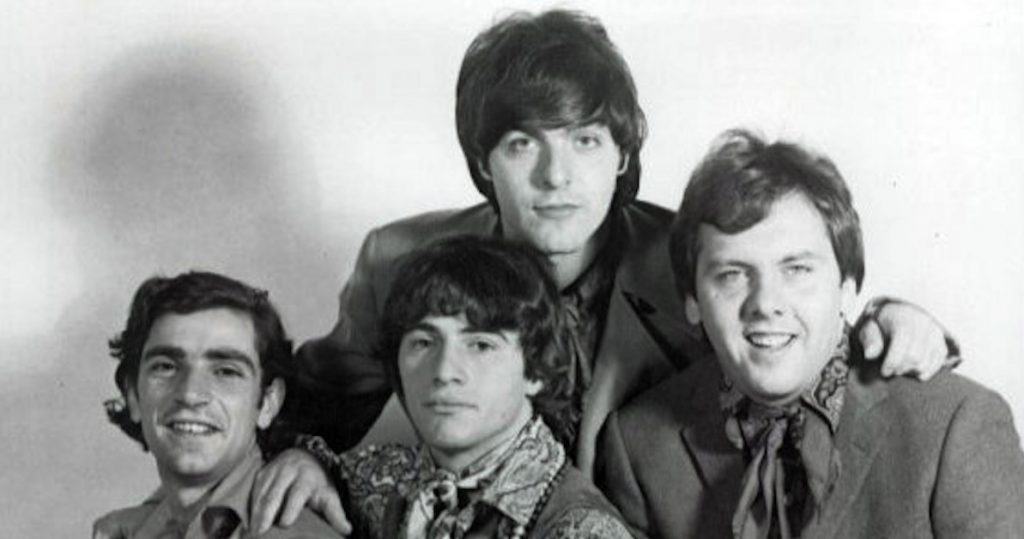

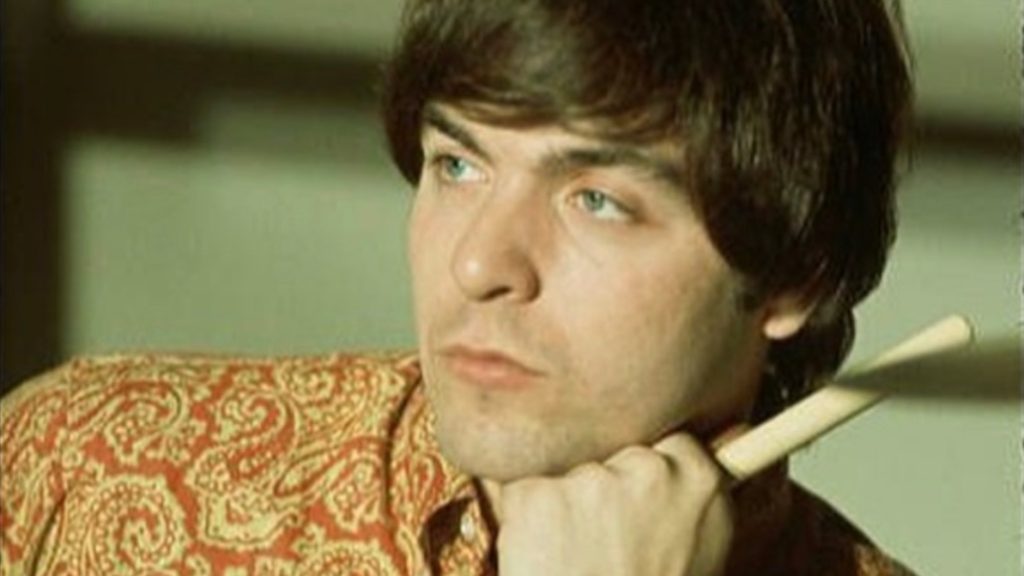

During 2013, I interviewed the four members of the Rascals. Felix Cavaliere (keyboardist/vocalist), Gene Cornish (guitar), Eddie Brigati (vocals) and Dino Danelli (drums) were touring in their hybrid rock ’n’ roll concert and Broadway show, Once Upon a Dream, which starred the Rascals, produced by Steven and Maureen Van Zandt and Marc Brickman. (Sadly, Danelli passed away in December 2022.)

“Their music was unique,” said Steven Van Zandt at the time. “Not only in its greatness but through their hit singles; it told the entire story of the ’60s. The rock and soul of the band’s beginnings to the Brill Building, folk-rock, the Civil Rights movement, jazz-rock, the psychedelic era and Vietnam—all expressed in their fantastic records. There was the blue-eyed soulful singing of their two extraordinary lead singers. Their place in history is also unique. They were one of the first [white rock] bands to demand there be Black opening acts, and of course, ‘People Got to Be Free’ is one of the anthems of the civil rights movement.”

The Rascals in their own words…

Gene Cornish: The Rascals were musicians and showmen. We danced all over the place. The Rascals were not just about love and peace. They were about civil rights, family and R&B music, a lot of substantial reasons for a band to make music. Our catalog of music is so deep. We had the blessing of Felix Cavaliere and Eddie Brigati writing our hits.

We had something unique. Felix, Eddie and I were in in the backup band for Joey Dee and the Starliters [of “Peppermint Twist” fame]. Then we took it our own way. Early on, along with the Stones and the Animals, we were projecting other music to white kids that they weren’t listening to. We had a hand in exposing that music and we owed a great debt of gratitude to R&B music.

We got [signed to] Atlantic Records, which was at the time a Black-oriented and jazz label. They said to us, “We will let you produce yourselves.” We knew what we wanted. We were given two “referees,” [producers] Tom Dowd and Arif Mardin, two adult supervisors. But they gave us a free hand. Dowd was a genius with sound. Arif was basically a young man who was hired to be the house arranger. If someone needed an arrangement for strings and horns, he was there. He would guide us, and be our “baby George Martin.”

At Atlantic, both Otis Redding and Wilson Pickett came in the studio and asked us to write songs and be the rhythm section. Then it grew and Arif became our co-producer. His first hit record he ever worked on was “Good Lovin’” with us. We cherished him tremendously. I’m the guitarist and on the first five singles I played the bass also. The last thing I did was the bass-oriented solo on “I’ve Been Lonely Too Long.”

When it came to “Groovin’,” it began as a demo. We had some studio time. We recorded the track but there was no guitar, no organ or drums on it. Dino played congas. I played the tambourine and later on the harmonica on the stereo version. Felix played the piano. Steve Cropper [of Booker T. and the MG’s] got a copy of the acetate and sat down with his group, “My God, this is a great record!” He knew it was a hit. “Let’s record this today but we can’t release it.” They held it in the can for two years and then it came out. It was about sharing.

Basically, when I did a solo on a Rascals record it was never thought out. It was never rehearsed. Either it’s tragic or magic. We cut our tracks live. Those songs give me chills today, because of the craftsmanship. And all four of us had a lot of input. It wasn’t just lyrics and melody. The feel. The emotion. Those songs came from experiences we had together. I’ve always said the Rascals were a family. Our records were our children. And those children grew up really well.

Eddie is the spirit of the Rascals. Felix is the rock. He’s the voice and Eddie is the other voice. And Dino. A drummer’s drummer.

Dino Danelli: Our songs are still on the radio, soundtracks and movies. I can‘t explain the magic of the music, but there was a chord that struck and connected our music with people, the common person. Our music is very joyous. No heavy angst or anything. It’s all very positive and you leave the show really feeling better than you did when you came in. When we played live, I always looked at myself as a front man behind the drums. I just perform like I’m the lead singer.

I am playing in a band where the Hammond B-3 organ is a principal instrument. I remember the first time I heard [their first hit] “I Ain’t Gonna Eat Out My Heart Anymore.” There was no demo. We met the girls who wrote it [Pam Sawyer and Laurie Burton] in Atlantic Studio A. At that point nobody was writing tunes; we were doing all covers. Ahmet [Ertegun] had seen us and he knew “Good Lovin’” was gonna be a smash hit. We did it differently than the Olympics. It was a whole different trip. When he heard us do it and saw the response whenever we played that song, the dance floor got crowded in three seconds and it was full with people going crazy. Ahmet didn’t want to release it first. He was a very smart guy. But it established us as a real good performing and playing band, and it really spread out all over the country that we were one of the most visually exciting bands that was coming around in rock ’n’ roll in those days. And then Ahmet knew he had a song in his back pocket and put it out and overnight “Good Lovin’” shot right up and put us on the map.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Time Peace, the first Rascals hits collection

In the Rascals, everyone left me alone and, luckily enough, I came up with different things that always fit and always enhanced. I was always conscious of working with singers and always wanted to embellish what they were doing, to hear their interpretation and try and make it better.

In those days, forget about technology. It was really primitive. But Tommy Dowd was a great musician, a great pianist, had great ears, as did Arif. And they were very smart to let our mistakes be left in. If we ever did anything that was raw and powerful but sloppy, they didn’t care. They went for the heart of it. That was really smart on their end.

In those days, forget about technology. It was really primitive. But Tommy Dowd was a great musician, a great pianist, had great ears, as did Arif. And they were very smart to let our mistakes be left in. If we ever did anything that was raw and powerful but sloppy, they didn’t care. They went for the heart of it. That was really smart on their end.

Like on “You Better Run,” the way that became a shuffle on the chorus was because of a mistake that I made. I slipped off the pedal and you hear that thing in the beginning of the record. That was a foot falling off the pedal. That’s how that came in. Tommy heard it and said, “What happened?” I said, “I’m sorry. Let’s do that again.” “No! That sounded great, Dino” So I kept doing that and it became the part in the record. And then when it came to the chorus I just felt like going into this shuffle kind of rhythm. Felix wrote it in a straight march tempo. I changed it and everybody jumped all over it. Felix came right in on top of me and Gene and it just went there. Tommy said, “Don’t worry about making mistakes.’”

We were raw and very passionate about our individual musicianship. And we were all excellent. I’m not hesitant about saying it.

Watch the Rascals perform “I’ve Been Lonely Too Long” on The Ed Sullivan Show

Eddie Bragati: We were four diverse individuals with the intention to bring life together through music and cooperation. You gotta remember, [the] Vietnam [War] was the whole schism of divide and conquer. That’s what creates wars. The religions, the flags pretending to be unifying—that’s the essence and it doesn’t go deep.

I was the youngest member. What we were lacking from the onset was true management. Music direction. Being treated properly. And the music supersedes that, young people having a good time being all-inclusive.

About the longevity of the music, I knew the music would last. Not to sound corny, because people are too jaded now, but it’s divine intervention. It’s bigger than our smugness, It’s bigger than our egos. It’s the oneness, Baba Ram Dass, Be Here Now. Buddhist. Jesus. These are all rebels but at the same time they were proponents of cooperation, of keeping together or being together. And it wasn’t only freedom of religion. It was freedom from religion. I appeal to God constantly. And she’s upset with us. It’s that oneness that stops you from bickering and analyzing and measuring. We’re not different. We’re the same and that’s when the joy comes from us.

As for the writing factor, Felix had the incentive. I created the lyrics in this way. I said, “Felix, what does this tell you in a word? Or in a sentence? What do you want this to say? Where do you want this to go?” It only worked one way. I offered lyrics a lot of times and they were never really worked on. I stood around while it was being developed. I influenced it. Dino gave us 19 different versions of heartbeats for the songs. Gene was a lead player and a rhythm player. He picked up the bass lines. No two Rascals songs are alike.

Felix Cavaliere: Hearing the Beatles…To me it was, “I could do this.” I wanted to get the best guys I could find, the best singers and musicians. And it worked. From inception to record deal was six months. That’s unheard of. Ahmet courted us. So did Phil Spector. Seriously, I wanted to produce the group ourselves. That was the goal. I didn’t want anybody to take hold of this. The freedom was there. We had unlimited studio time. And our second record, ‘Good Lovin’,” was number one.

There is a different kind of pecking order once you have a big hit. All of a sudden they have to listen to you a little bit more. It was interesting and a bit premature. In those days the only way you could work in a club was if you did other people’s songs. There was no way in New Jersey or New York you were gonna go in there and play originals. They’d throw you out on your heels. That was it. It was my job, our job, to come up with songs that were on the radio. And we had to fight for some of them, like “Mustang Sally.” They never heard that. But they were on the Black radio stations and we’d bring them to the gig. What a place to test songs. When we played “Good Lovin’,” people got up and danced. So you kind of knew instantly what could be a hit record, if in fact it ever got to that level. You could see it and hear it. We had to follow that with a million-seller. That’s not easy. So I really put my foot down, “Damn it. We’re gonna write now. No more bringing outside stuff in.”

Watch the young Rascals perform “Good Lovin'” on The Ed Sullivan Show

Initially when we were presented with “I Ain’t Gonna Eat Out My Heart Anymore,” I kind of had a crazy reaction to the songwriters coming in ’cause I wanted to write our own. But we hadn’t gotten to that point yet where we could start demanding stuff. They had a nice soulful thing and were Motown writers. “Hey, I’m a kid. Let me learn here and take it to the next step.” I wanted to do our own thing and from the beginning that was my plan. It was Beatles-stimulated. No question about it. All those English groups really opened the door for us and everybody.

As far as the Hammond B-3, when I saw an organist playing and singing, he was doing bass, rhythm, lead, vocal. I said, “This is really encompassing a whole part of the music spectrum.” One of the beauties of the Hammond is that it fills in the sonority area where the voices are. So, when you have singers and Hammond there is a blend. It really fills a room with this beautiful sound. That’s what turned me on, the overall orchestration of the instruments. The Rascals had studio bassists on the albums, jazz session men, like the Doors, who employed a bass player on their albums.

I would write the song, the title and the chorus on every one of those songs. Eddie and I were living together for a brief time on 79th Street in New York City. We had a little piano there and I would play them for him and give him an idea of what we were talking about. I genuinely felt that his verse lyrics were better than my verse lyrics. They were more colorful. I was a little bit more serious. I would get into the spirit or the politics of things.

We had a tough time. Then with “I’ve Been Lonely Too Long” and “Groovin’,” at that point in my life I fell in love and I found a muse. It was just gaga land. I was gone. All of those love songs were about this one particular person. The culmination was “How Can I Be Sure.” And then it was over. Things happen for a reason and the reason was to write those songs. That is what she was there for. The stories were genuinely about being in love.

There’s a certain divine thing that happens in every group. Gene just fit. Initially he wasn’t funky but he learned. Dino was a wild-horse drummer. I didn’t have my recording chops together but Tom [Dowd] did. We overplayed, like all young kids, and learned to chill. Atlantic Records was not a corporate entity. The studios were open to anyone. One day Otis Redding stuck his head in and said, “My God! They are white,” which I loved. That was cool.

Watch the reunited Rascals perform “Good Lovin'” at the Tony Awards in 2013

Author and music journalist Harvey Kubernik’s books are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.